History

The Second War of Wales Independence from 1282-1283 ended with the defeat and occupation of large parts of the northern area by the English. The Welsh abbey and settlement at Aberconwy were conquered in spring 1283, and the nearby Deganwy castle defending the Conwy estuary was destroyed. Instead of rebuilding the old stronghold, king Edward I ordered to erect a new fortress and town; a symbol of English power, the administrative capital of the new county, populated with English colonists. The construction of the castle, designed by James of Saint George, the main architect and master of the masonry of the king, began in March 1283. The monks from Aberconwy Abbey were transferred to Maenan, about 13 kilometers upriver, and their former seat was transformed into the temporary quarters of the king and his entourage. From the area of England, a group of workers were taken, who completed the work to an unprecedentedly quick time until 1287. The cost of the castle and the town fortifications amounted to a huge then sum of 15 thousand pounds. The castle’s constable was, by a royal charter of 1284, also the mayor of the new town and supervised a castle garrison of 30 soldiers, including 15 crossbowmen, supported by a carpenter, chaplain, blacksmith, engineer and stonemason.

In 1294, the castle was besieged by Welsh insurgents of Madog ap Llywelyn. The rebels quickly captured the royal strongholds at Caernarfon, Castell y Bere and Harlech, as well as the castles of the king’s vassals at Denbigh, Hawarden and Ruthin. The scale of the revolt made Edward I cancel the planned campaign on the continent and instead lead the army to North Wales. However, he fell into the trap of Madog’s forces and had to flee to the Conwy castle, where he was besieged from December 1294 to February 1295. The strong defense of the castle and the ability to send supplies by the sea, meant that the Welsh were not able to get it, and the defenders received relief. The Madog’s revolt ended in the Battle of Maes Moydog in 1295. Castle Conwy however hosted Edward, Prince of Wales and later king of England, when he arrived in 1301 to receive homage from the Welsh leaders.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the castle was not well managed, the roofs were leaking, and the timber parts were rotting. The condition of the castle armory was also poor, a large part of the weapons was damaged or neglected. For example, out of 30 crossbows, only 10 were usable, and out of 21 bows none had bowstrings. This situation lasted until 1343, when Edward, the Black Prince, took control of the stronghold. Sir John Weston, his chamberlain, in the years 1346-1347 carried out repairs and building, among other things, a new vault for the great hall of the castle and probably in the royal chambers at the upper (inner) ward. However, after the death of the Black Prince, Conwy fell into neglect again, of which documents from the end of the fourteenth century mention.

In 1400 another Welsh uprising broke out under Owain Glyndŵr. In March 1401, the cousins of Glyndŵr, Gwilym and Rhys ap Tudor and their men captured the castle by trickery. Pretending to be carpenters and workers, they killed guards and called for help from hidden comrades. The English responded with the siege of Conwy, who defended for three months before the rebels negotiated a peaceful capitulation. The talks were held for quite a long time, as the Welsh had earlier plundered the town and some Englishmen refused to let them go on gentle conditions. For the remainder of the 15th century, the castle’s significance decreased, although during the Wars of the Roses were again provided and strengthened.

During the reign of Henry VIII in the 20s and 30s of the 16th century, small conservation works were carried out at the castle, the stronghold was then used as a prison, depot and as a potential residence for guests. At the time, however, not too much money was allocated to the castles of North Wales, because they lay far from the center of political power, and tensions between the native inhabitants of these lands and the English gradually decreased under the rule of the Tudors, a dynasty derived from Wales. In 1627, Conwy Castle ceased to be a royal building, as Edward, the first Conwy Baron, bought it for £ 100. It was probably a symbolic purchase, because the castle was then in a state near to ruin.

With the outbreak of the English Civil War, the castle was taken in 1642 by the royalist John Williams, the Archbishop of York and re-adopted for defense. Warfare evaded Conwy until 1646, when the forces of Parliament led by Thomas Mytton besieged and occupied the fortress. In 1655, the State Council appointed by the Parliament ordered that the castle should be demolished or deprived of military significance. In the 60s of the 17th century, the castle’s constable, Earl Edward Conway, decided to get rid of the iron and lead remainder in the castle and sell it. Demolition was carried out, despite opposition from the leading citizens of Conwy and turned the stronghold into ruin. Conservation works began in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the monument became the property of the town. In 1953, it was leased to the Ministry of Labor, which resulted in a wide program of repairs and research on the history of the castle.

