What is coastal prairie? There are various definitions by experts, but I like to describe this natural community as a perennial grassland on moister, cooler coastal hills, bluffs, terraces, and valleys that are influenced by Pacific coastal climates: summer fog and heavy winter rains. Many diverse wildflowers and some shrubs also inhabit this zone. Classically, this plant community was defined as running along the coast of California from northern Los Angeles County into Oregon, although a form of coastal prairie probably occupied the prehistoric southern California coast.

A Catalog of Coastal Prairie Grasses

These are some of the more commonly met grasses in coastal prairies and not an exhaustive list of species, although some are more characteristic of drier, inland grasslands that are often called “valley grassland” in older texts. The transition, however, is irregular, patchy, and discontinuous among species. Formerly abundant in an emerald carpet on the sea bluffs and coastal hills and valleys, only relicts of coastal prairie remain in parks and places where the bulldozers and hungry cattle herds can’t reach.

Washed in Fog

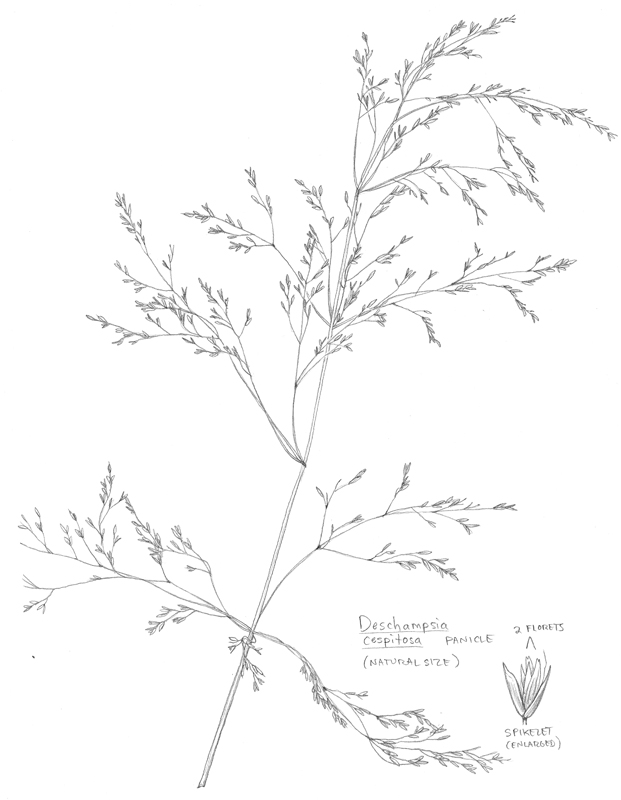

Tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia cespitosa) is a large northern coastal prairie bunchgrass of moist or marshy soils, or in ecotones with drier soils. Some forms are salt-tolerant. In the North Coast Ranges it enters Oregon oak (Quercus garryana) and California black oak (Q. Kelloggii) savanna and woodland, and range ecologist Beecher Crampton (1974) said it was once found in the Central Valley in marshes and along river edges. The subspecies Deschampsia cespitosa ssp. cespitosa is widespread along the coast and in mountain meadows of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Range, as well as the Great Basin.

The subspecies D. c. holciformis is the common coastal form. It was reported by Jepson (1901) in wet meadows and stream borders on the Oakland Hills and in San Francisco. Watson (1880) went further to say this large robust bunchgrass furnished good yields of hay in moist meadows of Oakland and San Francisco — this must be a lost habitat, dug up and covered with concrete and asphalt now.

At Point Reyes National Seashore, Marin County, large bunches of this grass dominate the relict coastal prairies behind dunes, in both dry areas and moist puddles. It is also common in Sierran meadows. This form is not salt tolerant, and is found on coastal prairie knolls behind the salt marshes at Point Reyes, mixing with Blue wildrye, Pacific reedgrass, and Red fescue. It is also called California hairgrass or coastal tufted hair grass

The salt-tolerant form D. c. ssp. beringensis grows in salt marshes on Point Reyes with saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) and picklweed (Salicornia sp.). It is a rarer coastal form in California.

Cattle grazing quickly eliminates it, leaving little trace of these moist meadow habitats. Only hints may remain under grazing pressure: inedible rushes (Juncus spp.) and native wild iris (Iris douglasiana) that can be seen in Point Reyes Pastoral Zone, signs of former more diverse meadow habitats that are now degraded. I found this grass within the elk fenced area, however, at Tomales Point.

Fountains of Fine Leaves

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) is an important northern coastal prairie bunchgrass, found continuously from San Mateo County northward. It is also abundant in open forests of the North Coast Range, and on the Modoc Plateau and interior West. A coastal California form, F. i. roemeri, is sometimes separated from the Great Basin and interior Northwest form (Amme 2003).

Graceful fountain-like bluish bunches with dense fine blades, I found these ornamental grasses common locally on north- and east-facing slopes and high ridgetops swept by summer fog in Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks, opposite the Golden Gate. The spikelets are less than 1.5 cm long and the lemmas have a 4 mm-long awn, separating it from bromes which have spikelets longer than 1.5 cm, and from Poas, which are awnless or very weakly awned. Idaho fescue can have reddish culm bases like Red fescue, but the culms are only slightly bent at the base. Red fescue culm bases are very bent (decumbent) before they straighten out and grow upward.

Along Nimitz Way the plants made up full bunches that in an ungrazed state sometimes became large and mounded into mushroom shapes. In February the bunches were dark green in color, and walking among them was a different experience than walking though an annual grassland: the fescues were large and almost shrub-like so that I had to step over them or between them, and the intervening ground was spongy from dense Diego bentgrass. In many places voles had made smooth runways and tunnels irregularly between the bunches. This patch had about 100 fescue bunches growing near a hilltop, with San Fransisco Bay reflecting the blue sky to the west. By April all the bunches flowered, putting out 2-foot high seed panicles, varying in color with each plant — some were glaucous-green, others yellowish, and some pastel-brown. Most panicles were closed, but some were open and feathery. Mixing in were white yarrow (Achillea millefolium), wild pea (Lathyrus sp.), wild cucumber (Marah fabacea), checker (Sidalcea malvaeflora), phacelia (Phacelia californica), and soap plant (Chlorogalum pomeridianum).

Beautiful remnants of this type of coastal prairie can be seen in higher ground at Point Reyes National Seashore in Marin County, as at L Ranch on the farthest edges of dairy cattle pastures that are too far for the cows to access from the barns. Thus they are ungrazed. Large areas of the park unit may have held this species on well-drained uplands, now eliminated by heavy livestock grazing.

The farthest inland in Contra Costa County that I have seen Idaho fescue is on Fossil Ridge in Mount Diablo State Park on a moist north-facing slope near Coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), Bays (Umbellularia californica), and Buckeyes (Aesculus californicus). Go to San Bruno Mountain south of San Francisco, in San Mateo County, to find more good stands of this grass.

Surprises are always in store for the seeker, as I found one day while looking for native grasses along backroads in southern interior Monterey County. I happened upon a large stand of Idaho fescue growing in a Blue oak (Q. douglasii) savanna in a dry valley — unusual habitat for this bunchgrass in California.

These bunchgrasses need protection from livestock grazing, as they are tender and palatable, and so are the first to be grazed out.

Native Lawn

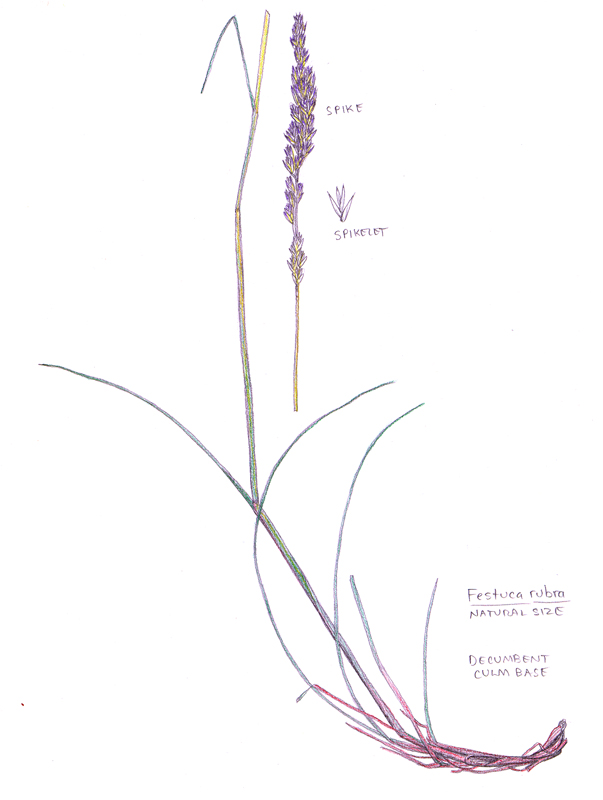

Red fescue (Festuca rubra) is a sod grass growing by short rhizomes into small patches — I have seen them tuft-like to a yard across and spreading. The plants have red at the culm bases — a good way to identify this grass. It is found in the summer-cool areas of the Coast Range from Monterey County northward, in coastal prairies, mountain meadows, open grassy hills, sandy coastal places, bogs, and saltmarsh edges (Howell 1970). Hike in Mount Tamalpais State Park in Marin County and look on open slopes and potrero meadows for Red fescue.

