I was sorry to see 2022 come and go with so little mention of the bicentennial that fell that year. I refer not to the death of Percy Bysshe Shelley, the massacre of Greek patriots on Chios, nor to Brazil’s independence from Portugal, all of which occurred in 1822. I refer, instead, to the birth of Sir Harry Paget Flashman VC, KCB, KCIE, the hero of Piper’s Fort, Balaclava, and Cawnpore. For those unfamiliar with Flashman’s life, I’ll provide a brief summary.

Flashman was born to Lady Alicia Paget and Henry Buckley Flashman MP. After he was expelled from Rugby School at the age of 17, he joined the 11th Hussars under James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan, and was sent to Afghanistan, where he became one of the few Britons to make it back from Kabul during the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838–42). He subsequently saw action in the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–46), the Crimean War (1853–56), the Indian Rebellion (1857), the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64), the American Civil War (1861–65), the Second Franco-Mexican War (1861–67), and the Anglo-Zulu War (1879).

He knew or met nearly all the eminent Victorians, including Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, Chinese Gordon, Lord Palmerston, the Duke of Wellington, Benjamin Disraeli, Oscar Wilde, and Queen Victoria herself. His romantic conquests were no less illustrious. Lola Montez, Queen Ranavalona of Madagascar, and Daisy Greville, Edward VII’s mistress, all, at one time or another, shared Flashman’s bed (or he theirs). He was the only man to survive both the charge of the Light Brigade and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and he was (probably) the only man to sleep with both Lillie Langtry, the actress, and Yehonala, the last empress of China.

If you think that all sounds too extraordinary to be true, you’re right. Flashman was, in fact, born in the brain of novelist Thomas Hughes, whose 1857 novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays launched the craze for boarding school stories that swept through Britain in the late 19th century. Flashman, “the school-house bully,” only plays a supporting part in Hughes’s novel, getting booted from the plot at the same time that he gets booted from Rugby. And there his life in literature might have ended had George MacDonald Fraser not decided, sometime in 1966, to fill in the rest of Flashman’s story, as written by the man himself. Fraser insisted that he was merely the editor of Flashman’s memoirs, found in a tea chest during a country-house auction, and he provided footnotes and appendices to prove it. This was not a new conceit. Daniel Defoe and Vladimir Nabokov had tried something similar before. Yet Fraser evoked the Victorian era so deftly that many reviewers of the first Flashman novel fell for the ruse, taking the character for a real man. One critic even declared that the pages were the greatest find since the discovery of James Boswell’s diaries.

It was a fitting mistake, for Flashman is a brilliant con artist, capable of pulling the wool over almost anyone’s eyes. The running joke of the novels, which Fraser eventually stretched into 12 volumes, is that Britain’s greatest hero is, by his own admission, a fraud (“a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward—and, oh yes, a toady”) who would do just about anything to save his own skin. His record of misdeeds would make Lord Byron gasp: adultery, bigamy, rape, murder, torture, wife-beating, slave-driving, gunrunning, attempted opium dealing, and, naturally, betraying queen and country. When he’s up, he brags. When he’s down, he begs. There’s nary a racial slur he doesn’t know and none he won’t use, so long as the person on the receiving end poses no immediate threat. His terms for women include bint, chit, houri, strumpet, wench, slut, and harlot. He is, in short, part Falstaff and part Forrest Gump, boozing, womanizing, and quivering his way through every major historical event of his era.

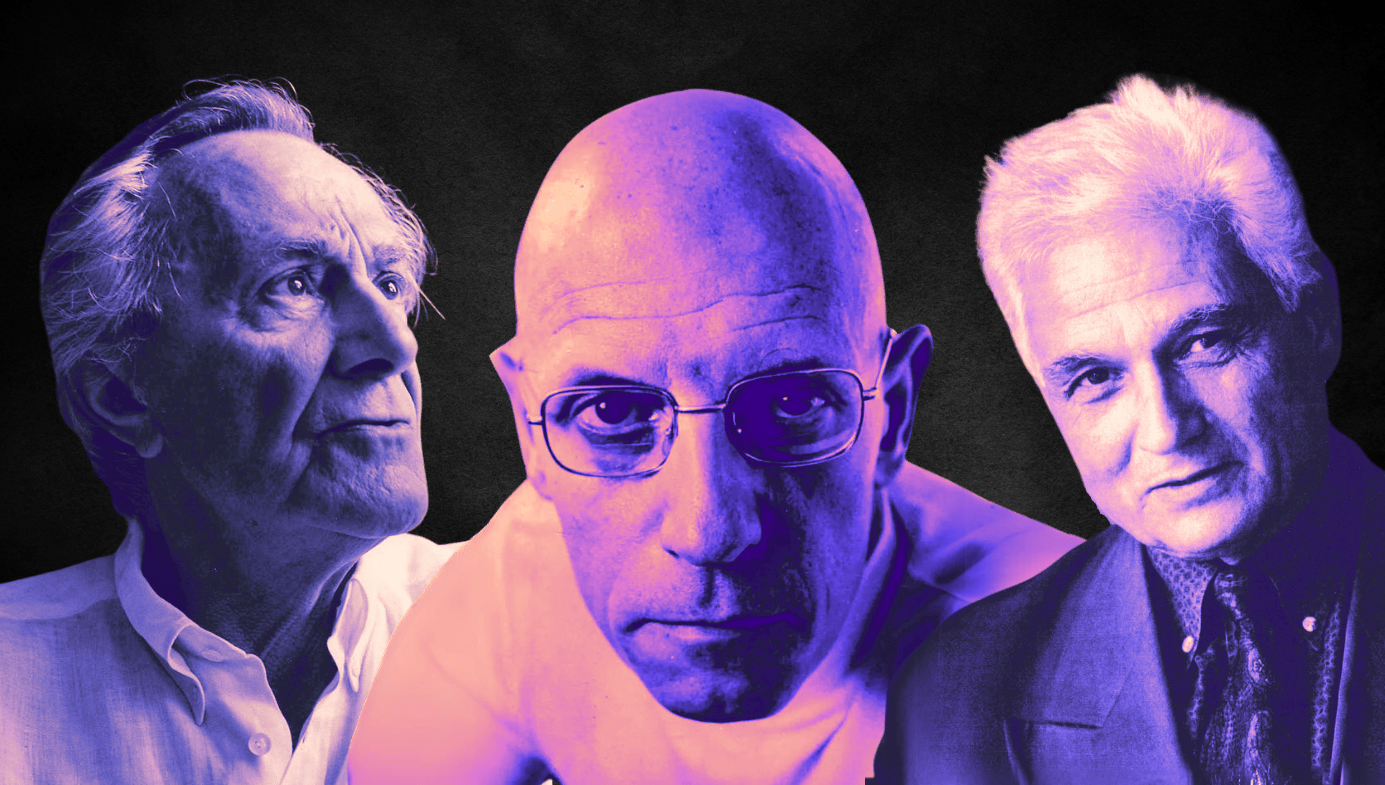

Who could love such a swine? Quite a few people, as it turns out. Flashman’s list of admirers is nearly as impressive as his list of lovers. Kingsley Amis, Christopher Hitchens, David Mamet, and Charlie Chaplin all confessed to being Flashy fans. P.G. Wodehouse rarely praised other novelists, but when Fraser’s name came up he gushed: “If ever there was a time when I felt that ‘watcher-of-the-skies-when-a-new-planet’ stuff, it was when I read the first Flashman [novel].” The character’s appeal derives, in part, from his candor. Though Flashman lies to everyone around him, he never lies to his readers. Indeed, he seems to take a perverse pleasure in recounting his most shameful deeds. “Hoaxing Bismarck into a prize-fight, convincing Jefferson Davis that I’d come to fix the lightning-rod, hitting Rudi Starnberg with a bottle of Cherry Heering, hurling Valentina out of the sledge into a snow-drift—all are fragrant leaves to press in the book of memory,” he reminisces in Flashman and the Dragon, before describing how, during the Taiping Rebellion, he duped one of his antagonists into being beheaded. And then, well, he’s just so funny. Here he is aboard the slave ship Balliol College, ministering to a dying comrade:

“Oh, I’m not sure, now,” says I. “Slaving ain’t that bad, you know.”

He groaned and closed his eyes. “There is no such sin on my conscience,” says he fretfully, which I didn’t understand. “It is my weak flesh that has betrayed me. I have so many sins—I have broken the seventh commandment . . .”

I couldn’t be sure about this; I had a suspicion it was the one about oxen and other livestock, which seemed unlikely, but with a man who’s half-delirious you can never tell.

