English 2.28MB - Center for International Forestry Research

English 2.28MB - Center for International Forestry Research

English 2.28MB - Center for International Forestry Research

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions<br />

on the Edge of a Conservation Area,<br />

Khe Tran Village, Vietnam<br />

Manuel Boissière • Imam Basuki • Piia Koponen<br />

Meilinda Wan • Douglas Sheil

National Library of Indonesia Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Boissière, Manuel<br />

Biodiversity and local perceptions on the edge of a conservation area, Khe<br />

Tran village, Vietnam/ by Manuel Boissière, Imam Basuki, Piia Koponen,<br />

Meilinda Wan, Douglas Sheil. Bogor, Indonesia: <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Forestry</strong> <strong>Research</strong> (CIFOR), 2006.<br />

ISBN 979-24-4642-7<br />

106p.<br />

CABI thesaurus: 1. nature reserve 2. nature conservation<br />

3. landscape 4. biodiversity 5. assessment 6. community involvement<br />

7. Vietnam I. Title<br />

© 2006 by CIFOR<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Printed by Inti Prima Karya, Jakarta<br />

Revised edition, June 2006<br />

Design and layout by Catur Wahyu and Gideon Suharyanto<br />

Photos by Manuel Boissière and Imam Basuki<br />

Maps by Mohammad Agus Salim<br />

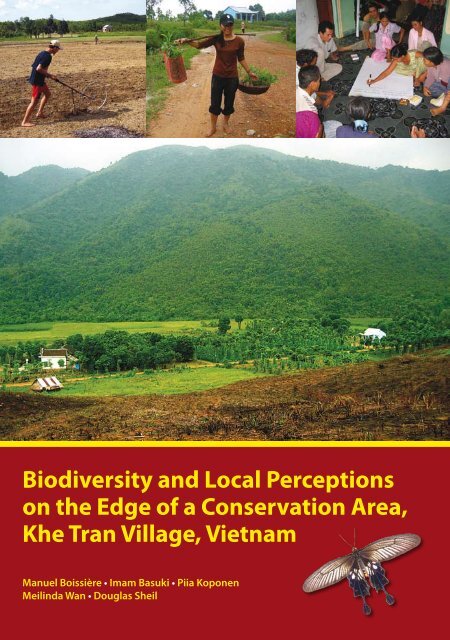

Cover photos, from left to right:<br />

- A villager prepares the soil <strong>for</strong> peanut plantation in a <strong>for</strong>mer rice field, Khe Tran<br />

- A young woman carries Acacia seedling ready to be planted<br />

- Villagers discuss the future of Phong Dien Nature Reserve<br />

- The different land types in Khe Tran: bare land, village with home gardens, rice fields, and<br />

protected mountain areas<br />

Published by<br />

<strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Forestry</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang<br />

Bogor Barat 16680, Indonesia<br />

Tel.: +62 (251) 622622; Fax: +62 (251) 622100<br />

E-mail: ci<strong>for</strong>@cgiar.org<br />

Web site: http://www.ci<strong>for</strong>.cgiar.org

Contents<br />

Acronyms and terms vii<br />

Acknowledgements ix<br />

1. <strong>Research</strong> context and objectives 1<br />

2. Methods 3<br />

Village activities 3<br />

Field activities 4<br />

3. Achievements 8<br />

4. Conservation context in Khe Tran 10<br />

4.1. Previous conservation activities 10<br />

4.2. Government programs that affected Khe Tran village 12<br />

Summary 14<br />

5. Site description 15<br />

5.1. <strong>Research</strong> site 15<br />

5.2. People from Khe Tran 17<br />

5.3. Land use and natural resources 23<br />

Summary 28<br />

6. Local perceptions of the different land types and resources 29<br />

6.1. Local land uses 29<br />

6.2. Land type importance 31<br />

6.3. Forest importance 32<br />

6.4. Forest importance in the past, present and future 34<br />

6.5. Importance according to source of products 36<br />

6.6. Most important products from the <strong>for</strong>est 37<br />

6.7. Threats to local <strong>for</strong>ests and biodiversity 41<br />

6.8. People’s hopes <strong>for</strong> the future of their <strong>for</strong>est and life 42<br />

Summary 45<br />

iii

iv | Contents<br />

7. Characterization of land types 46<br />

7.1. Sampling of land types 46<br />

7.2. Specimen collection and identification 48<br />

7.3. Plant biodiversity 51<br />

7.4. Forest structure 53<br />

7.5. Species vulnerability 55<br />

Summary 58<br />

8. Ethno-botanical knowledge 59<br />

8.1. Plant uses 59<br />

8.2. Species with multiple uses 61<br />

8.3. Uses of trees 62<br />

8.4. Uses of non-trees 62<br />

8.5. Forest as resource of useful plants 64<br />

8.6. Nonsubstitutable species 65<br />

8.7. Remarks on potential uses of species 66<br />

Summary 66<br />

9. Local perspectives on conservation 67<br />

Summary 70<br />

10. Conclusion and recommendations 71<br />

10.1. Conclusion 71<br />

10.2. Recommendations 75<br />

Bibliography 77<br />

Annexes 79<br />

1. LUVI (mean value) of important plant species by different use<br />

categories (result based on scoring exercise of four groups of in<strong>for</strong>mant) 79<br />

2. LUVI (mean value) of important animal species by different use<br />

categories based on scoring exercise of four groups of in<strong>for</strong>mant 83<br />

3. The botanical names, families and local name of specimens collected<br />

within and outside the plots by their use categories 84

Tables and figures<br />

Tables<br />

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions | v<br />

1. Composition of MLA research team in Khe Tran village 3<br />

2. Important events affecting the local livelihoods 21<br />

3. Income range by source of products and settlement area 22<br />

4. Identified land types in Khe Tran 24<br />

5. Regrouped land types in Khe Tran 25<br />

6. Important <strong>for</strong>est plants and their local uses 30<br />

7. Main categories of use of plant and animal resources 30<br />

8. Local importance of land types by use category (all groups) 33<br />

9. Forest importance by use categories (all groups) 33<br />

10. Forest importance over time according to different use categories<br />

(all groups) 35<br />

11. Importance (%) of source of product by gender 37<br />

12. Most important <strong>for</strong>est plants and animals in Khe Tran (all groups) 39<br />

13. Most important <strong>for</strong>est plants by categories of use (all groups) 40<br />

14. Most important <strong>for</strong>est animals by categories of use (all groups) 40<br />

15. Locally important plant species by use category and IUCN list<br />

of threatened trees 41<br />

16. Villagers’ perception on threats to <strong>for</strong>est and biodiversity (19 respondents) 42<br />

17. Villagers’ perception about <strong>for</strong>est loss (19 respondents) 43<br />

18. Villagers’ ideas on threats to human life (19 respondents) 43<br />

19. Summary of specimen collection and identification of plant species<br />

from 11 sample sites 50<br />

20. Plant richness in Khe Tran 53<br />

21. Main tree species based on basal area and density listed with their<br />

uses in Khe Tran 54<br />

22. Richness (total number of species recorded per plot) of life <strong>for</strong>ms<br />

of non-tree species in all land types in Khe Tran 55<br />

23. Threatened species in Khe Tran based on vegetation inventories<br />

and PDM exercises 57<br />

24. Summary of specimen collection and identification of plant species<br />

from 11 sample sites 59<br />

25. Mean number of species and number of useful species recorded<br />

in each land type 60<br />

26. Distribution of all useful plant species per plot and by use category 61<br />

27. Plant species with at least four uses 62<br />

28. Distribution of tree species considered useful per plot and per use category 63<br />

29. Distribution of non-tree species considered useful per plot and per use<br />

category 64<br />

30. Villager’s perceptions on conservation and Phong Dien Nature Reserve 69

vi | Contents<br />

Figures<br />

1. Scoring exercise (PDM) with Khe Tran men group 5<br />

2. Working on sample plot 6<br />

3. Location of Khe Tran village in the buffer zone of Phong Dien<br />

Nature Reserve 16<br />

4. Situation of Khe Tran village 18<br />

5. Livestock and Acacia plantations are important in Khe Tran 20<br />

6. A woman from the lower part of the village harvests rubber<br />

from her plantation 22<br />

7. Considerable areas of bare land are used in Khe Tran <strong>for</strong> new<br />

Acacia plantation 25<br />

8. Biodiversity and resource distribution map of Khe Tran 27<br />

9. Land type by importance (all groups) 31<br />

10. Importance of <strong>for</strong>est types (all groups) 32<br />

11. Forest importance over time (all groups) 35<br />

12. Source of product importance (all groups) 37<br />

13. Importance of <strong>for</strong>est resources by use categories (all groups) 38<br />

14. Recent flood on a bridge between Phong My and Khe Tran 44<br />

15. Field sampling of land types in Khe Tran (total sample size 11 plots) 47<br />

16. Distribution of sample plots in the research area 49<br />

17. Accumulation of non-tree species with the increasing random<br />

order of subplots (each 20 m 2 ) <strong>for</strong> various land types in Khe Tran 50<br />