Along San Pablo Ridge in the East Bay mats of Red fescue grow on moist north- and east-facing slopes and foggy, windy ridegtops. Here they often have no awns or awns only 1 mm long. In other areas the awns grow to 4 mm. Unlike many other native grasses that have scabrous (rough) leaves when you run your hand along them, Red fescue has smooth blades that are usually rolled up (involute).

Relict Red fescue mixes with Idaho fescue on far pasture corners at L Ranch in Point Reyes National Seashore, where dairy cows do not graze. These areas should be preserved as reference sites for seed collection and as restoration guides, to aid in rewilding the coastal prairie to a wider area at Point Reyes National Seashore and Golden Gate National Recreation Area, once livestock are reduced or removed. I also see Red Fescue in the elk-grazed Tomales Point Tule Elk Reserve.

Northwest Bunchgrass

Pacific reedgrass (Calamagrostis nutkaensis) is a coarse, thick-leaved, large bunchgrass that lives on the direct coast with all its fury of ocean winds, salt air, cold rain, and foggy summer moisture. This tough bunchgrass has to withstand strong salt-laden winter winds directly off the ocean, and it appears to thrive here.

At Point Reyes National Seashore I have found this native grass holding on as a relict on roadsides along the road that traverses E Ranch in the Pastoral Zone — an area heavily grazed with dairy cattle that I observed to cause heavy erosion and trailing, eliminating any native grasses in the fenced pastures on National Park Service lands. Within the tule elk fenced area on Tomales Point, I found large scattered bunches of Pacific reedgrass on hilltop coastal prairie, doing fine with the light elk use.

I also found a relict Pacific reedgrass stand in an exclosure fenced off from all grazing (for a weather station?) around the vicinity of C and D Ranches, where the coarse bunchgrasses thrived along with the rare native western dog violet (Viola adunca), host species to the Myrtle’s silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene myrtleae). Outside the fences, the grassland was grazed heavily, eliminating these native species. and only introduced European annual grasses grew–mostly low quality Mediterranean ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus).

Adapted to Elk

California oatgrass (Danthonia californica) is not a true oat but its seeds have a slight resemblance. Found coastally these grasses grew formerly from the vicinity of Los Angeles north to British Columbia. They need adequate soil moisture, so are quite rare in the inner Coast Ranges, Central Valley, and Sierra Foothills, although they have been reported from wet meadows and seeps in these regions (Munz and Keck 1959). Jepson (1901) said they were the prevalent grass on well-drained uplands and hills along the coast. In the drier North Coast Range grasslands they formed a mesic community on swales, wet meadows, and springs in open areas with Meadow barley, Sedge (Carex densa), Spikerush (Eleocharis acrostachya), and rush (Juncus spp.).

In Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks I saw California oatgrass fairly commonly in moist bogs on grassy flats and over the drier ridges of the summer-fog zone. The flat bunches with culms splaying out in different directions towards the ground contrasted with the tall straighter needlegrass bunches. See this grass along Nimitz Way in Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks, Contra Costa County. At Point Pinole Regional Shoreline, oatgrass bunches mixed evenly with Purple needlegrass over the flats in back of the bay marshes. Elsewhere in the Coast Range I found it common in wet low areas near willows, and on valley floors right up to edges of vernal pools in Sonoma Valley Regional Park (Sonoma County). At Anadelle State Park (Sonoma County) I saw some on bald hills with Purple needlegrass, surrounded by California black oak (Quercus kelloggii), Coast live oak, and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii); oatgrass became abundant in lower valleys here.

This prostrate “pre-trampled” growth form aids the oatgrasses to resist elk grazing. The culms arch outward and down, and in the extreme the culms spread flat out sideways along the ground away from hungry ungulate mouths. Each node on the culm puts out flowering spikes, and the culms fall off easily, perhaps an adaptation to allow passing hoofed animals to kick them away and spread the seeds far from the plant. The bunches become smaller in basal diameter with increased grazing, around 4 to 5 inches. But sheep can chew the low nodes off with their small incisors, sometimes killing the plants if allowed to graze year-long. Cattle grazing will also eliminate these natives, as.

I should qualify this with the observation that one tule elk weighs around 500-600 pounds with a relatively narrow muzzle. A typical dairy or beef cow can weigh twice this much, and a bull over 2,000 pounds, with wider muzzles to gobble up forage. The trampling impact of cattle therefore can be much larger than native elk and deer. California oatgrasses cannot withstand this much impact, and so have vanished from much of the California coast under domestic livestock grazing regimes.

California oatgrass is cleistogamous–more seeds are contained within the sheath of the culm, and these seeds have no open pollination. Each node puts out flower spikes, and culms are easily kicked off with passing elk herds, which spreads the seeds.

On Tomales Point within the tule elk fenced area, I found California oatgrass fairly common and not trampled or overgrazed.

In ungrazed parts of Wildcat canyon I noticed the bunches growing large, often to 10 inches in basal diameter, many with more erect culms, nitting together to form a continuous dense grass layer. They form a “flatter” grassland than other bunchgrasses. But I have also seen ecotypes of the grass that are tall and erect, as at Coyote Hills Regional Park in Alameda County, where no grazing takes place.

Soft Deer Beds

Diego bentgrass or Thingrass (Agrostis diegoensis or pallens — experts disagree on its classification) is fairly common in coastal areas in open grassland, mixing with both Purple needlegrass and coastal prairie species. It is a rhizomatous native, forming small loose patches usually less than 6 to 10 feet across and leaves around 6 to 8 inches high, perfect nesting spots for deer to curl up and sleep on. The delicate lawn-patches send up only small thin seedheads.

Around the outer Coast Range I found bentgrass forming loose turfs at the edge of Coast live oak groves and within their shade, in the open on slopes where fog moistened them, and forest openings in the Douglas fir-redwood belt. Along the Wildcat Peak Trail in Tilden Regional Park, I found Diego bentgrass in large patches, filling swales, and growing on slopes and ridgetops in the summer fog zone. In March it formed beautifully soft, green, meadow-like patches of uniform blades, contrasting with the surroundung taller, uneven Purple needlegrass bunches.

Inland away from the fog belt it recedes to the cover of thickets and woodlands. In Pine Canyon, Mount Diablo State Park, for instance, I saw greenish scraggly patches in June of 1985 to be fairly common under Blue oak woodlands, never forming dense meadows, but with thin tufts of leaves along rhizomes. In southern California it was reported occasionally along streams on the plains, and in dry grasslands of the mountain foothills (Davidson and Moxley 1923, Lathrop and Thorne 1968). Jepson (1901) called it “one of our most abundant native grasses,” in the shade of bushes on dry hillsides of the Coast Ranges from San Diego to Sonoma County.

But constant livestock grazing eliminated it quickly, and relicts can be found only in the protection of places like low shrubs and steep banks, as well as in ungrazed parks. I found a patch of this grass within the tule elk fenced area on Tomales Point, Point Reyes National Seashore, no grazed out by the elk.

Other California endemic bentgrasses that are found in coastal prairie and cliffs include Agrostis blasdalei and A. densiflora.

Meadow Mixes

A common moist-soil bunchgrass of lowlands, mountain meadows, swales, seeps, flats by streams, and open bogs is Meadow barley (Hordeum brachyantherum). It tolerates subalkaline areas of drying pools with intermittent flooding. Its narrow spike seedheads make dark brown-purple textures in wet meadows.

In the East Bay hills this bunchgrass formed dense patches in open boggy areas of grasslands, whether in valleys or on ridgetop saddles or bowls. It mixed with sedges (Carex spp.) and rushes (Juncus spp.), as well as showy Yellow monkeyflowers (Mimulus guttatus). I have seen it on moist flats, meeting Purple needlegrasses which grew on drier flats. In other areas it formed extensive stands in muddy spring outflows mixing with Creeping wildrye, on silty floodplains, drying pool margins, and flats by willows. On sloping grasslands east of the Berkeley-Richmond hills I walked among very common Meadow barley fields which were especially thick in dry mud that May; California buttercups (Ranunculus californicus), blue-eyed grass (Sisyrhinchium bellum), harvest brodiaea (Brodiaea elegans), grass nut (B. laxa) and wild onion (Allium unifolium) grew with it. If too heavily grazed and trampled by cattle and for too long, it will disappear.

Along Nimitz Wat in Tilden Regional Park (Contra Costa County), I have observed populations of this grass fluctuate over several years on coastal prairie hill slopes and swales, increasing in rainy years, and decreasing during drought years.

A form grows on coastal terraces in southern San Luis Obispo County that has flat culms (stems).

