Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

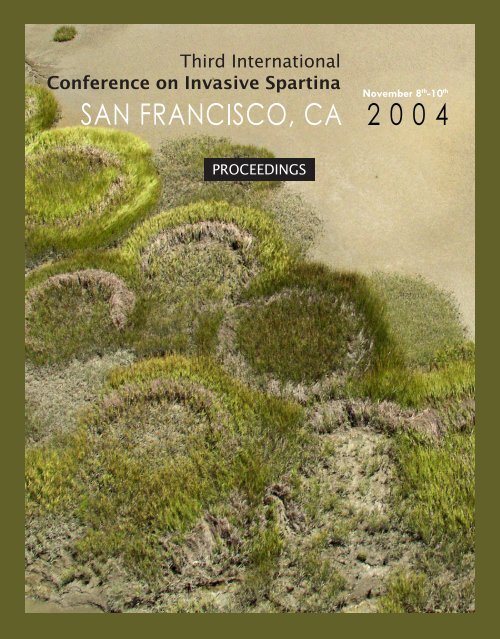

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaSAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIANovember 8-10, 2004Editors:Debra R. Ayres, Science EditorDrew W. Kerr, Management EditorStephanie D. Erics<strong>on</strong>, Copy and Layout EditorPeggy R. Ol<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<strong>on</strong>, Executive Editor2010

CONFERENCE AND PROCEEDINGS FUNDINGCalifornia State Coastal C<strong>on</strong>servancySan Francisco Bay-Delta Science C<strong>on</strong>sortium (Agreement #46000001642)University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, DavisNati<strong>on</strong>al Science Foundati<strong>on</strong>California Sea GrantSan Francisco Bay Joint VentureSan Francisco Estuary ProjectSan Francisco Estuary InstituteU.S. Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Protecti<strong>on</strong> Agency, Regi<strong>on</strong> 9Suggested Citati<strong>on</strong>:Ayres, D.R., D.W. Kerr, S.D. Erics<strong>on</strong> and P.R. Ol<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<strong>on</strong>, eds. 2010. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina, 2004 Nov 8-10, San Francisco, CA, USA. San Francisco Estuary<strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Project <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California State Coastal C<strong>on</strong>servancy: Oakland, CA.Printed <strong>on</strong> recycled paper.

FORWARD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina c<strong>on</strong>vened to provide a forum for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bestand latest Spartina research, and an opportunity to discuss new developments in Spartina science with marshland managers and technical experts who had extensive experience with this invasive genus. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>me <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference, “Linking science and management,” reflected <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> desire <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> organizers to improve bothfields through increased exposure and interacti<strong>on</strong> with each o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, c<strong>on</strong>tinuing and extending a focus <strong>on</strong>uniting managers and researchers that was established at earlier internati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>ferences <strong>on</strong> this subject. Thefirst internati<strong>on</strong>al Spartina c<strong>on</strong>ference was held in 1990 in Seattle, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sec<strong>on</strong>d in 1997 inOlympia, Washingt<strong>on</strong>. We are pleased to have hosted <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong>Spartina here in San Francisco, California in 2004.The success <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this event was <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hard work and support <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals andorganizati<strong>on</strong>s. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> Organizing Committee helped to guide <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ferenceand addressed organizati<strong>on</strong>al issues as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y arose. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> Organizing Committee included:Ms. Marcia Brockbank, Program Manager, San Francisco Estuary ProjectDr. Mike C<strong>on</strong>ner, Executive Director, San Francisco Estuary InstitutePr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Edwin Grosholz, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science and Policy, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, DavisMr. Paul Hedge, Project Manager, Nati<strong>on</strong>al Oceans Office, AustraliaMr. Doug Johns<strong>on</strong>, Executive Director, California <strong>Invasive</strong> Plants CouncilMs. Peggy Ol<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<strong>on</strong>, Director, San Francisco Estuary <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina ProjectDr. Kim Patten, Director, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach Research and Extensi<strong>on</strong> Unit, Washingt<strong>on</strong> State UniversityDr. Bobbye Smith, Regi<strong>on</strong>al Science Liais<strong>on</strong> to Office <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Research and Development, USEPA Regi<strong>on</strong> 9Ms. Erin Williams, N<strong>on</strong>-native <strong>Invasive</strong> Species Program Coordinator, U.S. Fish and Wildlife ServiceThe Science Program Committee developed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference program, selected presentati<strong>on</strong>s andspecial guest presenters, and provided support throughout <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference. The Science Program Committeeincluded:Dr. Lars Anders<strong>on</strong>, Exotic and <strong>Invasive</strong> Weed Research Laboratory, U.S. Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> AgricultureDr. Debra Ayres, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong> and Ecology, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, DavisDr. Peter Baye, San Francisco Estuary <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina ProjectMs. Janie Civille, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong> and Ecology, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, DavisDr. Joshua Collins, Wetlands Program, San Francisco Estuary InstitutePr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Edwin Grosholz, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science and Policy, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, DavisDr. Kim Patten, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach Research and Extensi<strong>on</strong> Unit, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Washingt<strong>on</strong>Dr. Drew Talley, Romberg Tibur<strong>on</strong> Center, San Francisco Bay Nati<strong>on</strong>al Estuarine Research ReserveMajor financial support for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference was provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California State CoastalC<strong>on</strong>servancy, San Francisco Bay-Delta Science C<strong>on</strong>sortium (Agreement #46000001642), and University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>California, Davis. Additi<strong>on</strong>al support for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference was provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nati<strong>on</strong>al Science Foundati<strong>on</strong>,California Sea Grant, San Francisco Bay Joint Venture, San Francisco Estuary Project, San FranciscoEstuary Institute, and U.S. Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Protecti<strong>on</strong> Agency, Regi<strong>on</strong> 9.A lunche<strong>on</strong> and exhibit <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sec<strong>on</strong>d day <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference provided an opportunity for participantsto network while learning about emerging treatment technologies. We are grateful to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> followingcompanies for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir sp<strong>on</strong>sorship <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this lunche<strong>on</strong>: Aquatic Envir<strong>on</strong>ments, Inc., BASF Corporati<strong>on</strong>, Cygneti

Enterprises West, Inc., Helena Chemical Company, M<strong>on</strong>santo Company, Nufarm Turf & Specialty, Wilbur-Ellis Company, and Wilco Industries.Producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this proceedings volume has been a l<strong>on</strong>g and fragmented process, because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sporadic availability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time and funding. We thank <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> authors for both <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir time and effort in preparing<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se excellent papers, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir patience as we worked through several years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> staff changes, competingpriorities, and funding loss. We are especially grateful to Debra Ayres, who ultimately coordinated <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> peerreview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 36 papers in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first three secti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this volume; to Drew Kerr, who reviewed and edited <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>16 papers in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last secti<strong>on</strong>; and to Stephanie Erics<strong>on</strong>, who worked countless hours for over four years toedit, organize, and layout <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> entire volume.Peggy R. Ol<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<strong>on</strong>Organizing Committee Chair andDirector, San Francisco Estuary <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Projectii

TABLE OF CONTENTSForward & Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. iIntroducti<strong>on</strong> .......................................................................................................................................... viiChapter 1: Spartina Biology ................................................................................................................ 1California Cordgrass (Spartina foliosa), an Endemic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Salt Marsh Habitats al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pacific Coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Western North AmericaM.C. Vasey ................................................................................................................................................ 3Local and Geographic Variati<strong>on</strong> in Spartina-herbivore Interacti<strong>on</strong>sS.C. Pennings ............................................................................................................................................ 9Speciati<strong>on</strong>, Genetic, and Genomic Evoluti<strong>on</strong> in SpartinaM.L. Ainouche, A. Baumel, R. Bayer, K. Fukunaga, T. Cariou and M.T. Misset .................................... 15Evoluti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Hybrids in San Francisco BayD.R. Ayres and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g .................................................................................................................... 23Evolving Invasibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Exotic Spartina Hybrids in Upper Salt Marsh Z<strong>on</strong>es <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco BayM.R. Pakenham-Walsh, D.R. Ayres, and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ............................................................................. 29Varying Success <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spp. Invasi<strong>on</strong>s in China: Genetic Diversity or Differentiati<strong>on</strong>?S. An, Y. Xiao, H. Qing, Z. Wang, C. Zhou, B. Li, S. Shi, D. Yu, Z. Deng, and L. Chen .......................... 33Spartina densiflora x foliosa Hybrids Found in San Francisco BayD.R. Ayres and A.K.F. Lee ...................................................................................................................... 37Fungal Symbiosis: A Potential Mechanism Of Plant <strong>Invasive</strong>nessR.J. Rodriguez, R.S. Redman, M. Hoy, and N. Elder ............................................................................... 39Is Ergot a Natural Comp<strong>on</strong>ent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina Marshes? Distributi<strong>on</strong> and Ecological Host Range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Salt Marsh Claviceps purpureaA.J. Fisher ............................................................................................................................................... 43Mechanisms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sulfide and Anoxia Tolerance in Salt Marsh Grasses in Relati<strong>on</strong> to Elevati<strong>on</strong>alZ<strong>on</strong>ati<strong>on</strong>B.R. Maricle and R.W. Lee ...................................................................................................................... 47Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Salinity <strong>on</strong> Photosyn<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis in C 4 Estuarine GrassesB.R. Maricle, O. Kiirats, R.W. Lee and G.E. Edwards ............................................................................ 55Chapter 2: Spartina Distributi<strong>on</strong> and Spread ................................................................................... 59A Tale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Two Invaded Estuaries: Spartina in San Francisco Bay, California and Willapa Bay,Washingt<strong>on</strong>D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ............................................................................................................................................. 61Spartina In China: Introducti<strong>on</strong>, History, Current Status and Recent ResearchS. An, H. Qing, Y. Xiao, C. Zhou, Z. Wang, Z. Deng, Y. Zhi and L. Chen ............................................... 65Spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco EstuaryK. Zaremba, M. McGowan, and D. R. Ayres ........................................................................................... 73iii

Remote Sensing, LiDAR and GIS Inform Landscape and Populati<strong>on</strong> Ecology, Willapa Bay,Washingt<strong>on</strong>J.C. Civille, S.D. Smith and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ................................................................................................ 83Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Variable Recruitment for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina alterniflora in Willapa Bay,Washingt<strong>on</strong>J.G. Lambrinos, D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g, J.C. Civille and J. Bando ........................................................................ 87Pollen Limitati<strong>on</strong> in a Wind-Pollinated <strong>Invasive</strong> Grass, Spartina alternifloraH.G. Davis, C.M. Taylor, J.G. Lambrinos, J.C. Civille and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ............................................... 91<strong>Invasive</strong> Hybrid Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora x S. foliosa) Recruitment Dynamics in OpenMudflats <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco BayC.M. Sloop, D.R. Ayres and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ................................................................................................ 95The Influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Intertidal Z<strong>on</strong>e and Native Vegetati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Survival and Growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Spartina anglica in Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Puget Sound, WA, USAC.E. Hellquist and R.A. Black ................................................................................................................ 99Will Spartina anglica Invade Northwards with Changing Climate?A.J. Gray and R.J. Mogg ...................................................................................................................... 103Competiti<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g Marsh Macrophytes by Means <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Vertical Geomorphological DisplacementJ.T. Morris ............................................................................................................................................ 109Modeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Hybrids in San Francisco BayR.J. Hall, A.M. Hastings and D.R. Ayres .............................................................................................. 117Modeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spread and C<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina alterniflora in a Pacific EstuaryC.M. Taylor, A. Hastings, H.G. Davis, J.C. Civille and F.S. Grevstad ................................................ 121Hybrid Cordgrass (Spartina) and Tidal Marsh Restorati<strong>on</strong> in San Francisco Bay: If You Build ItThey Will ComeD.R. Ayres and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g .................................................................................................................. 125Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina ..................................................................... 127Assessment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Potential C<strong>on</strong>sequences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Large-scale Eradicati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina anglicafrom <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tamar Estuary, TasmaniaM. Sheehan and J.C. Ellis<strong>on</strong>................................................................................................................. 129Spartina Invasi<strong>on</strong> Changes Intertidal Ecosystem Metabolism in San Francisco BayA.C. Tyler and E.D. Grosholz ............................................................................................................... 135Mechanistic Processes Driving Shifts in Benthic Infaunal Communities Following SpartinaHybrid Tidal Flat Invasi<strong>on</strong>C. Neira, E.D. Grosholz and L.A. Levin ............................................................................................... 141Spartina alterniflora Invasi<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Yangtze River Estuary, China: A SynopsisB. Li, C-Z. Liao, X-D. Zhang, H-L. Chen, Q. Wang, Z-Y. Chen, X-J. Gan, J-H. Wu, B. Zhao,Z-J. Ma, X-L. Cheng, L-F. Jiang, Y-Q. Luo, and J-K. Chen ................................................................. 147The Role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina anglica Producti<strong>on</strong> in Bivalve Diets in Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Puget Sound, WA, USAC.E. Hellquist and R.A. Black .............................................................................................................. 153C<strong>on</strong>trasting Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina foliosa and Hybrid Spartina <strong>on</strong> Benthic InvertebratesE.D. Brusati and E.D. Grosholz ........................................................................................................... 161Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Benthic Invertebrates <strong>on</strong> Sediment Porewater Amm<strong>on</strong>ium and Sulfide: C<strong>on</strong>sequencesfor Spartina Seedling Growth.U.H. Mahl, A.C. Tyler and E.D. Grosholz ............................................................................................ 165Quantifying <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Potential Impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina Invasi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Invertebrate Food Resources foriv

Community Spartina Educati<strong>on</strong> and Stewardship ProjectK. O'C<strong>on</strong>nell ......................................................................................................................................... 265Biological C<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> SpartinaF.S. Grevstad, M.S. Wecker and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g ....................................................................................... 267Ecological Investigati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Enemies for an Interstate Biological C<strong>on</strong>trol Programagainst Spartina GrassesD. Viola, L. Tewksbury and R. Casagrande ......................................................................................... 273Potential for Sediment-Applied Acetic Acid for C<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina alternifloraL.W.J. Anders<strong>on</strong> ................................................................................................................................... 277vi

INTRODUCTION“Maritime Spartina species define and maintain <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shoreline al<strong>on</strong>g broad expanses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperatecoasts where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y are native. The large Spartina species grow lower <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tidal plane than o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rvascular plants; tall, stiff stems reduce waves and currents to precipitate sediments from turbidestuarine waters. With <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> right c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, roots grow upward through harvested sediments toelevate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsh. This engineering can alter <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> physical, hydrological, and ecologicalenvir<strong>on</strong>ments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> salt marshes and estuaries. Where native, Spartinas are uniformly valued, mostlyfor defining and solidifying <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shore. The potential to terrestrialize <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shore