18. Relative dominance in primary and secondary <strong>for</strong>est plots in Khe Tran<br />

based on basal area 52<br />

19. Forest structural characteristics in Khe Tran. Left panel: basal area and<br />

density; right panel: tree height, stem diameter and furcation index 56<br />

20. All plant species considered useful by the Khe Tran villagers shown<br />

in use categories 63<br />

21. Total number of all useful plant species per category in primary,<br />

secondary and plantation <strong>for</strong>ests 65

Acronyms and terms<br />

asl above sea level<br />

CBEE Community-Based Environmental Education<br />

CIFOR <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Forestry</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

CIRAD Centre de coopération <strong>International</strong>e en Recherche Agronomique<br />

pour le Développement<br />

dbh diameter at breast height<br />

DPC District Peoples Committee<br />

ETHZ Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (Federal Institute of<br />

Technology in Zürich)<br />

ETSP Extension and Training Support Project<br />

FIPI <strong>Forestry</strong> Inventory and Planning Institute<br />

FPD Forest Protection Department<br />

GoV Government of Vietnam<br />

HUAF Hue University of Agriculture and <strong>Forestry</strong><br />

IUCN <strong>International</strong> Union <strong>for</strong> Conservation of Nature and Natural<br />

Resources<br />

Land type component of landscape that is covered by natural coverage or used<br />

<strong>for</strong> human activities<br />

Land use component of landscape that is used <strong>for</strong> human activities<br />

Landscape holistic and spatially explicit concept that is much more than the<br />

sum of its components e.g. terrain, soil, land type and use<br />

Lowlands village area on the lower reaches of O Lau river<br />

vii

viii | Acronyms and terms<br />

LUVI Local User Value Index<br />

MLA Multidisciplinary Landscape Assessment<br />

NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product<br />

PDM Pebble Distribution Method<br />

PDNR Phong Dien Nature Reserve<br />

PPC Province Peoples Committee<br />

SDC Swiss Development Cooperation<br />

SFE State Forest Enterprises<br />

TBI-V Tropenbos <strong>International</strong>-Vietnam<br />

Uplands village area on the upper reaches of O Lau river<br />

USD US Dollar<br />

Village group of households included in a commune (subdistrict level) but<br />

not recognised as a legal entity in Vietnam<br />

VND Vietnamese Dong (USD 1 approximately equals to VND 15,700)<br />

WWF World Wildlife Fund

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to express our profound gratitude to individuals and institutions <strong>for</strong><br />

their assistance in the course of undertaking this research. We wish to thank the<br />

representatives of the Government of Vietnam, the Provincial Peoples Committee<br />

(PPC) of Thua Thien Hue province, Peoples Committee of Phong Dien district<br />

and Phong My commune <strong>for</strong> their interest in our work.<br />

Our appreciations are addressed to Tran Huu Nghi, Jinke van Dam, Tu<br />

Anh, Nguyen Thi Quynh Thu, from Tropenbos <strong>International</strong> Vietnam, <strong>for</strong> their<br />

cooperation and <strong>for</strong> their assistance in organising our surveys.<br />

We were lucky to collaborate with all the MLA participants: Le Hien (Hue<br />

University of Agriculture and <strong>Forestry</strong>), Ha Thi Mung (Tay Nguyen University),<br />

Vu Van Can, Nguyen Van Luc (FIPI), Nguyen Quy Hanh and Tran Thi Anh<br />

Anh (Department of Foreign Affairs of Thua Thien Hue province), and Ho Thi<br />

Bich Hanh (Hue College of Economics) <strong>for</strong> their hard work and interest <strong>for</strong> the<br />

project.<br />

We would like to thank Patrick Rossier (ETSP-Helvetas), Eero Helenius<br />

(Thua Thien Hue Rural Development Programme), and Chris Dickinson (Green<br />

Corridor Project-WWF), <strong>for</strong> their useful suggestions.<br />

We wish to thank Ueli Mauderli (SDC), Jean Pierre Sorg (ETHZ), <strong>for</strong> their<br />

useful comments and suggestions during their survey in Khe Tran, Jean-Laurent<br />

Pfund and Allison Ford (CIFOR) <strong>for</strong> their valuable comments during the redaction<br />

of the report, Michel Arbonnier (CIRAD) <strong>for</strong> the revision of the plant list, Henning<br />

Pape-Santos, our copy-editor, and Wil de Jong, the coordinator of the project <strong>for</strong><br />

his support.<br />

Last but not the least, we would like to thank the villagers from Khe Tran, Son<br />

Qua and Thanh Tan <strong>for</strong> their cooperation during our different surveys, <strong>for</strong> their<br />

patience and <strong>for</strong> all the in<strong>for</strong>mation they provided to us.<br />

ix

. <strong>Research</strong> context and objectives<br />

Vietnam has been re<strong>for</strong>ming its <strong>for</strong>est management in favour of household and<br />

local organization (Barney 2005). The government increasingly gives local people<br />

the right to manage the <strong>for</strong>ests. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, in this changing environment,<br />

recognition of local people’s rights is still limited and local knowledge and<br />

perspectives are rarely taken into account by the state institutions implementing<br />

land titling and decentralization. The challenge is to better in<strong>for</strong>m each stakeholder<br />

on the perspectives of people living in and near the <strong>for</strong>est on the natural resources<br />

and landscapes. Furthermore, clarification of the local capacity to manage <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

is necessary <strong>for</strong> better in<strong>for</strong>med decision making.<br />

Stakeholder and biodiversity at the local level is a three-year collaboration<br />

between the <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Forestry</strong> <strong>Research</strong> (CIFOR) and the Swiss<br />

Development Cooperation (SDC). Tropenbos <strong>International</strong>-Vietnam (TBI-V)<br />

has been a very helpful collaborator <strong>for</strong> coordinating the project activities. The<br />

project goal is to contribute to the enhancement of the livelihoods of local <strong>for</strong>est<br />

dependent communities and sustainable <strong>for</strong>est management. The project aims to<br />

strengthen local capacity to plan and implement locally relevant <strong>for</strong>est landscape<br />

management as a mechanism to achieve those goals. It focuses on situations where<br />

decentralization has given local government more authority and responsibility <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong>ests. The project fosters better engagement by local decision-makers that takes<br />

into consideration the needs and preferences of local people, especially the poor<br />

communities.<br />

Multidisciplinary landscape assessment, or MLA, is a set of methods developed<br />

by CIFOR scientists to determine ‘what is important to local communities, in<br />

terms of landscape, environmental services, and resources’. The approach is<br />

rooted in social (anthropology, ethnobotany and socio-economics) as well as<br />

natural sciences (botany, ecology, geography and pedology); was tested and used<br />

in different countries (Bolivia, Cameroon, Gabon, Indonesia, Mozambique and<br />

Philippines). The methods are fully detailed in four languages: <strong>English</strong>, French,<br />

Indonesia and Spanish (Sheil et al. 2003; http://www.ci<strong>for</strong>.cgiar.org/mla/).

| <strong>Research</strong> context and objectives<br />

MLA helps the project by providing in<strong>for</strong>mation on the way local people<br />

articulate and document their knowledge of land and natural resources uses. Local<br />

knowledge is considered crucial in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong> the management of <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Finally, in this report we aim to provide in<strong>for</strong>mation on the way the local<br />

community in Khe Tran (Phong My commune, Phong Dien district, Thua Thien<br />

Hue province) perceives and manages its environment, and we discuss the options<br />

it has to participate in future nature reserve management.

