With the threat of nuclear war creeping back into our minds since Russia's invasion of Ukraine last February, many people are worried about where would be best to hide from a nuclear blast.

A new study published in the journal Physics of Fluids has calculated where in a building might be safest to shelter in the case of a nuclear bomb being detonated nearby.

Assuming that the building isn't inside the initial fireball of the blast, in which everything and everyone would be vaporized, the main danger other than radiation is the massive blast wave that comes after the explosion. The study found that the best place to shelter is in a sturdy building at the far end of the room from any door or window, and ideally in a corner.

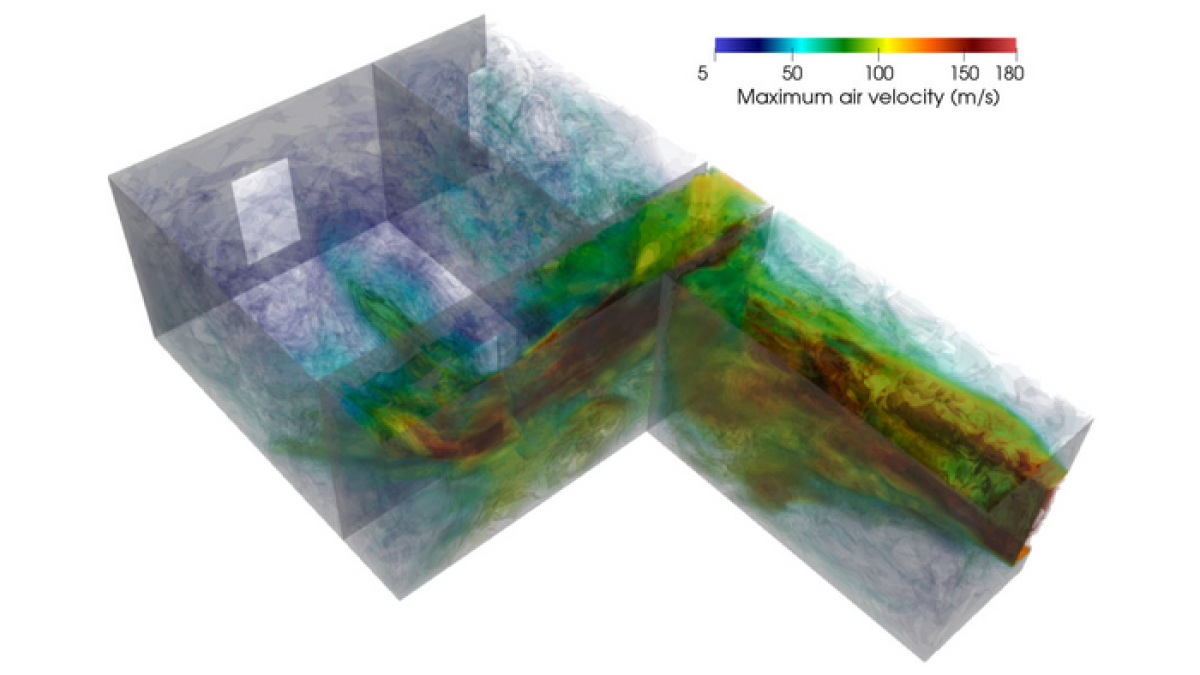

The study authors, from the University of Nicosia in Cyprus, used advanced computer modeling to investigate how a 750-kiloton—around three times as powerful as Nagasaki's "Fat Man" in Japan in 1945—nuclear blast wave and the high-speed winds that follow move through a building, and how strong the forces are throughout a room.

They found that the air speed can actually increase as the blast wave enters a room through a window or door. The wave has a peak windspeed outdoors of roughly 163 mph at 5 psi overpressures (the sudden onset of a pressure wave after an explosion caused by the release of energy), while indoors, these can peak at about 411 mph from the same pressure blast.

Additionally, the air speeds can be further accelerated as they travel down narrow hallways. These high winds and blast forces can lift a person off the ground, causing them to fall or be slammed into walls, which is the fatal factor.

"The most dangerous critical indoor locations to avoid are the windows, the corridors, and the doors," co-author Ioannis Kokkinakis said in a statement. "People should stay away from these locations and immediately take shelter. Even in the front room facing the explosion, one can be safe from the high airspeeds if positioned at the corners of the wall facing the blast."

Of course, this depends on the building itself being sturdy enough to withstand the blast. Many buildings would be destroyed by the shockwave. A survivor would have only a few seconds between seeing the nuclear bomb explode and finding shelter before the air blast arrived.

For those in cities, better places to shelter would include underground spaces, Jack L. Rozdilsky, an associate professor of disaster and emergency management at York University in Canada, told Newsweek.

"One would be much safer if they could get to an underground purpose-built blast or fallout shelter," he said. "Even locations like basements of buildings or deep sections of subway tunnels would provide better protection than being in buildings above the surface. While many variables are involved when considering the impacts of nuclear weapons on cities, for those not killed in the initial blast, the shock wave produced from the explosions would be extremely harmful.

"Considering the shock wave alone, dangers in cities from the shock wave of a nuclear blast would include high-speed winds turning objects into projectiles that penetrate the body, the human body being thrown into objects, crush injuries from structure collapse, and potentially various forms of barotrauma [or injuries due to increased air pressure] like damage to body tissue and ruptured ear drums."

The collision of two ships in Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1917 gave some idea of how a shockwave can decimate a city. One of the ships was carrying hazardous cargo, and after the collision, the cargo exploded in what was the largest explosion on the planet at the time, Rozdilsky said. The shock wave leveled about 2 square kilometers, or around 500 acres, of the city. About 2,000 people were killed and 9,000 injured, many by shattered glass.

"Civil defense from nuclear war remains problematic as in many cities' viable underground sheltering options are non-existent for the public," Rozdilsky said.

"For example, given Russian nuclear threats in Ukraine, assessments are rapidly taking place to find suitable underground sheltering locations for population protection during a nuclear attack. In the event of a nuclear attack, radiological emergency, current civil defense guidance instructs North American city dwellers to 'get inside', 'stay inside' and to 'stay tuned' to the news."

Ultimately, the best place to survive a nuclear blast is outside a major city, not just because the countryside is less likely to be targeted but because the natural topography provides more shelter from a shockwave blast.

"I am of the view that a rural area which is not downwind of an obvious target is the best place if you want to avoid fallout and other effects of the bomb. A good place would be a valley where the hills would give you some protection from heat and blast from bombs which go off [miles] from where you are," Mark R. Foreman, an associate professor at Chalmers University of Technology in Göteborg, Sweden, previously told Newsweek.

However, those safe from the blast would then be at the mercy of the radioactive fallout, which can reach a lot farther away from the blast site, and can be carried in the water in weather systems.

"For those outside the cities and not experiencing the direct effects of blast and immediate radiation, they will need to be aware of the weather conditions if within 30-40 miles of the target, as wind can quickly blow radiation clouds that rain over the land within a few hours," Paul Ingram, a senior research associate at the University of Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, told Newsweek. "Radiation levels further afield will rise too, in a longer term."

So the absolute safest place to be in the case of a nuclear blast would be as far away as possible, with mountains and hills to protect against the blast wave and block rainy weather.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about nuclear blasts? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

References

Kokkinakisa, I. W., and Drikakisb. D. Nuclear explosion impact on humans indoors. Physics of Fluids, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0132565

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.