Important Cultivated Grasses

Important Cultivated Grasses

by C.V. Piper, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1915

INTRODUCTION

One can readily learn to recognize many of the grasses, both cultivated and wild. It is not necessary to have any elaborate instruments for examining them or to acquire any detailed knowledge of their structure. Nearly every grass is so distinctive that once a person has noted its obvious characteristics he will easily recognize it again. Though there are probably 6,000 distinct species of grasses in the world, only about 60 are important cultivated plants, and not more than 20 wild species are abundant or valuable in any one locality.

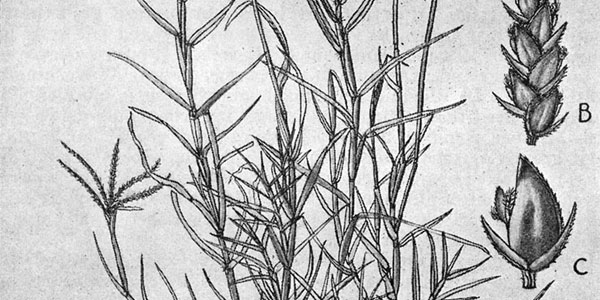

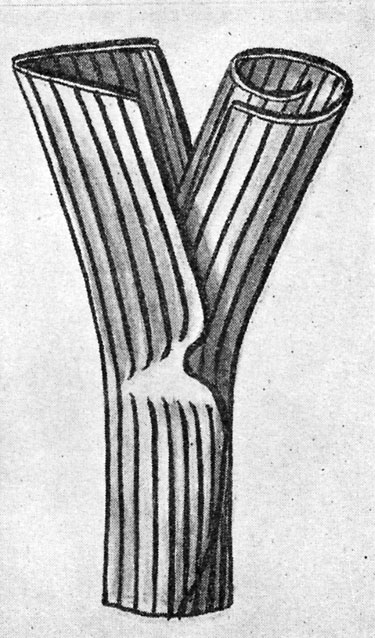

Grasses are easily distinguished from all other plants by several peculiar characters. The roots of all, whether annual or perennial, are slender and threadlike. The stems are jointed, usually cylindrical and commonly hollow, but solid in such species as corn and sorghum. In the bamboos and a few other grasses they are woody. The joint is called a node, and the part between the nodes is an internode. The leaves are usually long and narrow, parallel veined, and are attached at the nodes, first on one side, then on the other, so that they are in two ranks. The lower part of the leaf encircles the stem as a sheath, while the upper portion, the blade, is more or less flattened. In some grasses the blades are folded, in others inrolled in the bud. (Figs. 1 and 2). Where the blade and the sheath join, the texture and color are usually different, this joining part being called the collar. Each free angle of the collar sometimes bears a projection called an auricle. (Fig. 3) On the inner side of the collar most grasses have a delicate flap, the ligule. (Fig. 3) The forms of the ligules, as well as of the auricles where present, vary greatly in different grasses, so that most grasses can be identified by the structures about the collar. The lower internodes of a grass stem are very short, and in consequence the basal leaves are more or less crowded. The higher internodes are usually much elongated and unequal, but in some grasses, like corn and bamboos, they are nearly equal in length. In a grass that branches below the flower cluster, the branch always arises from the base of an internode in the angle of the leaf sheaf. The flower clusters of grasses exhibit a great many forms, and many grasses may be at once recognized by the forms of these clusters. Each branch appears from the base of an internode, but, for the most part, leaves or rudiments of leaves do not occur in the flower cluster.

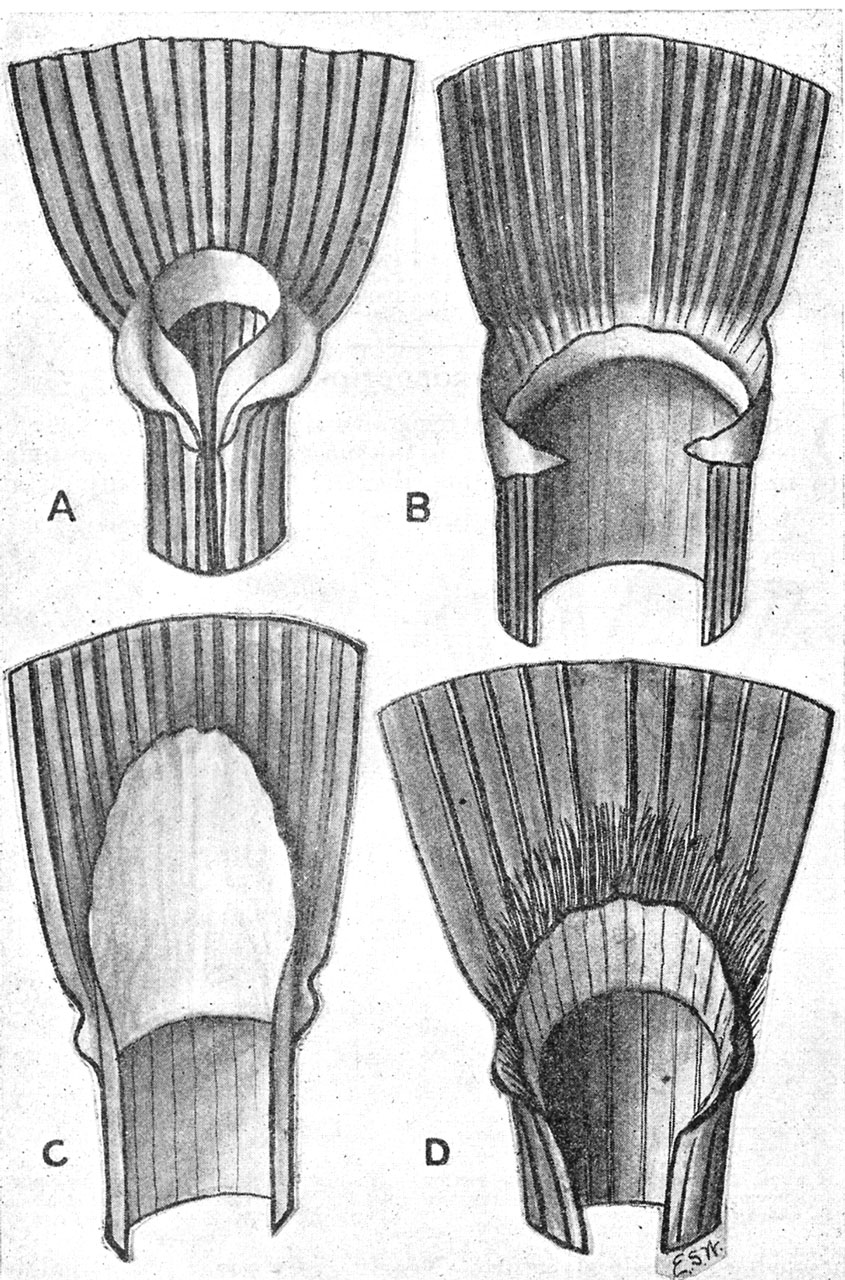

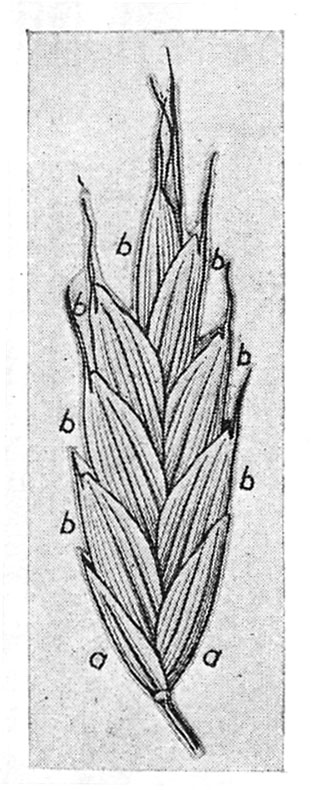

The flowers of grasses are borne in spikelets, which may be many-flowered, as in cheat (Fig. 4), or single-flowered, as in timothy. (Fig. 5) The individual flowers are enclosed in scales, which are modified leaves. The two basal scales are called glumes; each of the other evident scales is a lemma, often bearing an awn from the back or top. A spikelet of timothy (Fig. 5) shows these various parts dissected. In Figure 5, A, the two glumes at the base are shown; in Figure 5, B, these are removed, disclosing the lemma, and opposite it another scale, the palea. When the lemma and palea are removed there are seen opposite the palea two minute scales, the lodicules (Fig.5, C), which by becoming swollen serve to open the flower. The flower proper consists of a pistil with the ovary at the base and two feathery stigmas; surrounding the pistil are three stamens, each with a slender stalk or filament and the terminal anther bearing pollen. The spikelets of all grasses are based on the same pattern, the members differing mainly in size and form.

TIMOTHY

Timothy (Phleum pretense L.; Fig. 6) is the most important hay grass cultivated in America. The extent of its culture is three times as great as that of all other cultivated hay grasses, and slightly larger than the combined hay acreage of alfalfa and the clovers. Timothy has long been the standard hay in American markets, particularly for horse feed. Its reputation as a feed depends upon its high palatability and slightly laxative effect, combined with moderate nutritive value, so that it is practically impossible to injure an animal by overfeeding. Timothy had become the most important hay grass in the United States as early as 1807, and it has until recently held this position unchallenged. Timothy is one of the best known of all grasses and is not likely to be confused with any other. In Europe there are 11 closely related grasses, one of which, the mountain timothy (Phleum alpinum), is also native to North America, occurring from Alaska to Greenland and southward to the mountains of California, New Mexico, and New England. It has been thought by some that timothy itself is native to North America, but as it surely is not indigenous to Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, or the region north of New England, it is now generally conceded that it is an introduced species.

Timothy is well adapted to the northern half of the United States and somewhat farther southward in the mountains. The southern limit of its successful culture is approximately the same as the northern limit of cotton culture. To the northward it will produce well and survive the winters practically up to the Arctic Circle. Timothy differs in one respect from most other grasses in that one (sometimes two) of the lower internodes is swollen into an ovoid body, referred to as a “bulb” or “corm,” but in reality only a thickened internode. Each one of these “corms” is annual in duration, forming in early summer and dying the next year when the seed matures. Timothy consists of many different strains, so that there are large possibilities of improvement by selecting the most desirable forms. Already much has been done along this line to produce improved varieties.

Weight of seed of timothy per bushel – 45 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 1,200,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 9 to 12 pounds

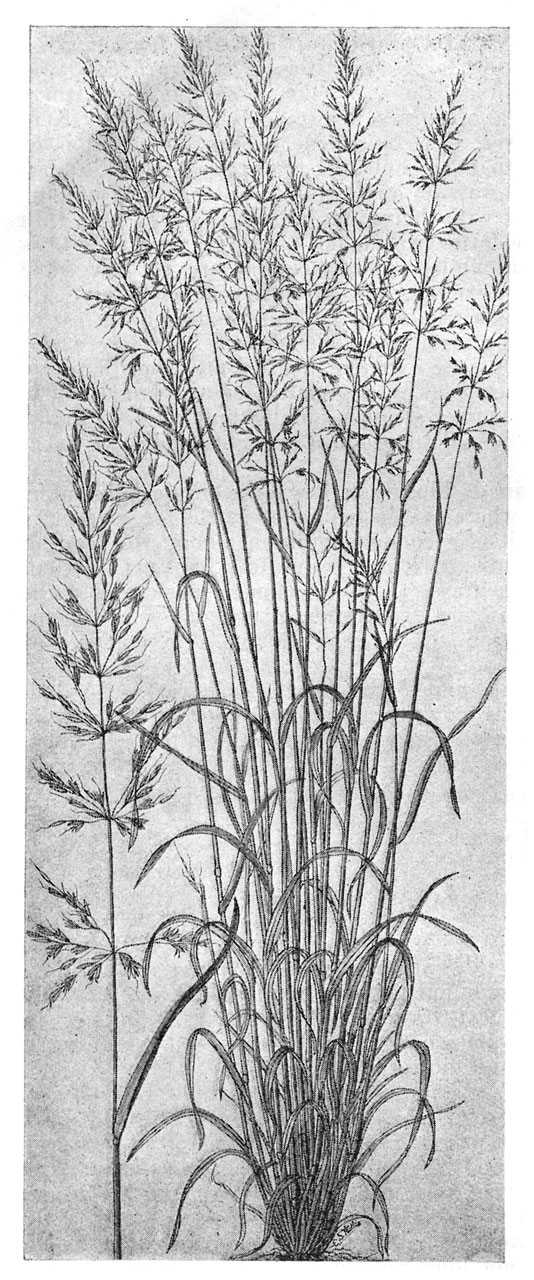

KENTUCKY BLUEGRASS

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L; Fig. 7) is, with the possible exception of timothy, the most noted grass in North America. Perhaps on account of the famous bluegrass country in Kentucky the opinion prevails that this grass is a true native. Such, however, is not the case, and bluegrass did not grow in Kentucky when Boone discovered that attractive region. Like most of our best cultivated grasses bluegrass is a native of the Old World, where it occurs naturally over much of Europe and Asia. It was brought over by the early colonists as one of the species contained in mixed grass seeds, and, like some of the others, found the soil and climatic conditions congenial. The name bluegrass has been supposed to be due to the purplish color of the flowers, but there is good evidence that the name was first applied to Canada bluegrass, which has bluish foliage, and was later transferred to the really green plant now called Kentucky bluegrass.

Kentucky bluegrass is well known for the beautiful lawns which it makes, as well as for the highly nutritious pasturage which it furnishes. It occurs throughout the northern half of the United States, except where the climate is too dry. In the mountains and on the Pacific coast lowlands it extends farther southward.

Seed of Kentucky bluegrass is harvested mainly in Kentucky, but more or less in Missouri, Iowa, and Nebraska. Special stripping machines are used in harvesting, after which the seed must be dried carefully, so as to prevent heating, which seriously weakens its germination.

Kentucky bluegrass has creeping underground stems, each bearing a tuft of leaves at the tip. Unlike some other grasses Kentucky bluegrass blooms but once each season. When not in bloom it can usually be recognized by the leaves, which are V-shaped in cross section, and by the peculiar leaf tip, which resembles the bow of a boat.

Bluegrass is a favorite lawn grass in the North and is also the principal pasture grass on all rich soils. It has been supposed to have a special liking for limestone soils, but recent investigations indicate that this is not primarily on account of the lime, but because of the general richness of such soils. It is an abundant grass on all good soils, whether rich in lime or poor in that substance.

Most bluegrass pastures are not sown to this grass, but dependence is usually placed in the practical certainty of this grass appearing spontaneously in all good pasture lands.

While true bluegrass is not native to North America, very closely related plants occur in Alaska and in Anticosti Island.

Weight of seed of Kentucky bluegrass per bushel – 14 pounds

Fancy recleaned – 19 to 28 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 2,200,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 14 to 18 pounds