. Methods<br />

The multidisciplinary approach of MLA gathers in<strong>for</strong>mation on land use in village<br />

and field, and studies local perceptions on <strong>for</strong>est landscapes and resources as well<br />

as local priorities in terms of land management and which land types, resources<br />

and activities are important to local people. The MLA team, working in both<br />

village and field, was composed by scientists from different disciplines (Table 1).<br />

Table 1. Composition of MLA research team in Khe Tran village<br />

Team member Responsibility/research aspect Contact<br />

Manuel Boissière Team coordinator/ethnobotany m.boissiere@cgiar.org<br />

Ha Thi Mung Socio-economy mungbmt@yahoo.com<br />

Imam Basuki Socio-economy i.basuki@cgiar.org<br />

Le Hien Socio-economy Hienle2001@yahoo.com<br />

Meilinda Wan Socio-economy m.wan@cgiar.org<br />

Douglas Sheil Ecology d.sheil@cgiar.org<br />

Piia Koponen Ecology p.koponen@cgiar.org<br />

Nguyen Van Luc Botany vanluc_qh@yahoo.com.vn<br />

Vu Van Can Botany Tel. 04-861-6946<br />

Ho Thi Bich Hanh Translator hanhdhkt@gmail.com<br />

Nguyen Quy Hanh Translator Quyhanh2000@yahoo.com<br />

Tran Thu Anh Anh Translator hianhanh@yahoo.com<br />

Village activities<br />

Consisting of one or two researchers assisted by a translator, the village team was<br />

responsible <strong>for</strong> all socio-economic data collection. The team used questionnaire<br />

and data sheets to interview most households and key in<strong>for</strong>mants and to record

| Methods<br />

the results of community meetings and focus group discussions. In<strong>for</strong>mation was<br />

gathered from each household head on socio-economic aspects (demography,<br />

sources of income and livelihoods) and some other cultural aspects (history of<br />

the village, social organization, stories and myths, religion). The questionnaire<br />

and data sheets also provided basic in<strong>for</strong>mation on local views by gender, threats<br />

against biodiversity and <strong>for</strong>ests, perspectives on natural resource management and<br />

conservation, and land tenure.<br />

Participatory mapping exercises began during the very first days of the survey<br />

with two women and men groups of villagers using two basic maps, assisted by<br />

two research members to explain the objectives of the exercise. They facilitated<br />

the process through discussion with villagers about which resources and land<br />

types to add to the basic maps. These maps were then put together to build a single<br />

map representing the perception of the overall community. During all our onsite<br />

activities, the map was available to any villager <strong>for</strong> adding features and making<br />

corrections. In the case of Khe Tran, we worked a second time with a group of key<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mants to increase the precision of the map, and two young villagers drew the<br />

map again with their own symbols.<br />

Village activities involved:<br />

(a) community meetings to introduce the team and its activities to the village<br />

members, to cover basic in<strong>for</strong>mation on land and <strong>for</strong>est types available,<br />

location of each type (through participatory resources mapping) and categories<br />

of use that people identify <strong>for</strong> each of these landscapes and resources;<br />

(b) personal and small groups interviews to learn about village and land use<br />

history, resource management, level of education, main sources of income,<br />

livelihoods and land utilization system;<br />

(c) focus group discussion on natural resource location, land type identification<br />

by category of uses, people’s perception of <strong>for</strong>ests, sources of products<br />

<strong>for</strong> household consumption and important species <strong>for</strong> different groups of<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mants using the scoring exercise known as ‘pebble distribution method’,<br />

or PDM. PDM was used to quantify the relative importance of land types,<br />

<strong>for</strong>est products and species to local people by distributing 100 pebbles or<br />

beans among illustrated cards representing land types, use categories or<br />

species (Figure 1). In the following tables and figures with in<strong>for</strong>mation from<br />

PDM, the 100% value refers to the total number of pebbles. The pebbles were<br />

distributed by the in<strong>for</strong>mants among the cards according to their importance.<br />

Field activities<br />

The field team consisted of four researchers assisted by one translator, two local<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mants and a field assistant. This team was responsible <strong>for</strong> botany, ethnobotany<br />

and site history data collection. It gathered in<strong>for</strong>mation through direct<br />

observations, measurements and interviews in each sample plot using structured<br />

datasheets.

Figure 1. Scoring exercise (PDM) with Khe Tran men group<br />

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

Activities in the field were decided on and set up in accordance with<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation collected in the village. The field team collected data from sample<br />

plots (Figure 2). The team chose plot locations after the different land types had<br />

been identified by the villagers. Sampling of land types took into account the main<br />

categories of the land types and sites where the most important resources could<br />

be found. Village in<strong>for</strong>mants accompanying the field team provided details on<br />

history and land use of each site, as well as the uses and names of the main <strong>for</strong>est<br />

products that were traditionally collected there. Although the sampling ef<strong>for</strong>t was<br />

distributed across most of the land types, <strong>for</strong>est habitats were given emphasis<br />

since they cover the largest area and generally house more species per sample<br />

than other land types. Most of the land types were sampled with one (rice field,<br />

primary <strong>for</strong>est) or two plots, in total 11 plots were surveyed with 110 subplots.<br />

For each plot a general site description with tree and non-tree data and detailed<br />

ethno-ecological in<strong>for</strong>mation was composed and plot position was recorded with<br />

GPS. Plots consisted of 40 m transects subdivided into 10 consecutive 5 m wide<br />

subunits, where the presence of all herbs, climbers with any part over 1.5 m long<br />

and other smaller plants was recorded. Trees with a diameter at breast height (dbh)<br />

of 10 cm or more were censused and their height and diameter measured using the<br />

same base-transect but variable area subunits (Sheil et al. 2003).<br />

Collaboration between village team and field team was crucial to the collection of<br />

relevant in<strong>for</strong>mation, but collaboration with villagers was also important to link<br />

the data collected by direct measurements with those coming from discussions,

| Methods<br />

Figure 2. Working on sample plot<br />

interviews and questionnaires. Preparation of the final reference list of plants with<br />

their corresponding local-language names took considerable time because of the<br />

mixture of Vietnamese language and Pahy language used by the local people.<br />

Some specimens identified to one species had several local names (e.g. Ageratum<br />

conyzoides) and other specimens with one local name belonged to different species<br />

(e.g. Fibraurea tinctoria and Bowringia sp.). A. conyzoides was given two local<br />

names (Cá hỡi and Sắc par abon) by different in<strong>for</strong>mants at different sites along<br />

with different uses. (Being bad <strong>for</strong> soil, Cá hỡi has few uses, while Sắc par abon<br />

was mentioned as potential fertilizer <strong>for</strong> sweet potato, although another in<strong>for</strong>mant<br />

said that it is actually not used by villagers). Catimbium brevigulatum, which was<br />

recorded in seven plots, had four different local names (A kai, A xây cỡ, Betre,<br />

Papan). Although in<strong>for</strong>mants were reliable and persistent in their ways of naming<br />

species, both gender and different experiences caused variation and the mixture of<br />

different languages (mainly Pahy and Vietnamese) was sometimes confusing <strong>for</strong><br />

the researchers. The ethno-botanical survey was conducted simultaneously in the<br />

field, where we had in total 12 in<strong>for</strong>mants, normally two or more at the same time<br />

with both genders represented. This was important to ensure the broad sampling<br />

of knowledge about uses and sites. As an example, genus Bowringia, which was<br />

present in four plots in two land types (secondary <strong>for</strong>est and primary <strong>for</strong>est), had<br />

no use according to five in<strong>for</strong>mants, whereas two in<strong>for</strong>mants said it was used as<br />

firewood and its roots could be sold.