Architecture

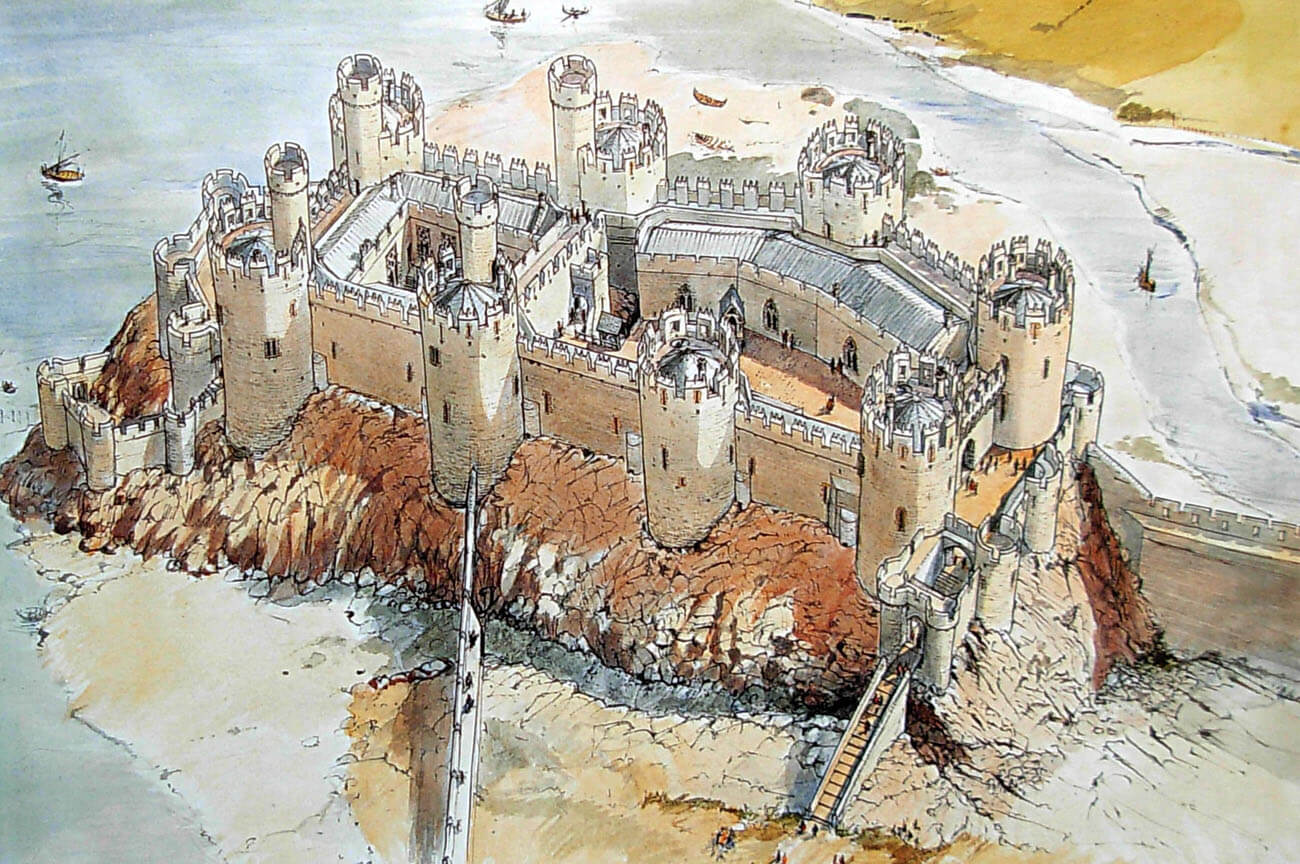

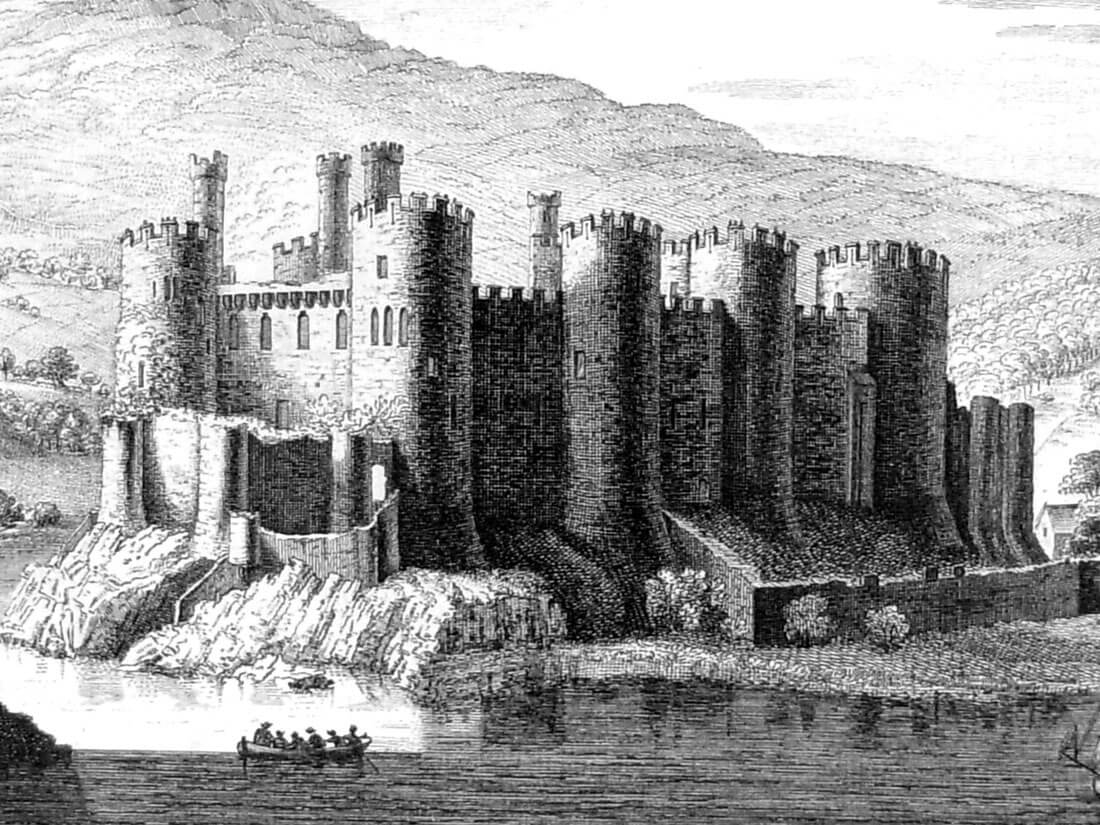

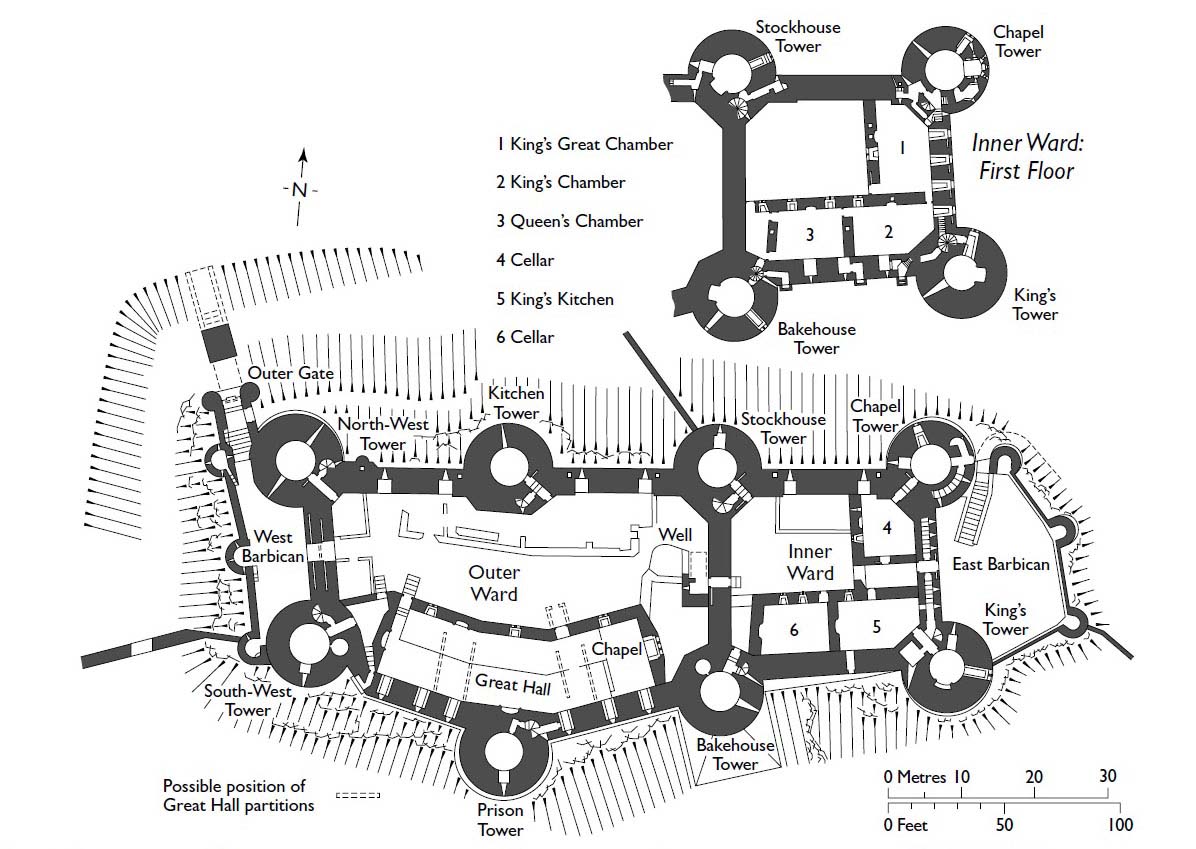

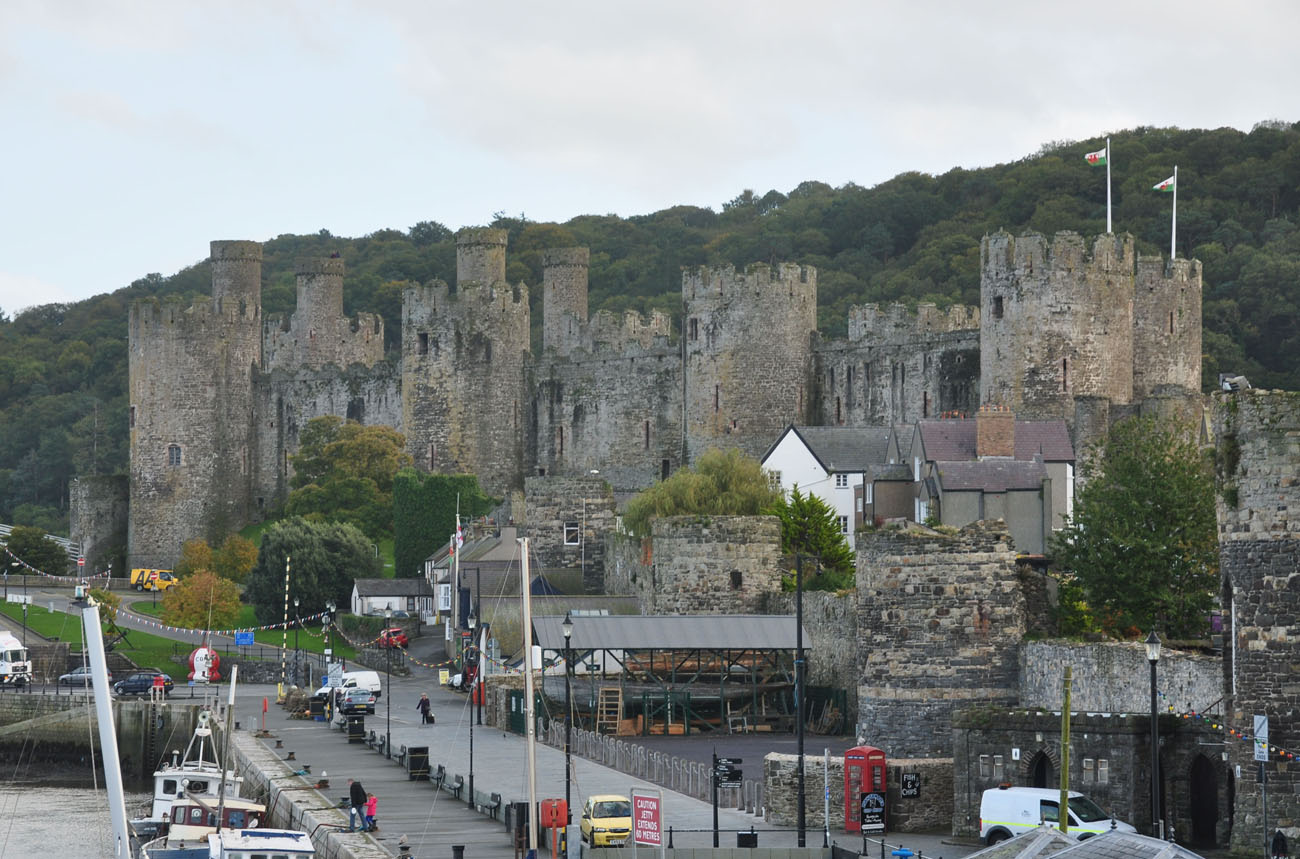

The castle was erected on a coastal, rocky ridge from which gray limestone and sandstone were probably taken for construction. For finishing elements and details such as, for example, door and window portals, more colorful sandstone was imported from the Creuddyn peninsula and the English area of Chester. In the Middle Ages, the walls of the castle were probably whitewashed, mainly to protect against the harmful effects of rainwater. From the most endangered north and west side, not protected by a water obstacle, the castle was preceded by a cut in the rock ditch. It was on this section that the castle was adjacent to the town with which fortifications it was connected. They were in contact with a wall of the barbican at the south-west tower and the northern Stockhouse Tower. From the south, the town and the castle were protected by the Gyffin River, while from the east the Conway River flowed widely.

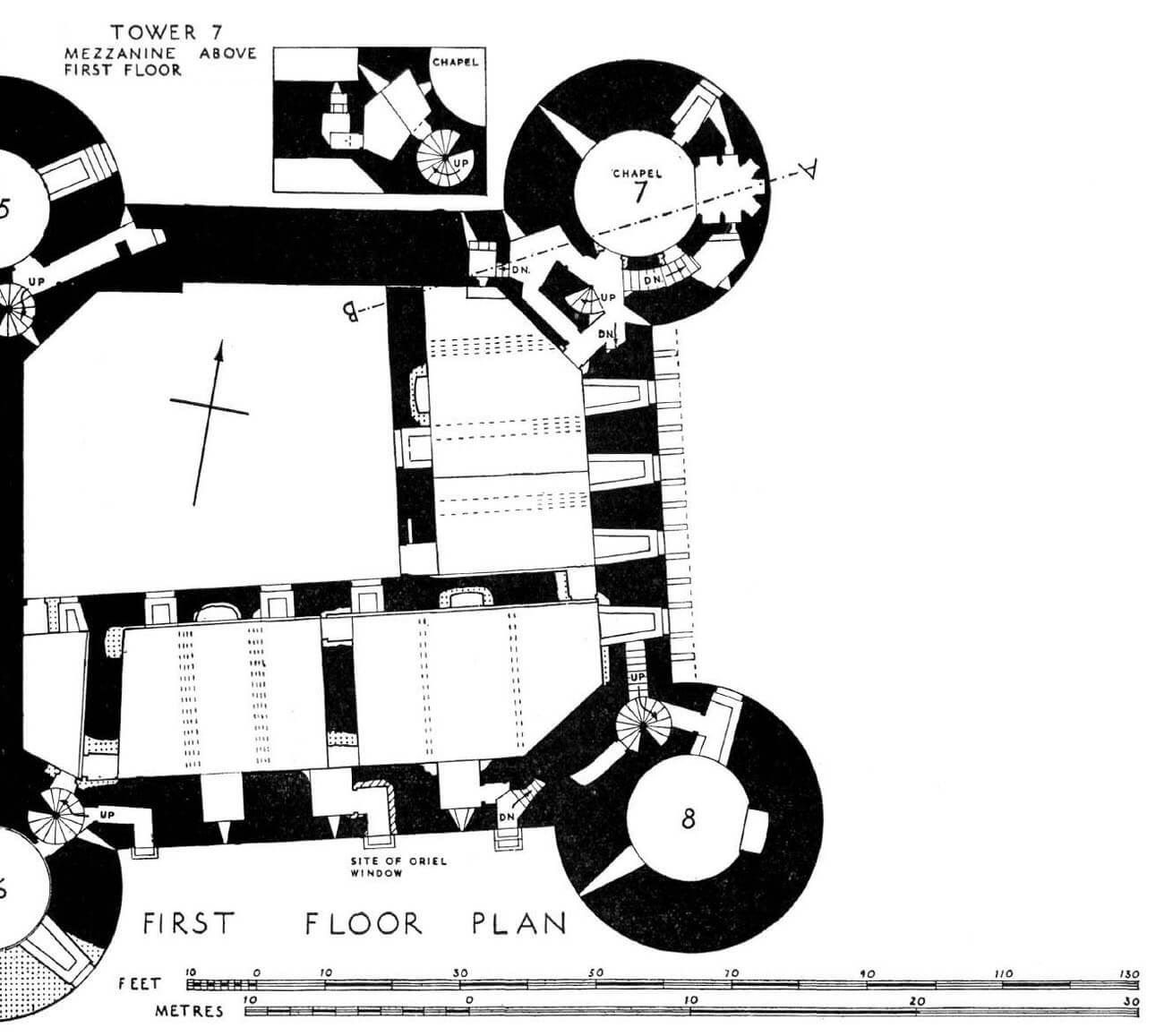

The stronghold consists of two parts: a smaller one on the east side with a shape similar to a square, closing the inner (upper) ward with a defensive wall and four corner towers, and a larger western one with a shape similar to a pentagon, with defensive walls and six towers surrounding the outer (lower) ward. Two of these towers also form the eastern part, so the castle has eight main, round towers in total (slightly widened at the base), arranged quite symmetrically four from the north and four from the south. The regularity of the castle was disturbed only in the southern part of the lower ward, where the builders used the coastal rocky outcrop of the area, wanting to lead the defensive circuit along its edges. The architecture of the castle, among other things, through the appearance of the windows and the type of battlement, referred to the constructions of Savoy from the end of the 13th century. This may have been due to the origin of the chief architect, James of Saint George, from that region, as well as perhaps other craftsmen working on finishing the building.