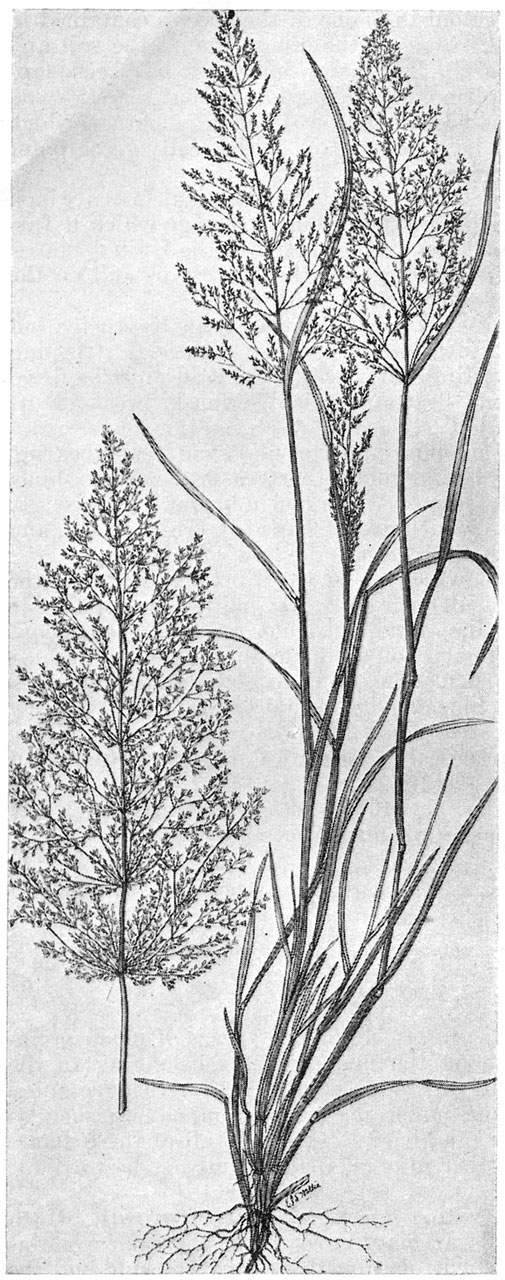

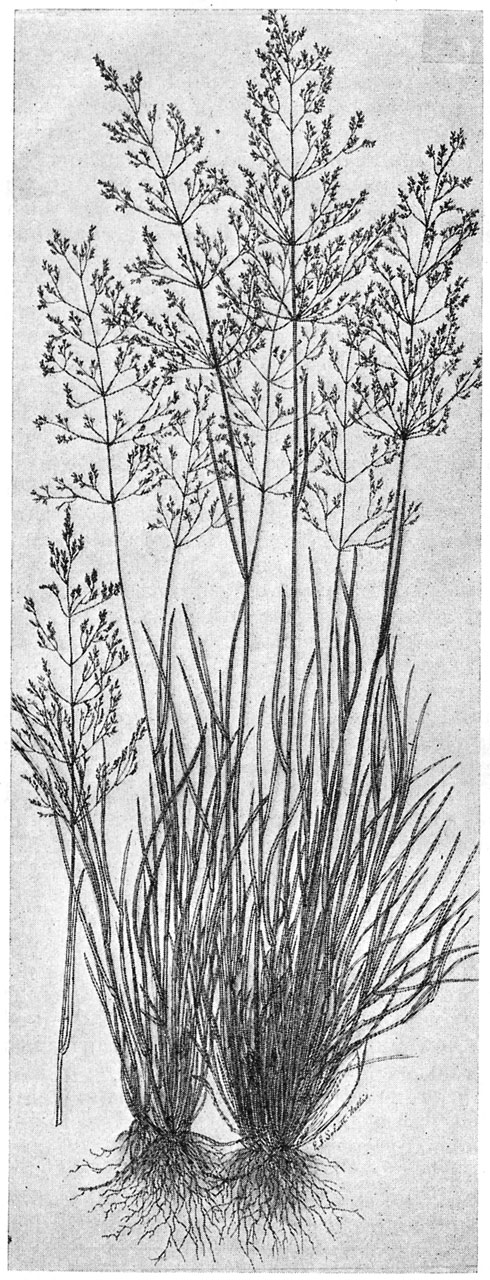

REDTOP

Redtop (Agrostis alba L.; Fig. 8) is the only grass of much prominence as a hay plant among the many grasses belonging to the genus Agrostis. It was early introduced into the American colonies. This grass has been known under many common names, such as whitetop, fiorin, white bent, and herd’s grass. As all of these names belong more properly to other grasses, they should not be used for redtop.

It is a perennial grass, with a creeping habit of growth, which makes a coarse, loose turf. It matures at about the same time as timothy. The leaves are about one-fourth of an inch wide and the stems slender. The loose, pyramidal, usually reddish panicle is very characteristic.

No other grass will grow under as great a variety of conditions as redtop. It is the best wet-land grass among the “tame” species. It will grow on soils so very poor in lime that most other grasses fail. It is the best wet-land grass among the “tame” species. It will grow on soils so very poor in lime that most other grasses fail. It is strongly drought resistant and is often used for holding banks to prevent erosion. Redtop is second only to bluegrass as a pasture plant in the northeastern part of the country. It is a vigorous grower and will form a good turf in a short time. It is found from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, and from New York to California. Though often used in lawn mixtures, its use by itself as a lawn grass is not to be recommended. It will add to the yield of a timothy and clover hay crop, but is considered objectionable by buyers of market hay.

The chief uses of redtop are (1) as a wetland or sour-land hay crop; (2) as a part of pasture mixtures under humid conditions, especially on soils other than limestone; (3) as a soil binder; and (4) as an ingredient in all hay mixtures which are to be fed at home.

Most of the seed of redtop is produced in southern Illinois. The seed is smaller than that of any other commercial grass and for that reason should be comparatively free from impurities, as it is easily separated from other seeds by screening. It is sold in two grades, known as chaffy and recleaned. The latter should be purchased, as it is more economical, and there is less danger of its containing noxious weed seeds.

On account of its small seed, redtop should have a fine, mellow seed bed, and care should be taken to prevent covering it too deeply in the soil. It may be seeded either in early spring or late summer. When seeded alone 8 to 10 pounds of good seed to the acre will insure a stand. From 4 to 5 pounds are sufficient when used with other grasses for hay, and 2 to 3 pounds are enough to use in pasture mixtures, as it spreads quite readily under favorable conditions.

Weight of redtop seed per bushel:

Chaffy – 14 pounds

Recleaned – 30 to 48 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 5,000,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 8 to 10 pounds

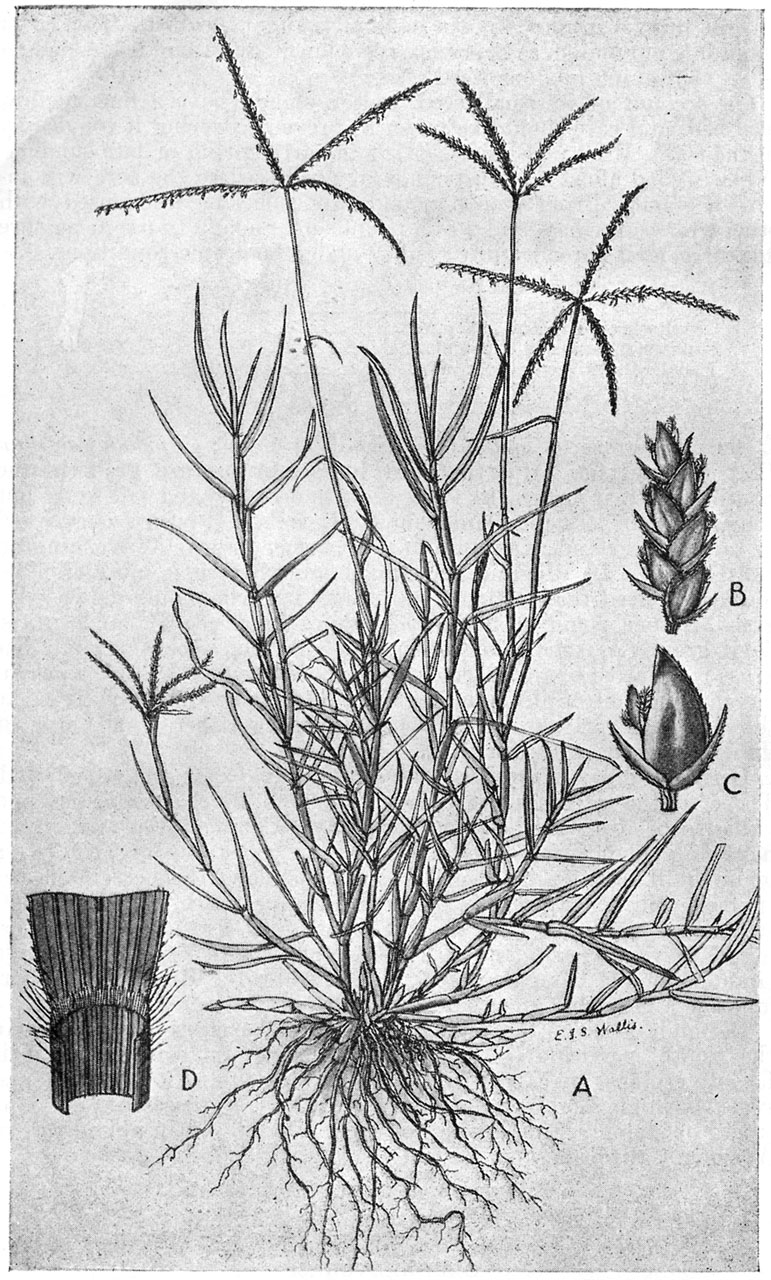

BERMUDA GRASS

Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers.; Capriola dactylon (L.) Duntze; Fig. 9) is the most important pasture grass in the South, where it makes its best growth on clay and silt soils but grows more or less abundantly on sandy soils. It occurs north ward as far as Maryland, Kansas, and the warmer valleys of Washington and Oregon. In Virginia and Maryland, where it is more troublesome as a weed than valuable as forage, it is commonly called wire grass. Other common names sometimes used are Bahama grass, devil grass (Arizona and California), and dog’s-tooth grass. The grass is a native of the warmer portions of the Old World, where it has many names in different regions. It became well established in the south as early as 1807, probably coming either from India or the Mediterranean region.

