Satvinder Jandu, senior project manager, British Museum

It’s hard to imagine now, but the courtyard at the centre of the museum used to look like a mini Manhattan. It was cramped with multilevel concrete buildings that housed the book stacks for the British Library. They were joined by walkways at different levels, and an internal labyrinth of corridors. Demolishing this whole structure was the riskiest and most complicated part of the whole project – they turned out to be much better built than anyone had expected.

People think of the roof as the defining image of the Great Court, but it’s just the icing on the cake. There was a huge subterranean development to create the education centre, and the scope of work extended right to the front gates, with new landscaping of the forecourt, as well as new galleries to the north. Some fascinating finds were made during the excavations, from the foundations of the old Montagu House building [where the museum first began in the 1700s], to lots of old clay pots.

One key concept was how the Great Court would act as a public thoroughfare through Bloomsbury, open to visitors beyond the usual gallery hours. The entrance was a real bottleneck. It was not a pleasant experience to be there on a Saturday with 10,000 people trying to get into the museum. You arrived in an underwhelming space with a dark and dingy corridor leading to the reading room.

The construction took 33 months but we didn’t close the museum to the public for a single day. A real low point was when we discovered that our supplier had switched the stone for the south portico fromPortland stone – which was specified in the contract and which matched the original – to a more creamy coloured French limestone. We had no idea until the finished blocks started arriving on site. It hit the press, but it was too late for anything to be done. The roof was already being assembled, and the portico had to be ready to receive the roof structure. If we had delayed, the whole project would have ground to a halt for 18 months and we would have missed the millennium deadline.

After much deliberation , we decided to proceed with the alternative stone, which is geologically the same: the seam goes from Portland, down the English Channel and then appears in the middle of France. Its colour has mellowed over time.

The impact of the project was transformational – not just for visitors, but also for staff. It elevated the whole institution to another level. There are still some occasional niggles today. The acoustics in the Great Court are not particularly good and it can be problematic if you’re holding large functions or concerts in it. And the way the building is serviced is quite complex, because of how things had to be weaved in and out of the old structure. Twenty years on, we’re having to replace some of the equipment.

Over the years, tastes change and people tend to take a different view about buildings, but the Great Court is timeless and remains largely untouched from how it was conceived.

Spencer de Grey, head of design, Foster + Partners

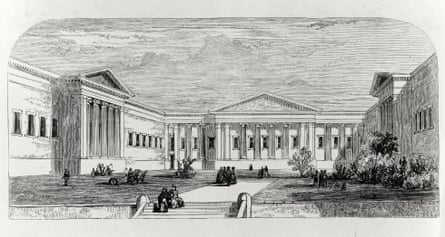

Sir Robert Smirke’s 1823 masterplan for the British Museum created a magnificent courtyard at its heart. However, it only lasted a few years before a new library, designed by Smirke’s brother Sydney, was built in its midst – the Round Reading Room – and the rest of the courtyard was then submerged under lean-to book stacks. It was a lost space waiting to be rediscovered, an opportunity finally triggered 150 years later by the move of the British Library to a new building at St Pancras.

Our first recommendation in the architectural competition was to remove the empty book storage buildings and open up the original courtyard, raising its floor to the same level as the entrance to the museum. Integral to this was the painstaking restoration inside and out of the round reading room, with its dome that is bigger than St Paul’s. We retained the original fittings, the tables and bookcases, and reinstated the original Victorian decorative scheme for the dome: pale blue and gold.

The symmetry of the original courtyard, with its four mighty classical porticos, had been undermined when the southern portico was demolished in the late 19th century to make way for more accommodation. We all felt that it was important to reinstate it, but the approach to this and its detailing, whether historic or contemporary, was much debated. Ultimately, we agreed to honour Smirke’s original design.

The biggest challenge was the new glass roof, whose geometry had to reconcile the asymmetrically placed, circular reading room with the rectangular courtyard. We started with a more traditional, flat-trussed design, but then developed an arched, shell-like structure that would allow carefully controlled natural light into the courtyard. We worked with the University of Bath and Buro Happold, who were developing new CAD technology, and created a gently curved glass roof with 3,312 triangulated individual glass panels.

I vividly remember the final stages of its erection and the shared sigh of relief when the two separate halves of the steel structure met precisely on the join line, all to within 3mm accuracy. My daughter, and that of the then chief executive of the museum, were given the honour of clambering on the erection deck on to the roof and placing in position the final pane of glass.

Below the courtyard we built the African galleries and a new lecture room. The cast iron structure of the adjacent 150-year old reading room meant the excavation around it was extremely sensitive. Working in an historical setting is always difficult – there are so many unknowns – and I was woken up one morning to be told that movement had been detected in its framework which was of concern. But we were able to quickly confirm that it met the tolerances specified, and work was able to continue.

Nearing completion, the museum’s chairman of the trustees announced that he wanted to use the new lecture room before completion for a talk by a special guest. The air-conditioning system was not commissioned, nor were all the doors fixed. Anxiety levels increased 10-fold when we were told that the special guest was Nelson Mandela. He gave a memorable speech to a capacity audience. We had never been so glad when the event ended without a hitch.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion