I was pleased to attend the book launch and museum exhibition of this stunning new book, the event held at the Newcastle Museum

This is a remarkable publication, given that it provides detailed and authoritative botanical monographs of 54 trees and shrubs that are endemic to the Hunter region, each one of which is accompanied by a full page scientific illustration.

The lead author, Dr. Stephen Bell, is probably the leading botanist in our region, having undertaken countless plant surveys over the last 25 years.

The fact that the other two co-authors, Christine Rockley and Dr. Anne Llewellyn, are both scientific illustrators, demonstrates the significance placed on the illustration component of this book. In fact as many as 20 different illustrators were used, all alumni of the Bachelor of Natural History programme at the University of Newcastle.

I was lucky enough to be photographed with the illustrator of Eucalyptus aenea, Candice Rogers.

One of the features of the launch was the stunning display of framed, enlarged prints of all the book’s illustrations, along with a video describing the process involved in the field surveying, collecting, cataloging, creating herbarium specimens, describing and illustrating each of the 54 species.

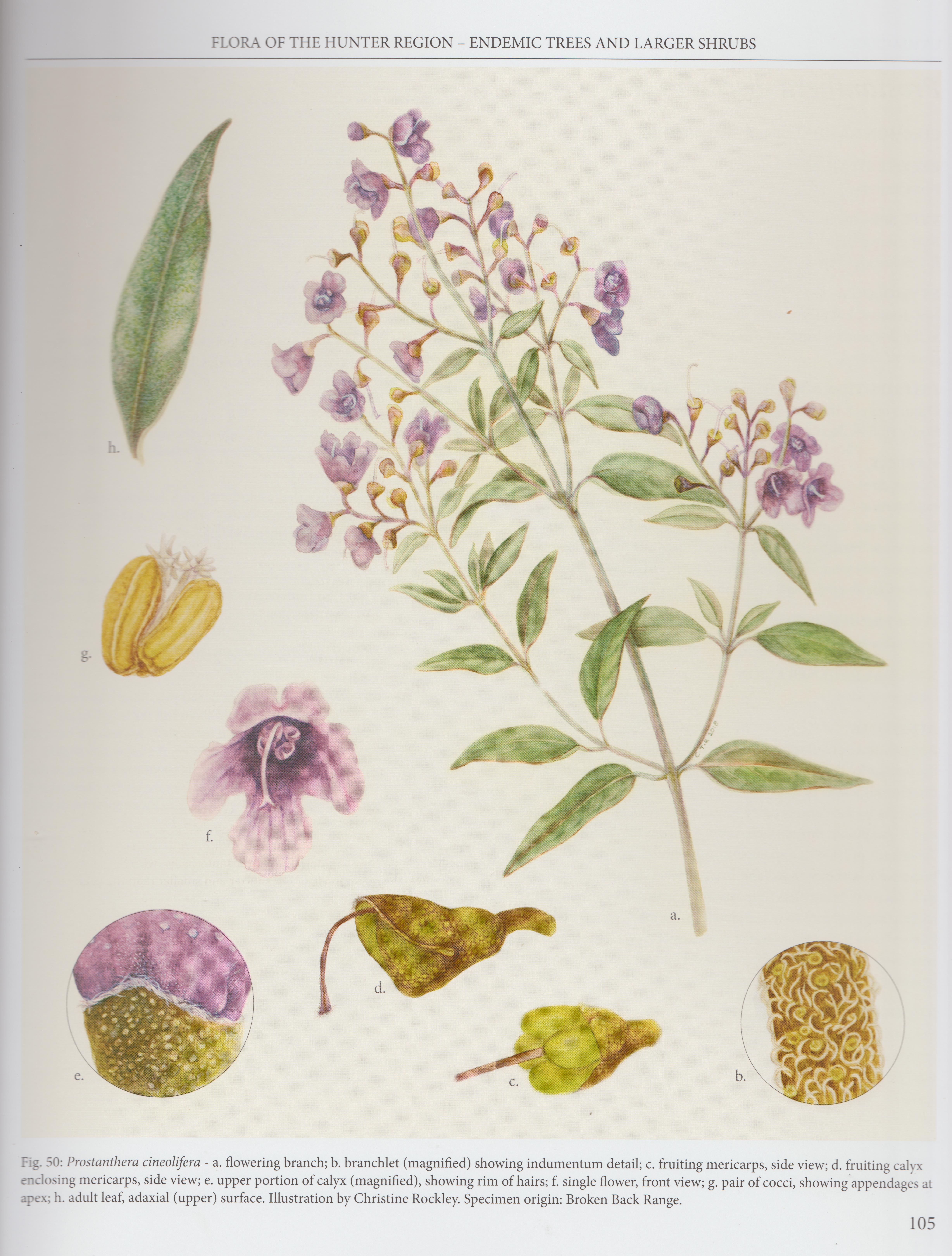

Each monograph contains the full nomenclature and etymology (origin of the botanical name), distribution (with map) and known reservation plus location of the “type” specimen, habitat including a long list of species it occurs with, flowering period, affinities with similar species and hints on differentiating them, key diagnostic features, conservation status, plus a protologue ie the original material associated with a newly published name, comprising detailed botanical descriptions.

There are numerous entries for species of interest from the point of view of their essential oil potential, but given that many of them are threatened or of limited distribution, they aren’t readily available for distillation. One such species is Prostanthera cineolifera, so named by Baker and Smith (pioneers of essential oil analysis of Australian plants) because it contains 1,8-cineole, giving off a eucalyptus-like fragrance. This species grows in a limited range centred around the Brokenback Range.

Additional information provided includes a glossary, an ecological and taxonomic bibliography, specimen collection locations plus coordinates (lat/long) for locations mentioned and conservation assessments for each species.

The full title is Flora of the Hunter Region. Endemic Trees and Larger Shrubs, published by CSIRO Clayton Vic, 2019. A second volume is in preparation, this will include herbs, grasses, orchids and other smaller plants. The recommended retail is Au$80.00 which is what I paid at the launch, however it can be purchased online for under $60.00.

This book is a must for native plant enthusiasts in the Hunter region, and for people anywhere who enjoy botanical artistry.

Vinca major – a uterine astringent

Vinca major – a uterine astringent