Bermuda grass is very variable and many forms can be selected. Three of the varieties are different enough in characteristics and value to be distinguished agriculturally. Common Bermuda grass has white underground jointed stems or rootstocks as large as a goose quill, besides the leafy stems or stolons that creep on the surface. St. Lucie grass is identical in appearance, but lacks rootstocks and rarely survives the winter north of Florida. Giant Bermuda is very coarse and has abundant rootstocks. The Florida Giant Bermuda has pale-green foliage, while the Brazil Giant Bermuda is a rich blue green and agriculturally more valuable.

Bermuda grass is the plant most used for pastures and lawns in the South, particularly on clays and loams; on sandy soils it is largely replaced by carpet grass. In humid regions it produces seed very sparingly and so is commonly planted by pieces of the rootstocks or stolons. Good seed, however, is produced in abundance in Arizona, California, and Australia.

Weight of seed of Bermuda grass per bushel – 35 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 1,800,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 5 pounds

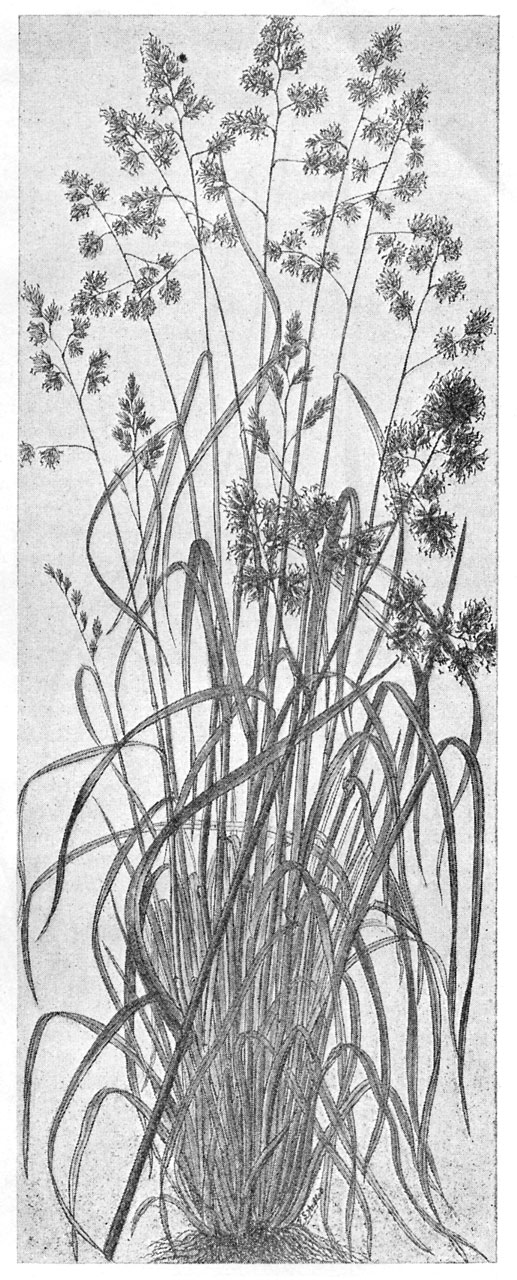

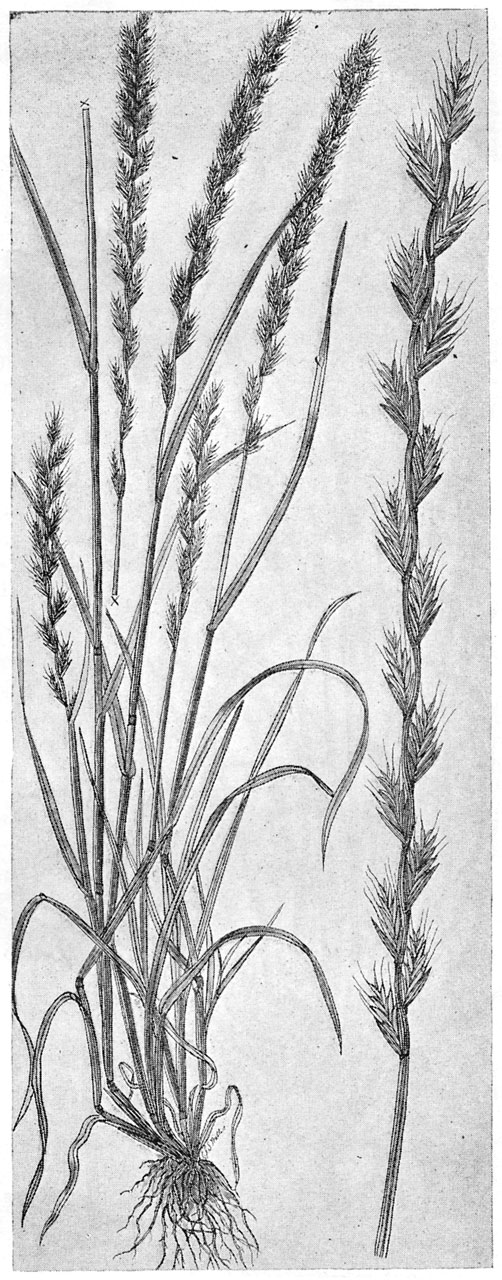

ORCHARD GRASS

Orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata L.; Fig. 10) is a well-known standard grass which is grown to some extent in nearly every State in the Union and quite commonly in the region east of the Mississippi River and north of Alabama and Georgia. It attains most importance, however, in Kentucky, southern Indiana, Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland, and seems thoroughly adapted to a variety of soils in these States. It was first cultivated in Virginia in 1760, although the grass is a native of Europe.

Orchard grass is readily distinguished by its large circular bunches, folded leaf blades, and compressed sheaths, and by the peculiar form of its flower heads. The shape of the head has suggested the common English name of cocksfoot. Its ability to grow in the shade of trees is responsible for the name orchard grass.

Orchard grass possesses certain objectionable features, which have greatly interfered with its popularity in the general region where timothy can be successfully grown. These features are mainly its bunchy habit and the tendency of the hay which it produces to be woody, especially when it is not cut at the proper stage of maturity.

In large cities at the present time there is practically no market for any grass hay except timothy, and the demand for orchard-grass hay is only local and very limited. In the timothy region orchard grass is looked upon unfavorably, but where timothy can not be grown successfully it is used to quite an extent and is considered of very good quality. If the seed is sown at the rate of about 2 bushels per acre, so that it makes a thick stand, the quality of the hay will be much improved. Its value is also increased by the addition of red clover or alsike clover, and where it is grown with tall meadow oatgrass or meadow fescue its quality seems to improve. In some localities such mixtures have become important. To obtain the best results for hay it should be cut when it is just in bloom, as at that time the quality seems to be the best and the yield is at the maximum. The hay is fairly good feed for horses, but it is more valuable for cattle, especially for fattening them for the market.

For pasture, orchard grass gives the best results when mixed with other grasses and clovers and is of special importance from the fact that it grows early and late in the season.

Seed of orchard grass is produced to the largest extent in Jefferson, Oldham, and Shelby Counties, Ky., Clark County, Ind., Loudoun and Fauquier Counties, Va., and in some of the counties adjoining these in the States mentioned. In the sections just referred to the average yield of seed is 10 to 12 bushels per acre.

Weight of seed of orchard grass per bushel – 14 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 600,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 12 to 20 pounds

CARPET GRASS

Carpet grass (Axonopus compressus (Swartz) Beauvois; Fig. 11) is also known as Louisiana grass and by the Creoles of Louisiana as petit gazon. It is a perennial creeping grass, forming a dense, close turf, easily distinguished by the compressed 2-edged creeping stems rooting at each joint, and by the blunt leaf tips. In the United States the grass has never become troublesome as a weed. It is a native of the West Indies but is now widespread in the Tropics of both hemispheres. It was introduced into the United States prior to 1832 and is now abundantly established on the coastal plain soils from southern Virginia to Texas, extending inland to Arkansas and north-central Alabama. It is especially adapted to sandy or sandy loam soils, particularly where the moisture is near the surface most of the year. On such soils it will occupy the land in practically pure growth, especially under heavy continuous grazing. The flower stems grow to a height of 1 foot, or rarely 2 feet, and are very slender. Even where the grass is grazed heavily good crops of seed are produced, as livestock graze principally on the basal leaves.