Not everyone goes in for this sort of thing, of course. In a 2005 review, John Updike dismissed the Flashman books as “potboilers,” which is a little like knocking Raymond Chandler for writing detective fiction or criticizing John le Carré for writing spy novels—the accusation isn’t necessarily wrong, but it misses the point. The Flashman books are, in true potboiler fashion, full of sex and violence and last-minute escapes. Like James Bond, Flashman is constantly tumbling in and out of gun battles, torture chambers, and women’s boudoirs. Cowardice aside, he has 007’s brawn, good looks, and charm, along with his weakness for booze, cards, and casual sex. Both men repeatedly rescue the British Empire. Still, you’d never mistake a passage by Fraser for one by Ian Fleming. Here’s Fleming:

It was a room-shaped room with furniture-shaped furniture and dainty curtains. The bed was provided with an electric blanket. There was a vase containing three marigolds beside the bed and a book called Nature Cure Explained by Alan Moyle, M.N.B.A. Bond opened it and ascertained that the initials stood for “Member: British Naturopathic Association.” He turned off the central heating and opened the windows wide. The herb garden, row upon row of small nameless plants round a central sundial, smiled up at him.

And now have a taste of Fraser:

Then there were the Malay swordsmen who filled the sampans—big, flat-faced villains with muskets and the terrible, straight-bladed kampilan cleavers in their belts; the British tars in their canvas smocks and trousers and straw hats, their red faces grinning and sweating while they loaded Dido’s pinnace, singing “Whisky, Johnny” as they stamped and hauled; the silent Chinese cannoneers whose task it was to lash down the small guns in the bows of the sampans and long-boats, and stow the powder kegs and matches; the slim, olive-skinned Linga pirates who manned Paitingi’s spy-boats—astonishing craft these, for all the world like Varsity racing-shells, slim frail needles with thirty paddles that could skim across the water as fast as a man can run.

See the difference? Where one man sketches, the other paints in vibrant colors. Where one is allergic to specificity (“room-shaped room,” “furniture-shaped furniture,” “nameless plants”), the other grabs at it lustily: “sampans,” “kampilan cleavers,” “olive-skinned Linga pirates.”

Fraser was just as good at portraiture. Flashman was his crown jewel, but there are plenty of other gems in the series: the hero’s airheaded wife Elspeth; his cantankerous father-in-law, John Morrison; and John Charity Spring, the half-mad classicist who shanghaies Flashman aboard the Balliol College. Some of the most vivid people we meet are actual historical figures like Lord Cardigan, of Light Brigade fame, and John Brown, the abolitionist whose raid on Harpers Ferry helped precipitate the American Civil War. The most delightful of all is almost certainly the congressman from Illinois, whom Flashman first encounters at a Washington soirée in 1848: “I liked Abe Lincoln from the moment I first noticed him, leaning back in his chair with that hidden smile at the back of his eyes, gently cracking his knuckles.”

Fraser, however, refused to put a halo on anyone, even Honest Abe. His Lincoln may be cunning, quick-witted, and idealistic, but he’s still a creature of his time, declaring black people to be “the most confounded nuisance on this continent, not excepting the Democrats.” Those today who admonish the 16th president for being too cautious on the issue of slavery would undoubtedly enjoy this vignette, which appears in the third novel in the series, Flash for Freedom!. However, they probably wouldn’t be so pleased with what comes a little later, when Flashman gets a job on a Southern plantation. “Slave-driving is as pleasant an occupation as any, if you must work,” he explains. “You ride round the cotton rows on horse-back, seeing that the niggers don’t let up in filling their baskets, and laying on the leather when they slack.”

This passage, among others, would surely cause many modern sensitivity readers to recline on a fainting couch. And if the editors at Puffin Books—which recently bowdlerized passages from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, and The Witches—think that Roald Dahl is offensive, they should try reading Fraser’s 2002 memoir, The Light’s on at Signpost, which contains quotes like these:

I am in no doubt that given time and opportunity the ethnically cleansed will clean up their oppressors in turn, and so on ad infinitum, and if we had any sense we’d let them get on with it and mind our own business.

The restoration of corporal punishment is also long overdue. If there is a deterrent to match the rope, it is the cat, as many old lags will testify. The birch should also be reintroduced for juvenile offenders.

Women have no place in the Army, Navy, or RAF.

I cannot help feeling a dislike for the Japanese en masse.

I write as a convinced Imperialist—which means that I believe that the case for the British Empire as one of the best things that ever happened to an undeserving world is proved, open and shut.

Fraser, the Sunday Telegraph once quipped, wasn’t so much of the Old School as of the school they knocked down when the Old School was built. Born in England in 1925, he spent his childhood in Scotland, scrambling through the heather pretending he was fighting Afridis in the Khyber Pass. During the Second World War, he got a taste of the real thing. His unit, the Border Regiment, fought in the Burma campaign, fending off poisonous snakes, malarial mosquitoes, and jungle sores, in addition to Japanese bullets. After the war, Fraser returned to the UK and took up a career in journalism, but he wearied of the occupation when he realized he wasn’t going to rise above deputy editor at the Glasgow Herald. That’s when he began to think about writing a Victorian novel. Like many British lads, he’d read Tom Brown’s Schooldays. He didn’t care much for the hero or the other Holy Joes at the center of the story, but he found himself wondering what might have become of the villain, expelled for drinking too much beer and gin-punch.

