Sixty years separate us from the birth of rock’n’roll – and slap bang in the middle of that is the event that marked rock’n’roll’s passage into respectability. The programme on sale at Live Aid called the event a “global jukebox”.

At its most effective, this is exactly what it was. No one puts money in a jukebox with the intention of playing a record they’ve never heard before, and the cleverest artists who performed that day realised this was no time to shift new product.

Given one song early in the day to rescue his flagging fortunes, Adam Ant sang his next single Vive Le Rock and effectively signed his own death warrant. Bryan Ferry was similarly short-sighted, choosing to perform three songs out of his allotted four from his new Boys & Girls album (the other was his cover of Jealous Guy) over his most fondly remembered Roxy Music hits.

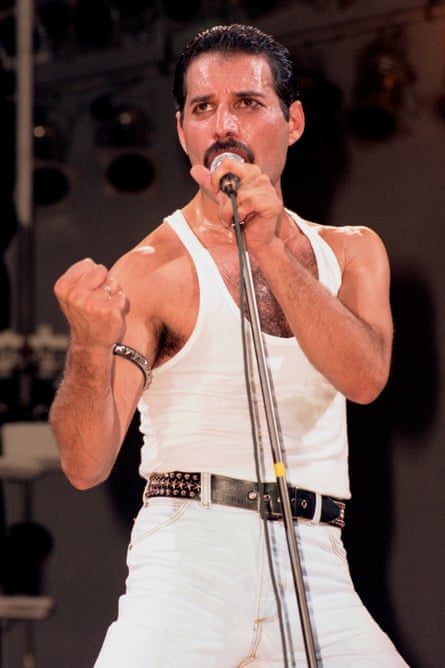

And, of course, at the other extreme, no one played it smarter than Queen, who somehow managed to crowbar six hits into their 20-minute slot. This was no accident. As their drummer, Roger Taylor, said at the time: “It’ll make a pot of money for a wonderful cause, but make no mistake, we’re doing it for our own glory as well!”

The following week’s chart positions ratified their new status. Queen’s Greatest Hits, The Works and Mercury’s solo album Mr Bad Guy soared up the charts; the following summer they returned to Wembley for a headlining show of their own.

Before Live Aid, they wouldn’t have dared presume they could fill such a space, but the events of 13 July ushered in a new kind of mega-rock event in which there appeared to be no losers: television coverage helped drive sales; a generation of music fans raised on canonical rock artists had the disposable income to spend on these happenings; and the bands, benefiting from the extra coverage, got more and more popular. Ensuing shows by Simple Minds, Genesis, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd and U2 meant Wembley was being used almost as much for music as it was for sport.

By helping create a new superleague of rock stars, an event conceived purely to raise money for African famine victims ended up generating just as much revenue for the labels to whom the artists were signed. From the industry’s perspective, the timing was perfect. Compact disc players were becoming affordable and the format gave baby boomers the perfect excuse to forego new music in order to re-purchase albums by many of the artists who performed that day.

With this in mind, it’s no surprise that, in the intervening years, the music industry has been desperate to relive Live Aid – a major live pop event, usually charitable, that reinforces the status of established artists and anoints a handful of new ones. Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday, Freddie Mercury’s tribute concert, Live 8, Live Earth, Concert for Diana are all cases in point.

At the age of 60, rock’n’roll finds itself in a strange position. What was once countercultural has now inevitably become the status quo. No fixture on the calendar represents that delicate transition quite like Glastonbury. The festival which, according to the editor of fRoots magazine and inaugural attendee, Ian Anderson, started out as “just one stage, a bunch of hippies, with free milk handed out from the farm”, now caters to two audiences. Up in the Green Fields, it’s much the same as it always was: dozens of stages play host to troupes of bearded self-styled self-sustaining artists playing music whose commercial potential is as negligible as it was 40 years ago.

On the main stage, where the BBC cameras are trained, it’s a different story. Lionel Richie is playing his hits to 200,000 people whose desire to experience a moment of musical togetherness radiates outwards into the sitting rooms of middle England, in the process giving Richie a No 1 album and further ratifying Glastonbury’s place in the cultural fabric of Britain. Without the paradigm shift set in action by Live Aid, it’s hard to imagine any of that happening.

- This article was amended on 13 July 2015. The “f” was removed from fRoots magazine during the editing process. This has been corrected.