Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya ...

Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya ...

Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

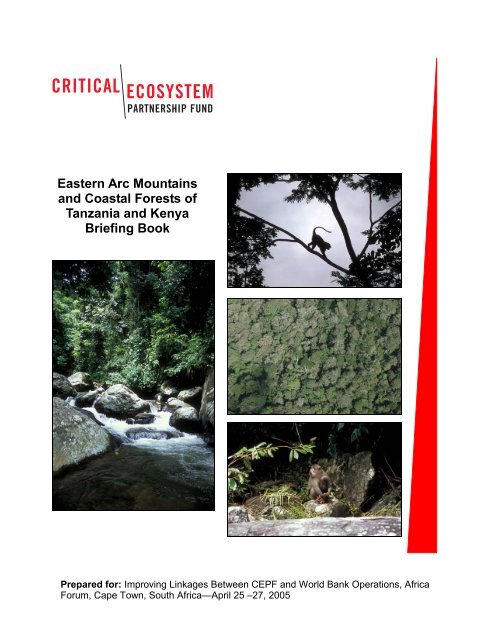

<strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>Briefing BookPrepared for: Improving Linkages Between CEPF <strong>and</strong> World Bank Operations, AfricaForum, Cape Town, South Africa—April 25 –27, 2005

EASTERN ARC MOUNTAINS AND COASTAL FORESTSOF TANZANIA AND KENYABRIEFING BOOKTable <strong>of</strong> ContentsI. The Investment Plan• Ecosystem Pr<strong>of</strong>ile Fact Sheet• Ecosystem Pr<strong>of</strong>ileII. Implementation• Overview <strong>of</strong> CEPF’s Portfolio in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>o Charts <strong>of</strong> Portfolioo Conservation Outcomes Map• Project Map• List <strong>of</strong> grantsIII. Conservation Highlights• E-News• Other HighlightsIV. Leveraging CEPF Investments• Table <strong>of</strong> Leveraged Funds

CEPF FACT SHEET<strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong><strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>CEPF INVESTMENT PLANNED IN REGION$7 millionQUICK FACTSIn <strong>Tanzania</strong>, water flowing from the <strong>Eastern</strong><strong>Arc</strong> forests is the source <strong>of</strong> 90 percent <strong>of</strong> thecountry's hydroelectric power. The forests arealso the source <strong>of</strong> water for major cities.While the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> forests once coveredmore than 23,000 square kilometers in both<strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, more recent estimatesplace the remaining forest cover as low as2,000 square kilometers.Five monkey species <strong>and</strong> at least fourspecies <strong>of</strong> prosimian primates are unique, orendemic, to this region. Found only along theTana River in <strong>Kenya</strong>, the Tana River redcolobus is Critically Endangered. Only1,000-1,200 <strong>of</strong> the Critically EndangeredZanzibar red colobus remain in the wild.The region is home to 20 out <strong>of</strong> 21 species <strong>of</strong>the African violet, which form the basis <strong>of</strong> aglobal houseplant trade.The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>region runs along the coasts <strong>of</strong> these two East African countries <strong>and</strong> includesZanzibar.The region has two distinct habitats - the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong><strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>. Together, they harbor at least 1,500 plant species foundnowhere else, as well as unique mammals, birds, reptiles <strong>and</strong> amphibians.There are 333 globally threatened species, including the Critically EndangeredAders’ duiker (Cephalophus adersi) <strong>and</strong> the Endangered Zanzibar orKirk’s red colobus (Procolobus kirkii), found only in Zanzibar’s Jozani Forest.Previously classified as a biodiversity hotspot itself, the region now lies withintwo hotspots—the <strong>Eastern</strong> Afromontane Hotspot <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Eastern</strong> Africa Hotspot—identified as part <strong>of</strong> a hotspots reappraisal released in2005. Hotspots are Earth’s biologically richest places. They hold especiallyhigh numbers <strong>of</strong> species found nowhere else <strong>and</strong> face extreme threats: Eachhotspot has already lost at least 70 percent <strong>of</strong> its original natural vegetation.THREATSThe habitats are notably fragmented, making threatened species within keysites highly vulnerable to extinction <strong>and</strong> further habitat loss. Agriculturalencroachment, timber extraction <strong>and</strong> charcoal production are the greatestthreats to habitat in this region, although weak management capacity withingovernment <strong>and</strong> communities is a serious issue.The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> comprise a chain<strong>of</strong> 12 mountain blocks stretching some 900kilometers from <strong>Tanzania</strong> to <strong>Kenya</strong>.The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Kenya</strong> region runs along the<strong>Tanzania</strong>n <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>n coasts <strong>and</strong>includes Zanzibar.1919 M STREET, NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036, USA. 1.202.912.1808 FAX 1.202.912.1045 Updated March 2005www.cepf.net

CEPF STRATEGYWithin the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong>, the CriticalEcosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) aims to improve knowledge <strong>and</strong>appreciation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity among the local populations <strong>and</strong> stimulatesupport for conservation. In conjunction with this, a commitment to scientificbest practices will improve biological knowledge in the region <strong>and</strong> showpractical applications <strong>of</strong> conservation science.The strategy is underpinned by conservation outcomes—targets against whichthe success <strong>of</strong> investments can be measured. These targets are defined at threelevels: species (extinctions avoided), sites (areas protected) <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes(biodiversity conservation corridors created).As a result, CEPF investment is focused on conserving the region’s 333globally threatened species, which are primarily found in 160 sites. Inaddition, key parts <strong>of</strong> the strategy focus on five select sites for maximumimpact (see strategic directions below). The strategy also includes a specialfocus on the linkages between people <strong>and</strong> biodiversity conservation.The five-year strategy, called an ecosystem pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong> approved by the CEPFDonor Council in 2003, builds on the results <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> studies <strong>and</strong>workshops with diverse stakeholders. CEPF began awarding grants in thisregion in 2004 <strong>and</strong>, together with partners, is now actively managing <strong>and</strong>exp<strong>and</strong>ing its investment portfolio.STRATEGIC FUNDING DIRECTIONSCEPF investments in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> areguided by five strategic directions <strong>and</strong> related investment priorities that wereagreed upon at a stakeholders meeting in March 2003. Each project must belinked to one <strong>of</strong> the strategic directions to be approved for funding:1. Increase the ability <strong>of</strong> local populations to benefit from <strong>and</strong> contributeto biodiversity conservation, especially in <strong>and</strong> around Lower Tana River<strong>Forests</strong>; Taita Hills; East Usambaras/Tanga; Udzungwas; <strong>and</strong>Jozani Forest2. Restore <strong>and</strong> increase connectivity among fragmented forest patches,especially in Lower Tana River <strong>Forests</strong>; Taita Hills; EastUsambaras/Tanga; <strong>and</strong> Udzungwas3. Improve biological knowledge (all 160 sites eligible)4. Establish a small grants program (all 160 sites eligible) that focuses onCritically Endangered species <strong>and</strong> small-scale efforts to increase connectivity<strong>of</strong> biologically important habitat patches5. Develop <strong>and</strong> support efforts for further fundraisingABOUT USCEPF is a joint initiative <strong>of</strong> ConservationInternational (CI), the Global EnvironmentFacility, the Government <strong>of</strong> Japan, the JohnD. <strong>and</strong> Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation<strong>and</strong> the World Bank. CI acts as the administrativepartner.CEPF provides strategic assistance tonongovernmental organizations, communitygroups <strong>and</strong> other civil society partners tohelp safeguard biodiversity hotspots—thebiologically richest <strong>and</strong> most threatenedareas on Earth. A fundamental goal is toensure civil society is engaged in conservingthe hotspots.In the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong><strong>Forests</strong> region, a coordination unit <strong>of</strong> fourorganizations guides CEPF investments <strong>and</strong>works directly with stakeholders to ensure aneffective, efficient <strong>and</strong> coordinated approachto achieve the outcomes.The groups are the BirdLife International-Africa Secretariat, the International Centrefor Insect Physiology <strong>and</strong> Ecology, the<strong>Tanzania</strong> Forest Conservation Group <strong>and</strong> theWWF East African Regional ProgrammeOffice. In <strong>Kenya</strong>, the BirdLife Partner isNature <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> in <strong>Tanzania</strong>, the WildlifeConservation Society <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>.HOW TO LEARN MOREFor more information about CEPF, thestrategy for this region <strong>and</strong> how to apply forgrants, visit www.cepf.net.1919 M STREET, NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036, USA. 1.202.912.1808 FAX 1.202.912.1045 Updated March 2005www.cepf.net