The odd thing was that Fraser—stodgy, outmoded imperialist though he may have been—was, as a novelist, actually a keen critic of the British Empire. His books remind readers what a brutal beast John Bull was during the Victorian era, spilling blood from Gandamak to Rorke’s Drift. They never shy away from the dark side of empire-building, and anyone who still romanticizes British imperium ought to read the section in Flashman and the Dragon on the destruction of the Chinese Summer Palace. The Summer Palace was not just one building but an entire network of lakes, streams, gardens, and pavilions eight miles long, adorned with some of the finest art and architecture in the world. After a combined Anglo-French force captured Peking in 1860, James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin—the son of the Elgin who pillaged the Parthenon—ordered the palace to be burned to the ground. The utter malice of the act is beyond the pale, even for Flashman:

I guess, if drink and the devil were in me, I could ruin a Summer Palace in my own way, rampaging and whooping and hollering and breaking windows and heaving vases downstairs for the joy of hearing ’em smash, and stuffing my pockets with whatever I could lay hands on, like the fellows Wolseley and I watched at the Ewen. I’d certainly have to be drunk—but, yes, I know my nature; I’d do it, and revel in the doing, until I got fed up, or my eye lit on a woman.

But I couldn’t do it as it was done that day—methodically, carefully, almost by numbers, with a gang to each house, all ticked on the list, and smash goes the door under the axes. … Next to the wreck of a human body, nothing looks so foul as a pretty house in its setting, when the smoke eddies from the roof, and the glare shines in the windows.

By showing events like these through the eyes of a knave, Fraser was able to convey their repugnance without ever getting mawkish about it. (The same goes for the section aboard the Balliol College, in which Flashman describes the horror of the cargo hold, where the slaves are shackled, wallowing for weeks in their own vomit and excrement.) The fact that Flashman is such a scoundrel also makes him the perfect foil for the stiffs around him. Indeed, the biggest buffoons in the stories aren’t the Afghans, the Abyssinians, or the Chinese, all of whom are shown to be brave, intelligent, and dignified, but the British, who are so convinced of their own righteousness that they fail to see that their greatest hero is a louse. “Why, I’ve been a Danish prince, a Texas slave-dealer, an Arab sheik, a Cheyenne Dog Soldier, and a Yankee navy lieutenant in my time,” Flashy remarks, “and none of ’em was as hard to sustain as my lifetime’s impersonation of a British officer and gentleman.”

When Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy was being published, many critics observed that one of the things that makes her protagonist, Thomas Cromwell, so compelling is that he often seems like a modern man stuck in the 16th century. His respect for women puts the sexism of his era in sharper relief. His lack of religion makes the superstition of his peers all the more glaring. Something similar happens with Flashman. Unlike his fellows, Flashy doesn’t have romantic notions about glory or honor or the white man’s burden. When Lord Raglan admonishes him for failing to protect one of his comrades at the Battle of the Alma during the Crimean War, Flashman makes the salient point, so foreign to the Victorian mind: yes, he caused one man to killed, but Raglan, that very day, caused the death of thousands. Flashman is many things, but he’s neither a sententious fool (like Raglan) nor a blind conformist (like just about everyone else in the British army). In a society obsessed with bravery, he’s the only man who’s not afraid to admit that he’s a coward.

None of which is to say that the books are without fault. It’s easy to accept that Flashman is a poltroon when he’s cowering on a bed of straw in the first novel, letting his comrades fight the Battle of Jalalabad without him. But as the series goes on, and he’s repeatedly forced to throw himself into harm’s way, however reluctantly, the conceit begins to wear thin. A man who singlehandedly holds off half-a-dozen Chinese smugglers, while traveling upriver in the middle of the bloodiest civil war in human history, can’t honestly claim to have “a liver as yellow as yesterday’s custard.” The more stories you read, the more apparent the formula becomes. Each contains a long journey; a period of imprisonment; a gorgeous, horny vixen; an escape; an epic battle; and a moment in which our hero explains how his blundering changed the course of history. Since Flashman obviously lived long enough to write his memoirs, we never have to worry about him getting killed, and since the old soldier makes a cameo appearance in Mr. American, Fraser’s novel set in Edwardian England, we can be fairly certain that his dastardly deeds won’t be exposed in his own lifetime.

