I’m excited to announce two of the most spectacular plant discoveries made so far in our reserves: two magnificent new species of Magnolia trees!

New species, Magnolia vargasiana ined. The stamens fell off onto the petals as the flower opened. A pollinating beetle is visible near the tip of the lower-right petal. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Everyone who knows about trees has heard of magnolias, and most people have seen the stately white-flowered Magnolia grandiflora tree, iconic symbol of the southeastern US, and widely grown around the world as an ornamental. It is hard to imagine that trees in this dramatic genus remain undiscovered. The discovery of two new magnolia species in one small area in the Rio Zunac Reserve is a testament to the very special character of the very wet Cordillera Abitagua, semi-isolated granite mountains separating the main body of the Andes from the immense flat Amazon basin. These two new magnolia species are on the same trail as the spectacular new tree Meriania aurata which was discovered here a few years ago.

The magnolia discoveries were first made by botanists John Clark (University of Alabama), David Neill (Universidad Estatal Amazonica), and their students, who came to our Rio Zunac field station in May 2014 to set up two research plots in the forest:

University of Alabama students, Universidad Estatal Amazonica students, Drs John Clark and David Neill, and our guards at our Rio Zunac field station. John is center bottom in white shirt, David is directly behind him. Photo: John Clark.

Their goal was to identify and tag every tree over 10 cm in diameter in each of these two quarter-hectare plots, one plot at 1850 m elevation and the other 2 km away at about 2000m elevation. In the process of identifying each tree in the two plots, they found a few individuals of trees that were vegetatively identifiable as magnolias. Some of them were among the biggest trees in the forest, but they were completely unknown to the local people, who did not have a name for them. Surprisingly, the magnolias in the first plot had quite different leaves from the ones in the second plot. Since there were no known magnolia species in the area at those elevations, David and John suspected these both might be new species. But flowers or fruits were needed in order to be sure.

Some of John Clark’s and David Neill’s students setting up the boundaries of their study plots in our Rio Zunac Reserve, assisted by EcoMinga’s Luis Recalde (light blue-gray shirt). Photo: John Clark.

John Clark is an expert on gesneriads (the African Violet family). While he was in our reserve with his students he discovered this new species of gesneriad, a Columnea, on the same trail as the magnolias and the Meriania aurata. Photo: John Clark.

Enter Antonio Vazquez, a Mexican scientist who is the world expert on Neotropical (New World tropical) magnolias. It just so happened that the Ecuadorian government had hired him as a visiting professor for a year at David Neill’s university, the Universidad Estatal Amazonica, just a few dozen kilometers from our reserve! So of course in September when he arrived in Ecuador Dr Vazquez went to the reserve to visit these magnolias, staying in our Rio Zunac field station. The plots with the magnolias are another day’s hike up from the station. Our guards Luis, Jesus, Santiago, and Fausto Recalde went with him and climbed the magnolia trees to search for flowers, fruits, and buds. They found a partially open flower on one tree, and a seed pod on another tree.

Flower pictures of the Neotropical magnolia species are always elusive, because the flowers open at night and close by morning. A given flower does this for two nights in a row, and on the third morning it remains open and the petals fall. Dr Vazquez and our crew had a stroke of luck with the flower of Magnolia vargasiana ined. They found a three-day-old flower that had been held together by insect webs, so that the petals didn’t fall off as they normally would. Here are some of their first photos of Magnolia vargasiana ined., before and after freeing the petals from the webs.

Left: The first flower ever seen of Magnolia vargasiana ined. was falling apart and held together by insect or spider webs. Right: The flower opened partially after loosening the webs. Photo: Luis Recalde/EcoMinga.

I was excited by these discoveries and made my own trip to the site to see them, with two students of Dr Vazquez and our forest caretakers/parabiologists Luis and Fausto Recalde. After much effort we found advanced buds of both species, which Luis and Fausto managed to collect by free-climbing these very tall trees.

To get the flower buds of these magnolias, Luis Recalde and Fausto Recalde climbed into the canopy. Here Luis climbs the hemiepiphyte root hanging from the right-hand side of the magnolia trunk; click to enlarge since he is so high he is almost invisible. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

As evening approached we watched the buds open. The bud from Magnolia llanganatensis ined. was damaged by insects and failed to open normally, but the bud from Magnolia vargasiana ined. opened beautifully by 5:00 pm, filling the area with a wonderful fruity smell.

We noticed that there were already four little beetles inside it, probably trapped there from the night before. We had discovered the pollinator of this magnolia! The beetles were coated with pollen and were rather tipsy. One fell off the flower, and when I tried to pick it up it jumped away as if spring-loaded. Later, as we looked at the photos, we saw that the hind legs of these tiny beetled were modified for powerful jumping. These observations suggested that these little guys belonged to the group of chrysomelid beetles known as the”flea beetles”.