was <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rati<strong>on</strong>ale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> scores <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina introducti<strong>on</strong>s. In a time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rising sea levels, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se plants are valued asa barrier to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sea in native areas and in China and Europe where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y have been cultivated. Inc<strong>on</strong>trast, in North America, Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand, and in some parts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> China,n<strong>on</strong>native Spartinas are seen as a bane both to ecology and to human uses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> salt marshes andestuaries” (Str<strong>on</strong>g and Ayres 2009).Three c<strong>on</strong>ferences <strong>on</strong> Spartina were held spread should be developed to understandduring <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last two decades to detail current populati<strong>on</strong> dynamics that could inform c<strong>on</strong>trolunderstanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biological, ecological, and strategies. Attendees recommended <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se basicpolitical repercussi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive Spartina and its steps to address invasive Spartina c<strong>on</strong>trol: identifyc<strong>on</strong>trol. The first internati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>ference <strong>on</strong> a lead agency, appoint a single pers<strong>on</strong> to be ainvasive Spartina was held in Seattle, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, “Spartina Czar,” inventory <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong>,USA in 1990 (Mumford et al. 1991). In additi<strong>on</strong> to identify routes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spread, enlist public support,organizers, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were 31 attendees, 17 evaluate various c<strong>on</strong>trol methods, and c<strong>on</strong>tinuepresentati<strong>on</strong>s, and discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> outcomes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> four workgroup discussi<strong>on</strong>s.regi<strong>on</strong>al strategy workgroups (all <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pacific The sec<strong>on</strong>d c<strong>on</strong>ference was held in Olympia,coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United States). While most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Washingt<strong>on</strong> in 1997 (Patten 1997). There werepresenters were local to Washingt<strong>on</strong> State, 130 attendees from five countries (United States,Spartina researchers also came from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> U.S. East Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and UnitedCoast, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United Kingdom and New Zealand. Kingdom) at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 29 presentati<strong>on</strong>s. Like <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> firstMany questi<strong>on</strong>s were posed at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ference. c<strong>on</strong>ference, it included presentati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> invasiveAttendees deliberated <strong>on</strong> potential changes to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina biology, distributi<strong>on</strong>, impacts, andhabitat (sedimentati<strong>on</strong> rates and detrital c<strong>on</strong>trol. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1997 c<strong>on</strong>ference also hadbreakdown) and fauna (invertebrates, fish, and presentati<strong>on</strong>s addressing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> “political ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>birds) as a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong>, and during and Spartina c<strong>on</strong>trol” (Perkins 1997). Topics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sefollowing c<strong>on</strong>trol. As well, questi<strong>on</strong>s arose <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> papers included public activities, and riskefficacies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biological, chemical and mechanical assessment associated with c<strong>on</strong>trol measures; “<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>c<strong>on</strong>trol methods, and potential c<strong>on</strong>straints <strong>on</strong> hysteria over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cordgrass” (Cohen 1997) andmethod — envir<strong>on</strong>mental, political and/or “<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> crisis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> civil dialogue” (Markham 1997)ec<strong>on</strong>omic. It was agreed that models <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina were noted. New topics at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1997 c<strong>on</strong>ferencevii

included <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> documentati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hybrids betweenS. alterniflora and S. foliosa in San Francisco Bay(Daehler and Str<strong>on</strong>g 1997), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> GISmapping and associated databases to inventoryand model future spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina (Harringt<strong>on</strong>et al. 1997), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first empirical data <strong>on</strong> drift <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Spartina seed (Sayce et al. 1997), increases inshorebird populati<strong>on</strong>s after Spartina die-back in<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United Kingdom (Gray et al. 1997), andcomparis<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> benthic invertebrates betweenSpartina stands and mudflat (Luiting et al. 1997).Attendees suggested that additi<strong>on</strong>al research bec<strong>on</strong>ducted to develop models <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>dynamics and genetic shifts, to m<strong>on</strong>itor spread andenvir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive Spartina, toimprove mapping and modeling in order to helpprioritize c<strong>on</strong>trol and evaluate costs. They alsoproposed carrying out research to quantifysediment accreti<strong>on</strong> rates in invaded areascompared with n<strong>on</strong>-invaded habitats, to evaluatephysiological tolerance and vulnerabilities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Spartina, assess envir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts associatedwith Spartina removal and specific c<strong>on</strong>troltechniques.The third internati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>ference <strong>on</strong> invasiveSpartina was held in San Francisco, California in2004. Hosted by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California State CoastalC<strong>on</strong>servancy and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> U.S. Envir<strong>on</strong>mentalProtecti<strong>on</strong> Agency, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> meeting drew 147presenters and attendees from seven countries,including China, France, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United States,Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> UnitedKingdom. Fifty-seven oral and posterpresentati<strong>on</strong>s were shared; 40 <strong>on</strong> science and 17<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol or management. Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 11 papers <strong>on</strong>Spartina biology in this volume, half were focused<strong>on</strong> genetics, with Spartina hybridizati<strong>on</strong>s being<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary c<strong>on</strong>text for genetics studies. Thirteenpapers <strong>on</strong> distributi<strong>on</strong> and spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartinaincluded spatio-temporal analysis using GIStechniques, predicti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spread due tocompetiti<strong>on</strong>, climate change, evoluti<strong>on</strong>, andrestorati<strong>on</strong>; dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed set and seedlingrecruitment; and two simulati<strong>on</strong> models describingspread. Studies <strong>on</strong> impacts to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecosystemranged from increased sedimentati<strong>on</strong> underSpartina canopies, to changes in invertebrateviiicommunities and food webs, to shifts in birdcommunities, populati<strong>on</strong>s, and behaviors due to<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina invasi<strong>on</strong>.Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 17 papers <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol and management,seven papers were focused <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol per se,while five detailed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tentimes complex andbureaucracy-laden routes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina c<strong>on</strong>trol inSan Francisco Bay, Washingt<strong>on</strong> State, Tasmaniaand New Zealand — mostly benefiting from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>perspective <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hindsight. Two papers c<strong>on</strong>sidered<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>on</strong>g and hard task that lies ahead to restoreestuaries that have underg<strong>on</strong>e major increases inmarsh elevati<strong>on</strong> due to Spartina invasi<strong>on</strong> — whatHacker and Dethier (this volume) called <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>“legacy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong>.”A primary reas<strong>on</strong> for hosting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2004Spartina c<strong>on</strong>ference in San Francisco was to giveparticipants a first-hand look at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong>,through helicopter and “mud-level” field trips —with an eye toward assessing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>invasi<strong>on</strong>, and determining whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r c<strong>on</strong>trol was, infact, feasible or even necessary. These questi<strong>on</strong>swere discussed by an expert panel at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>c<strong>on</strong>ference. Overwhelmingly, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> panel agreedthat c<strong>on</strong>trol was both possible and urgentlyneeded. With this unequivocal recommendati<strong>on</strong>,<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California State Coastal C<strong>on</strong>servancyproceeded to fund and coordinate an aggressiveregi<strong>on</strong>al program to eradicate introduced Spartina(including hybrids) from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San FranciscoEstuary. By fall 2010, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> program hadsuccessfully reduced <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive Spartinafrom more than 800 net acres in 2005, to less than100 net acres, a reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 90 percent. Theprogram is <strong>on</strong>going, with full effective eradicati<strong>on</strong>expected before 2020.The papers that follow in this c<strong>on</strong>ferenceproceedings volume detail <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> advances that havebeen made in our understanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartinabiology and demography, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>oundenvir<strong>on</strong>mental effects that result from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>seinvasi<strong>on</strong>s worldwide, and suggest <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> scope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>unresolved issues.Debra AyresUniversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Davis

REFERENCESCohen E.S. 1997. Local Spartina management planning forcommunity oriented research and development. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K.,ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>.Washingt<strong>on</strong> State University Cooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>gBeach, WA. pp. 58-59.Daehler C.C. and D.R. Str<strong>on</strong>g. 1997. Invasi<strong>on</strong>s and hybridizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>cordgrasses, Spartina spp. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d<str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong>State University Cooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. p. 17.Gray A.J., A.F. Raybould and S.L. Brown. 1997. Theenvir<strong>on</strong>mental impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina anglica: past, present andpredicted. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina<str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong> State UniversityCooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. pp. 39-45.Hacker S.D. and M.N. Dethier. Where do we go from here?Alternative c<strong>on</strong>trol and restorati<strong>on</strong> trajectories for a marine grass(Spartina anglica) invader in different habitat types. In: Ayres,D.R., D.W. Kerr, S.D. Erics<strong>on</strong> and P.R. Ol<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<strong>on</strong>, eds.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong>Spartina, 2004 Nov 8-10, San Francisco, CA, USA. SanFrancisco Estuary <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Project <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> CaliforniaState Coastal C<strong>on</strong>servancy: Oakland, CA. (this volume).Harringt<strong>on</strong> J.A., M.B. Harringt<strong>on</strong> and C.J. Berlin. 1997. ModelingSpartina in Willapa Bay. . In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d<str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong>State University Cooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. pp.23-26.Luiting V.T., J.R. Cordell, A.M. Olso and C.A. Simenstad. 