At South Beach in Point Reyes National Seashore, meadow barley can be found in ungrazed coastal prairies and swales mixing with rush (Juncus patens), coastal tufted hairgrass, and California oatgrass. It also grows in the elk-grazed Tomales Point fenced area in open prairie.

In the dry inner Coast Ranges I found it on moist flats along streams and in valley vernal pools. In the Delta I found dense bunches on a roadbank next to a willow slough in San Joaquin County, a probable relict of former abundance. In another trip I came across a population of Meadow barley bunches with very long-awned beautiful wavy spikes next to tule marshes near Los Banos (Merced County).

No doubt the plants were taken by elk as they searched for the moist green grass patches in the dry summer months.

Wild rye

Blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus) is an abundant bunchgrass in western North America below 7,500 feet (Munz and Keck 1959). It occurs in conifer forests, oak woodlands, riparian groves, chaparral, and in grasslands on rich loamy soil. On the outer Coast Ranges I have seen it particularly dense on open cool north-facing slopes; it became less frequent in the interior Coast Ranges, Sierra Foothills, and southern California, often retreating to the mesic spots under oaks, and along streambanks, springs, and floodmargins. In the Central Valley it was apparently not common, but in Jepson Prairie Preserve (Solano County) it can still be found in open grasslands on deep soils. In the East Bay hills I discovered it to be abundant and widespread on hills and valley flats, both in the open and in the cover of Coast live oak woodlands. It formed dense tall stands on west slopes facing the fog-carrying winds. After a wet winter in the Mayacmas Mountains of Lake County I saw Blue wildrye growing lush in June with Purple needlegrass in a Valley oak savanna, covering the ground 100%. Visit Fort Tejon State Historic Park, Kern County, and look under the oak edges and hillslopes for this grass.

Its bunches contain dense fairly wide blades (often 6 to 8 mm), varying in color from deep green to glaucous. Numerous spike-culms stretch up that survive well into winter as they turn gray with the cold. I have noted annual variation in the density of spikes with rainfall in Tilden Park: wet years produced lusher stands.

Once I collected seeds from the waist-high spike-stems by knocking them into a basket as the native people had done, then attempted to grind the cured seeds into flour. Although delicious, I was not expert at separating the grain from the chaff — grinding on a rock metate and throwing the mess up into the breezes allowed the heavier edible parts to fall back down. But my resulting pinole was quite fibrous! Singeing off the glumes, awns, and lemmas with hot coals in a vigorously shaken pan might produce more “professional“ results.

Cattle will graze the wildryes, even when dry. But anything more than light grazing will eliminate them or reduce them to the cover of brush. The plants will, however, quickly invade bare areas with fast-growing vigorous seedlings that mature in one season. It is fairly common in the tule elk-grazed Tomales Point fenced area on Point Reyes.

I found the largely coastal subspecies Elymus glaucus ssp. virescens in a swale with sedges (Carex sp.) in dunes and coastal prairie at South Beach in Point Reyes National Seashore. This form has no awns.

Green Valleys

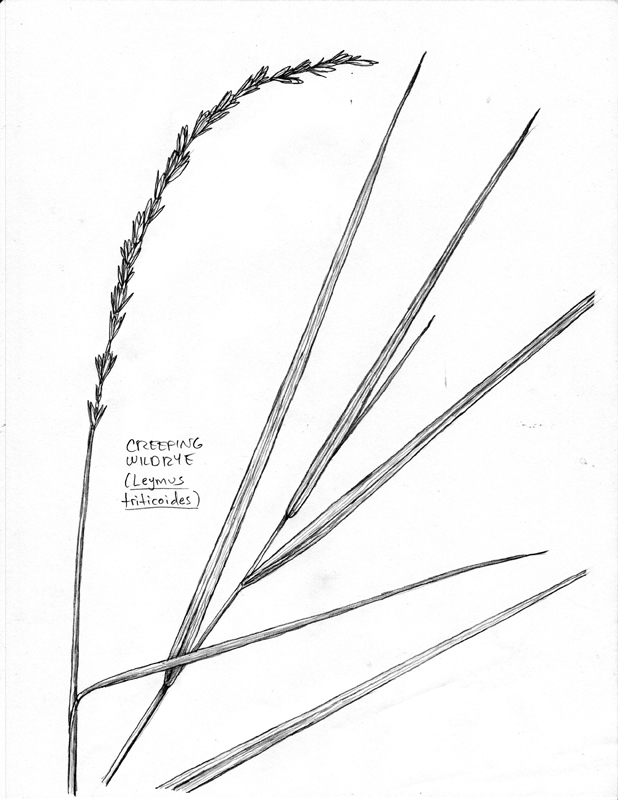

Creeping wildrye (Elymus triticoides, formerly Leymus triticoides) is one of the most important native grasses, once covering much of the valley floors, floodplains, marsh edges, basins, and hill-swales in the state. It is not a bunchgrass, but rhizomatous, spreading out by vegetative runners and roots to form wide patches sometimes an acre or more in extent — thus the “creeping” growth form. Continuous swards were made up of many plants that covered whole valleys. It needs fairly deep soil, but is tolerant of alkaline and saline conditions. On the coastal fog belt it grows up on hill slopes and ridegtops in large round patches. Before European arrival it probably covered hundreds of thousands of acres of bottomlands all over the state in the Central Valley and Coast Range valleys, while the needlegrass-bluegrass community interfingered with it on drier flats and slopes.

In Napa Valley, for example, I saw Creeping wildrye relict patches so commonly on the floor of the valley where vinyards had not excluded them that I thought this grass must have originally covered much of the flatland here. Creeping wildrye also lined creeks, formed an understory in riparian woodlands, grew around quiet backwater sloughs, and fringed both salt- and freshwater marshes. One could call it “friend of the Valley oak, friend of the Cottonwood.”

In southern California, patches grew on valley floors around Western sycamore (Platanus racemosa). I searched under spreading Valley oaks and shrubby native walnuts in Woodland Hills on the edge of the San Fernando Valley (Los Angeles County), and found a remnant of Creeping wildrye growing in a large green patch on an open flat; Highway 101 roared noisily nearby. Early botanists described this spreading grass filling bottomlands and alkaline places in southern California (Davidson and Moxley 1923)

This is another plant that ignores regional borders and climates. I could get an idea of its possible contribution to the flora by traveling to the Great Basin where it is still extensive and not hidden from view by a crush of alien weeds. Stopping in various places along Highway 395 from Bishop to Oregon and out into Nevada, I detected little difference in its growth pattern between these basin and range meadows and the oak savannas of west-central California. The green or bluish tall wildrye “lawns” filled most creekbottoms around willows, and formed abundant large patches in wide valleys. Back in western California I found it in similar situations, hugging the edges of willow thickets, filling canyon bottoms, valley floors, “hogwallows,” moist slopes, gullies, and arroyos.

The blades are flat, to 6 mm wide. Though spreading vegetatively, the plants do put out seed-spikes, often curving or drooping. At Point Pinole Regional Shoreline (Contra Costa County), large leafy patches about 2 feet tall covered almost a quarter acre each, widely scattered among grassland flats of Purple needlegrass and California oatgrass. Four-foot tall stands full of robust, nodding culms grew above cliffs creating a beautiful scene as they silhouetted against the smooth pastel blue-pink-orange bay waters shimmering at sunset. Go to Cosumnes River Preserve in Sacramento County to see acres of this grass next to Valley oaks. It is also the dominant grass in the open floodplain and oak woodland understory at Ancil Hoffman Park along the American River in Sacramento.

At Point Reyes National Seashore it grows in low areas in back of coastal dunes as at South Beach and Kehoe Beach, in ungrazed areas with no domestic livestock. On the Tomales Point tule elk fenced area, I saw an elk trail through a beautiful, ungrazed green patch of Creeping wildrye in a ravine bottom near a marsh; I didn’t see these kind of native grass stands in the Pastoral Zone with dairies and cattle ranches.

Although somewhat coarse, cattle and horses will dine on it — I have noticed all the tops “mowed off” by cattle when it was green in July on swales, slopes, and around springs. By the end of the dry season in October cattle will graze it down heavily. It seemed to be adapted to moderate grazing by elk as the herds gathered in the summer-green moist grasslands dominated by this plant in lowlands. When the upland bunchgrasslands were dry, Creeping wildrye remained lush into September. I have seen it respond well to mowing along roadsides in May, producing juicy new green growth by June. I have also seen it survive an episode of ploughing, the rhizomes able to continue growth. On rolling Valley oak grassland hills of the southern part of Mount Diablo State Park on Stone Valley Road this grass is dominant on ungrazed valley floors, filling ravines, extending up slopes three-quarters to near the low ridgetops. But it is absent on overgrazed parts just outside the fences, which appear to be 99% non-native plants.

I watched Tule elk graze lightly on green Creeping wildrye in April at San Luis National Wildlife Refuge in the San Joaquin Valley marsh edges (Merced County).