This is the chrysomelid “flea beetle” (so named because of its powerful rear jumping legs) we found inside the magnolia flower as it opened. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Dr. Vazquez’s papers describing these new species were recently submitted to the appropriate journals. These exciting magnolia discoveries are part of a continent-wide trend. In the 1990s there were only four species of the genus Magnolia known from all of South America. As biological exploration in the neotropics has intensified in the last few decades, small numbers of new locally endemic Magnolia species have been turning up in remote locations all over the continent, as well as in Central America (see here and here for an exciting example in Mexico, in a reserve run by my friend Roberto Pedrazo; Dr Vazquez was also the expert who described those new species). Neighboring Colombia now has about 33 described species of Magnolia, almost all very localized and rare, many in danger of imminent extinction. For example M. espinallii is known from fewer than 50 individuals, and Magnolia wolfii is known from only five trees in one remnant patch of surviving forest surrounded by coffee plantations. Our own new species might very well be endemic to the Cordillera Abitagua. The two species seem to be very fussy about where they will grow, since they did not grow together in the same plots, even though the two plots were separated by only 2 km and about 200m of elevation.

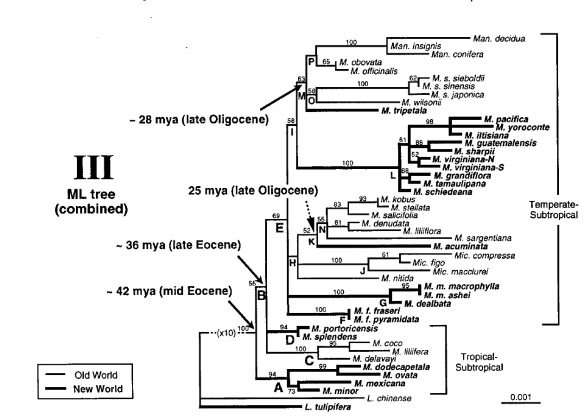

Apart from their conservation importance, these recent magnolia discoveries highlight some interesting biogeographic issues. Magnolia trees are an ancient lineage; their family goes back 100 million years, and trees that we might recognize as magnolia relatives lived alongside the dinosaurs. The South American lineage that our trees belong to Magnolia section Talauma, is the oldest lineage of the genus, diverging from the rest of the magnolias around 40 million years ago (Azuma et al 2001). The current theory is that these species got to South America via North America, which had close connections to Eurasia in the past. At that time North America would have had a tropical climate.

Phylogenetic tree of selected Magnolia species. M dodecapetala, M. ovata, M. mexicana, and M. minor represent the Neotropical species. Figure 1 from Azuma et al (2001), The molecular phylogeny of the Magnoliaceae: The biogeography of tropical and temperate disjunctions. American Journal of Botany 88(12): 2275–2285.

So when did our species, and the many other South American magnolias, diverge from each other? Are they all old species that began to diverge already in North America, or are they recent species that diverged close to their current locations? Figure 1 in Azuma et al (2001) seems to show that the South American and Lesser Antillean species of magnolia in the Talauma group diverged at least 9 million years ago. The Central American + Cuban species and South American + Lesser Antillean species they analyzed appear to have diverged about 20 million years ago. These divergences are earlier than the currently-accepted (but still somewhat uncertain) date when North America became connected to South America. So it might be that our species are very old, and last shared a common ancestor somewhere in North America, not in South America. This is a very different situation from most other within-genus evolutionary radiations here in the Andes, which are often only 2-3 million years old.

These kinds of questions will be discussed in detail at the upcoming First International Conference on Neotropical Magnoliaceae, which will be held right here in the shadow of the Cordillera Abitagua at the Universidad Estatal Amazonica from May 27 to June 2, 2015. Please write to Antonio Vazquez, jvazquez@cucba.udg.mx, for more information.

Many thanks to John Clark, David Neill, Antonio Vazquez, and their students for choosing to work in our reserve! And thanks to Luis, Fausto, Santiago, and Jesus Recalde for their enthusiasm in the field.

Lou Jost

www.loujost.com

www.ecominga.com

Please consider donating to keep these reserves protected.

Pingback: Two new scientific papers coauthored by EcoMinga staff | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Two more new frogs discovered in our Rio Zunac Reserve | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Exploring the “Forests in the Sky”: our new Rio Machay Reserve, east ridge | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Earth Day: High school students from Aldo Leopold’s alma mater spend a week in our Cerro Candelaria forest | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Second trip to our Rio Machay Reserve: Orchids, magnolias, insects, and toxic trees | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Our second new Magnolia is now officially described and published: Magnolia llanganatensis | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Melastomes 6: The day our eyes were opened, September 28 2014 | Fundacion EcoMinga