1997.Does exotic Spartina alterniflora change benthic invertebrateassemblage? In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina<str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong> State UniversityCooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. pp. 48-50.Markham D.C. 1997. Sustainable development and Spartinac<strong>on</strong>trol – a case study <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> crisis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> civil dialog. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K.,ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>.Washingt<strong>on</strong> State University Cooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>gBeach, WA. pp. 64-67.Mumford T.F, P. Peyt<strong>on</strong>., J.R. Sayce. and S. Harbell, eds. 1991.Spartina Workshop Record. Washingt<strong>on</strong> Sea Grant Program,University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Washingt<strong>on</strong>, Seattle.Perkins J.H. 1997. The political ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina andglyphosate. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina<str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong> State UniversityCooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. p. 82.Patten, K., ed. 1997. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong> State University CooperativeExtensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA.Sayce K., B. Dumbauld and J. Hidy. 1997. Seed dispersal in drift <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Spartina alterniflora. In: Patt<strong>on</strong>, K., ed. Sec<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g>Spartina <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Washingt<strong>on</strong> State UniversityCooperative Extensi<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>g Beach, WA. pp. 27-31.Str<strong>on</strong>g, D.R. and D.R. Ayres. 2009. Spartina Introducti<strong>on</strong>s andC<strong>on</strong>sequences in Salt Marshes: Arrive, Survive, Thrive, andsometimes Hybridize. In: Silliman B.R., E. Grosholz and M.Bertness, eds. Human Impacts <strong>on</strong> Salt Marshes: A GlobalPerspective. University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Press, Berkeley, CAix

CHAPTER ONESpartina Biology

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaChapter 1: Spartina BiologyCALIFORNIA CORDGRASS (SPARTINA FOLIOSA), AN ENDEMIC OF SALT MARSH HABITATSALONG THE PACIFIC COAST OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICAM.C. VASEYDepartment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA 94132; andDepartment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Studies, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064; mvasey@sfsu.eduCalifornia cordgrass (Spartina foliosa) is an endemic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Floristic Province in westernNorth America. This paper reviews its historic and c<strong>on</strong>temporary distributi<strong>on</strong>, pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>iles its habitatcharacteristics including key adaptive traits, and makes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> case that S. foliosa should be recognizedas a foundati<strong>on</strong> species within salt marshes characteristic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Floristic Province. Thisinformati<strong>on</strong> is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n c<strong>on</strong>sidered in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> introgressive hybridizati<strong>on</strong> between S. foliosa and<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> closely related Spartina alterniflora. Clearly, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hybrid between S. foliosa and S. alterniflora isprogressively spreading genes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. alterniflora into pure stands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa throughout <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> SanFrancisco Bay estuary. While this raises a c<strong>on</strong>cern about <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential “extincti<strong>on</strong>” <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa as adistinct genotype, it is suggested that a greater problem may be <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecological implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thisintrogressi<strong>on</strong> for salt marshes in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Bay estuary. Ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than eradicati<strong>on</strong> per se, it issuggested that focused c<strong>on</strong>tainment may be <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> best strategy for minimizing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thishybrid <strong>on</strong> salt marshes in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Floristic Province <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this regi<strong>on</strong>. Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, c<strong>on</strong>tinued adaptivemanagement studies that evaluate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this species <strong>on</strong> salt marsh restorati<strong>on</strong> arerecommended.INTRODUCTIONIn this review, I will examine what we know aboutCalifornia cordgrass and attempt to frame this discussi<strong>on</strong> in<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> management challenges thatinvasive Spartina alterniflora pose to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Bayestuary. The approach will be to discuss what is known <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> historic and c<strong>on</strong>temporary distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartinafoliosa, to focus <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> suite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adaptive traits that makes S.foliosa such an important comp<strong>on</strong>ent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> low marsh habitatsin west coast estuaries, and to pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ile S. foliosa as a“foundati<strong>on</strong> species” in this envir<strong>on</strong>ment. I will <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>nsummarize this informati<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> threats posedby hybridizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foloiosa with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive Spartinaalterniflora.HISTORIC AND CONTEMPORARY DISTRIBUTION OFSPARTINA FOLIOSAMacD<strong>on</strong>ald and Barbour (1974) c<strong>on</strong>ducted a survey <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>salt marsh vegetati<strong>on</strong> al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> North American Pacificcoast ranging from Point Barrow, Alaska to Cabo San Lucas,Baja California. In general, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y found three dominant saltmarsh vegetati<strong>on</strong> communities over this extensive range: anarctic, boreal, and north temperate assemblage is dominatedby nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn grasses such as Deschampsia caespitosa