The rarer California endemic, Pacific wildrye (Elymus pacificus), grows in coastal areas from Los Angeles County northward. I found it in Pointv Reyes National Seashore on old sand dunes with a lot of organic matter at South Beach, and in swales. It is similar to E. triticoides but has darker green blades here, small, compressed seed spikes two inches long.

The large, tall Giant wildrye (Elymus condensatus) grows along the southern California coast.

Western Prairie Grass

Prairie junegrass (Koeleria macrantha) is a beautiful neat bunch with compact spikes of seeds. It ignores all boundaries, equally at home across Eurasia, on the Great Plains, over the West on desert mountain ranges, and into California unhindered by snow or arid summers. It is found in open grasslands, savannas, conifer forests, and mountain meadows up to 11,500 feet (Munz and Keck 1959). In California grasslands I found it common near the coast but also in the less severely arid interior Coast Ranges and Sierra Foothills. Botanist Willis Jepson (1901) called it common on dry hills and sandy tracts in our state. It was said to be very common in southern California grasslands (Abrams 1917).

In Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks relict tufts grow uncommonly and prefer north-facing slopes and ridgetops in coastal prairie, but they become more frequent on poorer soils of chert and shale, perhaps due to reduced competition with introduced annual grasses. They mix with Purple needlegrass in places, as well as Idaho fescue and Diego bentgrass. At Las Trampas Regional Park, Contra Costa County, I found junegrass bunches in grassy openings among live oak and blue oak groves in valley grassland; on open hilltops and ridges mixing with Purple needlegrass, Small-flowered melic, and Blue wildrye; on northeast-facing slopes in oak savanna; and in open blue oak savanna on drier southwest-facing slopes. I also saw it forming dense stands around Oak Knoll picnic area at Mount Diablo State Park. It grew under Blue oaks elsewhere in the park.

On Terra Linda Ridge in Marin County, I found some Prairie junegrass growing on an east-facing slop with California oatgrass, Foothill needlegrass, and rush (Juncus tenuis). At Austin Creek State Park in Sonoma County, it grows with Idaho fescue and Blue wildrye on north-facing slopes.

The spikelets and seeds of Prairie junegrass are “scaberulous,” with only a fine short hairy covering. They have no stiff hairs or awns, and so are not well adapted for transport by animal or wind; I have seen piles of dropped seeds around the bunches in late June. Therefore they may have only established in areas around the parent plant, producing the small patchy distribution of bunches that I often found. Groups of this bunchgrass are very good at allowing native wildflowers room to thrive. The output of seedheads varies with annual rainfall, as I watched the same bunch along Nimitz Way in Tilden Park: in June 1986 the plant had 7 seed spikes, compared with only 2 the previous year.

This species is one of the most eagerly sought forage grasses by livestock with its soft, crowded long basal leaves (which are around 2 to 3 mm wide). When green, sheep, cattle and horses seek it out in preference to many more abundant range plants. Elk will take it readily. When subjected to long grazing pressure in fenced pastures it dies out; thus it may have been more widespread in Old California than the relict evidence indicates due to the ubiquity of domestic livestock.

Mountain and Valley Tufts

A widespread group of western grasses with many variant forms, I found California bromegrass (Bromus carinatus) and Mountain bromegrass (B. marginatus) to be common broad-leaved bunchgrasses in the open prairies of the Coast Range, although inland of the fog belt they occurred as a rule on deep rich moist soils or under the shade of oak savannas and foothill woodlands. Current taxonomy favors merging these two species as B. marginatus. The wide blades (usually to 5 to 9 mm) contrasted in a rich varied texture with the narrower leaves of the needlegrasses with which they mixed. I often saw bromes growing in broad pure patches in the Coast Range, several yards square.

California brome can handle drier habitats than Mountain brome. I have seen tall weeping panicles of California brome growing under Valley oaks in warm Coast Range valleys, and in the Central Valley at places like Natomas Oaks Park in Sacramento by the American River. It was fairly common in southern California grasslands before the cities (Abrams 1917). Mountain brome can be common in coastal prairie, although usually not on the immediate ocean front.

In April the Mountain brome seed-panicles are rich green or tinged purple. The multiple-seeded bromegrass spikelets shatter when dry, and the awned, scabrous florets catch easily on animal fur for transport. Along Nimitz Way in Tilden Regional Park I noticed that Mountain brome stands were usually open enough to allow many wildflowers to grow among them: lomatium, checker, grass nut, ookow, and wild pea. But when the spacing between bunches was less than 6 inches, only the tall yarrows and fiddlenecks mixed in. In moist areas on good years I have occasionally seen culms of both California and Mountain brome culms growing to 5 and 6 feet tall.

California brome is usually annual, although biennial or occasionally perennial forms occur, both of which I have found growing on Bay Area ridge grasslands and flats. Its leaves and culms are scabrous (having rough short stiff hairs), or with a few scattered long hairs, or even glabrous (smooth). Often it appears more stemmy with less leaves at the base, growing at most in thin tufts. The sheaths are smooth.

Mountain brome is the perennial bunch-form, and has pilose leaves (with soft-hairs), sheaths, and culms. The Jepson manual (Hickman 1993) combines these two into one species, although recent systematic work keeps them separate (Reiner 2007). I have looked at plants that seem to be hybrids, with characters of both types, such as very pilose plants growing in an annual-like habit, or large bunches with glabrous sheaths and scabrous blades. On other sites the two forms grow together keeping their respective shapes. Perhaps these grasses are in an active stage of evolution, fluctuating in abundance and characters with dry climatic phases (which perhaps favored California brome) and Little Ice Age conditions (when Mountain brome thrived). A confusing array of intermediates has resulted.

Watch out for the similar Bromus stamineus, an exotic from Chile, which has wider lemmas (2.5 to 3 mm) with wing-like margins, and Eurasian B. japonicus, which has more cylindrical spikelets.

These bromes are some of the most palatable native grasses with their soft blades, and thus they disappear on overgrazed fenced ranges. Bromes can withstand moderate grazing, and will easily colonize bare areas with a horde of new seedlings. Out of all the native grasses I have noted Mountain brome leaves to be the most favored by hungry Black-tailed deer. In May I have watched sparrows land on the panicles to pluck the seeds. It is common in stands in coastal prairie within the fenced Tomales Point tule elk reserve at Point Reyes National Seashore.

Maritime Bluegrass

Also called Douglas bluegrass or Sand dune bluegrass (Poa douglasii), this species grows along the California coast and is endemic to the state. I found it at Point Reyes National Seashore in beach and dune areas mixing with coastal prairie in sandy places. It has short, rounded little seed-heads.

Delicate Needlegrass

The most coastal needlegrass in California, I include this species under coastal prairie, as it favors moister, cooler locations than other needlegrasses. Foothill needlegrass (Stipa lepida, formerly Nassella l.) has short, delicate, straight awns, often bronze, green, or purple in spring color. The dense blades appear finer than Purple needlegrass. In May the color of the bunches is a slightly different shade of green than Purple needlegrass. By October the dry bunches turn light yellowish.

Foothill needlegrass mixes commonly with Purple needlegrass or forms small pure stands on the open ridge grasslands of Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks near the coast. It also grows in the shade of live oaks. Inland, as at Mount Diablo State Park (Contra Costa County), I saw it fairly common in the shade of chaparral. At Sunol Regional Park (Alameda County), I discovered a few bunches along an open arroyo on a grassy slope near Valley oaks on the McKorkle Trail. In Agoura Hills and in the Santa Monica Mountains (Los Angeles County) I found both Foothill and Purple needlegrasses in sage scrub.

I discussed native grassland ecology with restorationist Tim Gordon in 1984 while we gazed on beautiful hill slopes covered with Foothill needlegrass on Albany Hill in El Cerrito, not far from the plaza where I had imagined grizzly bears feeding on acorns. The “little hill” was an urban island of open land he was helping to restore at the time. An Ohlone acorn mortar rock lay under live oaks by a creek at the base of the hill, and shellmounds lined the bayshore nearby. He told of watching pools of water form between the bunches during rains, held up by little grass dams between the plants, allowing much more water to seep into the soil than in annual grasslands. The extensive root systems of the bunchgrasses helped stabilize the soil, and perhaps in the past aided in preventing extensive landslides. Tim thought that this water seeping down into the hill bunchgrasslands might take a year to reach the bottom slopes, and might have produced many springs. Some local creeks may have flowed longer into the dry season with this increased water storage capacity of the uplands, and may have been perennial instead of intermittent, positively affecting the salmon and steelhead entering these waters. We can only speculate about such lost interrelations.

Cattle eat this grass with relish, and in moderately to heavily grazed ranges it will “retreat” to the cover of Coyote bushes and other hiding places, then disappear utterly with more grazing.

(See illustration below)

Valley Grassland Species

These native grasses I include here because they formed the interior more arid-adpated grasslands of California, that inter-fingered with coastal prairie, transitioning away from the Pacific ocean fog belt. Although along the southern California coast, from Los Angeles to San Diego, these grasses probably reached the beaches and sea cliffs along with other more arid-adapted plants. Today remnants still remain in places protected from livestock grazing impacts and urbanization developments.