ECOSYSTEM PROFILEEASTERN ARC MOUNTAINS &COASTAL FORESTS OF TANZANIA & KENYAFinal versionJuly 31, 2003(updated: march 2005)

Prepared by:Conservation InternationalInternational Centre <strong>of</strong> Insect Physiology <strong>and</strong> EcologyIn collaboration with:Nature <strong>Kenya</strong>Wildlife Conservation Society <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>With the technical support <strong>of</strong>:Centre for Applied Biodiversity Science - Conservation InternationalEast African HerbariumNational Museums <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>Missouri Botanical Garden<strong>Tanzania</strong> Forest Conservation GroupZoology Department, University <strong>of</strong> Dar es SalaamWWF <strong>Eastern</strong> Africa Regional Programme OfficeWWF United StatesAnd a special team for this ecosystem pr<strong>of</strong>ile:Neil BurgessTom ButynskiIan GordonQuentin LukePeter SumbiJohn WatkinAssisted by experts <strong>and</strong> contributors:KENYABarrow EdmundGakahu ChrisGithitho AnthonyKabii TomKabugi HewsonKanga ErustusMatiku PaulMbora DavidMugo RobinsonNdugire NaftaliOdhiambo PeterThompson HazellW<strong>and</strong>ago BenTANZANIABaldus Rolf DBhukoli AliceDoggart NikeHowlett DavidHewawasam InduHamdan Sheha IdrissaHowell KimKajuni A RKilahama FelicianKafumu George RKimbwereza Elly DLejora Inyasi A.V.Lul<strong>and</strong>ala LutherMallya FelixMariki StephenMasayanyika SammyMathias LemaMilledge SimonMlowe EdwardMpemba ErastpMsuya CharlesMungaya EliasMwasumbi LeonardSalehe JohnStodsrod Jan ErikTapper ElizabethOffninga EstherPerkin AndrewVerberkmoes Anne MarieWard JessicaBELGIUMLens LucUKBurgess NeilUSABrooks ThomasGereau RoyLanghammer PennyOcker DonnellSebunya KadduStruhsaker TomWieczkowski JulieEditing assistance by Ian Gordon, International Centre <strong>of</strong> Insect Physiology <strong>and</strong> Ecologyii

CONTENTSINTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................................................................5THE ECOSYSTEM PROFILE............................................................................................................................................5BACKGROUND......................................................................................................................................................................6Geography <strong>of</strong> the Hotspot.........................................................................................7The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> ......................................................................................8The East African <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic ................................................................10BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE........................................................................................................................................11Biodiversity in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> ..............................................................11Biodiversity in the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> .........................................................................12Levels <strong>of</strong> Protection ................................................................................................13CONSERVATION OUTCOMES ...................................................................................................................................16Overview <strong>of</strong> Conservation Outcomes .....................................................................17Species Outcomes..................................................................................................18Site Outcomes ........................................................................................................19SOCIOECONOMIC FEATURES ..................................................................................................................................25Institutional Framework...........................................................................................25Policy <strong>and</strong> Legislation.............................................................................................29Economic Situation.................................................................................................34Infrastructure <strong>and</strong> Regional Development ..............................................................36Demography <strong>and</strong> Social Trends .............................................................................37SYNOPSIS OF CURRENT THREATS.......................................................................................................................38Levels <strong>of</strong> Threat......................................................................................................39Main Threats...........................................................................................................39Agriculture...............................................................................................................40Commercial Timber Extraction ...............................................................................42Mining .....................................................................................................................43Fires........................................................................................................................43Ranking <strong>of</strong> Threats in <strong>Tanzania</strong>..............................................................................44Analysis <strong>of</strong> Root Causes.........................................................................................45SYNOPSIS OF CURRENT INVESTMENT...............................................................................................................48Levels <strong>of</strong> Funding ...................................................................................................48Types <strong>of</strong> Project Interventions ................................................................................49Numbers <strong>of</strong> IBAs with Project Interventions ...........................................................49Spread <strong>of</strong> Conservation Attention Across Different IBAs........................................50Funding Allocation Against Biological Priority.........................................................50CEPF NICHE FOR INVESTMENT................................................................................................................................52CEPF INVESTMENT STRATEGY AND PRIORITIES..........................................................................................54Program Focus .......................................................................................................54Strategic Directions.................................................................................................54SUSTAINABILITY ...............................................................................................................................................................62CONCLUSION......................................................................................................................................................................63ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE TEXT....................................................................................................................64REFERENCES.....................................................................................................................................................................66APPENDICES.......................................................................................................................................................................71iv

INTRODUCTIONThe Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is designed to safeguard the world's threatenedbiodiversity hotspots in developing countries. It is a joint initiative <strong>of</strong> Conservation International(CI), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Government <strong>of</strong> Japan, the MacArthurFoundation <strong>and</strong> the World Bank. CEPF supports projects in hotspots, the biologically richest <strong>and</strong>most endangered areas on Earth.A fundamental purpose <strong>of</strong> CEPF is to ensure that civil society is engaged in efforts to conservebiodiversity in the hotspots. An additional purpose is to ensure that those efforts complementexisting strategies <strong>and</strong> frameworks established by local, regional <strong>and</strong> national governments.CEPF aims to promote working alliances among community groups, nongovernmentalorganizations (NGOs), government, academic institutions <strong>and</strong> the private sector, combiningunique capacities <strong>and</strong> eliminating duplication <strong>of</strong> efforts for a comprehensive approach toconservation. CEPF is unique among funding mechanisms in that it focuses on biological areasrather than political boundaries <strong>and</strong> examines conservation threats on a corridor-wide basis toidentify <strong>and</strong> support a regional, rather than a national, approach to achieving conservationoutcomes. Corridors are determined through a process <strong>of</strong> identifying important species, site <strong>and</strong>corridor-level conservation outcomes for the hotspot. CEPF targets transboundary cooperationwhen areas rich in biological value straddle national borders, or in areas where a regionalapproach will be more effective than a national approach.The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> hotspot (hereafterreferred to as the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspot) is one <strong>of</strong> the smallest <strong>of</strong>the 25 global biodiversity hotspots. 1 It qualifies by virtue <strong>of</strong> its high endemicity <strong>and</strong> a severedegree <strong>of</strong> threat. Although the hotspot ranks low compared to other hotspots in total numbers <strong>of</strong>endemic species, it ranks first among the 25 hotspots in the number <strong>of</strong> endemic plant <strong>and</strong>vertebrate species per unit area (Myers et al. 2000). It also shows a high degree <strong>of</strong> congruencefor plants <strong>and</strong> vertebrates. It is also considered as the hotspot most likely to suffer the most plant<strong>and</strong> vertebrate extinction for a given loss <strong>of</strong> habitat <strong>and</strong> as one <strong>of</strong> 11 “hyperhot” priorities forconservation investment (Brooks et al. 2002).THE ECOSYSTEM PROFILEThe purpose <strong>of</strong> the ecosystem pr<strong>of</strong>ile is to provide an overview <strong>of</strong> biodiversity values,conservation targets or “outcomes,” the causes <strong>of</strong> biodiversity loss <strong>and</strong> current conservationinvestments in a particular hotspot. Its purpose is to identify the niche where CEPF investmentscan provide the greatest incremental value.The ecosystem pr<strong>of</strong>ile recommends strategic opportunities, called “strategic funding directions.”Civil society organizations then propose projects <strong>and</strong> actions that fit into these strategicdirections <strong>and</strong> contribute to the conservation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity in the hotspot. Applicants proposespecific projects consistent with these funding directions <strong>and</strong> investment criteria. The ecosystempr<strong>of</strong>ile does not define the specific activities that prospective implementers may propose, butoutlines the conservation strategy that guides those activities. Applicants for CEPF grants arerequired to prepare detailed proposals identifying <strong>and</strong> describing the interventions <strong>and</strong>performance indicators that will be used to evaluate the success <strong>of</strong> the project.1 At the time this document was prepared in 2003, the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> region wasclassified as a biodiversity hotspot itself. However, a hotspots reappraisal released in 2005 places this region withintwo new hotspots - the <strong>Eastern</strong> Afromontane Hotspot <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eastern</strong> Africa Hotspot. Thispr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong> CEPF investments focus strictly on the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> comprising theoriginal hotspot as defined in this document.5