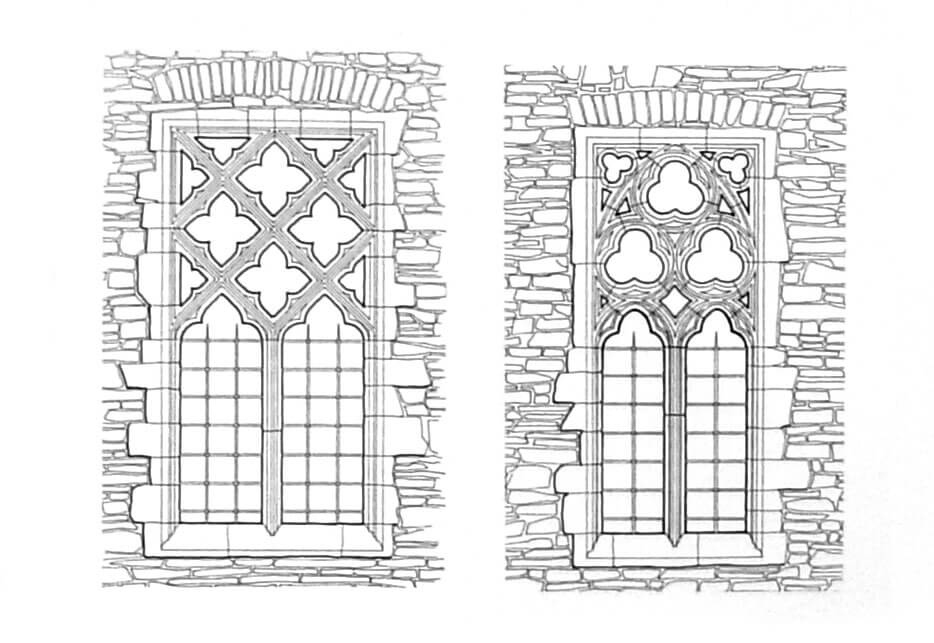

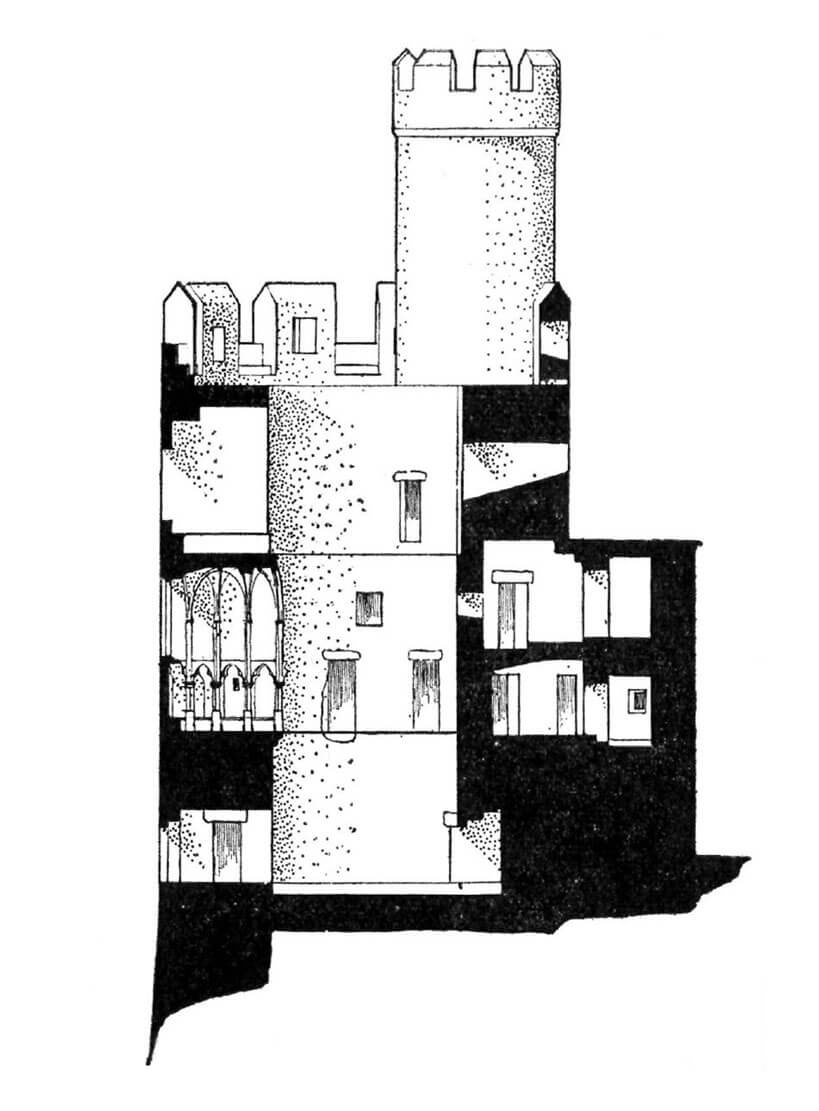

The main towers reached a height of 21 meters, had mostly two floors above the ground floor connected by spiral staircases and were strongly extended in front the face of the curtain walls, enabling flank fire. Similarly to the defensive walls of the castle, they were crowned with battlement and three stone small pillars on each merlon (detail probably moved to Wales by Savoy builders, found among others at the castle of San Giorgio in Italy). Unlike the wall, the tower’s merlons also had arrowslits, placed interchangeably on two different levels to be able to fire far and near foreground of the castle. Below them, square holes have been preserved to this day. There is no certainty as to what they originally served, they could be drainage holes for rainwater, supports for timber hoarding or openings for placing decorative shields. Four of the towers on the eastern side, that is all surrounding the upper ward, were additionally crowned with smaller cylindrical turrets. Probably they were raised in this way to protect the most important part of the castle and had better visibility to the river side. Additionally, banners could be placed in their upper parts, hung when king or Prince of Wales were in the castle. The walls of all the towers were pierced with narrow arrwoslits, but also larger rectangular windows, initially divided by vertical mullions and tracery. These windows provided better lighting in living quarters and were equipped with side stone seats from the inside. From the outside, they were secured with iron bars and closed with wooden shutters.

The defensive walls were short, straight curtains connecting the towers, set on a battered pedestal, with an average thickness of 3 to 3.3 meters and a height of about 9.1 meters above the level of the courtyards. In their crown there was a wall-walk, fully embedded on the offset, without the need to widen it with a wooden porch, providing the possibility of going around the entire perimeter, while the towers were bypassed on the inside on the stone porch suspended on corbels. Also, the transverse wall dividing both courtyards was topped with a wall-walk. On it there were also the only doors securing the entrance to it and the passage from the western to the eastern part of the castle. The curtains were topped, similarly to the towers, with a breastwork, 1.8-2.1 meters high, with battlement with triple pillars, but without arrowslits in the merlons and set on the cornice. The façades of the walls were pierced with latrine chutes. Those from the town side were placed low, in a slightly thickened wall, just above the level of the rocky ground. As potential weak points of defense, their outlets were secured with brick covers (one has been preserved at the north-eastern tower). On the southern side the latrines were corbelled out beyoned the wall-face. At the ground level, in the curtains there were arrowslits, embedded from the inside in segmental closed recesses, and from the outside secured with horizontal bars. There were no passages connecting the towers in the thickness of the curtains, except for the eastern curtain, where two flights of stairs led from the postern to the corner towers. It was possible to get to the crown of the walls only through these stairs and by the spiral staircases in all of the the towers. The doors from the towers to the curtains were secured with bars (except at the south-west and south-east).