Purple and Gold

The state grass of California, Purple needlegrass (Stips pulchra, formerly Nassella p.) was called “beargrass” in the past apparently due to the appetite of grizzlies for its green blades. It is not what I think of as a true coastal prairie species, but is very widespread, so interfingers with and mixes with Idaho fescue, red fuscue, and other coastal prairie plants, and will grow close to the Pacific edge on drier hills and ridges.

Through my travels I found it to be the dominant grass over much of the state’s native open landscapes, often appearing in exotic annual grasslands that have not been completely degraded. The California grassland was one of the few in North America dominated by needlegrasses, and Purple neddlegrass and its relatives Foothill needlegrass (S. lepida) and Nodding needlegrass (S. cernua) are endemic to this region. Stipa pulchra can still be found below 5,000 feet from northern Baja California to Humboldt County, and in all grasslands except the driest parts of the San Joaquin Valley.

Purple needlegrass once covered vast areas of slopes and plains in southern California according to early botanists (Davidson and Moxley 1923). It reached the coast in much of the state, but in the arid inner South Coast Ranges was generally replaced by Nodding needlegrass. Preferring full sun, Purple needlegrass was also found in oak savanna where woody cover did not exceed 80% (Bartolome and Gemmill 1981).

I found remarkably well-preserved prairies of needlegrass on slopes in the Coast Range in back of the East Bay during my explorations.

On a west-facing slope in Wildcat Canyon Regional Park (Contra Costa County), I pondered the lush potential for growth of wildflowers in an ungrazed bunchgrassland. Purple needlegrasses commonly clothed this slope in January 1985, with 1 to 3 feet separating each bunch. Forming thick little blankets of green around them were Dove lupine rosettes (Lupinus bicolor) a few inches high, waiting for spring to flower. The lupines became dense only where the ground was bare along trails, on old gopher mounds, or around the needlegrass bunches. They did not grow where introduced annual grasses or tall old leaf litter crowded them out of light and water. The lupines grew right up to the bases of the bunchgrasses if the ground was bare, but if annual grass seedlings were sprouting the lupines were absent or widely scattered. A few other wildflower rosettes grew with the needlegrasses here: wild pea (Lathyrus polyphyllus) and lotus (Lotus humistratus).

That April I studied the competition faced by natives along Nimitz Way in the same park. I found that Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bellum) mingled well with Purple needlegrass when the bunches were spaced about a foot apart, but if introduced annual grasses filled in the spaces and grew higher than 6 inches they often dropped out. Wild pea and American vetch (Vicia americana) did well in a wide range of situations because they could stretch taller, to 1.5 feet to get the sunlight in needlegrass patches. California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) favored disturbed ground, places where I imagined elk to bed down or burrowing kangaroo rat precincts to have existed. Poppies were fairly common between open needlegrass bunches. White yarrows (Achillea millefolium) were one of the few natives that could compete with tall exotic grasses, as they could reach 2 feet and often formed their own perennial patches within the grassland; they grew well with needlegrass too. Yellowcarrots (Lomatium utriculatum) did better with shorter annuals, and were conspicuous among Purple needlegrasses. Mule ears (Wyethia angustifolia) fared well among annual grasses, but seemed most common in Stipa fields.

In contrast, other stable, ungrazed patches of pure Purple needlegrass nearby had nearly 100% cover, with no ground visible in between. The bunches touched each other and only a few other plants could grow with them. Summer fog bathed these ridges, so a transition to true coastal prairie.

But I concluded that in a reconstruction of this grassland before the masses of Mediterranean annuals invaded, many species of wildflowers and native grasses would be more common on this coastal ridge. The most widespread habitat would have been occupied by Purple needlegrass, spaced about 1 foot apart, with bare ground around them. A variety of wildflowers grew with the bunches, as well as other native grasses growing singly such as One-sided bluegrass, Prairie junegrass, and California melic (Melica californica). Large stands of Mountain brome grew in many places, allowing a smaller number of wildflowers to grow with them, such as yarrow. Patches of California melic were scattered. Even though wildflowers would have been more common, in many places they may not have been as visible on the hills at a distance because of the taller, relatively close flowering panicles of the bunchgrasses partially covering them. Brighter patches of flowers would have colored drier areas, and sites disturbed from grazing or fire.

Inland at Lake Berryessa Recreation Area (Napa County) in the dry interior North Coast Range the scene was similar. In June of 1989 I found Purple needlegrass abundant all over the flats and gentle slopes near the picnic areas, which were mowed periodically but not grazed except by deer herds. Sometimes the individual bunches were scattered one about every 3 square feet, but a couple of acres were covered uniformly by dense, large old bunches, gray leaf litter built up, and here the density was about one bunch per square foot. Standing in the grassland of pure needlegrass was like being back in time, the culms reaching thigh-high, and so dense as to mostly obscure the bunches beneath them. The wind blew the stems, making a loud rustling noise. A few California ground squirrel (Spermophilus beecheyi) and Audubon cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii) trails ran through the bunches. Fiddleneck (Amsicnkia sp.), Popcorn flower (Plagiobothrys sp.), and Chia grew in the more open needlegrass fields. Western bluebirds (Sialia mexicana) softly churped in the Blue oaks nearby.

Purple needlegrass grows with Blue wildrye on the top peak of Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County. I found it also in the tule elk fenced Tomales Point area.

In southern California, I came across Purple needlegrass commonly in open areas in Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (Ventura/Los Angeles Counties) growing with scattered Prickly pear (Opuntia sp.), California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), Whipple yucca (Yucca whipllei), Black sage (Salvia mellifera), and Small-flowered oniongrass.

I imagine the life cycle of this noble bunchgrass repeating itself through layers of time in Old California. Purple needlegrass produced new green leaves with the first quarter inch of rain in the fall after the long dry summer. Within four days of rain in October, a flush of green tinted the tan-colored hills. Leaf growth was slowest during the cold of December and January, but picked up in February with warming weather. By early spring it began vegetative tillering to expand the bunch outward to grow larger. Maximun growth took place in April and May (Sampson and McCarty 1930). Leaves were usually 3 mm wide or less, flat or rolled (involute). Flowering culms appeared in early April. The spikelets opened to reveal the flowers for pollination in May — it was sensitive to grazing during this time. The seeds set in May and early June, then fell from the stems or were caught on the fur of passing animals to be dispersed. Growth may have stopped by as late as mid July. It needed enough good top growth in spring to store carbohydrate food reserves in its stem bases and roots to survive the five-month summer dry period. The roots extended down three feet underground, densest in the upper six inches of soil (Hull and Muller 1977).

During the summer the bunches were quiescent. Soil moisture levels in these perennial grasslands today are often much greater than in introduced annual grasslands, as the perennials do not suck up surface soil water as much as the shallow-rooted annual grasses. Oak savannas may be significantly affected by this as annual grasses compete with oak seedlings for soil moisture, leading potentially to oak declines.

Centuries ago, a man or woman with long experience might have walked through the dry tufts of grass in a local valley and lit a late summer fire which lightly crackled through the dried dead leaves and stems from the previous growing season. This stimulated new stem and seed production, regenerating the population. A large herd of tule elk lightly grazing through in early summer might have prolonged the green growth of the needlegrasses, but also delayed the start of growth in the following rainy season as the bunches used much of their stem base and root food reserves to put out new leaves. After clipping by grazing animals or burning by fire the needlegrasses potentially produced new blades within two days.

The strong awn of the seed of needlegrasses had several functions to help it disperse and get planted: it acted as a hairy “sticky” hook to catch on the fur of passing elk legs or jackrabbits (or my socks!). When the seed fell to the ground, the rains wet the awn and caused it to straighten out; when dry it bent back. This process continued until the floret drilled itself into a crack or loose spot on the ground — perhaps a rodent burrow digging. The stiff unidirectional hairs on the seed body and awn (described as a “scabrous” condition) also helped to work the seed into the fur of an animal or into the ground. My sister’s yard showed this specialty quite clearly as needlegrass seeds happily bored into all the dirt crevices between her brick patio, producing a pure stand free of competition.

Seeds were capable of germinating 3 weeks after a good rain, but today may be killed by competiton with rapidly growing annual grass seedlings; high levels of mulch also suppressed germination, and thus fire or light disturbance may actually have aided the seeds in getting established (Bartolome and Gemmill 1981, D’Antonio et al. 2003).

Cattle relish needlegrass, and on heavily grazed ranges the bunches thin out and become quite small compared to ungrazed ranges — down to one inch in basal diameter I noticed. In extreme cases I have seen bunches barely detectable with only a few basal blades and a lone culm to give away their presence. But the fenced livestock ranges are quite different from the former fenceless elk habitats where herds roamed widely and freely, impacting any one stand of needlegrass little. Today’s high stocking rates and long-term grazing seasons by cattle and sheep have eliminated needlegrasses completely over vast areas of California grasslands.