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

From each plot plant specimens <strong>for</strong> further herbarium identification were<br />

collected. The entire specimen collection has been left with botanist Vu Van Can in<br />

Hanoi. All specimens were conserved in alcohol be<strong>for</strong>e drying and identification.<br />

Some specimens were identified in the field, others later in Hanoi. Genus and<br />

species names follow the nomenclature used in Iconographia Cormophytorum<br />

Sinicorum (Chinese Academy of Science, Institute of Plant <strong>Research</strong> 1972–<br />

1976), Cây cỏ Việt Nam (Pham Hoang Ho 1993), Vietnam Forest Trees (Forest<br />

Inventory and Planning Institute 1996), Yunnan Kexue Chubanshe (Yunnan Shumu<br />

Tuzhi 1990) and the <strong>International</strong> Plant Names Index database (http://www.ipni.<br />

org/); and family names in The plant-book: a portable dictionary of the vascular<br />

plants (Mabberley 1997) and the <strong>International</strong> Plant Names Index database<br />

except Leguminosae sensu lato, which follows the subfamily categorization of<br />

Mimosaceae, Fabaceae sensu stricto and Caesalpiniaceae.<br />

The study in Khe Tran covered two periods, from 15 May to 9 June 2005 and<br />

from 2 to 15 October 2005. The first period was reserved mainly <strong>for</strong> data collection<br />

on the importance of local land types, while during the second period we focused<br />

more on quality control and biodiversity and conservation aspects according to<br />

local people. During both periods, commune officers joined the research team to<br />

make sure that we were safe. Even if their presence was not directly useful to our<br />

research, it was an opportunity <strong>for</strong> researchers to socialize with local authorities<br />

and discuss local perspectives on biodiversity and land types.

. Achievements<br />

During the project, our objectives were to<br />

(a) test and adapt the MLA method as an appropriate mechanism <strong>for</strong><br />

integrating local perceptions and views in decision making and planning.<br />

The method was successfully tested in the rural context of Khe Tran, and even<br />

if the MLA was originally designed <strong>for</strong> assessments of local perceptions and<br />

priorities of <strong>for</strong>est dependant societies in a tropical context, we have shown<br />

here that the method can be adapted to situations where local communities<br />

rely less on the <strong>for</strong>est products than they used to;<br />

(b) provide baseline data that can be used <strong>for</strong> the biodiversity conservation<br />

of the planned Phong Dien Nature Reserve. We have a considerable data<br />

base from our different surveys in Khe Tran, with an amount of important<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation on local priorities and perceptions, on the richness of the vegetation<br />

in the village’s vicinity, on the uses of <strong>for</strong>est and non-<strong>for</strong>est products by the<br />

local people as well as on the economic, social and demographic data of the<br />

village. Seven hundred and fifty-four specimens of plants were recorded,<br />

consisting of 439 species from 108 families, <strong>for</strong> which we registered 824<br />

uses. All these data, including socio-economic data will be valuable <strong>for</strong> the<br />

successful management of the planned nature reserve, providing in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

on the biodiversity in the buffer and core zones, and on the different uses and<br />

valuation of species and of natural resources by the local people;<br />

(c) provide an overview of the importance of landscape and local species<br />

to the people of Khe Tran and collect in<strong>for</strong>mation on their livelihoods<br />

and perspectives on Phong Dien Nature Reserve. Through community<br />

meetings, participatory mapping and scoring exercises, the landscape of the<br />

research area has been studied. Findings reflect the local point of view and

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

relative importance of each category of use. Direct field observations using<br />

systematic sampling supported the recorded local views of the importance of<br />

different species, land types and spatial design of the landscape;<br />

(d) discuss the opportunities and constraints faced by conservation<br />

institutions in the future nature reserve regarding land allocation and<br />

<strong>for</strong>est rehabilitation schemes. Dialogue with local in<strong>for</strong>mants occurred<br />

during the survey, in focus group discussion, interviews and more in<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

discussions, to understand the local priorities and perspectives facing the<br />

future nature reserve planning. A workshop with local people was held at the<br />

end of the survey to discuss the implications of conservation according to<br />

the local point of view, the options <strong>for</strong> local people in the frame of the future<br />

nature reserve, the role they would like to play and the threats to biodiversity<br />

they identified; and<br />

(e) facilitate greater involvement of local people and other stakeholders in<br />

decision making and planning at the local level. Based on survey results,<br />

workshops will be held at the provincial, communal and village levels to share<br />

our in<strong>for</strong>mation and experience with all interested partners, stakeholders and<br />

decision makers, and discussions will be held to look <strong>for</strong> options to involve<br />

local communities in reserve management. Be<strong>for</strong>e these workshops another<br />

part of the project, called Future Scenario, was implemented as a follow-up<br />

of our activity in Khe Tran (Evans 2006). Future Scenario helped the local<br />

community in Khe Tran to build strategies <strong>for</strong> their future based on local<br />

knowledge and preliminary MLA results. A presentation of the local people’s<br />

future scenario was made to the local authorities (commune officers).<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e we analyse the survey results, it is necessary to better understand the<br />

context of conservation in the Phong Dien area and who the villagers of Khe Tran<br />

are.

4.1. Previous conservation activities<br />

Government of Vietnam (GoV) policies have affected the <strong>for</strong>est-related activities<br />

of Khe Tran village. Prior to 1992, the upland <strong>for</strong>est, one of the last remaining<br />

patches of lowland evergreen <strong>for</strong>est including and adjacent to Khe Tran, was<br />

considered a ‘productive <strong>for</strong>est’ and managed by logging companies under the<br />

Department of <strong>Forestry</strong> at the province level. Then in 1992 this site, ‘dominated by<br />

a ridge of low mountains, which extends south-east from the Annamite mountains<br />

and <strong>for</strong>ms the border between Quang Tri and Thua Thien Hue provinces’, was<br />

recognised <strong>for</strong> its ‘important role in protecting downstream water supplies and<br />

reducing flooding in the lowlands of Thua Thien Hue province’ and designated as<br />

a ‘watershed protection <strong>for</strong>est’, a status it still has (Le Trong Trai et al. 2001).<br />

In 1998, international bird conservation groups focused attention on the site<br />

after rediscovery of Edward’s Pheasant (Lophura edwardsi) in these hills, a fowl<br />

thought extinct. Today the site is part of a government <strong>for</strong>est strategy to create a<br />

system of 2 million ha of special use <strong>for</strong>est (national parks, nature reserves and<br />

historical sites) throughout the country and it is listed as one of the sites destined<br />

to become a nature reserve (41,548 ha) in 2010 (Barney 2005).<br />

Local <strong>for</strong>ests around Khe Tran are one of the key biodiversity areas of the<br />

province, since many rare and endangered species of plants and animals can be<br />

found there. Le Trong Trai et al. (2001) report that significant numbers of endemic<br />

and nonendemic plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and butterflies are<br />

found in Phong Dien <strong>for</strong>ests including Khe Tran. Endangered tiger, Panthera<br />

tigris, was confirmed to be present in this area. Muoc, who belongs to the Pahy<br />

ethnic group from Khe Tran, reported that in March 1998 he observed a tiger of<br />

approximately 100 kg at 200 meters from his village. He also reported that in May<br />

1998 a tiger preyed on one of his buffalo in the Moi valley (16°27’N 107°15’E).<br />

He further noticed that, judging by the footprints, two adults and one cub were<br />

present. Villagers also reported during our survey the regular presence of some<br />

of the globally threatened green peafowl (Pavo muticus), although these reports<br />

0<br />

. Conservation context in Khe Tran

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

remain unconfirmed. Some of these key biodiversity species are closely related to<br />

the livelihood of the local people. Our study analyses this kind of knowledge.<br />

First among the threats to <strong>for</strong>est biodiversity identified by BirdLife<br />

<strong>International</strong> and the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute (FIPI) is hunting,<br />

because of the value and rarity of the game, followed by firewood and other nontimber<br />

<strong>for</strong>est product (NTFP) collection, timber cutting, <strong>for</strong>est fires (including<br />

human-made as part of scrap metal collection) and clearance of <strong>for</strong>est land <strong>for</strong><br />

agriculture (Le Trong Trai et al. 2001). But the threats are usually specific to each<br />

site, and detailed in<strong>for</strong>mation is needed <strong>for</strong> each location, as we did in Khe Tran.<br />

In June and July 2001, the nature reserve project team including the project<br />

leader and two local people, in collaboration with the Phong Dien Forest Protection<br />

Department (FPD), conducted hunting surveys in Khe Tran and other parts of the<br />

future Phong Dien Nature Reserve (PDNR). <strong>International</strong> Nature Conservation<br />

made this investigation in the frame of a project named ‘Understanding the<br />

impacts of Hunting on Edwards’s Pheasant Lophura edwardsi at PDNR, Vietnam:<br />