Over much of the area in which it grows carpet grass is more valuable than any other perennial grass yet known for permanent pastures. It continues growing throughout most of the year, being damaged only during periods of severe drought or of heavy frost. With sharp frosts the leaves turn yellow, but nevertheless cattle continue to graze on the browned grass. It is probable that the carrying capacity of carpet grass under favorable conditions is as great as that of bluegrass, namely, about one head to 2 acres, but in exceptional cases one head to an acre. To maintain pastures in good condition heavy grazing is necessary, and the alternate grazing of two fields is preferable to the continuous grazing on a single field. On the soils most favorable to carpet grass it makes up a very large proportion of the total grazing afforded. It is rare to find carpet grass and Bermuda grass growing on the same soil area. Lespedeza, or Japan clover, however, succeeds very well when mixed with carpet grass. Bur clover and Augusta or narrow-leaf vetch are also valuable in carpet-grass pastures and once established reseed themselves each year.

For its best development carpet grass requires both abundant heat and moisture and under such conditions may be pastured from May to November, or in the extreme South even longer. During the cool weather of winter it makes little growth. If, however, a field of carpet grass be allowed to grow tall in the fall, cattle will graze eagerly on grass in the winter.

Carpet-grass seed is harvested mainly in Mississippi and Louisiana, and the seed is of good quality.

Weight of seed of carpet grass per bushel – 18 to 36 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 1,350,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 5 to 10 pounds

CANADA BLUEGRASS

Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa L.; Fig. 12) is a hardy perennial grass, producing an abundance of creeping rootstocks by which it forms a close turf. It rarely attains a height of more than 24 inches, usually growing from 6 to 8 inches high. It is dark blue in color and resembles Kentucky bluegrass, to which it is related. The characteristics readily distinguishing this grass from the latter are its compressed stems, which long remain green, the single shoot at the end of each rhizome, and the close, narrow panicles.

Canada bluegrass was introduced from Europe and is now found commonly throughout almost the entire Kentucky bluegrass region, especially in the New England States, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. In Canada it is very important, especially in the southern part of Ontario, in the region bordering on Lake Erie. In this section large quantities of seed are produced and exported to the United States. Under most conditions there is no doubt that Canada bluegrass is decidedly inferior to Kentucky bluegrass. However, it is by no means worthless and is of much more importance than agricultural writers ordinarily admit.

Canada bluegrass will grow on any kind of soil that will support Kentucky bluegrass and will thrive on some stiff clays and thin gravelly soils where the latter will make but little growth. It is decidedly aggressive, and under conditions that are not favorable for Kentucky bluegrass it excludes the later almost completely. It’s value is almost entirely as a pasture grass, since it does not grow to a sufficient height to give a profitable yield of hay. The hay which it does produce, however, is of excellent quality and considered by horsemen much better than timothy, especially for race horses. The hay is very heavy and requires a much smaller bulk than ordinary hay to make a ton. It is said to produce a slightly laxative effect when fed to stock.

As a pasture grass Canada bluegrass possesses considerable value. In western New York, where the fattening of cattle for market is an important industry, it is a common opinion among the leading stockmen that good pastures of it are better for this purpose than pastures of Kentucky bluegrass. These stockmen consider it to be much more nutritious than the latter when grown under conditions such as exist in that section It is also valuable as a pasture for dairy cows.

For lawns and golf links and similar purposes it can be used to advantage under conditions too dry and otherwise not entirely favorable to Kentucky bluegrass in mixtures with the latter. It must, however, be kept closely clipped.

Weight of seed of Canada bluegrass, per bushel – 14 to 24 pounds

Fancy recleaned – 18 to 24 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 2,500,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 20 to 30 pounds

TALL MEADOW OATGRASS

Tall meadow oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius (L.) Beauvois; Fig. 13), sometimes called tall oatgrass, meadow oatgrass, and evergreen grass is a hardy perennial growing to the height of 30 to 60 inches and producing large tufts or bunches. It produces seed in an open head, or panicle, somewhat similar to cultivated oats, though the seed is much smaller and more chaffy.

Tall meadow oatgrass is a standard grass in parts of Europe and is grown quite generally over the United States, but it has not attained great importance in any locality. This is perhaps largely due to the fact that the seed is expensive and that it takes a large quantity per acre to secure a stand. Aside from this, the grass, though succulent, has a peculiar taste which stock apparently do not relish until they have become accustomed to it. It is probable that this quality would not long remain a serious drawback to the growing of the grass, as abundant experience proves it to be palatable and highly nutritious.

Tall meadow oatgrass prefers well-drained soil and seems to be especially adapted to light sandy or gravelly land. It does not grow well in shade. It can be used for either pasture or meadow, and when grown for the latter purpose it gives a heavy yield of hay. It should be cut about the time of blooming.

This grass gives the best results either for pasture or meadow if sown in a mixture with other grasses, especially with orchard grass. A mixture of it with red clover, alsike clover, and orchard grass is often grown and is a good one, as all of these plants mature at the same time.

Tall meadow oatgrass seems to stand pasturing well and furnishes an abundance of grazing. It comes on early in the spring and remains green until late in the autumn. These points are greatly in its favor.

Its poor seed habit is one of the greatest drawbacks to the popularity of tall meadow oatgrass, for while it produces seed in sufficient quantity the seed shatters off before it is fully mature, making it very difficult to harvest. The seed is also of low vitality, and difficulty is experienced in securing a stand.

Ground on which this grass is to be sown should be plowed thoroughly some time before seeding and well settled by means of a roller, drag harrow, or similar implement. Just before the seed is sown the surface of the ground should be stirred well with a disk harrow. On account of the character of the seed the best results will be obtained by sowing broadcast, as the seed does not feed evenly through a drill. With the grade of seed now in the market it is necessary to use from 30 to 50 pounds per acre if sown alone.

Seed is produced to a limited extent in Virginia, but most of it is imported from Europe.

Weight of seed of tall meadow oatgrass per bushel – 10 to 16 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 150,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 30 to 40 pounds

MEADOW FESCUE

Meadow fescue (Festuca elatior L.; Fig. 14), also called English bluegrass and, in the South, Randall grass, is a hardy perennial grass attaining a height of 15 to 30 inches, or even more on rich land. It does not propagate by rootstocks or form a very heavy sod, neither is it inclined to be so bunchy as orchard or tall meadow oatgrass. Its leaves are bright green and very succulent. The seed is produced in abundance in open panicles, similar to Kentucky bluegrass, although much larger and more easily harvested. It is a standard grass in Europe, but has not received the attention which is due it in this country. It is grown to a very limited extent in some portions of the New England States, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky and on a very small scale in a few of the Southern States. It is of most importance in eastern Kansas and Nebraska and in parts of Missouri.

Seedsmen distinguish tall fescue as Festuca elatior and meadow fescue as F. pratensis, but these are merely tall and medium varieties of the same species. The former is more valuable, but the seed is scarce and expensive.

Meadow fescue is useful as a pasture grass, and it makes a very good quality of hay and gives a fair yield. On average land 2 tons per acre is not exceptional, and it is possible to produce even more than this under proper treatment. Where the hay is used it is considered of very good quality, but it is nowhere grown in large quantities. Meadow fescue does not reach its highest state of productiveness as quickly as timothy but usually persists much longer. In sections where it is most common it has thus far been grown for seed and pasture rather than for hay. It is a very valuable grass for pasture, as it comes on early in the spring and also remains late in the fall. The latter point is of especial importance in Kansas and in Nebraska, as it supplements the native pastures. For wet soils few grasses are equal to meadow fescue. After the frost has killed the native grasses, stock may be pastured on meadow fescue, thus reducing by several weeks the period of dry-lot feeding.

Meadow fescue has excellent seed habits and produces an abundance of highly germinable seed, which is easily harvested and cleaned. Northeastern Kansas is at present producing more seed than any other section of the country, and seed from this source gives a good stand of grass without difficulty.