Tule elk apparently do not eliminate Purple needlegrass, as I found it common and flowering within the fenced off Tomales Point Tule Elk Reserve on Point Reyes National Seashore. It has been eliminated on the adjacent dairy and beef operations in the Pastoral Zone.

Recently a few botanists and restorationists suggested Purple needlegrass was never dominant, and that some areas had no cover of perennial grass: there are theories of a coastal annual wildflower community on the Los Angeles plain, and discussion of tarweed-lupine dominance in central California. Supporters appear to be trying to “shift the paradigm” about bunchgrass dominance towards other open plant communities. Glen Holstein (2001), for instance, argued against the “bunchgrass paradigm” of dominant Stipa pulchra grasslands in the Sacramento Valley and instead saw pre-agricultural communties of Creeping wildrye (Elymus triticoides) or tarweeds. I agree that Elymus triticoides must have formed luxuriant communities along the rivers and in flatland oak savannas. But I disagree that the bunchgrasses were insignificant, as I have found Stipa pulchra on well-drained areas of the valley, probably once forming a complex patch mosaic with Creeping wildrye which probably grew in pure stands in moist soils and floodplains of the rivers. In fact, I have found Purple needlegrass often across the state on valley flats where the lack of development has left it a foothold. Holstein theorized that eastern Sacramento Valley old loam terraces, where vernal pools were common, had a special tarweed community dominated by Hemizonia species and Holocarpha virgata and no bunchgrasses; again, I have seen in these same areas relicts of native bluegrass, Nodding needlegrass, and Three-awn (Aristida hamulosa). Negative evidence does not make good evidence for reconsturcting early California grasslands I discovered.

As part of the “paradigm shift” attempt, attacks on the work of early ecologist Frederick Clements have been launched. Clements developed a method he called “relict analysis” in California to find evidence of former native grasses along less disturbed sites such as railroad right-of-ways, roadsides, “fenced-out” areas, and rocky slopes with reduced competition. He thought these could indicate lost habitats when backed up by diverse evidence such as old botanical surveys and historical accounts. At Banning in Riverside County, for instance, he found relict Purple needlegrass hanging on in an overgrazed pasture protected by growing within a prickly pear cactus patch (Opuntia sp.) (Clements 1934). Because some of Clements’ theories on ecology such as the “climax” are falling into disfavor, a few contemporary researchers (such as Hamilton 1997) have questioned all his methods, and debate whether these stands are actually relict, or rather invasive themselves. But Clements began his searches early enough that he witnessed changes that we a century later have all but collectively forgotten:

“The search for bunch-grass relicts in 1917-18 was first directed to [railroad] trackways, not merely because such relicts were often remarkable in purity and extent, but also because they were rapidly being destroyed as a war-time measure to produce a great crop of wheat. Many hundred miles of a nearly continuous consociation of Stipa pulchra were obliterated in the Great Valley, leaving sparse fragments where plough and fire had taken lighter toll…. It was especial good fortune to record these extensive relicts and then to have them reduced to patches here and there, as it not only confirms the other evidence to the effect grassland was the original great climax of California, but it throws needed light upon other regions known only by the mosaic of relicts” (Clements 1934: 56).

Clements showed a photograph of large Purple needlegrass bunches growing along a railway in the San Joaquin Valley near Fresno, and I have explored these same areas along the railroad edges and found similar relicts of beautiful stands of Stipa pulchra inside the fences that lined the tracks. Outside the fences I saw well-tended raisin-grape vinyards, wheat fields, houses, and weedy pastures with cattle, goats and sheep grazing so heavily that not much remained. Much of the moister eastern edge of the San Joaquin Valley primordially might have been covered by such bunchgrasses. Similar relict methods are used today by historical ecologists in the Mediterranean region to reconstruct old layers of vegetation (Grove and Racham 2001).

Other positive evidence comes from opal phytolith analysis. Grass ecologist James Bartolome and his colleagues found a greater frequency of panicoid-type phytoliths, which match Stipa pulchra types, several inches below the soil surface in what are presently introduced annual grasslands. They suggested this indicates a prior higher density of Purple needlegrass in places where today only isolated bunches remain (Bartolome, Klukkert and Barry 1986).

To call Purple needlegrass merely a weedy colonizer of disturbed sites is inaccurate I think. Instead of a changing paradigm that claims needlegrass was never common in some sort of stable native prairie, we might think of California’s past grasslands as inherently disturbance-oriented ecosystems. “Highly variable nonequilibrium systems,” say ecologists (Jackson and Bartolome 2007), whole communities adapted to regular disturbances of drought and El Nino, fire and Indian seed gathering, elk grazing and rodent burrowing. Purple needlegrass may have been dominant in many areas because it was so well evolved to this kind of unstable regime.

I collected needlegrass seeds in 1995 and gave a bag of them to my sister Margot, who then planted them in a narrow strip along her walkway. They took off and then spread to the adjacent brick patio, and later to bare dirt in the parking strip by the street after removal of non-native bushes. This grass became so successful here that Margot occasionally had to weed them back to make room for the junegrasses and red fescues she had planted. Wildlfowers seemed to thrive in their company.

Feathergrass

I have heard Nodding needlegrass (Stipa cernua, formerly Nassella c.) called “Feathergrass,” a fitting name as it is one of the most beautiful of our grasses. It is a tall sturdy bunch yet with graceful delicate flower panicles tinged with purple. The long awns curve sinuously in May and June. On a windy day a field of Feathergrass waves like fine hair or the mane of a blonde horse, glinting in the sunlight quietly. The blades are narrower than Purple needlegrass (usually 1.5 mm wide), and are often glaucous (light green tinged with bluish-white) in color. It never gets lush like S. pulchra, but is very drought tolerant.

In samples of where this bunch grows, I found Feathergrass with One-sided bluegrass, Small-flowered melic (Melica imperfecta) and California melic, and Big squirreltail along Mines Road in Alameda County in the arid inland Coast Ranges in a grassland mosaic with Blue oak, Gray pine (Pinus sabiniana), and chaparral.

At the Rush Ranch Open Space in the Montezuma Hills of Solano County I saw how Nodding needlegrass survived cattle grazing on these arid barren grasslands, coming down to the edges of the tule marshes of Suisun Bay. The bunches interfingered with Creeping wildrye and Saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) at the marsh ecotone. In one section fenced off from cattle, the Nodding needlegrass was dense and abundant on the gentle slopes — this grass must have originally covered the hills and plains away from the marshes, I thought.

In the Sierra foothills I found relicts in Blue oak savanna at Millerton Lake State Recreation Area (Madera/Fresno Counties) growing with One-sided bluegrass, California melic, Soap plant (Chorogalum pomeridianum), Doveweed (Eremocarpus setigerus), yarrow, and phacelia.

One year the rains fell just right to produce large patches of waving straw-purple panicles of needlegrass above the introduced annuals along Tehachapi Pass roads (Kern County) in May — each awn glinted in the setting sun like threads of white gold. The next year a wet spring made the introduced wild oats (Avena spp.) and ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus) grow tall, and I could barely detect the bunchgrasses.

I found Feathergrasses common scattered on a mowed divider of Highway 65 just north of Porterville (Tulare County) on the east edge of the San Joaquin Valley, a few great Valley oaks towering nearby, and orange groves and alfalfa fields taking up most of the surroundings.

At Carrizo Plain National Monument (San Luis Obispo County) Nodding needlegrasses were recovering from historic agriculture and drought, and grew densely on hill slopes too steep to plough; elsewhere they dotted rolling flats and Saltbush barrens (Atriplex polycarpa), often along fenced-out roadsides and parking lot edges away from cattle overgrazing. They were regaining a foothold on gentle slopes, bajadas, and clay flats.

Driving over the Cajon Pass freeway toward San Bernardino I spotted a wash with native vegetation remaining, so I pulled off to investigate. Among the open Bush buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), Scale broom (Lepidospartum squamatum), Croton (Croton californicus), White sage (Salvia apiana), and Yerba Santa (Eriodictyon trichocalyx) were a few waving seedheads from a bunch of Nodding needlegrass, probably a relict from a once vast bunchgrassland across the San Bernardino plains in former times. Prickly pear (Opuntia X vaseyi) and the strange long thin crawling arms of Cane cholla (O. parryi) grew scattered on the stony dry washbed. Pioneering southern California botanists called Nodding needlegrass more common in the drier interior, while Purple needlegrass was widespread coastally on good soils (Davidson and Moxley 1923).

In June 2004 I drove from El Cajon to Ramona, inspecting hills once covered with chaparral, now burned off by devastating wildfires. But I noticed long Nodding needlegrass stems waving in the breezes on the burnt hills, ready to regrow into a grassland.