BACKGROUNDInternational interest in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspot has increasedover the last three decades as the realization <strong>of</strong> its biodiversity importance <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> the globalcrisis affecting tropical forests has deepened. Although descriptions <strong>of</strong> the wealth <strong>of</strong> biodiversityin the forests <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> date back to 1860 <strong>and</strong> there has been outst<strong>and</strong>ingscientific work in the hotspot during the last 100 years, concerns for its conservation arerelatively recent. Until about 30 years ago, nearly all the investment in the forests <strong>of</strong> the area hadbeen in plantations, many <strong>of</strong> which were established after clearing indigenous forest.The situation is now greatly changed <strong>and</strong> the last decade has seen a series <strong>of</strong> publications,workshops <strong>and</strong> conferences on the biodiversity <strong>and</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> this hotspot (mostlyorganized by the United Nations Development Programme/Global Environment Facility(UNDP/GEF) <strong>and</strong> the WWF <strong>Eastern</strong> Africa Regional Programme Office (WWF-EARPO).These have produced a wealth <strong>of</strong> recent information on biodiversity issues (in particular on thedistribution <strong>of</strong> endemic species across sites) <strong>and</strong> on forest status <strong>and</strong> management. Thisinformation has greatly reduced the time <strong>and</strong> effort needed to prepare this pr<strong>of</strong>ile.Current concerns for the conservation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> date back to the 1978Fourth East African Wildlife Symposium at Arusha. The conference was attended by 150delegates, most <strong>of</strong> whom were not especially interested in forest conservation. However, a postconferencetrip to Amani in the East Usambaras resulted in a report to the Government <strong>of</strong><strong>Tanzania</strong>, drawing its attention to the biological importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong> threats to the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong><strong>Mountains</strong> (Rodgers 1998).In 1983, the <strong>Tanzania</strong> Forest Conservation Group (TFCG) was founded. In December 1997,there was a l<strong>and</strong>mark international conference on the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> at Morogoro,<strong>Tanzania</strong> attended by more than 250 delegates (Burgess et al. 1998a). During this conference,working groups reported on urgent issues such as the status <strong>of</strong> the remaining forest <strong>and</strong>participants presented papers on biodiversity, sociology <strong>and</strong> management. Much <strong>of</strong> the morerecent conservation effort in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> dates from this conference, although one<strong>of</strong> the most important <strong>of</strong> these had already started with a UNDP/DANIDA project. This led inturn to a GEF Project Development Fund (PDF) Block A proposal <strong>and</strong> grant to characterize theconservation issues in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> in more detail.The Block A process started after the December 1997 conference <strong>and</strong> included preliminaryassessments <strong>of</strong> biodiversity values, conservation concerns, priority actions, financial constraints,sustainable financing opportunities, effectiveness <strong>of</strong> previous donor interventions <strong>and</strong> thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> preliminary proposals for GEF projects in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>. A threewaymatrix was constructed showing levels <strong>of</strong> biodiversity <strong>and</strong> endemism, the degree <strong>of</strong> threat<strong>and</strong> the level <strong>and</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> previous interventions. This enabled a ranking exercise thatrevealed that three <strong>of</strong> the main forest blocks (East Usambaras, Udzungwas <strong>and</strong> Ulugurus) wereexceptionally diverse <strong>and</strong> that there was no major donor or public support for the Ulugurus. TheUlugurus, therefore, became a focus in the development <strong>of</strong> a PDF Block B proposal supportedby UNDP <strong>and</strong> the World Bank. This PDF/B involved extensive stakeholder consultations <strong>and</strong>resulted in: 1) an outline <strong>and</strong> plan for a participatory <strong>and</strong> strategic approach to conservation <strong>and</strong>management in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>; 2) proposals for institutional reforms in the forestsector with a particular focus on facilitating participatory forest conservation <strong>and</strong> management;3) a needs assessment for priority pilot interventions in the Ulugurus; <strong>and</strong> 4) the legalestablishment <strong>of</strong> an <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> Endowment Fund (EAMCEF). The outcomes fromthis process were integrated into larger forest biodiversity concerns <strong>and</strong> into a proposed $62.2million <strong>Tanzania</strong> Forest Conservation <strong>and</strong> Management Project.6

During this time, awareness <strong>of</strong> the biodiversity values <strong>of</strong> the East African coastal forests hadalso grown. In 1983, a team from the International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP, nowBirdLife International) surveyed the avifauna <strong>of</strong> Arabuko-Sokoke Forest on the north coast <strong>of</strong><strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> drew attention to its globally threatened bird species (Kelsey & Langton, 1984). Adetailed survey (Roberston, 1987) <strong>of</strong> the sacred Kaya <strong>Forests</strong> (conserved by the Mijikenda, agroup <strong>of</strong> nine tribes on the <strong>Kenya</strong>n coast) highlighted their conservation importance for trees<strong>and</strong> led to a comprehensive survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>n coastal forests commissioned by WWF(Robertson & Luke 1993). This focussed on the plant species <strong>and</strong> on the status <strong>of</strong> the forests <strong>and</strong>made recommendations for their conservation.The Frontier-<strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Research Programme carried out a series <strong>of</strong> biodiversitysurveys from 1989 to 1994 (Lowe & Clarke 2000; Clarke et al. 2000; Burgess et al. 2000;Broadley & Howell, 2000; H<strong>of</strong>fman 2000). In 1993 a workshop on the East African coastalforests was held in Dar es Salaam. This raised the pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong> conservation action in these forests<strong>and</strong> led to a series <strong>of</strong> status reports on the conservation <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Tanzania</strong>ncoastal forests (Clarke 1995; Clarke & Dickenson 1995; Clarke & Stubblefield 1995). These <strong>and</strong>other studies are summarized in another l<strong>and</strong>mark publication for the hotspot (Burgess &Clarke, 2000).More recently, WWF-EARPO organised a series <strong>of</strong> workshops to develop an <strong>Eastern</strong> Africa<strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Programme covering <strong>Kenya</strong>, <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mozambique (WWF-EARPO, 2002).Thirty-one scientists <strong>and</strong> stakeholders from these three countries attended a regional workshopin Nairobi in February 2002. It aimed at developing a regional synthesis on coastal forestresource issues <strong>and</strong> a vision, strategy <strong>and</strong> way forward for realising the coastal forestprogramme. There was a strong focus on country-based group work. Maps <strong>of</strong> the region wereupdated, threats <strong>and</strong> root causes were analyzed, country conservation targets were agreed on <strong>and</strong>preliminary logframe action plans were developed for each country. National <strong>Coastal</strong> ForestTask Force meetings in each <strong>of</strong> the three countries subsequently refined these action plans. Thedocument resulting from the February 2002 workshop includes comprehensive annexes whichlist the coastal forest sites (showing their locations, areas, status, altitudes <strong>and</strong> threats) <strong>and</strong> theendemic animals, as well as the threat analysis <strong>and</strong> country action plans. A list <strong>of</strong> endemicplants, taken from Burgess & Clarke 2000, was supplied to the workshop but not included in thereport.On 12 March 2003, a CEPF workshop was held in Dar es Salaam to define the investment nichefor CEPF, building on all the previous effort. Participants included 48 people from scientific <strong>and</strong>research institutions, government departments, NGOs, field projects <strong>and</strong> donor organizations, all<strong>of</strong> whom worked in or had knowledge <strong>of</strong> the hotspot. The outputs from the workshop weresubsequently incorporated into a wide-ranging consultation process that helped to define theinvestment priorities for CEPF in this hotspot.Geography <strong>of</strong> the HotspotThe <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspot runs along the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>ncoasts from the border with Somalia to the north to that with Mozambique to the south (Figure1). The bulk <strong>of</strong> the hotspot is in its western expansion in <strong>Tanzania</strong>, which takes in the <strong>Eastern</strong><strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> the water catchment system <strong>of</strong> the Rufiji River. There is a narrow hook-likeextension <strong>of</strong> the hotspot near the <strong>Kenya</strong>/<strong>Tanzania</strong> border. This follows the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong><strong>Mountains</strong> to their northernmost limits in the Taita Hills in <strong>Kenya</strong>. The hotspot also projectsnorthwards for about 100 km in an extension that includes the forests <strong>of</strong> the Lower Tana Riverin <strong>Kenya</strong>. The hotspot includes the Indian Ocean isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Mafia, Pemba <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar.7