andsedge species such as Carex lygnbyei, which ranges from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>Seward Peninsula down to Drake’s Estero in Marin County;a south temperate and subtropical assemblage ranges fromSan Francisco Bay to Laguna San Ignacio in Baja California,which is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> assemblage occupied by S. foliosa; and south <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>this regi<strong>on</strong>, tropical mangrove forests and scrub assemblagesdominate estuarine tidal wetlands.The historic distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa occurs in thisintermediate z<strong>on</strong>e, also known as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California FloristicProvince (Raven and Axelrod 1978). The California FloristicProvince occurs al<strong>on</strong>g a cism<strong>on</strong>tane regi<strong>on</strong> from sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rnOreg<strong>on</strong> down through nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Baja California. It ischaracterized by a Mediterranean-type climate c<strong>on</strong>sisting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>l<strong>on</strong>g, hot and dry summers punctuated by short, wet and coldwinters. The California Floristic Province has recently beenrecognized as <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> twenty-five global “biodiversity hotspots,” with over 48% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species being endemics(Myers et al. 2000; Calsbeek et al. 2003). Spartina foliosa isam<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se endemic species.The particular distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa occurs in twomajor disjunct regi<strong>on</strong>s: (1) nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn California (SanFrancisco Bay regi<strong>on</strong>) and, approximately 565 kilometersaway, (2) a series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> geographically proximal populati<strong>on</strong>sfrom Orange County in sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn California through southcentralBaja California. The historic nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Californiadistributi<strong>on</strong> has been c<strong>on</strong>fused by <strong>on</strong>e case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>misidentificati<strong>on</strong> and two o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r cases <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> relatively recentnor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn range extensi<strong>on</strong>s. The case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> misidentificati<strong>on</strong> wasfirst recognized by P. Faber (pers<strong>on</strong>al communicati<strong>on</strong>) whoperceived that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extensive stands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina l<strong>on</strong>grecognized in Humboldt Bay wetlands were actuallySpartina densiflora (a caespitose species from SouthAmerica) ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than S. foliosa. Later, Spicher and Josselyn(1985) published a c<strong>on</strong>firmati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this observati<strong>on</strong>.Barnhart et al. (1992) speculate that S. densiflora may havebeen introduced to Humboldt Bay as l<strong>on</strong>g ago as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1860sas part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shingle or dry ballast deposited during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> height<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shipping activities in this formerly bustling port. Spicher-3-

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartinaand Josselyn (1985) also reported a local populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S.foliosa at Bodega Bay; however, this populati<strong>on</strong> was almostcertainly not present when Barbour (1970) and MacD<strong>on</strong>aldand Barbour (1974) reported <strong>on</strong> salt marsh vegetati<strong>on</strong> inBodega Bay wetlands. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1990s, a large populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S.foliosa was observed col<strong>on</strong>izing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> accreting delta <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Lagunitas Creek in sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Tomales Bay (Baye 2004,pers<strong>on</strong>al communicati<strong>on</strong>). Howell (1949, 1970) in his flora<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Marin, however, does not menti<strong>on</strong> this locality for S.foliosa nor do any historic herbarium collecti<strong>on</strong>s suggest thatei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Bodega Bay or Tomales Bay populati<strong>on</strong>s occurredprior to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> latter part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> twentieth century. MacD<strong>on</strong>aldand Barbour (1974) specifically remark up<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> absence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>S. foliosa in Tomales Bay.On <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r hand, Howell (1949, 1970) and historicherbarium collecti<strong>on</strong>s do c<strong>on</strong>firm that S. foliosa hashistorically been found in Drake’s Estero in sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn PointReyes as well as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> relatively nearby Bolinas Lago<strong>on</strong> inMarin County. O<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se two outer coastal estuaries,all o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r historic nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn California populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosaare found within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Bayestuary, ranging from tidal wetlands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> South San FranciscoBay up through San Pablo Bay and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower tidal wetlands<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Petaluma River, S<strong>on</strong>oma Creek, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Napa River.Spartina foliosa c<strong>on</strong>tinues up into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Carquinez Straightsbut is largely unknown from Suisun Bay. In this easternregi<strong>on</strong>, it is apparently c<strong>on</strong>strained by low brackish marshvegetati<strong>on</strong> dominated by Schoenoplectus acutus andSchoenoplectus californicus and its distributi<strong>on</strong> is dynamicdepending <strong>on</strong> decadal shifts in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> salinity gradient in thisporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary. It is somewhat remarkable that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>reare no historic or current occurrences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>Golden Gate south al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> central