One of the best places to see acres of Nodding needlegrass is at Basalt Camp in San Luis Resevoir State Recreation Area in the inner Coast Range of Merced County: on a visit in February 1987 I found abundant large and small patches on valley flats, low hills, higher slopes, and dry gullies, the blades greened up but the culms old and gray from last season. The grasses covered all slopes regardless of aspect. The bunches were largest on valley floors, smaller on slopes and rocky areas, and smallest on cattle grazed areas. I watched a California jackrabbit graze the edges of several bunches. Some One-sided bluegrass, California melic, and Prairie junegrass grew scattered in the grassland, and native annual foxtail grass occurred on a bare sandstone outcrop. In June I returned and found wildflowers in the needlegrass prairie: tarweed (Holocarpha virgata), Doveweed, milkweed (Asclepias sp.), milkvetch (Astragalus sp.), a pink-flowered buckwheat (Eriogonum sp.), a yellow-flowered gum plant (Grindelia sp.), and Vinegar weed (Trichostema lanceolatum) with deep blue flowers.

A vanished community reconstructed from anecdotal history, photographs, voucher specimens, and biological field notes, was the “Los Angeles coastal prairie” according to botanists Rudi Mattoni and Travis Longcore (1997). Covering extensive dune sand deposited along the coast by the Los Angeles River, this wildflower-rich habitat mixed with California sagebrush on sandstone outcrops, wetlands, and vernal pools. Rolling plains and mesas toward the sea greeted travelers with showy poppies (Eschscholzia californica), Dove lupines (Lupinus bicolor), verbenas (Verbena bracteata), phacelias (Phacelia stellaris), lotus (Lotus strigosus), Dwarf plantain (Plantago erecta), California sun cup (Camissonia bistorta), Purple owl’s clover (Castilleja exserta), and Tidy-tips (Layia platyglossa). Specimens of native grasses collected before 1940 indicated a typical California grassland with Nodding needlegrass, Prairie Junegrass, Creeping wildrye in low areas, Saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), and the native annual Foxtail grass (Vulpia microstachys). San Diego coast horned lizards were said to be the most common reptile in this prairie. The vernal pools contained fairy shrimp (Streptocephalus and Branchinecta) when wet, as well as the tadpoles of breeding Spadefoot toads (Scaphiopus hammondii). The vernal pool endemic grass Orcuttia californica was recorded. Attempts are being made to restore this interesting community.

As for edibility, Kern County botanist-rancher E. C. Twisselman (1967) called Nodding needlegrass of secondary importance for livestock, as the bunches were often full of dry material. Therefore the grasses may survive on rangelands with rainfall above 8 inches a year.

Little Tufts with Wildflowers

“There were wildflowers, acres of them, of every imaginable color and hue — the air redolent with their perfume — growing in such denseness as to fairly enmesh one’s feet. One could walk for hours continually discovering new varieties.”

–L. J. Rose of Sunnyslope in Riverside County (Rose 1959)

One-sided bluegrass (Poa secunda, formerly P. scabrella and P. tenerrima), also known as Sandberg bluegrass, is a small tufted bunchgrass that probably grew abundantly in between the needlegrasses and in pure stands. Not really blue, in the wet season I have seen groups of these little green tufts form fields of foot-high waving seedheads among thousands of orange California poppies (go to the Antelope Valley California Poppy State Reserve in the transitional desert grassland of northeastern Los Angeles County). Bluegrasses allowed the wildflower displays full reign to bloom as there was plenty of bare ground between the grasses. Today these spaces are usually filled with introduced annual grasses. Sometimes the culms grow no taller than a foot, in moister spots to 2 feet. This bunchgrass is an obligate dormant plant by the June dry season, turning from green to dry-tan and yellow ochre.

Also called Malpais bluegrass, Steppe bluegrass, or Pine bluegrass, this is a very widespread species in the western United States, common in the Great Basin, Mojave Desert, and into the sagebrush steppes of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Sereno Watson, in his Botany of California (1880) called it frequent throughout the state from San Diego to Oregon, a “most valuable bunchgrass.” He said the Indians collected its purplish grain for food. I have seen bluegrasses put out their slender seedheads earlier than most other native grasses, in March — a good early food plant perhaps. Later botanists noted it common across the open dry hills of the inner South Coast Range (Sharsmith 1936).

In the Palouse Prairie of eastern Washington I found these bluegrasses growing with the bunchgrass Needle-and-thread (Stipa comata), a species reminescent of the Stipas that replace it in the California Floristic Region. Here, even though the climate differed from that of western California, the grassland observer can gain a clue as to the pristine habit of a “Poa-Stipa” association free of the hordes of introduced annuals. The little Poa secunda tufts mixed evenly with the larger needlegrass bunches over hills and flats.

In California I often found bluegrasses restricted to cooler north-facing slopes, while needlegrasses grew on the hotter south-facing sides (Tilden-Wildcat Canyon Regional Park in Contra Costa County, Tehachapi Pass in Kern County). But in other areas the two mixed freely on flats and hills regardless of aspect. Inland from the bay on Mount Diablo (Contra Costa County) bluegrass grew commonly on north- or south-facing slopes, and on thin soils on the valley floor; I also found it colonizing gopher mounds. At Donner Canyon in the same park I saw tufts of bluegrass on a flat growing with abundant wildflowers in April 1988: Blow wives (Achyrachaena mollis), Grass nut (Triteleia laxa), Ookow (Dichelostemma congestum), Purple owls clover (Castilleja exserta), California poppy, fiddleneck (Amsinckia sp.), California buttercups (Ranunculus californicus), white yarrow, and dove lupine. In Pine Canyon on one hike in June 1985, I noticed little scattered bluegrass tufts to be the most common native grass on Blue oak-wooded slopes.

On Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County I found this bluegrass in ridgetop grasslands with Purple needlegrass, Idaho fescue, Red fescue, California oatgrass, Mountain brome, and Blue wildrye. I have found it in coastal prairie at South Beach in Point Reyes National Seashore, as well as within the elk-grazed Tomales Point fenced area.

In very arid areas such as the saltbush flats of the western San Joaquin Valley I have seen bluegrass in Kern County oil fields on the edges of the hills. In the North Coast Range I found bluegrasses growing on rockier or thinner soils, while Purple needlegrass and California oatgrass dominated the heavier, deeper soils. At Vina Plains on the east side of the Sacramento Valley south of Red Bluff (Tehama County) in April, I found scattered small purplish tufts of bluegrass fairly commonly on the flats in and around dry vernal pools; wildflowers such as Goldfields (Lasthenia sp.) grew abundantly around them.

What the community was like before the weedy invasions cannot now be known with certainty, but I suspect that much Poa has been eliminated by livestock grazing, especially by sheep who find its small tender tufts particularly palatable. In unfenced elk and bison ranges it can take relatively heavy grazing by these native ungulates. Aboriginally bluegrass was probably widespread in open well-drained valley grasslands of many topographic types, interior to the coastal prairie, as well as in Blue oak savannas and woodlands, up into the pine belts, and out into the deserts.

Oniongrasses

California melic, or Oniongrass (Melica californica) is an important tufted grass endemic to California and Malheur County, Oregon, found from Ventura County north throughout the Coast Ranges, Central Valley, and Sierra Foothills (Hitchcock 1950, Crampton 1974, Munz and Keck 1959). You can pull out a stem and find a small onion-like bulge at the base of the grasses in this group.

In the East Bay this beautiful plant was common on hills and open slopes during my explorations. I found it often scattered among Purple needlegrass prairies on slopes and valley floors, and in the arid interior Coast Ranges it often grew under Blue oaks and Valley oaks. Around Rock City on Mount Diablo State Park, for example, I found this grass abundant on open hills and flats, with nearby groves of live oak, Gray pine, and Buckeye; large bunches grew along the Summit Trail.

In Tilden Regional Park I have seen California melics growing scattered among Purple needlegrass, but also in fairly dense patches that excluded all wildflowers but tall yarrows. When the patches started to dry out in late May the spikes with their papery glumes turned silvery white, contrasting with the yellowing panicles of the needlegrasses, and pastel light-brown panicles of Mountain brome. The spikelets are large, 7 to 10 mm long.

Even in grazed ranges I can often manage to find California melic “hiding” next to boulders or on steep slopes where the cows cannot reach. It is eliminated by livestock grazing on fenced pastures. Along Mines Road in eastern Alameda County, it holds its own: in April 1997 I saw many large green bunches growing on open slopes with Purple needlegrass and One-sided bluegrass, the spaces filled with showy California poppies, Purple owl’s clover, and Chick lupine (Lupinus microcarpus). I have watched Mule deer nip off the seedheads in spring.

On San Bruno Mountain on the San Francisco peninsula, I found California melic in a coastal prairie with Idaho fescue. Bunchgrasses that may be this species can be found within the Tomales Point Tule Elk Reserve in Point Reyes National Seashore.

Small-flowered melic (Melica imperfecta) is a common arid-adapted bunchgrass found from central California south to Baja. Its blades are relatively wide, and as early as March on warm slopes the bunches become full of narrow but often branching panicles with dense, shiny, purplish spikelets. By May the seeds begin to dry and turn brownish. The spikelets are half the size of those of California melic.