Weight of seed of meadow fescue per bushel – 22 to 24 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 225,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 30 pounds

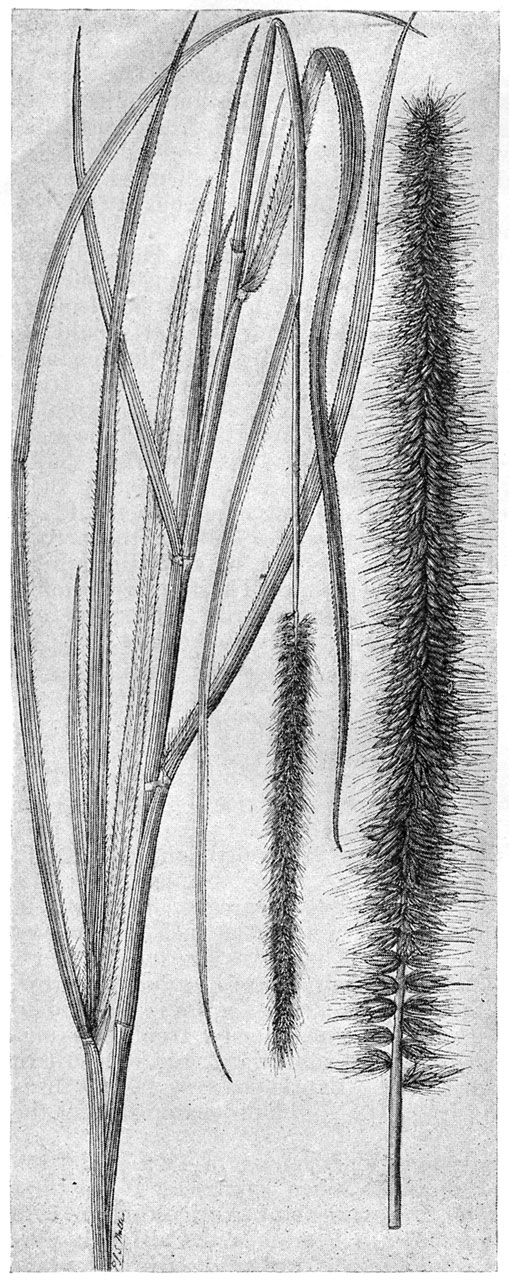

FOXTAIL MILLET

Foxtail or Italian millet (Setaria italica (L.) Beauvois; Chaetochloa italica (L.) Scribner; Fig. 15) is a plant of very ancient cultivation, far antedating the records of written history. Many varieties now exist, some of the principal ones being German, common or Golden Hungarian, Siberian, and Kursk millets. Hungarian millet is also called Hungarian grass. Originally millet was cultivated as a cereal for food, and its use for this purpose is still extensive. In America, however, it has been used almost wholly for forage, both hay and pasturage. The cultivated forms of foxtail millet are not known to occur wild, but are believed to have developed from the nearly related wild green foxtail (Setaria viridis (L.) Beauvois).

Millet is a summer or warm-season short-lived annual. It is able to grow and mature with relatively small supplies of moisture and is therefore largely grown in dry regions. On account of its rapid growth it is much used as a summer catch crop.

Millet hay is considered good feed for cattle, but has long been regarded as injurious to horses, causing derangements in the kidneys, swellings of the joints, and softening of the bones. The best hay is obtained by cutting the plant in early bloom.

Millet has the reputation of seriously reducing the yield of the crop that follows, which does not add to its popularity with farmers.

Weight of seed of foxtail millet per bushel – 48 to 50 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 200,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 30 pounds

RHODES GRASS

Rhodes grass (Chloris gayana Kunth; Fig. 16) is a perennial plant, native t South Africa, first cultivated by Cecil Rhodes in South Africa about 1895. It is fine stemmed, very leafy, and grows to an average height of about 3 feet. The flowering head consists of long spreading spikes, 10 to 15 in a cluster. Seed is produced in abundance. The grass also spreads by means of running branches 2 to 6 feet long, which root and produce a tuft at every node. At no place in the United States has it become troublesome as a weed. Rhodes grass is completely destroyed when the temperature in winter falls to about 18 degrees F., and as a perennial grass it is therefore adapted only to Florida and a narrow strip along the Gulf coast to southern Texas and westward to southern California. Farther north it must be treated as an annual. At Washington, D. C., it will produce but a single crop of hay in a season. Farther south two cuttings may be obtained under favorable conditions. On rich land in central and southern Florida, however, as many as six or seven cuttings are made in a single season. A good stand of Rhodes grass will yield from 1 ¼ to 1 ½ tons of hay to a cutting from an acre. This hay is of very fine quality and is eagerly eaten by horses and cows.

Seed of Rhodes grass is at present all imported from Australia, where the grass is extensively grown. There seems to be no reason, however, why seed should not be produced in the United States, especially in view of the demand and the excellent quality of the seed which has been grown in test plots.

Early spring seeding usually gives the best results. The seed bed should be prepared by thorough plowing, after which the subsurface should be well settled by the use of a roller or similar implement. Just before the seed is sown the surface layer of soil should be loosened and well fined. This can be done by light disking and harrowing when the ground has become somewhat packed from rains, but if the surface has not packed or crusted harrowing is sufficient. On account of the comparatively low viability of the seed, 10 pounds per acre are necessary, and, since it is somewhat chaffy in nature, broadcasting by hand is generally more satisfactory than the use of mechanical seeders. After sowing, the seed should be covered lightly with a weeder if available or a spike-tooth harrow. If the soil is not reasonably rich, the addition of a fertilizer high in available nitrogen is frequently profitable. The fertilizer should be applied preferably after the grass begins growth. If used before this time its strength is dissipated to a considerable extent.

Weight of seed of Rhodes grass per bushel – 8 to 12 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 1,700,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 10 pounds