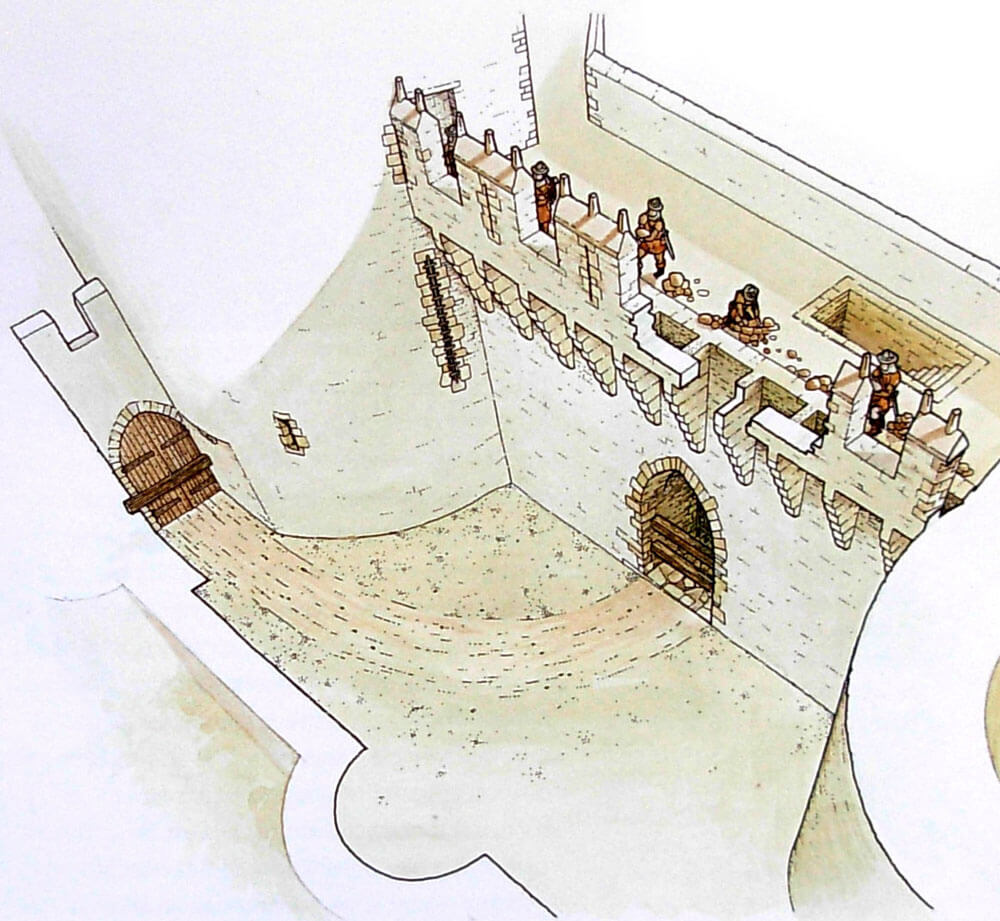

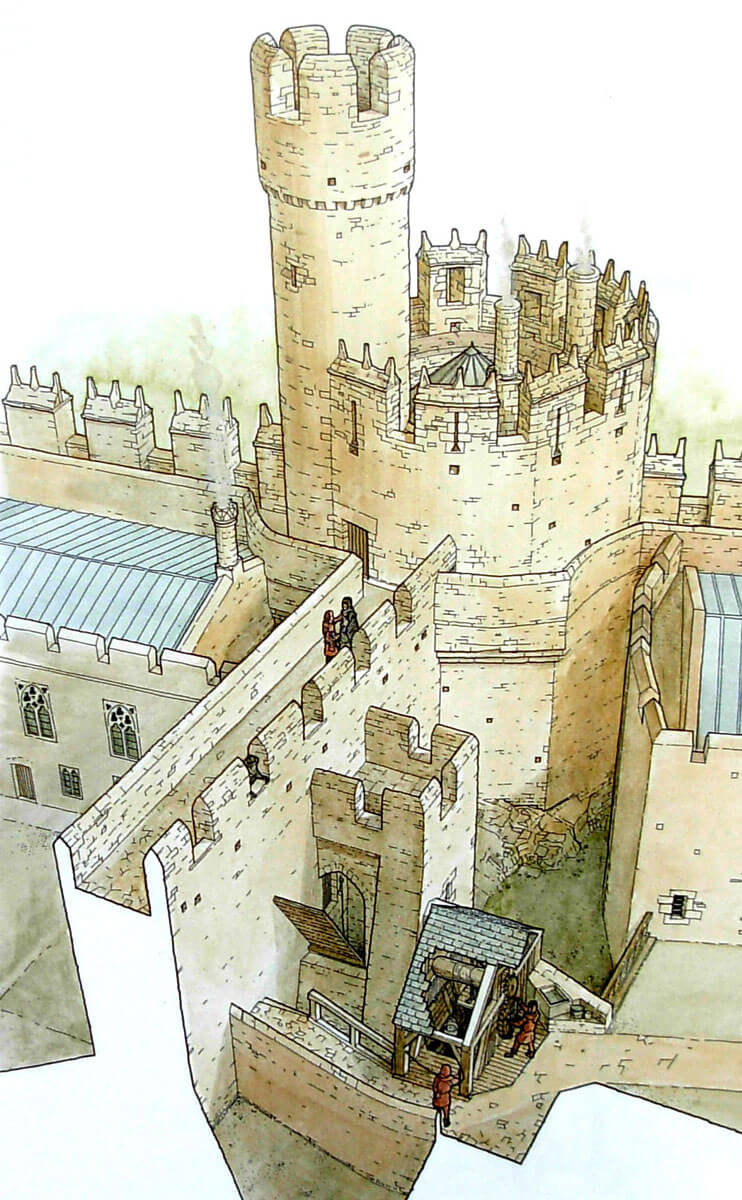

The main entrance to the castle led through the so-called western barbican reinforced with three semicircular turrets and the form of a foregate ended with another two turrets, this time cylindrical, flanking the foregate closed with a portcullis. Its mechanism could be located in a small room above the passage arcade, reached via stone stairs from both sides of the entrance. Originally, the foregate was entered via a stone ramp with stairs and then across the drawbridge. The southern end of the uncovered foregate was closed, however, with wooden doors located in a narrow passage at the north-west tower, leading to a slightly larger yard of the barbican. The west wall of the castle dominating the barbican had machicolation, one of the earliest in Wales and England. It was supported on multi-tiered stone corbels, between which downward pointing holes were created. Some of them were placed directly above the main entrance portal, leading to a short, but double-door, passage, blocked with very long transverse bars embedded in openings in the wall and secured with a portcullis. An additional protection was, of course, the two main towers: the north-west and south-west, strongly extended beyond the face of the walls and thus flanking the gate. On the courtyard side, the gate passage was originally extended by two small buildings, stone ones on the ground floor level, and above the half-timbered structure. They housed the guard chambers on the ground floor and the mechanism for raising the portcullis on the first floor.