Towards a Strategy <strong>for</strong> Managing Hunting Activities’. Interviews were conducted<br />

with villagers, village leader, hunters/trappers (hereinafter called hunters) and<br />

wildlife traders. Villagers also helped to cross-check in<strong>for</strong>mation obtained in the<br />

field. During the initial meetings with hunters in the future core zone, the team<br />

was accompanied by a local guide. The guide helped to introduce the survey<br />

and emphasized its scientific nature. This helped the socialization of the team’s<br />

activities and to gain local support and trust (see the report in http://www.ruf<strong>for</strong>d.<br />

org/rsg/Projects/reports/Tran_Quang_Ngoc_Aug_2001.doc).<br />

The Protection Area and Development review, in collaboration with the World<br />

Wildlife Fund (WWF), BirdLife <strong>International</strong> and FPD undertook another field<br />

study in Khe Tran and other specific sites of Thua Thien Hue province in late 2001<br />

and early 2002. The objective was to examine the actual and potential economic<br />

contribution of the protected areas to different economic sectors in the province<br />

and to define important policy and planning issues related to maintaining and<br />

enhancing the development benefits from the protected areas. This in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

helped policy-makers and planners to understand how their actions could<br />

influence protected area management, local livelihoods and associated economic<br />

development in the areas. A number of case studies also investigated specific<br />

connections between protected areas and economic sectors (see http://www.<br />

mekong-protected-areas.org/vietnam/docs/vietnam-field.pdf).<br />

A project on Community Participation <strong>for</strong> Conservation Success developed by<br />

WWF, Xuan Mai <strong>Forestry</strong> University and FPD used Khe Tran as one of the training<br />

sites in buffer zones. It was designed to increase the effectiveness of conservation<br />

programs in Vietnam by promoting community participation through communitybased<br />

environmental education (CBEE). The project, started in 2003, aimed to<br />

increase the immediate and long-term capacity of government to incorporate<br />

CBEE training into mainstream training institutions. It also contributed directly to<br />

conservation actions in two priority sites in the Central Annamite, by integrating<br />

CBEE activities into the implementation of protected area conservation projects<br />

(Matarasso and Do Thi Thanh Huyen 2005).

| Conservation context in Khe Tran<br />

4.2. Government programs that affected Khe Tran village<br />

Swidden cultivation was a major activity <strong>for</strong> local livelihoods until 1992–1993,<br />

when most of the households were resettled as part of the government’s fixed<br />

cultivation program. Called ‘327 Program’ (1992–1997), it was the first ef<strong>for</strong>t<br />

of the GoV to develop industrial plantations and to decentralize control over and<br />

reallocate benefit-sharing of <strong>for</strong>est resources in Vietnam (Barney 2005), in line<br />

with the ‘Doi Moi’ economic re<strong>for</strong>m (which, with six major economic changes,<br />

helped Vietnam come out of the economic crisis in 1986). Since then most of the<br />

Khe Tran people have concentrated more on their new agriculture and plantation<br />

land and decreased their activity in the natural <strong>for</strong>ests. In this community, there<br />

was little land suitable <strong>for</strong> wet rice cultivation, and villagers began to cultivate<br />

crops such as maize and peanuts, and to diversify crop production with rubber and<br />

Acacia plantations supported by the national 327 Program.<br />

In 2003, according to Artemiev (2003), new guidelines were <strong>for</strong>med on State<br />

Forest Enterprises (SFE) by various government institutions (see Prime Minister<br />

Decision 187/1999/QĐ-TTg from September 1999 and Political Bureau Resolution<br />

28-NQ/TW of 16 June 2003 on the arrangement, renovation and development of<br />

State Farm and Forest Enterprises), which re<strong>for</strong>med its status to<br />

1. business SFE (<strong>for</strong>estry related business), which earns profits as its main<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance objective and receives no subsidies to cover its operating cost;<br />

2. Protection Forest Management Board (<strong>for</strong>est protection activities), which<br />

combines earned profits and subsidies only <strong>for</strong> cost recovery;<br />

3. other business <strong>for</strong>m (transportation, construction, wood processing,<br />

extension services, etc.), which is similar to business SFE in its objective;<br />

and<br />

4. public utility State Owned Enterprises.<br />

For more than one decade <strong>for</strong>estry activities have been implemented under a<br />

series of national <strong>for</strong>est development programs, most recently the ‘661 Program’<br />

and its predecessor, the 327 Program. In Phong Dien district, the 661 Program<br />

is managed by Phong Dien Forest Enterprise and the management board of Bo<br />

River Watershed Protection Forest (Le Trong Trai et al. 2001). The main <strong>for</strong>estry<br />

activities focused on ‘af<strong>for</strong>esting’ bare lands and degraded areas, and establishing<br />

<strong>for</strong>est plantations. In Khe Tran village, households were paid VND 700,000 to<br />

VND 1 million per hectare <strong>for</strong> planting trees on land allocated <strong>for</strong> plantations<br />

(Acacia spp.). They were then paid a further VND 450,000 <strong>for</strong> the first year and<br />

VND 250,000 <strong>for</strong> each of the next two years under the terms of the <strong>for</strong>est protection<br />

contract (<strong>for</strong> comparison, the average annually per capita income in Khe Tran is<br />

VND 1,944,167). They were not allowed to cut the trees but, in places with older<br />

trees, were allowed to collect fallen branches <strong>for</strong> firewood. In A Luoi district, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, households were paid VND 400 per tree <strong>for</strong> planting cinnamon trees,<br />

which equals VND 4 million/ha (high planting density of Cinnamomum cassia is<br />

10,000 trees/ha; Le Thanh Chien 1996).

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

Further, Le Trong Trai et al. (2001) described that payments from these national<br />

<strong>for</strong>estry programs have provided benefits to villagers in the short term, and Acacia<br />

spp. and pine plantations established under these programs are growing reasonably<br />

well. However, villagers brought attention to a number of problems they had to<br />

face in response to the needs of the national <strong>for</strong>estry programs. For example,<br />

villagers from Khe Tran and Ha Long pointed out that they faced considerable<br />

difficulties after their individual agreement (temporary Land Use Certificate)<br />

on plantation with the Forest Enterprise expired, and they were left without any<br />

further incentive. This kind of agreement does not provide any official recognition<br />

of the local people’s rights to the land, and they only have the right to use the<br />

land, temporarily, <strong>for</strong> the time of the agreement. These same villagers expressed<br />

a preference <strong>for</strong> natural <strong>for</strong>est management approaches that deliver sustainable<br />

and regular benefits and allow them to manage existing <strong>for</strong>est land (including<br />

regenerating <strong>for</strong>est and ‘bare’ lands) in a more sustainable manner.<br />

In Phong Dien district, the main species <strong>for</strong> plantation establishment are<br />

Acacia auriculi<strong>for</strong>mis, Acacia mangium and Pinus kesiya, selected by project<br />

managers of the national <strong>for</strong>estry programs. The total area under <strong>for</strong>est plantation<br />

is substantial: according to Phong Dien Forest Enterprise, 30,366 ha of plantations<br />

have now been established in the three communes of Phong Dien district near the<br />

buffer zone, with support from the 327 and 661 programs. Most plantations have<br />

been established on flat lands and lower slopes, <strong>for</strong> accessibility and financial<br />

reasons.<br />

Rubber trees were also established under the 327 Program in Khe Tran.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, according to Le Trong Trai et al. (2001), this plantation was<br />

established on the river banks, the village’s best lands available <strong>for</strong> agriculture<br />

crops. Because the trees already produce latex, villagers are left without any better<br />

option <strong>for</strong> other agriculture. In our survey we observed that beyond the rubber<br />

plantation and the plain area in the lower part of the village, land is composed of<br />

reddish, stony and hard soil surface.<br />

Le Trong Trai et al. (2001) argued that with an abundance of heavily degraded<br />

land available <strong>for</strong> rehabilitation, <strong>for</strong>est management and other land uses, there is<br />

considerable potential <strong>for</strong> cash earning activities in the buffer zone (<strong>for</strong> example<br />

through economic crop plantations). This activity would also reduce the overall<br />

pressure on the <strong>for</strong>est resources in the nature reserve. They also suggested that<br />

current arrangements <strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>est development and management in the bare lands<br />

are costly, create social tensions and seem to be unsustainable in the long run.<br />