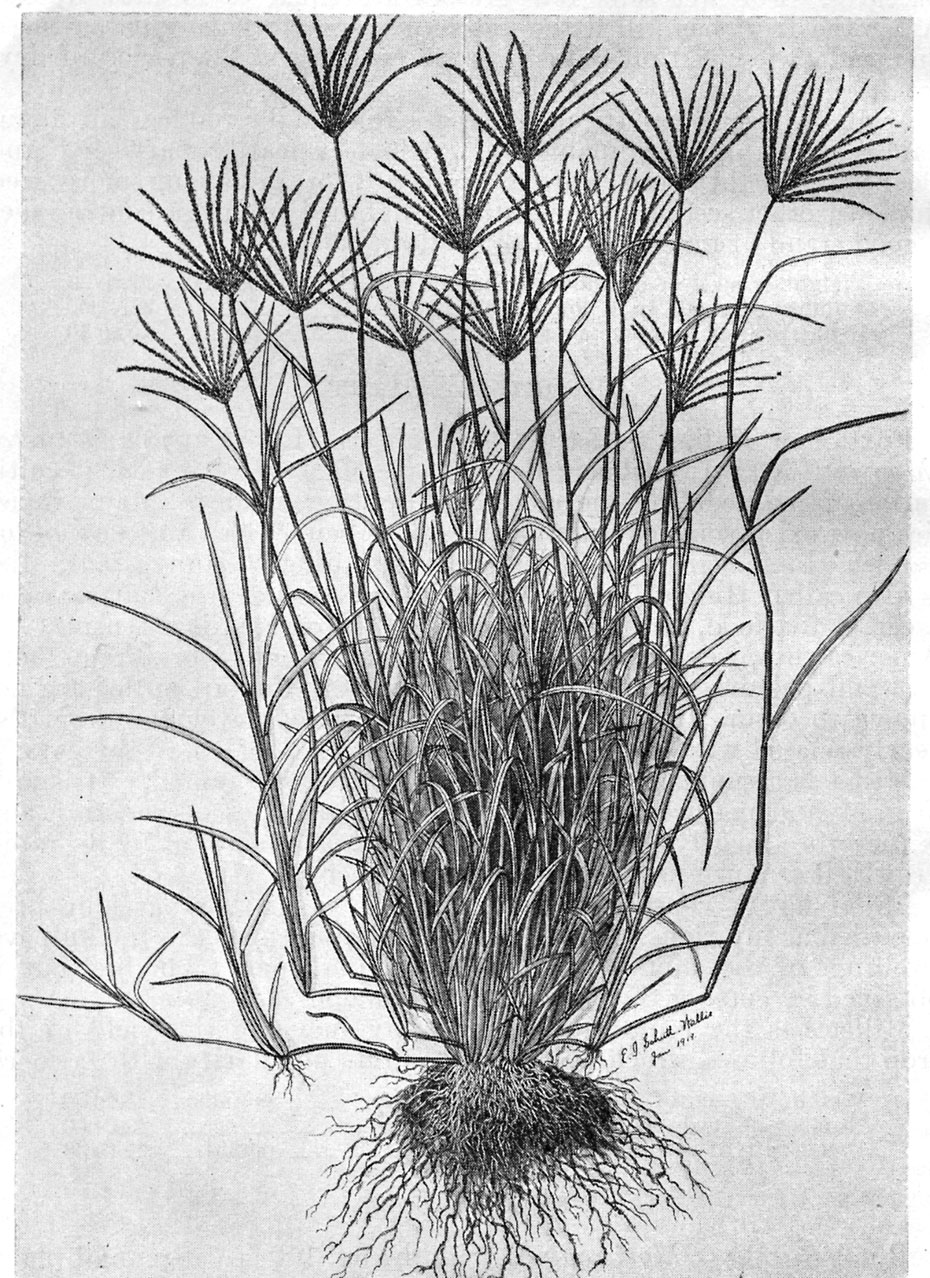

NAPIER GRASS

Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schumacher; Fig. 17) or Napier fodder (also called elephant grass) is a native of that part of Africa lying between the latitude of 10 degrees north and 20 degrees south. A more slender variety is called Merker grass. Napier grass is a perennial, having much the same habit as sugarcane. It grows in clumps, which consist of 20 to 200 stalks about an inch in diameter and 8 to 12 feet tall when in bloom. The leaves are one-half to 1 inch broad and 2 to 3 feet long. The flowers are in a long, narrow, erect, golden spike about 5 inches long. Napier grass is adapted to about the same area as Japanese sugarcane, namely, from Wilmington, N.C., west to Shreveport, La., and southward, and in southern California, but can be grown on the Atlantic coast as far north as Goldsboro, N.C., if the crown is given slight protection during the winter months.

Napier grass was first cultivated in Rhodesia in 1909, and from there it has been introduced into most warm countries. It was first obtained by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1913 and is proving to be very valuable, in Florida and California particularly. When mature, Napier grass is rather woody, but silage prepared from such plants is eaten clean by dairy cows. It is doubtless better, however, to cut two crops in a season for silage and thus avoid the woodiness. As a soiling crop for dairy cows Napier grass is most excellent and can be cut every three or four weeks in the growing season. The grass is eaten eagerly by all kinds of farm animals.

The grass is easily propagated by joints of the cane, which should be pushed into the ground so that the upper end is flush with the surface. It may also be grown from the seeds and the seedlings later transplanted.

SHEEP FESCUE

Sheep fescue (Festuca ovina L.; Fig. 18) is native in the Northern Hemisphere of the Old World, and apparently so in the New World, particularly about the Great Lakes and along the Rocky Mountains. It is a bunch grass, forming dense tufts 3 to 6 inches in diameter, with numerous stiff, rather sharp, nearly erect, bluish gray leaves, 2 to 4 inches long. The flower stalks are very slender and 6 to 18 inches high. This grass is adapted to about the same general climatic conditions as bluegrass and can be grown as far northward as any agriculture is possible. It succeeds better than most grasses in poor sandy or gravelly land and therefore is a valuable element of pastures on such soils. While the grass is decidedly tough, it is nutritious and eagerly eaten by sheep and to a less degree by cattle.

Sheep fescue is an excellent grass to grow on poor sandy soil, especially in mixtures, as it helps to make a durable grass sward. Alone it is too bunchy to be desirable.

The commercial seed of sheep fescue comes from Europe. It is easily gathered and is low in price.

Weight of seed of sheep fescue per bushel – 10 to 15 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 680,000

Usual rate of seedling per acre – 25 to 30 pounds

RED FESCUE

Red fescue (Festuca rubra L.; Fig. 19) is very similar to sheep fescue, but the leaves are bright green and the plant does not grow in tufts but creeps by underground stems, so that one plant may eventually cover a circle 2 to 4 feet in diameter. Red fescue occurs throughout the Northern Hemisphere in cold and temperate regions and has many varieties. Only two of these varieties are used in agriculture, namely, genuine red fescue (F. rubra genuina), the seed of which comes from Europe, and Chewings Fescue abundant in New Zealand, whence the seed supplies come.

Red fescue is used mainly as a lawn plant, but it is by no means valueless for pasture. On sandy or gravelly soil it makes exquisite lawns. It will withstand more shade than most grasses and is therefore valuable for shady lawns. On account of the fine quality of turf which it produces, it is much used on golf courses, particularly if the soil is sandy.

Weight of seed of red fescue per bushel – 10 to 15 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 500,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 30 pounds

PARA GRASS

Para grass (Panicum barbinode Trinius; Fig. 20) is a perennial, probably native of South America. It is readily distinguished by being covered with short hairs, which are longer and bristly at the nodes, and by its long creeping stems, often 30 feet long and as large as a lead pencil. Para grass is now commonly cultivated in most tropical countries. It is usually fed green and is often sold in bundles in the market. It is grown somewhat commonly in Florida, to a rapidly increasing extent in southern Texas, and here and there throughout the Gulf coast region. It makes its best growth on damp soils, though it has been fairly successful on Texas ranches on heavy soils without irrigation where irrigation is needed for most other crops. It is not injured by prolonged overflows and makes vigorous growth where the land has been under water for several weeks. It is especially valuable for planting on the margins of ponds and on soils too wet and seepy for the cultivation of other crops. It is used for both hay and pasture. Para grass will not withstand a lower temperature than about 18 degrees F. It is therefore adapted only to the extreme southern portion of the country, and perhaps to southern California. It has succeeded as far north as Charleston, S.C.

Para grass is usually propagated by planting pieces of the running stems. Such pieces 6 to 12 inches long and having three or four joints grow rapidly when simply pushed into freshly plowed ground, so propagation is neither difficult nor expensive. The first growth from the cuttings is in long prostrate runners nearly as thick as a lead pencil, but as soon as the ground is fairly well covered the branches become nearly erect, soon reaching a height of 3 or 4 feet; so the closer the cuttings are planted the sooner a crop for mowing will be produced. Cuttings may be planted at any time from early spring until as late as September, though late plantings will make little growth until the following season.

If wanted for hay, Para grass should be cut when it reaches a height of 3 to 4 feet. From three to five cuttings may be made in a season, and as 1 to 3 tons of hay per acre are obtained at each cutting the total yield is heavy. The hay is rather coarse, but is of excellent quality if cut as soon as it has made sufficient growth and before the stems become hard and woody. When the grass is allowed to stand too long before cutting the stems become woody and unpalatable.

Para grass may be grown from the seed, but seed has never been handled in commercial quantities, as vegetative propagation is so easy.

JAPANESE MILLET

Japanese millet (Echinochloa crusgalli edulis Hitchcock; E. crusgalli frumentacea (Roxburgh) W.F. Wight; Fig 21) was originally described from India. In early times it was grown extensively in Japan, hence the name Japanese millet. It is also called barnyard millet, being now regarded by high authorities as merely a cultivated variety of barnyard grass (E. crusgalli (L.)Beauvois). It is easily distinguished from foxtail millet by the different shape of the head and the absence of bristles.

Japanese millet will grow better in cool regions than will foxtail millet and so in the Untied States is most important in New England and the northern tier of States, but it will thrive in practically every part of the country. It is a taller and coarser plant than any of the foxtail millets and can be utilized as green feed, silage, or hay.

Weight of seed of Japanese millet per bushel – 32 to 35 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 155,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 30 pounds

ITALIAN RYEGRASS

Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lamarck; L. italicum R. Brown; Fig. 22) is readily distinguished from perennial ryegrass by the awn on each floret and by the young leaves being inrolled at first. The grass is not truly an annual, but under farm conditions few of the plants live more than one year. Each plant under favorable conditions makes a round bunch with 20 or more flowering shoots 1 ½ to 3 feet high. Many varieties have been distinguished, based on different criteria. Argentine ryegrass is an annual the seed of which is produced in Argentina. Westerworld ryegrass is a selection that lives two years; Pacey’s ryegrass in modern trade is merely the small or short seeds that are screened out from the larger ones.

Italian ryegrass is an important hay plant in Europe, where under proper manuring and irrigation it produces four to eight cuttings in a season, with recorded yields of 12 to 20 tons per acre. In the United States no such extraordinary yields have been secured, the normal record being a single cutting of 1 to 2 tons per acre. It is more valuable as a hay plant on the Pacific coast than elsewhere in the United States. Besides its use as an annual hay crop, Italian ryegrass is much used in temporary pastures, particularly in winter in the South, and in lawn mixtures. It produces a turf very quickly, and in the South it is a common practice to sow seed on Bermuda grass lawns every fall so as to have a bright-green winter sward.

Italian ryegrass can be sown in the fall in the southern half of the United States and on the Pacific coast, but in the Northern States spring sowing is to be preferred.