The eastern part of the castle was also protected by the so-called barbican leading to the Water Gate and castle harbor. The area of that barbican, enclosed by a wall reinforced with three semi-circular towers (closed from the inside with wooden walls), was larger than the west one. Probably there were gardens in it, although because of the harbor, the eastern wall of the castle was also defended by machicolation. Below, another defensive wall was erected with two or three half-towers (opened from the inside) and a cylindrical tower extended towards the south, probably located practically on the water line.

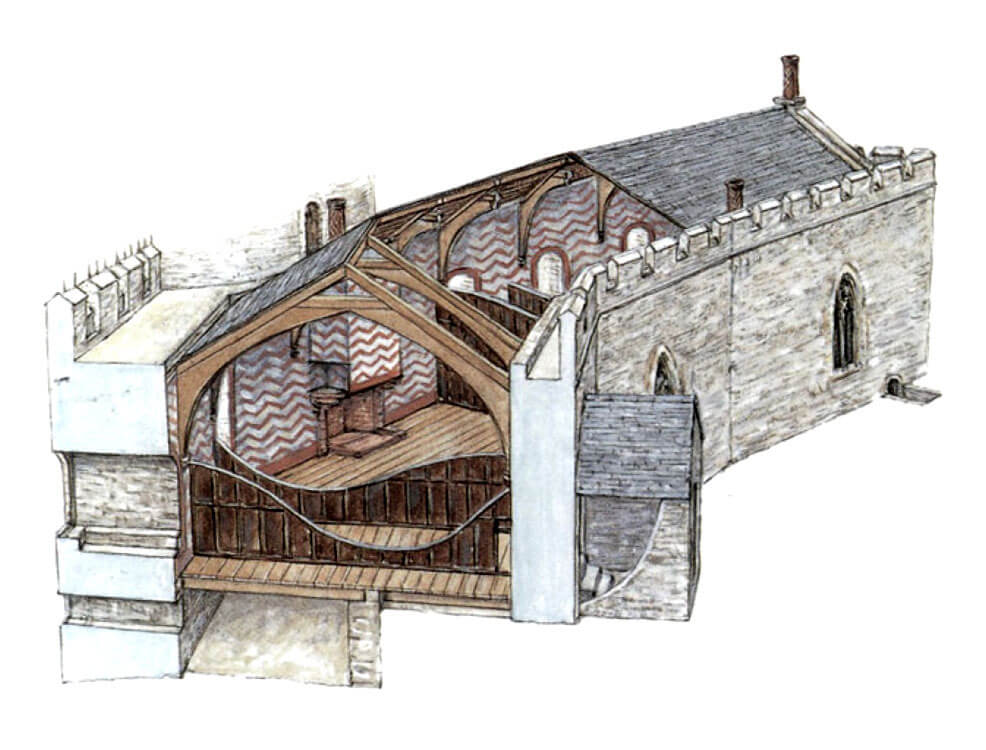

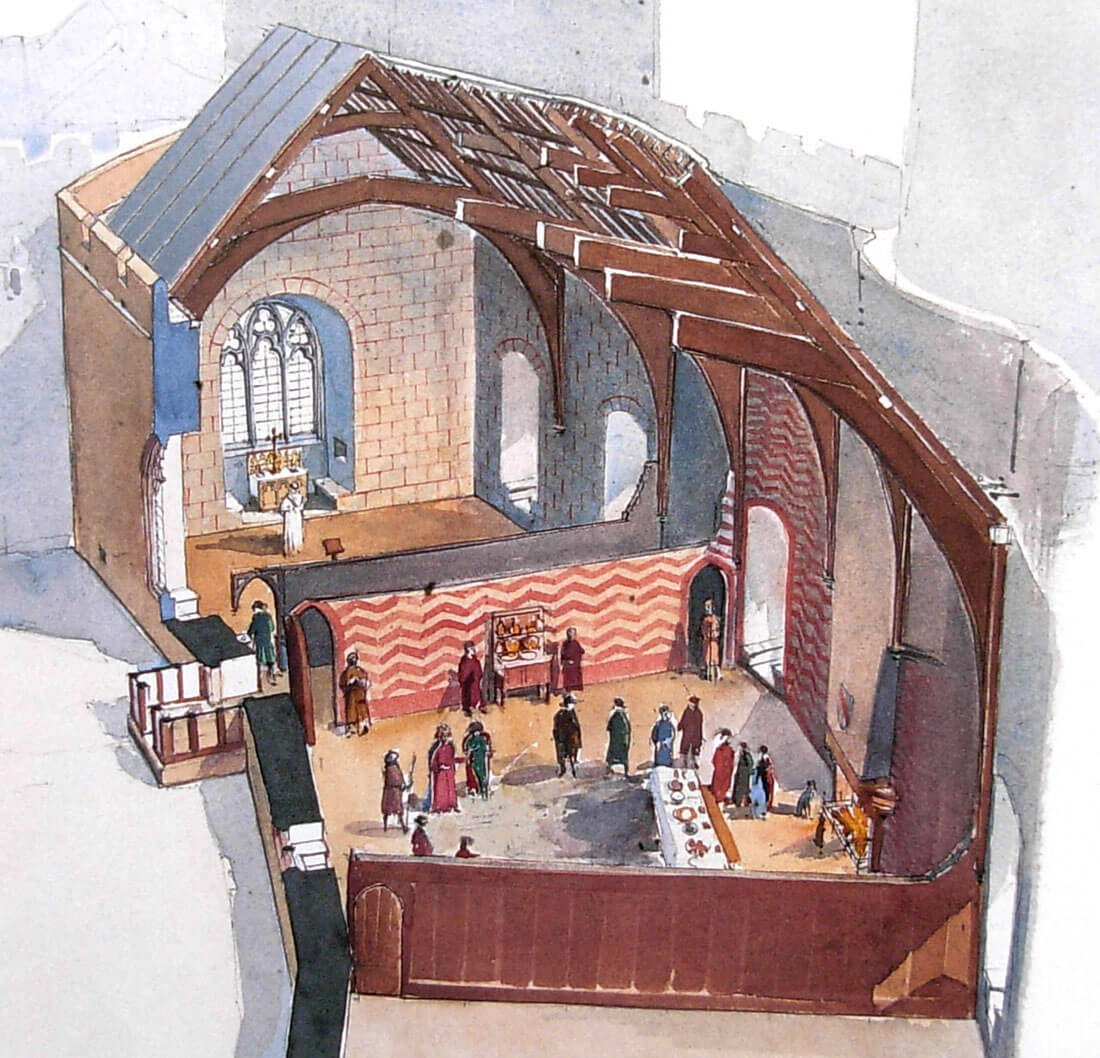

The lower (outer) ward (50 x 30 meters) was protected from the north by the Stockhouse, Kitchen and north-west towers, and from the south by Bakehouse, Prison and south-west towers. It mainly had administrative and economic rooms, including stables, a kitchen, a bakery and a brewery, so originally that there was not much free space in the courtyard. The curved building of the great hall and the chapel adjoined the southern defensive wall. From the side of the courtyard, it had large, ogival Gothic windows, six slightly smaller with rectangular frames and stonr seats illuminated the building from the south. In the Middle Ages at the ground floor level it was divided by wooden screens, with three fireplaces indicating that they could have been at least three rooms. The central part was occupied by a representative great hall, a place for feasts, ceremonies, hearings and meeting guests. In the chapel, the altar was in a niche on the east side, housing a large window with a sophisticated tracery. Below southern and eastern part of the great hall the rocky ground was cut to create a basement, accessible from the courtyard through the stairs in the west corner. The main entrance at ground level was preceded by a timber vestibule. Initially, the building of the great hall was topped with an open truss and a lead roof. In the years 1346-1347, these elements were replaced by eight stone arcades supporting the new roofing.