In terms <strong>of</strong> plant biogeography, the hotspot straddles two ecoregions: <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> Forest <strong>and</strong>Northern Zanzibar-Inhambane <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic (WWF-US 2003a, b). These twoecoregions are mostly discontinuous but do meet in the lowl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the East Usambara,Uluguru, Nguru <strong>and</strong> Udzungwa <strong>Mountains</strong> as well as in the Mahenge Plateau (WWF-US2003a,b; Burgess pers. com.). A considerable proportion <strong>of</strong> species (e.g. nearly 60 percent <strong>of</strong>plants) are found in both ecoregions <strong>and</strong> the distinction between them has been a matter <strong>of</strong> somedebate (Lovett et al. 2000). However, each <strong>of</strong> these forest types contains an impressive number<strong>of</strong> strict endemics. Lovett et al. (2000) conclude that the forests in these two ecoregions are verydifferent, with differences in altitude <strong>and</strong> rainfall leading to a steep gradient <strong>of</strong> speciesreplacement with elevation.The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>The <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> stretch for some 900 km from the Makambako Gap, southwest <strong>of</strong>the Udzungwa <strong>Mountains</strong> in southern <strong>Tanzania</strong> to the Taita Hills in south-coastal <strong>Kenya</strong> (Figure2) (Lovett & Wasser 1993; GEF 2002). They comprise a chain <strong>of</strong> 12 main mountain blocks:from south to north, Mahenge, Udzungwa, Rubeho, Uluguru, Ukaguru, North <strong>and</strong> South Nguru,Nguu, East Usambara, West Usambara, North Pare, South Pare <strong>and</strong> Taita Hills. The highestpoint (Kimh<strong>and</strong>u Peak in the Ulugurus) is more than 2,600 m in altitude, but most <strong>of</strong> the rangespeak between 2,200-2,500 m (GEF 2002; WWF-US 2003a). Geologically the mountains areformed mainly from Pre-Cambrian basement rocks uplifted about 100 million years ago(Griffiths 1993). Their proximity to the Indian Ocean ensures high rainfall (3,000 mm/ year onthe eastern slopes <strong>of</strong> the Ulugurus, falling to 600 mm/year in the western rain shadow) (GEF2002). Climatic conditions are believed to have been more-or-less stable for at least the past 30million years (Axelrod & Raven 1978). The high rainfall <strong>and</strong> long-term climatic stability,together with the fragmentation <strong>of</strong> the mountain blocks, have resulted in forests that are bothancient <strong>and</strong> biologically diverse.The original forest cover (2,000 years ago) on the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> is estimated at around23,000 km 2 , <strong>of</strong> which around 15,000 km 2 remained by 1900 <strong>and</strong> a maximum <strong>of</strong> 5,340 km 2remained by the mid-1990s (Newmark 1998; GEF 2002). At that time the Udzungwas containedthe largest area <strong>of</strong> natural forest (1,960 km 2 ), followed by the Nguru, Uluguru, Rubeho, EastUsambaras, South Pare, West Usambaras, Mahenge, Ukaguru, North Pare <strong>and</strong> Taita Hills (6km 2 ). These <strong>and</strong> the following estimates <strong>of</strong> forest status <strong>and</strong> losses in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong>8

Figure 1. Location <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> & <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspot9

<strong>Mountains</strong> are all taken from Newmark 1998. Losses were greatest, relative to original cover, inthe Taitas (98 percent), Ukaguru (90 percent), Mahenge (89 percent) <strong>and</strong> West Usambaras (84percent). The forests had become highly fragmented, with mean <strong>and</strong> median forest patch sizesestimated at 10 km 2 <strong>and</strong> 58 km 2 , respectively. By 1994-96, the Udzungwas <strong>and</strong> the WestUsambaras contained the largest numbers <strong>of</strong> patches (26 <strong>and</strong> 17) <strong>and</strong> only one mountain block(Ukaguru) had more or less continuous forest. At that time there were an estimated 94 forestpatches in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>. Within forest patches there was considerable degradation.Of the closed forest that remained, only 27 percent had closed forest cover. With the exception<strong>of</strong> a few sites where there has been active intervention, the situation at present is far more likelyto have deteriorated than improved since 1996.The East African <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest MosaicThe area defined by the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> in the hotspot includes theintervening habitats between the coastal forest patches. Although the main biodiversity valuesare concentrated in the forests there are a significant number <strong>of</strong> endemics (especially plants) innon-forested habitats. This part <strong>of</strong> the hotspot is therefore a mosaic, which stretches from theborder <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> with Somalia, to the border <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> with Mozambique, including theisl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Zanzibar, Mafia <strong>and</strong> Pemba. This part <strong>of</strong> the hotspot is, largely for practical reasons,partly defined by national boundaries; coastal forests in Somalia (very little left) <strong>and</strong>Mozambique (large areas) are poorly known <strong>and</strong> are excluded. Northern Mozambique could beincluded with further survey work. With the exception <strong>of</strong> Somalia, the mosaic, as defined here,corresponds to the WWF ecoregion known as the “Northern Zanzibar-Inhambane <strong>Coastal</strong> ForestMosaic” (WWF-US 2003b). This falls within the “Zanzibar-Inhambane Regional Mosaic,”which is one <strong>of</strong> 18 distinct biogeographical regions that White (1983) recognized for Africa.In <strong>Kenya</strong>, the Northern Zanzibar-Inhambane <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic is mostly confined to anarrow coastal strip except along the Tana River where it extends inl<strong>and</strong> to include the forests <strong>of</strong>the lower Tana River (the northern-most <strong>of</strong> which occur within the Tana Primate NationalReserve) (Figures 1, 2). In <strong>Tanzania</strong>, the Mosaic runs from border to border along the coast,contracting in the Rufiji Delta region. There are also some outliers located up to ca. 300 kminl<strong>and</strong> at the base <strong>of</strong> a few <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> (Udzungwa, Mahenge, Uluguru <strong>and</strong>Nguru) (WWF-US 2003a). Much <strong>of</strong> the Mosaic has been converted to subsistence agriculture,interrupted by plantations <strong>and</strong> human settlements, including the large cities <strong>of</strong> Mombasa <strong>and</strong> Dares Salaam (populations <strong>of</strong> more than 700,000 <strong>and</strong> 3 million, respectively).Geologically, the coastal forest strip has been subject to considerable tectonic activity <strong>and</strong> tosedimentation <strong>and</strong> erosion associated with movements <strong>of</strong> the shoreline (Clarke & Burgess 2000).Most coastal forests are found between 0-50 m <strong>and</strong> 300-500 m, although in <strong>Tanzania</strong> they occurup to 1040 m (Burgess et al. 2000). Rainfall ranges between 2000 mm/year (Pemba) to 500mm/year (northern <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> southern <strong>Tanzania</strong>) (Clarke 2000). There are two rainy seasons(long, April-June; short, November-December) in the north, but only one (April-June) in thesouth. Dry seasons can be severe <strong>and</strong> El Niño effects dramatic. Climatic conditions are believedto have been relatively stable for the last 30 million years (Axelrod & Raven 1978), althoughvariation from year to year can be considerable, leading to droughts or floods.By the early 1990s, there were about 175 forest patches in the <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic (<strong>Kenya</strong> 95,<strong>Tanzania</strong> 66) covering an area <strong>of</strong> 1,360 km 2 (<strong>Kenya</strong> 660 km 2 , <strong>Tanzania</strong> 700 km 2 ) (Burgess et al.2000). Mean patch size was 6.7 km 2 in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> 10.6 km 2 in <strong>Tanzania</strong>. Modal patch-sizeclasses were 0 – 1 km 2 in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> 5-15 km 2 in <strong>Tanzania</strong>. The two largest coastal forests areboth in <strong>Kenya</strong> (Arabuko-Sokoke, minimum area 370 km 2 ; Shimba, minimum area 63 km 2 )(WWF-EARPO 2002), while in <strong>Tanzania</strong> there are no coastal forests larger than 40 km 2 (WWF-US 2003b). There is some uncertainty with these figures because <strong>of</strong> differences in criteria for10