On the other hand some of the Acacia plantations have been established in areas<br />

that are not optimal from environmental or economical perspectives. This practice<br />

may lead to increasing conflicts, especially as land pressure <strong>for</strong> crops continues<br />

to increase. Consideration might, there<strong>for</strong>e, be given to allocating a greater<br />

proportion of existing <strong>for</strong>est lands <strong>for</strong> community management.

| Conservation context in Khe Tran<br />

Summary<br />

Khe Tran village has been through different land use policies. Its <strong>for</strong>ests were<br />

first considered productive <strong>for</strong>ests, then watershed protection <strong>for</strong>ests, and<br />

it is planned to be part of Phong Dien Nature Reserve in 2010, because of<br />

its important biodiversity and the presence of rare and endangered species.<br />

However, <strong>for</strong>ests in the village’s surroundings have been deeply disturbed,<br />

because of war, logging activities and agricultural practices. Many projects<br />

linked to the preparation of the nature reserve have taken place in Khe Tran.<br />

Banning local people from many extractive activities in the planned reserve,<br />

the government has proposed to develop other activities to provide incomes<br />

to all households. In this context, rubber and Acacia plantation programs were<br />

implemented with government support. Even if these programs are supposed<br />

to provide cash income to the local people, some villagers worry about their<br />

future rights on the plantations and expect to get rights to manage the natural<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests and the bare land in a sustainable way. Lack of land <strong>for</strong> agriculture may<br />

become a problem <strong>for</strong> food security and may leave many villagers with few<br />

alternatives to the exploitation of the natural <strong>for</strong>est.

. Site description<br />

5.1. <strong>Research</strong> site<br />

Khe Tran (Phong My commune, Phong Dien district, Thua Thien Hue province) is<br />

situated near the limits of the future Phong Dien Nature Reserve (PDNR) (Figure<br />

3). The village covers an area of about 200 ha and its average elevation is 160 m<br />

asl. Located to the north-west of Hue city, it can be reached by car in 1.5 hours<br />

from the provincial capital. During the rainy season flooding regularly isolates the<br />

village <strong>for</strong> several days. Khe Tran is bordered by the Phong Dien Nature Reserve<br />

on the west and south, and by Hoà Bac village on the east.<br />

The village is in the buffer zone of PDNR, an area of <strong>for</strong>est and converted<br />

lands. The reserve and the village area are dominated by low mountains, which<br />

extend south-east from the Annamite Mountains and <strong>for</strong>m the border between<br />

Quang Tri and Thua Thien Hue provinces. The highest points within the nature<br />

reserve are Coc Ton Bhai (1,408 m), Ca Cut (1,405 m), Ko Va La Dut (1,409 m),<br />

Coc Muen (1,298 m) and Co Pung (1,615 m).<br />

Very little natural <strong>for</strong>est remains in the village vicinity, and plantations cover<br />

an increasing portion of the abundant bare lands. Village houses are scattered on<br />

both sides of a small trail, 1 km from the main road running between Phong My<br />

and Hoà Bac. One characteristic of the village is the isolation of the houses from<br />

each other, and it takes approximately 30 minutes to walk from one end to the<br />

other of this village of 20 households. Home gardens commonly consisting of<br />

pepper and jackfruit are surrounding most of the houses.<br />

This place was chosen <strong>for</strong> our project as the reference site <strong>for</strong> the MLA<br />

activities <strong>for</strong> several reasons:<br />

1. There is a strong presence of a minority group, the Pahy, in the village,<br />

mixed with some Kinh (the majority ethnic group in Vietnam) and Khome<br />

(an alternate name <strong>for</strong> one of the Khmer language groups in Vietnam; see<br />

Gordon 2005). There are 53 ethnic minorities in Vietnam (12.7% of the<br />

population in 1979 census) and some of them have problematic relationships<br />

with the main ethnic group, represented by the central government (Yukio

| Site description<br />

Sources:<br />

- Le Trong Trai et al. 2001<br />

- SRTM 90m Digital<br />

Elevation Data, The<br />

NASA Shuttle Radar<br />

Topographic Mission<br />

- World Administrative<br />

Boundaries, UNEP World<br />

Conservation Monitoring<br />

Centre, 1994<br />

Figure 3. Location of Khe Tran village in the buffer zone of Phong Dien Nature Reserve

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

2001). Generally the main conflicts occur in the Central Highlands (conflicts<br />

over land allocation to Kinh people, problems of traditional land management<br />

and of shifting cultivation), and ethnic minority groups often are not well<br />

perceived by the Kinh. Nevertheless, the GoV has recently made ef<strong>for</strong>ts to<br />

recognize the situation and vulnerability of minority groups and has developed<br />

a policy of integration of these groups into the more global economic life,<br />

through development and infrastructures programs (ADB 2005). We found it<br />

relevant to work with a local community belonging to a minority group that<br />

was already mixed with the main Kinh group. The fact that this community<br />

has been <strong>for</strong>bidden to practice its traditional shifting cultivation activities,<br />

and encouraged to follow the more sedentary mode of agriculture, was one<br />

more reason <strong>for</strong> us to study its perception and priorities <strong>for</strong> natural resource<br />

management, and how it manages its relationships with other village groups<br />

and government authorities at commune, district and provincial levels.<br />

2. A second important reason was the presence of a future nature reserve in the<br />

village’s vicinity. This reserve, decided on after the discovery of Edward’s<br />

Pheasant in the mountains of Phong Dien district, is planned <strong>for</strong> 2010 (BirdLife<br />

<strong>International</strong> et al. 2001) and has great potential <strong>for</strong> local communities’<br />

involvement, although at this time people from Khe Tran and other villages at<br />

the limit of the reserve are <strong>for</strong>bidden to pursue any extractives activity inside<br />

the future core zone. Yet our survey could provide valuable in<strong>for</strong>mation on the<br />

way local people envisage their possible participation in reserve management<br />

and <strong>for</strong> negotiations among all stakeholders.<br />

3. Last, most of the projects in Phong Dien district focus on mines and<br />

infrastructure, while few seek to gain experiences in land use planning<br />

(some projects have developed activities in community <strong>for</strong>estry, but mainly<br />

plantation <strong>for</strong>ests). Results from our activities can be used <strong>for</strong> comparison<br />

with similar projects undertaken in other districts of Thua Thien Hue, or even<br />

other provinces of Vietnam.<br />

5.2. People from Khe Tran<br />

5.2.1. History of the people from Khe Tran<br />

Prior to 1967, Khe Tran village was situated around the upstream portion of the O<br />

Lau and My Chanh rivers (see Figure 4). The villagers practiced shifting cultivation<br />

in this hilly area. They were displaced by war to A Luoi district and even Laos PDR.<br />

In 1971, the GoV in<strong>for</strong>med them that their homeland was safe and that they could<br />

re-occupy it. The village leader and a few other villagers returned to Tam Gianh,<br />

a place situated 2 km from the actual settlement, upstream on O Lau river, and the<br />

remaining refugees followed soon after. The displaced Khe Tran villagers settled<br />

there <strong>for</strong> five years, be<strong>for</strong>e moving on to Khe Cat village, where they remained<br />

until 1978. Finally, they re-occupied their <strong>for</strong>mer homeland, the upstream part of<br />

O Lau river. In 1992, encouraged by the government to settle closer to the main<br />

road, some villagers moved to Khe Tran lowlands (the lower part of O Lau river

| Site description<br />

Sources:<br />

- Department of<br />

Planning and<br />

Investment, TT-Hue<br />

province, 2005<br />

- Landsat Satellite<br />

Imagery Path 125<br />

Row 049, The Global<br />

Land Cover Facility,<br />

2001<br />

- SRTM 90m Digital<br />

Elevation Data, The<br />

NASA Shuttle Radar<br />

Topographic Mission<br />

- World Administrative<br />

Boundaries, UNEP<br />

World Conservation<br />

Monitoring Centre,<br />

1994<br />

Figure 4. Situation of Khe Tran village

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

in the lower part of the village), thus moving away from the lands traditionally<br />

occupied by the Pahy. Most of these villagers were of mixed ethnic origins. This<br />

is how the village became divided into two parts, as mentioned be<strong>for</strong>e, on the<br />

upper and lower reaches of the O Lau river; with support from the government the<br />

villagers living in the lowlands developed agricultural crops (including rice) and<br />

rubber plantations.<br />

5.2.2. Population and ethnicity<br />

One hundred twenty-four villagers, divided into 20 households, live in Khe Tran.<br />

People 15 to 60 years old represent 71% of the population, the remainder being<br />

composed of children (21%) and seniors (8%). Most villagers are farmers and<br />

only a few have other occupations such as police, teacher or tailor.<br />

As mentioned be<strong>for</strong>e, most of the villagers belong to the Pahy ethnic group,<br />

one of the many minority groups found in Vietnam; 23 people are Kinh, which is<br />

the majority ethnic group in Thua Thien Hue province and in Vietnam generally<br />

(Vu Hoai Minh and Warfvinge 2002). There is a single representative of the<br />

Khome ethnic group. Originally only Pahy people inhabited Khe Tran and the<br />

surrounding areas, but with time other ethnic groups have settled in the region<br />

through intermarriages. Pahy and Kinh people live together in both the upland and<br />

lowland village parts.<br />

Interactions between government and minorities like the Pahy are sometimes<br />

strained, especially in respect to land and natural resources rights of usage. Working<br />

with the Pahy of Khe Tran allowed us to study the situation of a minority group <strong>for</strong><br />

which the process of integration and trans<strong>for</strong>mation is practically achieved, and<br />

our observations may be of value as a basis <strong>for</strong> comparison with other groups in<br />

Central Vietnam.<br />

5.2.3. Education<br />

Only eight villagers have not received an education. The villagers who have<br />

received the most years of education are young people (under 30 years old), most<br />

of whom have finished elementary school. A very few have gone to high school.<br />

The sole elementary school is located in a nearby village on the way to the<br />

commune (Phong My). The primary (middle) school is at the commune (5 km<br />

from the village), and secondary (high) schools are located in Phong Dien district.<br />

There was an elementary school in the village, but it closed <strong>for</strong> lack of students.<br />

Most of villagers hope <strong>for</strong> better education, infrastructure and institutions.<br />

They think that education can help them to increase their welfare by providing<br />

their children with useful knowledge and skills.<br />

5.2.4. Livelihood<br />

Villagers of Khe Tran work most of the time in their rice fields, in their home<br />

gardens (mostly growing pepper and jackfruit) and in rubber and Acacia plantations

0 | Site description<br />

as a result of the government resettlement program. Despite these new sources<br />

of income, people still occasionally gather <strong>for</strong>est products (e.g. honey, rattan)<br />

and war wreckage from the nature reserve. Some villagers still depend on nature<br />

reserve <strong>for</strong>ests, but an increasing number of people depend on more permanent<br />

agriculture and plantation <strong>for</strong> their livelihoods and <strong>for</strong> cash earning. Villagers in<br />

the lowlands principally depend <strong>for</strong> their livelihoods on cultivation of seasonal<br />

crops, plantations, livestock and home gardens, whereas those in the uplands are<br />

relying on plantations and livestock (Figure 5).<br />

Figure 5. Livestock and Acacia plantations are important in Khe Tran<br />

Some important events have affected the livelihoods of the villagers. Until<br />

recently, the inhabitants of Phong Dien districts, including Khe Tran village, had<br />

to cope with problems of flooding, drought and <strong>for</strong>est fire. For example, floods<br />

caused widespread damage to crops and infrastructure in 1983 and 1999. During<br />

the 1999 floods, houses, crops and even lives were lost in Khe Tran. Widespread<br />

fires and drought were also reported in the district in 1985, and another drought<br />

occurred in 1990. We recorded these events which started from 1992, when some<br />

villagers started to settle in the lower part of the village (Table 2).<br />

5.2.5. Source of income<br />

There is a big difference between the two parts of the village in terms of household<br />

income (Table 3). According to the household survey, people from the lower part<br />

have a higher annual income (average of VND 13.7 million) than those from the

Table 2. Important events affecting the local livelihoods<br />

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

Year Disasters/important events Causes<br />

1992 Settlement in Khe Tran village Following government plans<br />

1993 Forest assigned to villagers Because previous <strong>for</strong>est management by<br />

the government failed to prevent <strong>for</strong>est<br />

destruction, <strong>for</strong>ests were assigned to local<br />

people (re<strong>for</strong>estation program). This helped<br />

the local people to use the bare lands, which<br />

are still officially included in the <strong>for</strong>est<br />

category<br />

1999 Flood Natural disaster which damaged/destroyed<br />

some houses<br />

2003 Access to electricity Government program<br />

2004 Access to water <strong>for</strong> irrigation<br />

(self-running water system)<br />

Government program <strong>for</strong> poverty alleviation<br />

upper area (VND 9.6 million). The average household contains six members, with<br />

an income of VND 1.6 million to VND 2.3 million per capita. These values are<br />

much lower than the general per capita income in Vietnam of USD 553, or VND<br />

8.7 million in 2004 (http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/4130.htm). We found that<br />

some households’ income was below the poverty line of VND 1.04 million per<br />

capita (Vietnam General Statistical Office at http://www.unescap.org/Stat/meet/<br />

povstat/pov7_vnm.pdf#search=’poverty%20line%20in%20vietnam’).<br />

Rubber (Figure 6) and Acacia plantation, livestock, home gardens and<br />

retirement subsidies are the main source of income <strong>for</strong> the lower area, while Acacia<br />

plantations and war subsidies (compensation) represent the main source <strong>for</strong> the<br />

upper part. People from the upper part have little cash income from livestock,<br />

rattan, home gardens and the collection of war wreckage.<br />

Some of the villagers were in the army during the war against the USA, and<br />

they still receive compensation from the government. Two villagers have opened<br />

small shops that sell drinks and foods. The owners lay in supplies at the market of<br />

Phong My commune. Some villagers work in Phong Dien as teachers and police<br />

officers, and one is a tailor in Ho Chi Minh City.<br />

Villagers living in the upper part are near the natural <strong>for</strong>est and use it when<br />

they experience food shortages. Food security is critical in the upper part as they<br />

do not cultivate rice and <strong>for</strong> cash income depend on Acacia plantation. Ef<strong>for</strong>ts to<br />

intensify livestock and home garden production may help to improve their income<br />

and to secure food availability. Maltsoglou and Rapsomanikis (2005) reported that<br />

livestock plays an important role in household income in rural areas of Vietnam.<br />

Acacia plantation is a potential source of substantial income <strong>for</strong> households<br />

nowadays and may become even more important in the future. Demand <strong>for</strong> local<br />

Acacia production is significant and absorbs all harvested products in Khe Tran.<br />

Demand from pulp and chipboard factories located near Thua Thien Hue and the<br />

GoV program to expand the plantation area (Barney 2005) bode well <strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>est<br />

plantation as a means to increase local income. Plantation may also provide fodder<br />

<strong>for</strong> livestock.

| Site description<br />

Table 3. Income range by source of products and settlement area<br />

Source of income<br />

Household income (VND millions)<br />

Lower area Upper area<br />

Monthly Annually Monthly Annually<br />

Rubber plantation 0.27–0.67 3.20–8.00 0.00 0.00<br />

Acacia plantation 0.58 7.00 0.10–0.25 1.20–3.00<br />

Livestock 0.25 3.00 0.10–0.29 1.20–3.50<br />

Home garden 0.58 7.00 0.25 3.00<br />

Pension 0.61 7.30 0.60 7.20<br />

Agriculture n.a. n.a. 0.10 1.20<br />

Rattan 0.05 0.60 n.a. n.a.<br />

War wreckage 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.20<br />

Store 0.00 0.00 0.05–0.58 0.60–7.00<br />

Others 0.17 2.00 0.03–0.15 0.30–1.80<br />

Average 1.14 13.70 0.80 9.63<br />

Range 0.35–2.08 4.2–25 0.33–1.67 4–20<br />

n.a. means respondents gave no in<strong>for</strong>mation in regard to the small amount of income obtained from<br />

corresponding source<br />

Figure 6. A woman from the lower part of the village harvests rubber from her<br />

plantation

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

Another opportunity to increase and diversify income is to utilize the river <strong>for</strong><br />

fish production. O Lau river, near the village, is approximately 20 m wide and in<br />

some parts has natural pools that offer potential <strong>for</strong> fish farming. Fisheries have<br />

been introduced and are popular in other areas of Phong Dien and A Luoi districts<br />