Seed is imported mainly from Europe. Some seed is produced at present in the Pacific Northwest, but generally contains considerable perennial ryegrass.

Weight of seed of Italian ryegrass per bushel – 24 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 275,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 35 pounds

PERENNIAL RYEGRASS

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.; Fig. 23) is also known as English or Australian ryegrass sometimes as darnel and Randall grass, but the last two names properly belong to other grasses.

It is a native of Europe and was the first of fall perennial grasses to be grown in pure culture for forage in England in the seventeenth century.

Perennial ryegrass is a tufted, short-lived perennial, which grows usually to a height of 1 ½ to 2 feet. It should not be confused with the wild rye because of the similarity of name. There are numerous long, narrow leaves near the base of the plant, but the seed stems are nearly naked. The under surface of the leaves is bright and glossy, which gives an attractive appearance to the grass, most noticeable early in the spring. It can be distinguished from Italian ryegrass by the flowers being awnless and the leaves folded in the bud, not inrolled. It has been a popular cultivated grass in England for at least three centuries and was early introduced in North America. In Europe it and Italian ryegrass are more important than any others.

In North America perennial ryegrass takes a very subordinate position when compared to timothy as a hay plant. The chief use which has been made of this grass is as an ingredient in permanent pasture mixtures and for lawn purposes. It can be used for an annual hay crop if desired, especially in the South and on the Pacific coast.

The seed of perennial ryegrass is generally imported into this country, the price being too low to encourage American farmers to compete in producing it. The germination of the seed is usually good, and the seedlings are especially vigorous. No one of the common grasses excels it in this respect.

The seed bed for perennial ryegrass should be prepared as for other grasses. A fine mellow surface on a compact subsoil gives the best results. It should be seeded early in the spring in the North or in late summer or early fall in the South. It does especially well when seeded in the autumn. Its ability to grow rapidly allows the plants to become well established before hard freezing occurs.

Weight of seed of perennial ryegrass per bushel – 24 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 330,000

Rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 35 pounds

COLONIAL BENT

Colonial bent (Agrostis tenuis Sibthorp; A. vulgaris Withering; Fig. 24) is the most common and abundant grass on well-drained soils in New England and New York and is not uncommon south to Virginia and Missouri and west to the Pacific. While it has every appearance of being native, a critical survey of all the evidence leaves no room to doubt that it was in reality introduced from the Old World. It has received many common names, including small redtop, finetop, and Burden grass.

Colonial bent is distinguished from redtop by its smaller size, narrow leaves, short ligule, and its peculiar open panicle, which does not become closer when mature. It grows 6 to 24 inches in height. It is a beautiful grass to make fine turf, and indeed its seed makes up a large proportion of the highly esteemed South German mixed bent seed. The seed of Colonial bent was formerly gathered in considerable quantities in New England, but through fraudulent adulteration with the cheaper seed of redtop largely lost its reputation. Recently the industry has been revived, and guaranteed seed is produced in New England and the Pacific Northwest and is imported from New Zealand and Canada.

The natural Colonial bent makes up much of the pastures of New England and New York, and it is not infrequently cut for hay, but the yield of hay is small. Unlike some other grasses, it thrives well on acid soils, and its turf is injured rather than improved by the use of lime.

Weight of seed of Colonial bent per bushel – 14 to 25 pounds

Number of seed in 1 pound – 7,700,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – 25 to 40 pounds

DALLIS GRASS

Dallis grass (Paspalum dilatatum Poiret; Fig. 25) is known also under the names of large water grass, golden crown grass, and hairy-flowered paspalum. It is a smooth perennial, with a deep, strong root system and grows in clumps or bunches 2 to 4 feet high. The leaves are numerous near the ground but few on the stems. The stems are slender and usually drooping with the weight of the flower clusters.

Dallis grass is a native of South America and was probably first introduced around New Orleans. It is recorded by specimens from Arkansas in 1879, Texas in 1880, and Louisiana in 1883. It now occurs abundantly from North Carolina to Florida and west to Arkansas and Texas. Farther north it is too tender.

In the Southern States, where it spreads naturally, some farmers have permanent meadows or pastures consisting largely or partly of Dallis grass. Owing to its tendency to lodge, this grass is better suited for pasture than for hay. It is one of the best winter pasture grasses for heavy, moist, black soils. It remains green all winter unless injured by severe frosts, and persistent grazing will not injure it. An immense number of leaves are produced, which are renewed more quickly after grazing than those of Bermuda grass, and under favorable conditions a Dallis grass pasture will last indefinitely. Permanent pastures of carpet grass or Bermuda grass are made more valuable by including this grass.

In seeding Dallis grass great care must be used to have the ground in the very best possible condition. The seed is very light; hence it is best to sow broadcast 5 to 10 pounds of handpicked seed per acre. Sow on ground which has been thoroughly harrowed and then roll or plank the seeds in. In the Southern States it is usually best to sow in October or November.

Under irrigation Dallis grass has proved to be an excellent forage crop in the San Joaquin Valley, Calif. Judging from the favorable experience in Australia, it ought to be valuable as a dry-land grass in many parts of the Southwest, where it should be fully tested.

Dallis grass produces seeds rather freely, but owing to the fact that they ripen from the tip downward and shatter off as soon as ripe, good viable seeds can be gathered only by hand. Seed is high-priced and usually of low germination. The best handpicked Australian seed rarely germinates more than 50 percent. In the Southern States the flowers are commonly affected with a black fungus which seems to injure the seed. At any rate, southern seed is very poor, often germinating only 5 to 10 percent. The fungus on the seed head causes a disease in cattle that feed upon it too freely, but this occurs only when the pastures are mainly of Dallis grass.

Weight of seed of Dallis grass per bushel – pounds – 15

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 340,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre – pounds – 5 to 10

SUDAN GRASS

Sudan grass (Sorghum sudanense (Piper) Stapf; Fig. 26) is an annual belonging to the sorghum family. It was imported from Khartum, Sudan, in 1909. In leaf, stem, and seed characters Sudan grass resembles Johnson grass very closely, but it lacks the underground stems or rootstocks which make Johnson grass difficult to eradicate.

When planted in rows and cultivated on fairly rich soil Sudan grass grows to a height of 7 to 9 feet, with stems one-fourth of an inch in diameter. Broadcast it rarely exceeds 3 to 5 feet in height, and the stems are much finer, one-eighth of an inch of less in diameter. The seed head is loose and open, like that of Johnson grass. The hulls, or glumes, are awned when in flower and often purplish in color, but the color usually fades to a pale yellow when ripe, and most of the awns are broken from the seed in threshing. Sudan grass is not particular about the soil, but it does best in a fairly rich clay loam. In sandy or poor soils the growth is rather weak and the yields low. It will stand slight frost, but continued cool weather interferes with its normal development, and this fact prevents its success in high altitudes. It is fully as drought resistant as the ordinary cultivated sorghums, and when grown in rows and given similar cultivation it can be relied upon to produce a crop of hay with very little rainfall. It has a short growing season, maturing for hay in about 75 to 80 days and for seed in 100 to 106 days from seeding time if the weather is warm.

Sudan grass should not be planted until the soil has become warm in the spring. It can be sown as a catch crop at any time during the summer as much as 70 to 80 days before the date of the first expected frost. Sudan grass can be sown in rows 18 to 42 inches apart and cultivated like corn, or it can be drilled in with a grain drill or sown broadcast by hand. Sudan grass makes very nutritious and palatable hay, which is greatly relished by both cattle and horses and has no worse fault than its slight laxativeness. Yields of 2 to 4 tons per acre of cured hay are common, and under irrigation they run as high as 8 to 10 tons. Sudan grass has attained wide popularity as a summer pasture crop and has exceptional merit for supplemental pasture during the customary drought period of late July and August. It is relished by all classes of livestock and on average soils will carry two mature cows per acre for two to three months.

A very limited number of cases of prussic-acid poisoning have been reported when grazing Sudan grass with cattle after it has been severely injured by drought or other unfavorable climatic factors, and the grass should be pastured with care under such conditions. Hogs can be pastured on the grass in safety, and horses and sheep are less susceptible to the poison than cattle.

Weight of seed of Sudan grass per bushel – 32 pounds

Number of seeds in 1 pound – 50,000

Usual rate of seeding per acre: Broadcast or close drills – 12 to 25 pounds

Rows 36 to 44 inches apart – 4 to 6 pounds

Rows 12 to 18 inches apart – 6 to 8 pounds