patch inclusion in the data set (e.g., the exclusion <strong>of</strong> all but a few small patches (

The degree <strong>of</strong> faunal endemism in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> varies widely across taxa. Sixpercent <strong>of</strong> mammals, 3 percent <strong>of</strong> birds, 68 percent <strong>of</strong> forest-dependent reptiles, 63 percent <strong>of</strong>forest-dependent amphibians, 39 percent <strong>of</strong> butterflies <strong>and</strong> 82 percent <strong>of</strong> linyphiid spiders areendemic (GEF 2002). Some <strong>of</strong> these species have extremely limited distributions. The Kihansispray toad, described in 1998, is found in an area <strong>of</strong> less than 1 km 2 (Poynton et al. 1998). Threeendemic bird taxa (variously described as full species or subspecies) are restricted to the 6 km 2<strong>of</strong> forest in the Taita Hills (Brooks et al. 1998). Records for the Udzungwa partridge areconfined to two localities in the Udzungwas <strong>and</strong> one in Rubeho (Baker & Baker 2002). Amongstsome invertebrates (linyphiid spiders, opilionids <strong>and</strong> carabid beetles), single site endemismexceeds 80 percent (Scharff et al. 1981; Scharff 1992, 1993; Burgess et al. 1998).Using a subset <strong>of</strong> 239 species endemic <strong>and</strong> near-endemic to the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>, the EastUsambaras emerge as the most important site in terms <strong>of</strong> numbers <strong>of</strong> endemics, while theUlugurus rank top for density <strong>of</strong> endemics (Burgess et al. 2001). As expected, the big forestblocks (Usambaras, Ulugurus <strong>and</strong> Udzungwas) are more species-rich than the smaller blocks(e.g., North Pare, South Pare, Ukaguru <strong>and</strong> Mahenge). Most <strong>of</strong> the endemic taxa are not onlyforest dependent; they are dependent on primary forest. The low-elevation forests are rich inendemics <strong>and</strong> total numbers <strong>of</strong> species, but are very limited in overall area, having sufferedextensive clearance for agriculture. The uniqueness <strong>of</strong> the biodiversity in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong><strong>Mountains</strong> is attributable to both relictual <strong>and</strong> recently evolved species (Burgess et al. 1998c;Roy et al. 1997). Biogeographical affinities indicate ancient connections to Madagascar (45species <strong>of</strong> bryophytes shared) (Pocs 1998), West Africa (many birds <strong>and</strong> plant genera) (Lovett1998b; Burgess et al. 1998c) <strong>and</strong> even Southeast Asia (where close relatives <strong>of</strong> the Udzungwaforest partridge <strong>and</strong> the African tailorbird are found) (Dinesen et al. 1994).Biodiversity in the <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong>The pattern <strong>of</strong> endemism in the <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic is complex, reflecting the wide range <strong>of</strong>habitats <strong>and</strong> heterogeneous forest types, a high degree <strong>of</strong> turnover <strong>of</strong> local species betweenadjacent forest patches <strong>and</strong> many disjunct distributions (Burgess 2000; WWF-US 2003b). Theecoregion, which includes the isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Zanzibar <strong>and</strong> Pemba, is a mosaic <strong>of</strong> forest patches,savanna woodl<strong>and</strong>s, bushl<strong>and</strong>s, thickets <strong>and</strong> farml<strong>and</strong>. The highest biodiversity is found in thevarious kinds <strong>of</strong> closed canopy forest vegetation: dry forest, scrub forest, Brachystegia(miombo) forest, riverine forest, groundwater forest, swamp forest <strong>and</strong> coastal/afromontanetransition forest (Clarke 2000; WWF-US 2003b). Closed canopy forests, however, makes uponly 1 percent <strong>of</strong> the total area <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Coastal</strong> Forest Mosaic.Overall, there are more than 4,500 plant species <strong>and</strong> 1,050 plant genera (WWF-US 2003b), witharound 3,000 species <strong>and</strong> 750 genera occurring in forest. At least 400 plant species are endemicto the forest patches <strong>and</strong> about another 500 are endemic to the intervening habitats that make up99 percent <strong>of</strong> the ecoregion area (WWF-US 2003b). The majority <strong>of</strong> these species are woody butthere are also endemic climbers, shrubs, herbs, grasses <strong>and</strong> sedges (Clarke et al. 2000). Asubstantial proportion <strong>of</strong> the endemic plants are confined to a single forest (for example, RondoForest, <strong>Tanzania</strong>, has 60 strict endemics <strong>and</strong> Shimba Hills, <strong>Kenya</strong>, has 12) (Clarke et al. 2000).The flora as a whole has affinities with that <strong>of</strong> West Africa, suggesting an ancient connectionwith the Guineo-Congolian lowl<strong>and</strong> forests (Lovett 1993). Endemism is primarily relictualrather than recently evolved (Clarke et al. 2000; Burgess et al. 1998c).Faunal endemism rates have been estimated for forest species in the Swahelian Regional Centre<strong>of</strong> Endemism (including the transition zone in Mozambique). These are highest in theinvertebrate groups such as millipedes (80 percent <strong>of</strong> all the forest species), molluscs (68percent) <strong>and</strong> forest butterflies (19 percent) (Burgess 2000). Amongst the vertebrates, 7 percent<strong>of</strong> forest mammals, 10 percent <strong>of</strong> forest birds, 57 percent <strong>of</strong> forest reptiles <strong>and</strong> 36 percent <strong>of</strong>12

forest amphibians are endemic (Burgess 2000). If Mozambique is excluded, endemics include14 species <strong>of</strong> birds (including four on Pemba Isl<strong>and</strong>), eight mammals, 36 reptiles <strong>and</strong> fiveamphibians (WWF-EARPO 2002).In terms <strong>of</strong> species richness, there are at least 158 species <strong>of</strong> mammals (17 percent <strong>of</strong> allAfrotropical species), 94 reptiles <strong>and</strong> 1200 molluscs (WWF-US 2003b). As with the plants,endemism is primarily relictual (Burgess et al. 1998c) <strong>and</strong> single site endemism <strong>and</strong> disjunctdistributions are common. This makes it extremely difficult to prioritise the forests in terms <strong>of</strong>their biodiversity. Burgess (2000) made a preliminary analysis on the basis <strong>of</strong> species richness<strong>and</strong> endemism, using vascular plants, birds, mammals, reptiles <strong>and</strong> amphibians. This showedthat different forests are important for different groups. For example, while Arabuko-Sokoke istop for endemic birds <strong>and</strong> for mammal species richness, it barely makes it into the top ten forplants. Overall, the five most important forests are Rondo (plants <strong>and</strong> birds), lowl<strong>and</strong> EastUsambaras <strong>and</strong> Arabuko-Sokoke (birds, mammals <strong>and</strong> reptiles), Shimba (plants <strong>and</strong> birds) <strong>and</strong>Pugu Hills (birds <strong>and</strong> mammals). Pemba Isl<strong>and</strong>, with an area <strong>of</strong> only 101400 ha, isextraordinarily important for birds with four endemic species (Baker & Baker, 2002) whileZanzibar has six endemic mammals <strong>and</strong> three endemic birds (Siex, pers. comm.).Levels <strong>of</strong> Protection<strong>Forests</strong> in this hotspot are located in two countries <strong>and</strong> fall under multiple management regimes.Figure 2 shows the major protected areas in <strong>and</strong> around the hotspot.In <strong>Kenya</strong>, the protected area network at national level consists <strong>of</strong> national parks, nationalreserves, forest reserves, nature reserves <strong>and</strong> national monuments (Bennun & Njoroge 1999).Many <strong>of</strong> the national monuments on the coast are sacred forests called Kaya <strong>Forests</strong>. At a lowerlevel, many forests are located on trust l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> fall under the control <strong>of</strong> County <strong>and</strong> Municipalcouncils. In <strong>Tanzania</strong>, the protected area network at national level consists <strong>of</strong> national parks,game reserves, government catchment forests, game controlled areas, forest reserves <strong>and</strong> naturereserves (Baker & Baker 2002). Below the national level a large number <strong>of</strong> forests, particularlyin the coastal forest belt, fall under local authorities, owned <strong>and</strong> managed by the villagers. Inboth countries, no exploitation is allowed in national parks <strong>and</strong> protection levels are generallyhigh (but see below for an exception in <strong>Kenya</strong>). In both countries, confusing <strong>and</strong> overlappinglegislation on the environment <strong>and</strong> natural resources is being rationalized through the enactment<strong>of</strong> new polices.Within the <strong>Kenya</strong>n area <strong>of</strong> the hotspot, there is one national park, a 6 km 2 area to the northwest<strong>of</strong> Arabuko-Sokoke Forest. This park is, however, somewhat <strong>of</strong> an anomaly, as it contains noclosed forest <strong>and</strong> exists only on paper. There are four national reserves (Shimba, Tana River,Boni <strong>and</strong> Dodori) (WWF-EARPO 2002). These fall under the jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Kenya</strong> WildlifeService (KWS). The Shimba Hills were gazetted as National Forest in 1903 <strong>and</strong> then doublegazetted(with the exception <strong>of</strong> two small areas that remained as forest reserves under the control<strong>of</strong> the Forest Department) in 1968 as the Shimba Hills National Reserve (Bennun & Njoroge1999). Protection levels are higher in the area controlled by KWS, as they have armed rangers<strong>and</strong> a clearer institutional m<strong>and</strong>ate for conservation. The Tana River Primate National Reservecontains 16 out <strong>of</strong> the 70 patches <strong>of</strong> riverine forest found along the lower Tana River (Butynski& Mwangi 1994). There forests have suffered severe damage during the past three decades fromfarmers clearing l<strong>and</strong> for agriculture <strong>and</strong> possibly from the construction <strong>of</strong> several dams up-riverthat have reduced the incidence <strong>of</strong> flooding (Butynski & Mwangi 1994, Wieczkowski & Mbora1999-2000). The biodiversity in Boni <strong>and</strong> Dodori is poorly known because security problemshave prevented biological surveys.13

The largest <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Kenya</strong>n forest reserves is Arabuko Sokoke (417 km 2 ). For the last 10 yearsthis forest has been under multi-institutional management (KWS, the Forest Department, <strong>Kenya</strong>Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) <strong>and</strong> the National Museums <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, (NMK)) (Arabuko-Sokoke Forest Management Team 2002). This arrangement has been taken as a model for otherindigenous forests in <strong>Kenya</strong> but has been rarely implemented. Protection levels suffer from theproximity <strong>of</strong> the tourist resorts <strong>of</strong> Malindi <strong>and</strong> Watamu <strong>and</strong> the resultant dem<strong>and</strong> for carvingwood <strong>and</strong> timber. The effectiveness <strong>of</strong> management has been variable over time, being subject tothe commitment <strong>of</strong> the personnel on the ground, the working relationships between KWS <strong>and</strong>the Forest Department <strong>and</strong> the level <strong>of</strong> resources available. Generally, however, managementhas been more effective than in the other 17 forest reserves (WWF-EARPO 2002) within the<strong>Kenya</strong>n coastal forest belt. In the fragmented forests <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Kenya</strong>n portion <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong><strong>Mountains</strong> (Taita Hills), some patches, including plantation, have been gazetted as forestreserve. Others are on trust l<strong>and</strong> administered by the local county council, some <strong>of</strong> which havebeen recommended for gazettement as forest reserves (Bennun & Njoroge 1999).14

Figure 2. Location <strong>of</strong> the major protected areas in <strong>and</strong> around the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspotNational monument status has been given to 39 out <strong>of</strong> nearly 50 <strong>of</strong> the sacred Kaya forests(WWF-EARPO 2002), but the level <strong>of</strong> protection gained from this status is below that <strong>of</strong> theforest reserves. An additional national monument at Gede Ruins is not a Kaya, but it includes afenced 350 ha coral rag forest that is in good condition <strong>and</strong> very well protected. There arenumerous Local Government or County Council <strong>Forests</strong>. Unfortunately, protection <strong>of</strong> theseforests is virtually non-existent, to the point where local councillors have sold forest plots foragricultural settlement (e.g., at Madunguni <strong>and</strong> Mangea Hill). A large proportion (nearly 4015