The names of the towers mostly reflect their original purpose: so there was a bakery with an oven, a pantry and a cellar dungeon intended for prison. The north-west tower was accessible from the courtyard only through the guard’s building at the gate. Its basement was unwarmed and illuminated only by narrow slit openings, which is why it was probably used as a warehouse or pantry. The two upper floors of the tower were already more comfortable: they had fireplaces and two-light large windows with side seats. In addition, from the spiral staircase by the passage between the first and second floor one could reach a small latrine placed in the wall thickness.

The south-west tower already had a direct entrance from the side of the narrow courtyard, from which a tight passage led to a common latrine in the thickness of the curtain wall. The tower’s ground floor served as a bakery which housed a bread oven by the eastern wall, originally there was also a basement. The upper storey was equipped with a large fireplace, a two-light south-facing window with side seats and a large wall-chamber measuring 5.2 x 2.4 meters, connected to the latrine in the southern curtain. The chamber was located behind the kitchen funnel, so it could be heated by it. The second floor was warmed by a fireplace and the lighting was mainly provided by a two-light eastern window. On its northern side, the passage led to the lobby and then to the crown of the defensive wall or to the staircase, while the second passage led down six steps to the latrine.

The Prison Tower was located on the south side of the great hall, half its length. The two highest floors of the tower were occupied by fairly comfortable chambers heated by fireplaces and illuminated with large windows with stone benches on the sides. In addition, there was a passage between them to the latrine suspended on the wall by the tower. From the level of the hall through the portal in the window niche, a corridor in the thickness of the curtain wall led through two doors and turn right to the room in the ground floor of the tower. It was different than in the ground floor rooms of other towers, because its entrance portal was placed 1.3 meters above the floor, i.e. it was practically inaccessible without using a ladder, and the door was closed from the outside with a wooden bar. This room was used to isolate smaller criminals (previously tried in the great hall), while the most important prisoners were thrown through a hole in the floor into a basement, 3.1 meters deep. Its cylindrical interior with smooth, vertical walls was illuminated only by a single, small opening located high above the floor. The thickness of the walls of the Prison Tower at the base reached 3.7 meters.

The Kitchen Tower defended the central part of the northern wall of the lower courtyard. It housed two floors above the ground floor, with both upper chambers warmed by fireplaces and connected to the ground floor via a spiral staircase. The lowest floor could serve as a pantry connected to the kitchen building next to it. The first floor from the east was illuminated by a two-light window with a four-sided jamb and side seats in the recess, and two loop holes: from the north and west. From the recess of the southern one the passage led to the latrine in the western curtain, also lit with a slit opening. Another latrine in the eastern curtain was reached from the passage connected with the staircase. The second floor was illuminated by a similar two-light window, and communication was provided by a passage to the wall-walk and to the staircase.

The inner ward was separated from the outer (lower) ward by a defensive wall between the Bakehouse and Stockhouse towers, next to which there was a gatehouse with a drawbridge and a portcullis, above a dry moat carved in rock. Because the upper ward housed royal apartments, this part of the castle had to be separated from the lower ward for defensive reasons. At the top, at the level of defensive walkways in the crown of the walls, gates were installed at the Bakehouse and Stockhouse towers (the rebates in the walls are still visible), and below the drawbridge fell parallel to the defensive wall and was settled on a kind of causeway led through a ditch. Defenders located on the gallery in the crown of the defensive wall and perhaps also on the gatehouse could watch over the whole area. Beside it at the lower ward was also a well 27.7 meters deep, fed from a spring dug in a ditch. According to records from the 16th century, it was topped with a gable roof and equipped with a turnstile for pulling out buckets.

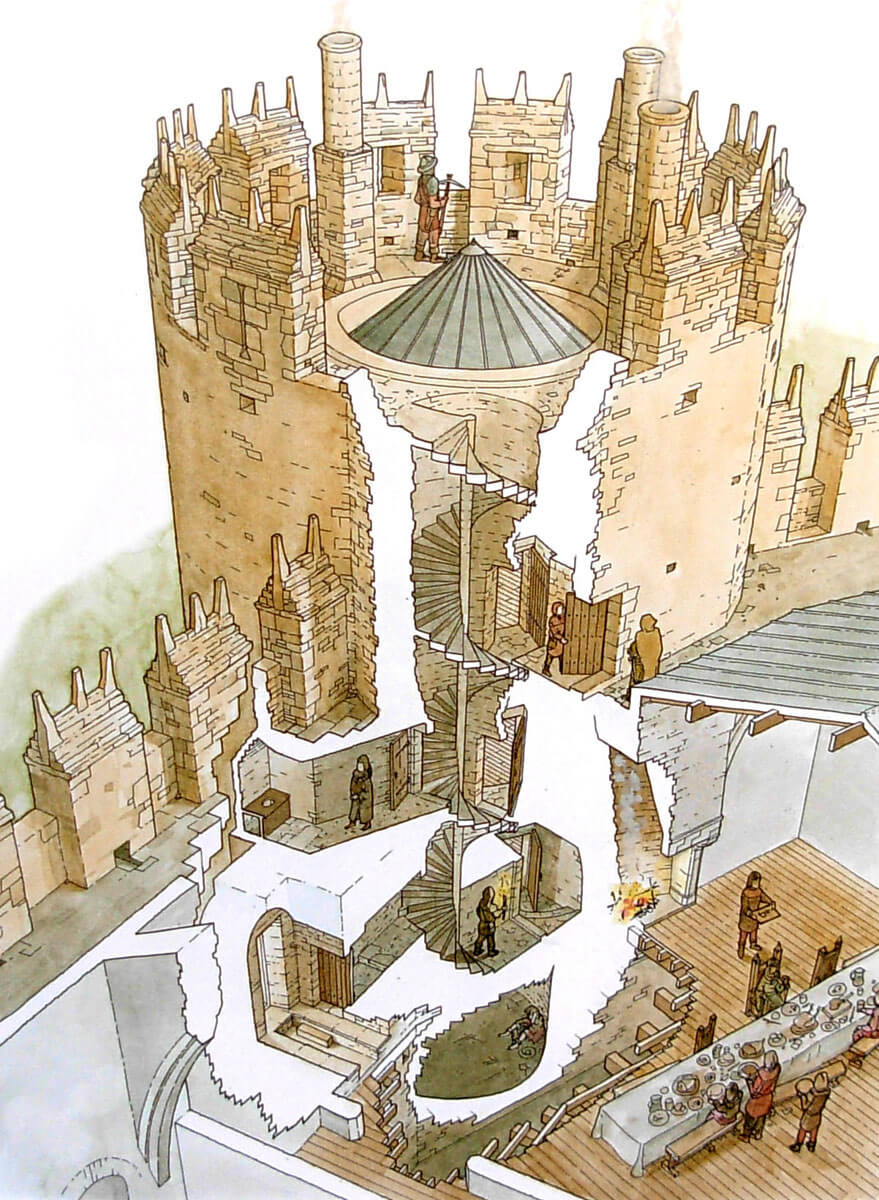

The upper ward (25 x 22 meters) had royal chambers and economic rooms for servants. They were placed in L-shaped building, attached to the defensive wall in the south and east, and thus separating a small courtyard from the north-west. In addition, in the northern part there was a small half-timbered building, referred to as the “granary” in the fourteenth century.