Yet the books are nearly impossible to put down. They can be read again and again without ever getting dull. Some, predictably, are better than others. Flashman and the Redskins goes off the rails about two-thirds of the way through, while Flashman and the Mountain of Light takes a maddening amount of time to kick into gear. By and large, though, they improved as the years went by. The footnotes became increasingly detailed, the use of slang became increasingly polished, and Flashman became an increasingly complex character. My mother used to say that Wilkins Micawber, the cheerful debtor in David Copperfield, felt more real to her than Henry Kissinger. There are, no doubt, plenty of people in Vietnam and East Timor who feel differently, but I know what she meant. Some literary characters are so well-drawn that you almost think they might walk through the door. Flashman is such a character. There are fan clubs online whose members pretend to believe—and, perhaps in some cases, genuinely do believe—that he was an actual person.

It’s no surprise that P.G. Wodehouse was a fan. Critics have often noted how much he and Fraser have in common: wit, a wealth of wonderful characters, and a talent for creating clever plots. The journalist Charles McGrath wrote that Flashman “sometimes sounds the way P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster would if Bertie had a libido.” You might also say that Fraser is Wodehouse with a cynical streak. The trouble with Wodehouseland is that it’s practically trouble-free. Wodehouse’s biographer Robert McCrum called it an “Edwardian Elysium”: “a world in which there is no greater threat than a punctured hot-water bottle, a flying flowerpot or Bertie’s Luminous Rabbit.” Fraser, on the other hand, gave us both the light and the dark, the comic hero and the tormented slaves, the bumbling British generals and the burning Summer Palace.

I said earlier that Fraser was a keen critic of the Empire, but that’s only half the story. In truth, he’s a keen critic of everyone, regardless of color, creed, or place of birth. He shows the British strapping Indian mutineers to the muzzles of the cannons at Gwalior, but he also shows Tewodros II, the emperor of Abyssinia, throwing 300 unarmed men, women, and children off the cliffs at Islamgee. When he describes the Indian practice of suttee—widow burning—he skewers both the colonizers and the colonized at once:

Like much beastliness in the world, suttee is inspired by religion, which means there’s no sense or reason to it—I’ve yet to meet an Indian who could tell me why it’s done, even, except that it’s a hallowed ritual, like posting a sentry to mind the Duke of Wellington’s horse fifty years after the old fellow had kicked the bucket. That, at least, was honest incompetence; if you want my opinion of widow-burning, the main reason for it is that it provides the sort of show the mob revels in, especially if the victims are young and personable, as they were in Jawaheer’s case. I wouldn’t have missed it myself, for it’s a fascinating horror—and I noticed, in my years in India, that the breast-beating Christians who denounced it were always first at the ringside.

No, my objection to it is on practical, not moral grounds; it’s a shameful waste of good womanhood, and all the worse because the stupid bitches are all for it. They’ve been brought up to believe it’s meet and right to be broiled along with the head of the house, you see—why, Alick Gardner told me of one funeral in Lahore where some poor little lass of nine was excused burning as being too young, and the silly chit threw herself off a high building. They burned her corpse anyway. That’s what comes of religion and keeping women in ignorance.

And there you have Flashman—castigating Hindus and Christians alike, simultaneously denouncing violence and reveling in it, condemning the cruelty of a patriarchal society while flaunting his own misogyny. The fact that so many of the events he describes honestly occurred only gives the humor more bite. “I go off the rails unless I stay all the time in a sort of artificial world of my own creation,” P.G. Wodehouse once confessed to a friend. “A real character in one of my books sticks out like a sore thumb.”

With Fraser, it’s just the opposite. You need to keep Wikipedia open as you read his novels just to keep track of who’s real and who’s not. It’s hard to believe that James Brooke, the White Rajah of Sarawak, was an actual person or that Lakshmibai, the queen of the Indian state of Jhansi, really put on a sowar’s uniform and charged the British at Gwalior, but it all checks out. “I am concerned with facts,” Flashman tells us in the first volume of his memoirs, “and since many of them are discreditable to me, you can rest assured they are true.”

It would be a shame if modern readers let those discreditable qualities stop them from enjoying Fraser’s novels. Some of the best heroes in literature, from Richard III to Raskolnikov, have been antiheroes. It was Fraser’s genius not only to create such a character but to blend him seamlessly into actual events. And that’s the great joy of the Flashman novels. You can hardly tell where history ends and fiction begins.