percent) <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Kenya</strong>n coastal forests fall into this category or is totally unprotected (data fromWWF-EARPO 2002).In the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n portion <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong>, there are two national parks (Udzungwa<strong>Mountains</strong> National Park, gazetted in 1992, 1,960 km 2 ; <strong>and</strong> Mikumi National Park, 3,230 km 2 ),two game reserves (Selous <strong>and</strong> Mkomazi) <strong>and</strong> a nature reserve (Amani Nature Reserve, gazettedin 1997, 83.8 km 2 ) (GEF 2002; Roe et al. 2002). However, more than 90 percent <strong>of</strong> the totalforest area in the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n portion <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> almost 75 percent <strong>of</strong> thetotal forests are gazetted as government catchment forest reserves (Burgess pers. com.). Theserange in area from more than 557,000 ha (Ngindo) to less than 10 ha <strong>and</strong> include all the largerforests in the Kilimanajaro (e.g., Chome), Tanga (e.g., Nguru North, Shume Magambe) <strong>and</strong>Morogoro (e.g., Uluguru, Nguru South) regions. Most <strong>of</strong> the remainder are local authorityforests, ranging in size from 57,300 ha (Mbalwe/Mfukulembe) to less than 10 ha, although thereare a few private forests, mainly on tea estates (e.g. Ambangulu Tea Estate) <strong>and</strong> some <strong>of</strong> whichhave been covenanted for conservation. In the national park, protection levels are high, butelsewhere they are highly variable. The important catchment forest reserves are, in general,better protected than the local authority forests (Burgess et al. 1998).In the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n coastal forests, management regimes are more complicated. Most are eitherforest reserves (80) or are on public l<strong>and</strong> (20) with no protection status (WWF-EARPO 2002).Four are private forest reserves (Magotwe, Kichi Hills, Mlungui <strong>and</strong> Magoroto). Only three areentirely managed by the district government as local authority forest reserves, although somehave double status (two overlapping with forest reserves <strong>and</strong> two more with private forestreserves). There are two catchment forest reserves (Mselezi, Ziwani) (Burgess <strong>and</strong> Clarke 2000;WWF-EARPO 2002) managed by the Central Government Forest <strong>and</strong> Beekeeping Division.Two others, Zaraninge <strong>and</strong> the former Mkwaja ranch, are being incorporated into the newSadaani National Park (WWF-EARPO 2002). Some patches are also found in the Selous GameReserve <strong>and</strong> others in Mafia Isl<strong>and</strong> Marine Park. Offshore protected areas are also found inZanzibar (Jozani Forest Reserve) <strong>and</strong> Pemba (Ngezi Forest Reserve). There are also smallerareas in Zanzibar that are important for water catchment (e.g. Masingi) <strong>and</strong> for endemic species(e.g. Unguja Ukuu Forest Plantation). There is a proposal to upgrade the Jozani Reserve inZanzibar (now known as the Jozani-Chakwa Bay Conservation Area) to a national park.Management <strong>and</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the forests throughout the hotspot have suffered frominadequate stakeholder involvement, conflicts <strong>of</strong> interest <strong>and</strong> corruption. Where forests aregazetted, the boundaries tend to be respected but the forests themselves suffer steadydegradation. The levels <strong>of</strong> protection achieved on the ground are strongly dependent on localfactors such as proximity to urban areas, pressure for l<strong>and</strong>, ease <strong>of</strong> access, presence <strong>of</strong> valuabletimber <strong>and</strong> the capacity <strong>and</strong> morale <strong>of</strong> the local forestry <strong>of</strong>ficers (WWF-US 2003a). There is ageneral move toward various forms <strong>of</strong> participatory forest management (PFM), in the hope thatan exchange <strong>of</strong> forest user rights for community management responsibilities <strong>and</strong> ownership(where appropriate) will lead to better protection by the people who <strong>of</strong>ten know best what isgoing on in the forests. Although this hope is widely held, it has not yet been scientifically testedwithin the hotspot. The alternative strategies <strong>of</strong> direct payments <strong>and</strong> easements are beingexplored, but have not yet been implemented.CONSERVATION OUTCOMESThis ecosystem pr<strong>of</strong>ile, together with pr<strong>of</strong>iles under development for other regions at this time,includes a new commitment <strong>and</strong> emphasis on using conservation outcomes—targets againstwhich the success <strong>of</strong> investments can be measured—as the scientific underpinning fordetermining CEPF’s geographic <strong>and</strong> thematic focus for investment.16

Conservation outcomes are the full set <strong>of</strong> quantitative <strong>and</strong> justifiable conservation targets in ahotspot that need to be achieved in order to prevent biodiversity loss. These targets are definedat three levels: species (extinctions avoided), sites (areas protected) <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes (corridorscreated). As conservation in the field succeeds in achieving these targets, these targets becomedemonstrable results or outcomes. While CEPF cannot achieve all <strong>of</strong> the outcomes identified fora region on its own, the partnership is trying to ensure that its conservation investments areworking toward preventing biodiversity loss <strong>and</strong> that its success can be monitored <strong>and</strong>measured. CI’s Center for Applied Biodiversity Science (CABS) is facilitating the definition <strong>of</strong>conservation outcomes across the 25 global hotspots, representing the benchmarks against whichthe global conservation community can gauge the success <strong>of</strong> conservation measures.Overview <strong>of</strong> Conservation OutcomesConservation outcomes focus on biodiversity across a hierarchical continuum <strong>of</strong> ecologicalscales. This continuum can be condensed into the three levels: species, sites <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. Thethree levels interlock geographically through the presence <strong>of</strong> species in sites <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> sites inl<strong>and</strong>scapes. They are also logically connected. If species are to be conserved, the sites on whichthey live must be protected <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scapes must continue to sustain the ecological serviceson which the sites <strong>and</strong> the species depend. At the l<strong>and</strong>scape level, conservation corridors (withinwhich sites are nested) can sometimes be defined <strong>and</strong> investments can be targeted at increasingthe amount <strong>of</strong> habitat with ecological <strong>and</strong> biodiversity value within these corridors. Giventhreats to biodiversity at each <strong>of</strong> the three levels, quantifiable targets for conservation can be setin terms <strong>of</strong> extinctions avoided, sites protected <strong>and</strong>, where appropriate, conservation corridorscreated or preserved. This can only be done when accurate <strong>and</strong> comprehensive data are availableon the distribution <strong>of</strong> threatened species across sites <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes.Defining conservation outcomes is therefore a bottom-up process through which species-leveltargets are defined first <strong>and</strong> based on the species information, site-level conservation targets areidentified. L<strong>and</strong>scape-level targets are delineated subsequently, if appropriate for the region. Theprocess requires knowledge on the conservation status <strong>of</strong> individual species. This informationhas been accumulating in the Red Lists <strong>of</strong> Threatened Species developed by IUCN <strong>and</strong> partners.The Red List is based on quantitative, globally applicable criteria under which the probability <strong>of</strong>extinction is estimated for each species. Species outcomes in the hotspot include those speciesthat are globally threatened (Vulnerable, Endangered <strong>and</strong> Critically Endangered) according toThe 2002 IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened Species. Outcome definition is a fluid process <strong>and</strong>, asdata become available, species-level outcomes will be exp<strong>and</strong>ed to include other taxonomicgroups that previously had not been assessed, as well as restricted-range species. Avoidingextinctions means conserving globally threatened species to make sure that their Red List statusimproves or at least stabilizes. This in turn means that data are needed on population trends; formost <strong>of</strong> the threatened species, there are no such data.Recognizing that most species are best conserved through the protection <strong>of</strong> the sites in whichthey occur, site outcomes are defined for each target species. Site outcomes are focused onphysically <strong>and</strong>/or socioeconomically discrete areas <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> that harbour populations <strong>of</strong> at leastone globally threatened species. These sites need to be protected from ecological transformationto conserve the target species. Sites are scale-independent <strong>and</strong>, ideally, should be manageable assingle units.Corridor outcomes are focused on l<strong>and</strong>scapes that need to be conserved to allow the persistence<strong>of</strong> biodiversity over time. Species <strong>and</strong> site outcomes are nested within corridors. The goal <strong>of</strong>corridors is to preserve ecological <strong>and</strong> evolutionary processes, as well as enhance connectivitybetween important conservation sites by effectively increasing the amount <strong>of</strong> habitat withbiodiversity value near them. Unlike species <strong>and</strong> site outcomes, the criteria for determining17