(Le Trong Trai et al. 2001) and may also prove useful in this village, even if there<br />

are great concerns in case of flood and about dioxin contamination of the river.<br />

5.2.6. Access and interaction with outsiders<br />

Access to the commune is good, with a 4 m–wide path linking the village to the<br />

main road of the commune. Villagers use bicycles and motorbikes to go to the<br />

commune. During the rainy season, however, sections of the path are sometimes<br />

cut by floods, especially in the lower parts. The village road becomes muddy and<br />

slippery. A bridge connects the lower and upper parts of the village, and a bigger<br />

bridge is under construction with assistance from the Thua Thien Hue Rural<br />

Development Project (Appraisal Mission 2004).<br />

Outsiders interacting with villagers are traders who buy agricultural products<br />

(peanut, pepper, rubber, cassava) or sell meat and clothes. Sometimes villagers<br />

meet outsiders who collect eaglewood, war wreckage or rattan, but there is little<br />

interaction. The coffee shops in the upper part of the village are the place where<br />

villagers frequently chat with outsiders.<br />

Villagers reported that many extension workers from government and<br />

nongovernment institutions have held training courses in the village since the<br />

program of land allocation and re<strong>for</strong>estation started in the early 1990s. They<br />

think that these extension ef<strong>for</strong>ts have been very useful and hope to have more<br />

workshops especially on technical and management aspects of livestock, plantation<br />

and agriculture.<br />

5.3. Land use and natural resources<br />

In the village’s vicinity the planned nature reserve and its buffer zone consist of<br />

patches of degraded <strong>for</strong>est, grassland, Acacia and rubber plantations, and areas<br />

reserved <strong>for</strong> agriculture. Two main rivers can be found near the village, the O Lau<br />

and My Chanh rivers.<br />

During our first observations and community meetings, we identified the<br />

main surrounding land types, e.g. alluvial plain with settlements, pepper gardens,<br />

rubber plantations, rice fields and other dry-land agriculture, hilly areas with<br />

secondary <strong>for</strong>ests, Acacia plantations, settlements, pepper gardens and grasslands.<br />

We recorded about 20 different land types identified by the villagers around Khe<br />

Tran (Table 4). The land type identification reflects the official perception and<br />

classification of land tenure (e.g. land reserved <strong>for</strong> settlement, land <strong>for</strong> peanut<br />

farming), along with some features less relevant to our activities (e.g. waterfall,<br />

small road, bridge).<br />

We tried, there<strong>for</strong>e, to classify the local perception, rather than the official<br />

one, and the land types were regrouped into six main types, namely bare hills,

| Site description<br />

Table 4. Identified land types in Khe Tran<br />

Land types (Pahy) Description<br />

Cutect vườn Land <strong>for</strong> garden<br />

Cutect màu Land <strong>for</strong> agriculture<br />

Cutect a tong Land <strong>for</strong> peanut farming<br />

Cutect along Land <strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>est plantation<br />

Cutect vá Land <strong>for</strong> cemetery<br />

Cutect cho tro Land <strong>for</strong> rice farming<br />

Cutect tiêu Land <strong>for</strong> pepper farming<br />

Cutect cao su Land <strong>for</strong> rubber farming<br />

Cutect âm bút Land <strong>for</strong> natural <strong>for</strong>est<br />

Cutect cỏ Land <strong>for</strong> grass/bare land<br />

Đa pưh Pahy Pahy/O Lau river<br />

Đá so tù moi Tu moi tributary<br />

Cutect ta xu Land <strong>for</strong> houses<br />

Ân yên cooh 935 Mountain peak of 935<br />

A chuh Rana Rana waterfall<br />

Chooh Rana Sandy area of Rana riverside<br />

Mỏ zeeng Gold mine<br />

Along papứt Big tree <strong>for</strong>est<br />

Along cacet Small tree <strong>for</strong>est<br />

Câm foong fứt Bridge<br />

dry land <strong>for</strong> agriculture, <strong>for</strong>ests, home garden, rice field and rivers. The <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

classification was further divided into plantation, small tree and big tree <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

(see Table 5).<br />

O Lau river is an important part of the landscape near the village. It traverses<br />

the entire village territory, close to the settlements. The second big river, My<br />

Chanh river in the northern part of Khe Tran, is rarely used by the local people.<br />

Forests within and around the village are categorized into three types as<br />

mentioned above. Plantation <strong>for</strong>ests in our survey include Acacia and rubber.<br />

The oldest (8 years) rubber plantation of the village is situated near the main<br />

road, and covers about 10 ha, including some patches of new plantations. The<br />

Acacia plantation begins in the middle of the village and reaches to the upper part,<br />

covering about 160 ha. Small tree <strong>for</strong>est represents the dominant types of <strong>for</strong>est<br />

around the village, mainly inside the Phong Dien Nature Reserve, and consists<br />

of young Myrtaceae and Rubiaceae <strong>for</strong>ests. Big tree <strong>for</strong>est (or primary <strong>for</strong>est) is<br />

distant from the village, situated at more than one day’s walk, inside the reserve<br />

area.<br />

Bare lands (Figure 7) were caused historically by war, fires, grazing and<br />

shifting cultivation (Le Trong Trai et al. 2001). This land type, dominated by<br />

shrubs and grasses, is the target of re<strong>for</strong>estation ef<strong>for</strong>ts by the government. Acacia<br />

plantations are developed on these bare hills.<br />

The rest of the village’s landscape is divided into settlements, home<br />

gardens (pepper and fruits), bare hills, rivers and roads. If land <strong>for</strong> plantation is<br />

geographically specialized (Acacia in the upper part and rubber in the lower part),<br />

home gardens can be found near the houses in both parts of the village.

Table 5. Regrouped land types in Khe Tran<br />

Biodiversity and Local Perceptions |<br />

Land types (<strong>English</strong>/Pahy) Description<br />

Home garden/Cutect vườn Mostly pepper with jackfruits and pineapples;<br />

around houses<br />

Land <strong>for</strong> agriculture /Cutect màu Peanut and cassava; lower part of Khe Tran<br />

Rice field/Cutect cho tro Dry rice field<br />

Bare land/Cutect cỏ North of the village; shrub and grass on hills and<br />

riverbanks<br />

River/Đa pưh South and north of the village (O Lau and My<br />

Chanh rivers)<br />

Forest plantation/Cutect along Rubber and Acacia<br />

Small tree <strong>for</strong>est/Along ca cut Young regrowth around village<br />

Big tree <strong>for</strong>est/Along papứt West of the village (far from the village)<br />

Figure 7. Considerable areas of bare land are used in Khe Tran <strong>for</strong> new Acacia<br />

plantation<br />

Khe Tran landscape mainly reflects the ef<strong>for</strong>ts of the central government to<br />

manage the local community resettlement and to apply agricultural and <strong>for</strong>estry<br />

programs through land allocation schemes. This mosaic landscape dominates<br />

the village area near the settlements. They are situated on alluvial plains, which<br />

represent the best land.<br />

The GoV has pursued a land use policy that has greatly influenced the<br />

development of Khe Tran. With the objective of creating a natural reserve at Phong

| Site description<br />

Dien, the government has encouraged villagers to abandon traditional agriculture<br />

and other activities in the mountains <strong>for</strong> permanent agriculture in the rich lowland<br />

soils. The government is omnipresent in the activities of villagers through the<br />

Provincial People’s Council, which frequently intervenes at the local level. The<br />

people’s council of the Phong My commune is involved in all decision-making<br />

concerning daily village management, nominates the village chief and decides the<br />

attribution of government-financed development projects.<br />

Our in<strong>for</strong>mers said that they did no longer hunt in the <strong>for</strong>est because there is<br />

little game and hunting is banned by the government. This said, when shown a<br />

map, they can tell where to find the different wild animals, which shows that they<br />

have only recently given up hunting or that some clandestine hunting (mostly by<br />

snares as firearms are illegal) still occurs.<br />

An old cemetery is situated in the middle of an Acacia plantation, and the<br />

remains of abandoned villages can be found around the small tree <strong>for</strong>est in the<br />