California coast to PointC<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>, including likely tidal wetlands such as ElkhornSlough and Morro Bay. Peter Baye (pers<strong>on</strong>alcommunicati<strong>on</strong> 2004) suggests that before <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> jetties, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se central Californian lago<strong>on</strong>s were not tidalduring summers (due to low flows) so it is possible that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ydid not provide suitable habitat.In summary, S. foliosa in nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn California washistorically c<strong>on</strong>centrated within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower, saline reaches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Bay estuary where it was an importantc<strong>on</strong>stituent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extensive salt marshes that historicallydominated tidal wetlands in this regi<strong>on</strong>. It appears to beslowly moving north al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> coast and is now present inBodega Bay. Its eastern distributi<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San FranciscoBay estuary is dynamic and dependant <strong>on</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g-term shifts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> salinity gradient in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Carquinez Straight and lowerSuisun Bay subregi<strong>on</strong>.The sec<strong>on</strong>d historic center <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> for S. foliosais relatively well documented by MacD<strong>on</strong>ald and Barbour(1974), Trnka and Zedler (2000), and Wiggins (1980). Thenor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rnmost historic locality is Mugu Lago<strong>on</strong> (OrangeCounty), c<strong>on</strong>siderably south <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Point C<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>. There is<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n a fairly c<strong>on</strong>tinuous occurrence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. foliosa whereverc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s are suitable down to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tijuana Estuary in SanDiego County (e.g. Anaheim Bay, Bolsa Chica Bay,Newport Bay, Santa Margarita River, Los PeñasquitosLago<strong>on</strong>, San Elijo Lago<strong>on</strong>, San Diegito Lago<strong>on</strong>, Missi<strong>on</strong>Bay, and San Diego Bay). This distributi<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tinues in arelatively c<strong>on</strong>sistent fashi<strong>on</strong> al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> BajaCalifornia in Estero de Punta Banda, Bahia de San Quintin,Laguna Guerrero Negro, Ojo de Liebre, Laguna San Ignacio,and Bahia de la Magdalena. It is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interest that Bahia de laMagdalena is at a boundary between tropical and subtropicalmarine ecosystems. It may be that S. foliosa is able to extendfur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r south than most California Floristic Province plantendemics because it is resp<strong>on</strong>ding as much to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se marineinfluences as to Mediterranean climate influences. South <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Laguna Guerrero Negro, S. foliosa begins to co-occur withmangroves and mangrove-like shrubs such as Rhizophoramangle, Laguncularia racemosa, C<strong>on</strong>ocarpus erecta, andAvicennia germinans. MacD<strong>on</strong>ald and Barbour (1974) pointout that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se same mangrove associates co-occur withsmooth cordgrass (S. alterniflora) in marshes near Tabasco<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gulf <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mexico. Thus, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> closest geographic distancebetween California cordgrass and smooth cordgrass is at S.foliosa’s sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn distributi<strong>on</strong>al limit. There are <strong>on</strong>ly about1,200 kilometers separating <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gulf coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mexico from<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pacific coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Baja California.HABITAT CHARACTERISTICS AND ADAPTIVE TRAITSThroughout its entire range, S. foliosa occupies adistinctive z<strong>on</strong>e associated with coastal salt marshes. In mostcases, it is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>ly vascular plant species present in thisz<strong>on</strong>e, which roughly corresp<strong>on</strong>ds to bay or channel marginsat or near <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean high tide line (Schoenherr 1995). Everyday, S. foliosa habitat is inundated by salt water for <strong>on</strong>e toseveral hours. Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, it is exposed to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> forces <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> waveacti<strong>on</strong> and high velocity channel flows. This combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>high salinity, prol<strong>on</strong>ged inundati<strong>on</strong>, and daily hydrologicaldisturbance is obviously bey<strong>on</strong>d <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tolerance limits foro<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r salt marsh vascular plant species. Spartina foliosa isable to tolerate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se extreme c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a uniquesuite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adaptive traits that include: (1) C4 photosyn<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis, aphysiological drought-adaptive mechanism which meansthat about half as much water is needed for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same amount<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carbohydrate produced; (2) epidermal salt glands whichalso help to c<strong>on</strong>serve water by reducing salt c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>sin cell sap; (3) possessi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> deep rhizomes (about 15 cm)which regenerate new segments each seas<strong>on</strong> and createextensive, branching mats that penetrate anaerobic sedimentsand anchor shoreline habitat; (4) stems and leaves that arecomposed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> aerenchymous tissue that allows oxygen totravel from aerial porti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant down to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rhizomesthat are embedded in anaerobic sediments; and (5) stems andleaves that are about <strong>on</strong>e meter tall, enabling vegetativestructures to remain above extreme high tide levels so thatoxygen can reliably be transported to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> roots.-4-