corridor outcomes are being defined <strong>and</strong> this is presently an important research front. CABS willmake the data on conservation outcomes publicly available on CEPF's Web site, www.cepf.net.Species OutcomesTo define the species outcomes for this hotspot, all globally threatened species in The 2002 RedList <strong>of</strong> Threatened Species that are found in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong>hotspot were identified. Data were compiled for each species on its conservation status <strong>and</strong>known distribution. Site outcomes were determined by identifying all sites that are important foreach globally threatened species. Following a review <strong>of</strong> the species <strong>and</strong> site outcomes <strong>and</strong> expertconsultations, corridor outcomes were not defined for this hotspot. Conservation corridors(l<strong>and</strong>scape conservation units consisting <strong>of</strong> core sites <strong>and</strong> the surrounding matrix) did not makesense in this naturally fragmented, relatively small hotspot. However, it will be important toreconnect forest patches that have only become isolated in recent decades as a result <strong>of</strong> humanactivities. Failure to reconnect forest patches within a formerly continuous site will inevitablymean the extinction <strong>of</strong> numerous species as the habitat patches fall to sizes that can no longersustain their biodiversity due to isl<strong>and</strong> biogeography effects (Newmark 1991, 2002; Brooks etal. 2002).The definition <strong>of</strong> the conservation outcomes drew heavily on the research findings <strong>of</strong> a largenumber <strong>of</strong> scientists who have worked intensively in this hotspot over the last three decades <strong>and</strong>who have contributed to various compilations <strong>of</strong> primary field data (Lovett & Wasser 1993;Burgess et al. 1998, Burgess & Clarke 2000; Newmark 2002; WWF-EARPO 2002; WWF-US2003a,b). The key sources <strong>of</strong> data on threatened plants included the Flora <strong>of</strong> Tropical EastAfrica (see Beentje & Smith [2001] for details <strong>of</strong> publication), the TROPICOS database (MBG2003) <strong>and</strong> a database compiled by Q. Luke. Data on faunal species distributions in <strong>Tanzania</strong>were drawn from the University <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salaam biodiversity database (Howell & Msuya2003). The work to define national Important Bird Areas (IBAs) was also an important source <strong>of</strong>data. The IBA process in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> (coordinated by Nature <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> the WildlifeConservation Society <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> as the BirdLife International partners for these countries) hadalready compiled data for threatened <strong>and</strong> restricted-range birds <strong>and</strong> their key sites (IBAs). Thesedata were already in the World Bird Database at BirdLife International. The IBAs provided astarting point for including other aspects <strong>of</strong> the biodiversity <strong>of</strong> this hotspot to identify keybiodiversity areas, or site level conservation outcomes.The results <strong>of</strong> the outcome definition indicate that 333 globally threatened (Red List) speciesoccur in the hotspot, with 105 species being represented in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> 307 in <strong>Tanzania</strong> (Table1). The globally threatened flora <strong>and</strong> fauna in the hotspot are represented by 236 plant species,29 mammal species, 28 bird species, 33 amphibian species <strong>and</strong> seven gastropod species. Of the333 globally threatened species in the hotspot, 241 are Vulnerable, 68 are Endangered <strong>and</strong> 24are Critically Endangered.The full list <strong>of</strong> species outcomes is provided in Appendix 1. The species outcomes are based onthe 2002 IUCN Red List, which is quite good for several taxonomic groups. However, Red Listdata for plants is badly in need <strong>of</strong> updating. The 2002 Red List includes some widespread plantspecies in this hotspot, others that are in far greater danger <strong>of</strong> extinction because their restricted18

Table 1. Numbers <strong>of</strong> Critically Endangered, Endangered <strong>and</strong> Vulnerable species in five majortaxonomic groups in the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong> <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspotDegree <strong>of</strong> ThreatCountryTaxonomic Group CR EN VU Total <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>Mammals 5 8 16 29 27 9Birds 3 1028 24 1015Amphibians 4 11 18 33 31 3Gastropods 3 3 1 7 4 3Plants 9 36 191 236 221 80Total 24 68 241 333 307 105CR = Critically Endangered, EN = Endangered, VU = Vulnerableranges have not yet been assessed (Q. Luke & R. Gereau pers. comm.). Gereau <strong>and</strong> Luke (2003)estimate the total number <strong>of</strong> globally threatened plant species in the hotspot is probably 1,200 ormore, including 973 taxa that are not in the 2002 IUCN Red List <strong>and</strong> that urgently need to beassessed for degree <strong>of</strong> threat status.Noticeably absent from the species outcomes are reptiles, freshwater fish <strong>and</strong> nearly all theinvertebrates. None <strong>of</strong> the reptiles or fish within this hotspot is currently on the IUCN Red List.This is a result <strong>of</strong> either (1) a lack <strong>of</strong> information on these species or simply (2) because nobodyhas yet made the required “assessment” for possible inclusion in the Red List. Amonginvertebrates, information was only available for gastropods. It is expected that many moreinvertebrate species (as well as plants <strong>and</strong> reptiles) will prove to be threatened once they areassessed using updated IUCN criteria. A list <strong>of</strong> potentially threatened dragonflies has also beencompiled by Viola Clausnitzer <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> Marburg, Germany.Table 2 lists the 24 Critically Endangered species in this hotspot (five mammals, three birds,four amphibians, three gastropods <strong>and</strong> nine plants). Of these 24 species, 12 occur in <strong>Tanzania</strong>,seven in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> five in both <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. If extinctions are to be avoided, the full set<strong>of</strong> these Critically Endangered species, together with the sites they depend on, must be rankedhigh among any priorities for conservation action. For example, 17 <strong>of</strong> the 24 CriticallyEndangered species in this hotspot are each restricted to a single site. This result is important forthe site prioritization process.There are other species in the hotspot, currently listed as Endangered, which should be reassessedfor threat status. These include the Zanzibar red colobus monkey (Procolobus kirkii)(less than 2,000, mostly in Jozani Forest Reserve) <strong>and</strong> Aders’ duiker (probably less than 800 in avery restricted range with a 50 percent decline within last 15-20 years) (Struhsaker pers.comm.). Two other Endangered species—African Elephant <strong>and</strong> African Wild Dog—wereidentified as “l<strong>and</strong>scape species,” indicating that they will likely not be conserved through a sitebasedapproach alone.Site OutcomesThe definition <strong>of</strong> site outcomes produced 160 Key Biodiversity Areas for the <strong>Eastern</strong> <strong>Arc</strong><strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong> hotspot (Appendix 2, Table 3). Among these, 41 sites areimportant for mammals, 29 for birds, 19 for amphibians, four for gastropods <strong>and</strong> 140 for plants.In the hotspot, 26 sites are home to 10 or more globally threatened species, 53 sites have two to19

nine globally threatened species <strong>and</strong> 73 are important for at least one globally threatened speciesamong the considered taxonomic groups. Nine more sites are included in Appendix 2, notbecause they host globally threatened species, but because they are IBAs with restricted-rangebird species <strong>and</strong> globally significant congregations <strong>of</strong> birds. The full description <strong>of</strong> siteoutcomes <strong>and</strong> the species that occur in them is presented in Appendix 3. Figure 3 shows thelocation <strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> the site outcomes in <strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. The sites were overlaidwith other existing geographical information including national boundaries, protected areas,rivers <strong>and</strong> topography to show their distribution in relation to other features.Further analysis <strong>of</strong> the composition <strong>of</strong> the site outcomes (Appendix 2 <strong>and</strong> 3) indicates that 51 <strong>of</strong>the 160 sites are IBAs (Bennun & Njoroge 1999; Baker & Baker 2002). Some sites have highnumbers <strong>of</strong> threatened species. These sites include: East Usambara <strong>Mountains</strong>, Uluguru<strong>Mountains</strong>, Udzungwa <strong>Mountains</strong> National Park, West Usambara <strong>Mountains</strong>, Udzungwa<strong>Mountains</strong>, Shimba Hills, Lindi District <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong>, Nguru <strong>Mountains</strong>, Taita Hills, SouthPare <strong>Mountains</strong> <strong>and</strong> Kisarawe District <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Forests</strong>. When the sites are ranked according tothe number <strong>of</strong> threatened species that they contain, 23 <strong>of</strong> the top 25 sites are IBAs. This suggeststhat the IBA process succeeds in identifying the key sites for conserving species <strong>of</strong> globalconcern, at least on a broad scale.20