The first floor of residential buildings was accessible thanks to external timber stairs and a stone staircase located in the thickness of the eastern wall. The north flight of stone stairs led to the king’s great chamber and further to the chapel, thanks to which it was possible to get directly from the harbour to the chambers, without entering to the castle courtyard. The southern flight of stairs led to the staircase in the south-eastern tower. The external timber stairs were placed in two places, separate for the queen and separate for the king on the east side of the courtyard. The royal rooms occupied the entire first floor: in the south-west part it was the queen’s chamber, in the south-east the king’s chamber, and in the north-east the so-called the king’s great chamber.

The king’s great chamber was the largest room at the upper ward in which the ruler could privately receive guests and had a bit of privacy. A large fireplace was placed in its western wall and next to it the largest of the upper ward windows, decorated in the upper part with a tracery in the shape of the cross of St. Andrew. Smaller three windows also faced the east side, the castle gardens and the river. It were divided by mullions into two lights and a four-sided opening above, glazed or closed with shutters, and also protected by iron bars. The roof of the chamber was to be set on three pointed, chamfered arcades, but it is not certain whether it was completed according to the original plans and the wooden roof truss was not used.

The corner king’s chamber was a place where he could spend most of the day and sleep at night. Comfortable conditions were provided by a fireplace and a latrine accessible through a portal in the southern window niche. In addition, the chamber was connected to the queen’s chamber in the west, a large chamber in the north and two discreet passages from the King’s Tower through a low staircase and a narrow passage in the wall reaching the king’s chamber in the niches in the east and south. The southern one led from the ground floor kitchen next to the above-mentioned latrine, which for privacy was closed to a separate door. East one led from the room of service on the first floor of the neighboring tower, providing quick access to the monarch if necessary. This complicated layout was the result of up to four floors in the King’s Tower, none of which was on the same level as the first floor chambers of the building.

In the mid-fourteenth century, the roof truss was replaced in the queen’s chamber, and stone arcades supporting the roof were inserted. The queen’s chamber, like the previous ones, had a fireplace and a latrine, as well as two large windows from the courtyard side. Two more windows faced the opposite direction, one of them in the recess had a short passage leading to an bay window on the outer facade (probably a decorative oriel window recorded in 1285). The western part of the chamber underwent transformations in the early modern period. Originally, there was probably a passage leading to the Bakehouse Tower, in which the door to the queen’s chamber was also placed.

The ground floor of residential buildings of the upper ward was occupied in the same order as above: pantry, royal kitchen, passage leading to the eastern barbican and another pantry. The pantry was directly under the king’s great chamber. Although it was equipped with a fireplace, it was an ideal place for storage, close to the harbour and stairs to the first floor. In its corner there was also a passage to another pantry, located in the ground floor of the Chapel Tower. The kitchen was equipped inside the west wall with the largest fireplace in the castle, and shallow traces by the southern wall indicate the shelves and cabinets located there.

In the north-east tower a chapel was placed, intended for more private prayers of the king than the chapel at the lower ward. It consisted of a cylindrical nave located on the first floor, illuminated by slotted openings from the north and south, and an eastern recess in the thickness of the wall serving as the presbytery. This recess was illuminated by three large, narrow lancet windows and topped with a rib vault. Below the pointed windows, blind arcades in the form of seven niches crowned with trefoils were placed in the walls. Originally they housed the sedilia. The presbytery recess was separated by a large ogival arcade from the nave, with the arcades of the lower niches slightly protruded to the nave, supporting a wooden beam on which the crucifix was placed. The presbytery was flanked by two small rooms on the sides, also placed in the thickness of the tower’s wall. One of them probably played the role of sacristy, the other mayby was a lockable treasury, where the sacred vesels were kept. The chapel was directly connected to the king’s chamber, but interestingly behind the chapel there was also a small room from which the ruler could observe masses in isolation through a wall opening. This unusual solution was repeated only at Beaumaris Castle, but in Conwy it was expanded to include an adjacent latrine. Above the chapel in the tower was another chamber, heated by a fireplace and equipped with a large, two-light window. It probably served the castle’s chaplain. The ground floor of the tower did not have a residential function, but it was exceptionally well lit by the northern two-light window with seats and the western arrowslit. In the eastern part of the ground floor, the stairs in the thickness of the wall had an opening closed with wooden shutters, located above the passage to the harbor. Probably it was used to facilitate the transfer of goods from the boats, by means of a crane embedded in two holes.

The south-eastern tower was called the King’s Tower, although it probably contained rooms for servants. They were connected by narrow, dark passages and spiral stairs in the thickness of the wall with the royal chambers and kitchen, to not to disturb the peace of the ruler. In the heated by fireplace ground floor, the tower could be inhabited by a comptroller checking goods leaving the adjacent kitchen. He had access to a four-sided, barrel-vaulted and illuminated by a single slit chamber in the thickness of the wall, connected to the entrance passage. The main room on the ground floor was illuminated by a two-light window and a arrowslit opening directed at the eastern entrance to the castle. Below the ground floor there was a basement, lit by one small opening, accessible only by a ladder through an opening in the floor. The first floor was lit by a large two-light window overlooking the harbor and warmed by a simple fireplace. From this room, a short passage with a vestibule led to the latrine in the southern wall. For a change, the top floor, as unheated, was probably not intended for residential purposes, although its lighting was provided by a two-light window. As in the other towers, also here, the second floor was connected with the guards’ wall-walk.

The Bakehouse Tower originally lacked a massive spur at the base, which was only erected during the 19th-century renovation. It housed two residential chambers above the utility ground floor, occupied at least from the 16th century by a kitchen with a bread oven. It differed from the other southern towers in the lack of a basement. The first floor was connected to a small room by the queen’s chamber, while between the floors a passage in the thickness of the wall led from the staircase to the latrine in the curtain on the eastern side.

Opposite the Bakehouse Tower, from the town side, there was the Stockhouse Tower, although only the lowest level of the ground floor served as storage. The two upper floors were equipped with fireplace-heated living rooms, probably intended for the castle garrison. Like the Bakehouse Tower, the Stockhouse Tower was accessible only from the side of the upper ward and from the level of the defensive wall-walk connected to the second floor. The lighting on the first floor was provided by a two-light window with side seats. On its sides, two passages in the wall thickness led to latrines in slightly thickened adjacent curtains. The second floor was also illuminated by a two-light window and a smaller southern opening facing the wall-walk.

Current state

The Conwy Castle is now one of the best-known, best-preserved, deprived of early modern transformations and most-visited medieval monuments in Great Britain, along with town fortifications. By adding them to the list of world heritage, UNESCO considers Conwy to be one of the “finest examples of military architecture of the late 13th and early 14th century in Europe”. The only major damages to the walls in the form of a collapsed part of the Bakehouse Tower was removed during renovation. However, the completely destroyed economic buildings at the lower (outer) ward and most of the timber elements of the castle were not restored, leaving the remaining buildings unroofed. The castle is open to visitors from March 1 to June 30, daily from 9.30 to 17.00. In other dates, opening hours may change, so it is worth checking them on the official website of the castle here.

bibliography:

Ashbee J., Conwy Castle and Town Walls, Cardiff 2015.

Gravett C., The Castles of Edward I in Wales 1277-1307, Oxford 2007.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., Conwy Castle and Town Walls, Cardiff 2003.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Caernarvonshire, volume I: east, the Cantref of Arllechwedd and the Commote of Creuddyn, London 1956.