In foggy Tilden Regional Park in the East Bay hills, I found this dry-adapted bunchgrass keeping to the poorer soils of chert, basalt, and shale and not on the more mesic substrates of sandstone-based clays and loams dominated by the other natives. It grew in the open and under the canopies of Blue oaks — I saw it to be quite common under Blue oaks at Pine Canyon in Mount Diablo State Park.

It mixes into coastal prairie from chaparral edges on Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, and increases on chaparral burns.

Melica imperfecta may have been one of the most common native grasses in southern coastal California (Abrams 1917), but as it was favored as forage by all classes of livestock it probably suffered severe overgrazing and reduction. Watson reported it at San Diego, San Bernardino, and at the La Purisima Mission in the Santa Ynez River Valley of Santa Barbara County; at Los Angeles it was described as having pale straw-colored florets. Thus it may have been a coastal grass along the southern California beaches and bluffs.

At Ronald W. Caspers Regional Park in Orange County I found lush large fields of Small-flowered melic taking over recently burned coastal sage scrub hills — acres of panicles waving in the sea breezes. On a nearby grassy ridgetop the melic grew with abundant Purple needlegrass, a few Giant needlegrass (Stipa coronata), and some Bearded canegrass (Bothriochloa barbinodis). This might have been a clue to the original vegetative cover of the place. I have found remnant plants elsewhere on the edges of the town of Rancho Palos Verdes (Los Angeles County) growing with Purple needlegrass and California sagebrush, as well as in Griffith Park, Santa Monica Mountains just north of Los Angeles itself — relicts hanging on to scraps of open space.

I have watched cattle pick out green bunches of Small-flowered melic in winter, apparently preferring them to exotic annual grass. Oniongrasses will not stand heavy grazing, and have been eliminated from many over-used ranges.

Tumblegrass

Field sketch of Elymus elymoides in interior California.

Big squirreltail grass (Elymus multisetus, formerly Sitanion jubatum) is common in dry open grasslands often on xeric gravelly, sandy sites. I find it on the more xeric soils in the coastal fog belt hills and valleys, such as serpentine soils and volcanic areas.

This bunchgrass can add textural variety to a grassland with its unique wide spikes that appear like a head of green-blonde hair when moist in spring and the long awns still together like miniature horse’s tails; in summer the awns dry and open up into “bottlebrushes,” with a fine light bronze or silver sheen in the hot sun. When ripe the rachis (seedhead stem) breaks off and with long awns spread out laterally the seedheads roll about in the wind, an apparent adaptation to seed dispersal on open bunchgrasslands where bare soil would have been common before the mass invasion of dense European annual grasses that now clog even xeric grasslands. This gives us a clue that on drier sites the native grasslands were often noncontinuous in cover, allowing Coast horned lizards, Heerman’s kangaroo rats, pocket mice, and other small animals to move about freely. It should be used more in restoration projects.

These low bunches are common in Big Springs Canyon, Tilden Regional Park (Contra Costa County), in the coastal fog belt on basaltic soils. There I noticed they seemed to compete poorly on dry slopes where exotic annual grass was dense and tall, but they did well growing among tall Purple needlegrass bunches, even touching them. Their blades can be green or glaucous (bluish-white tinged). At Morgan Territory Preserve in the eastern part of the county I found bunches still green in June, growing with Purple needlegrass in the open and under the Blue oaks with Blue wildrye. In places they were common scattered mixing with groups of Prairie junegrasses. Others grew on a Valley oak flat.

At Los Trancos Open Space Preserve, San Mateo County, I found this species common on some slopes covering large areas in pure stands. Along the American River in Ancil Hoffman Park, Sacramento, I found Big squirreltail bunches on dry cobbly and gravelly floodplains.

The shorter-awned species called simply Squirreltail (Elymus elymoides, formerly Sitanion hystrix) I have found in higher-elevation Coast Ranges, foothills, and mountains. At Burma Ridge on Mount Diablo State Park, for example, I saw Squirreltail abundant on arid rocky grasslands with Sandberg bluegrass, Prairie junegrass, Small-flowered melic, native Vulpia, and buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum). I also found some on a serpentine outcrop in the Ohlone Wilderness (Alameda County), and on basalt barrens in the Sierra Foothills. I found Squirreltail bunches abundant on the arid edges of the Mojave Desert, covering 20 to 30% of the ground in the Tehachapi Mountains, as along Highway 58 (Kern County). Elymus elymoides is common across the sagebrush steppe of Nevada, Idaho, and beyond, where livestock grazing has not eliminated it.

Showing how actively grasses are still evolving, changing, and adapting to California climates and geology, squirreltail grasses often hybridize with each other and with Blue wildrye. One hybrid I see in costal foggy Tilden-Wildcat Canyon is Hansen squirreltail (once thought to be a seperate species, “Elymus hanseni”), an unusually large bunch growing singly or in small groups with tall spikes and seedsheads combining the characters of both its parents — the spikes only partly break off.

Native Annual Grasses

The original California grasslands may have had more native annual grasses than is supposed, little plants easily overlooked today and probably largely crowded out by exotic grasses.

Small foxtail (Vulpia microstachys, formerly placed in the genus Festuca) was probably one of the most common annual grasses in California, although I do not think it was ever as abundant as exotic annual grasses are today. It is often now relict on poor stony or sandy soils, burns, trailsides or other disturbed areas where competition is at a minimum. In pristine times I believe it was able to grow in better soils in many areas between the bunchgrasses, sharing the open spaces with wildflowers. I have seen plants from 6 to 18 inches in height.

In my explorations I found the little Vulpias most common in the drier interior from the oak belt to the lowest valley floors. It was one of the few native grasses that survived in the desert-like bottom of the San Joaquin Valley. A record of its past numbers was recorded by Watson (1880) who said it was very frequent the whole length of the state, and was abundant on dry hills. Other botanists found native foxtail common across the Mount Hamilton Range on open hills (Sharsmith 1936). Twisselman (1967) in Kern County called it “often abundant” in the San Joaquin Valley up into the Blue oak zone. It was similarly found in open gravelly areas and foothills across southern California (Abrams 1917).

At Skyline Regional Park in Napa County I found Vulpia microstachys common in places between Purple needlegrass bunches in a Blue oak savanna. At Lake Berryessa these tiny foxtail grasses were abundant in June of 1989 in the open and under Blue oaks in the picnic areas on the rolling flats of the valley. This is one of the few places where I have found this species common on flats, and not confined to relict places on cliffs or rocky sites due to competition with introduced annual grasses that normally fill the ground. The picnic area here is regulaly mowed and this may be why the exotic grasses do not thrive — introduced wild oats and Soft chess (Bromus mollis) were uncommon. In addition, the bare ground of the receding resevoir shoreline gave competition-free habitat for these natives. Where bare ground is widespread and leaf litter is minimal, Vulpia thrives. In nearby Purple needlegrass stands where the bunches grew densely (about one per square foot), and old gray leaf litter built up, the Vulpias were also excluded.

I also found these low grasses growing along old disturbed trails on Shell Ridge Regional Park in the foothills of Mount Diablo (Contra Costa County), where competition from the introduced annuals was less. One-sided bluegrass, Purple needlegrass, and Prairie junegrass grew with it. In Pine Canyon 3-foot tall Vulpia stems grew on disturbed sunny roadsides. At Morgan Territory Regional Preserve (Contra Costa County) in April 1989 I was delighted to find abundant native annual foxtail growing in the open and under Blue oaks, on all exposures, densely with Goldfields and by themselves. They were small and green and did not block the flowers; variable in character, some were pubescent (hairy), others scabrous. Native Vulpias were also still common mixing in grasslands and Blue oak woods at Black Diamond Mine Regional Park in Contra Costa County. I saw them growing on chert exposures around Coast live oak and Coulter pine (Pinus coulteri). On new chaparral burns on Cuesta Ridge in San Luis Obispo County these unassuming annuals soaked up the sun.

The variety of habitats that this grass once inhabited was indicated to me when I found them in dry hogwallows between mima mounds on open basaltic terrace grassland on the upper Sacramento Valley floor near Rocklin (Placer County). At Vina Plains (Tehama County) Vulpia microstachys was abundant, but not in the vernal pools; instead it grew around them, forming a matrix for wildflowers such as Goldfields, Meadow foam (Limnanthes sp.), Yellow mariposa lilies (Calochortus luteus), Tidy tips (Layia platyglossa), and Blue dicks (Dichelostemma pulchellum). At Byron in the desert-like alkaline flats of the San Joaquin Valley (eastern Contra Costa County) I found in April 1985 a small patch of this grass on a flat by an alkali scald, with Parish brittlescale (Atriplex parishii) and Iodione bush (Allenrolfea occidentalis).

On terra Linda Ridge in Marin County, I found these small Vulpias growing among Pruple needlegrass, Prairie junegrass, Sandberg bluegrass, California melic, and Big squirreltain on serpentine slopes.

Vulpia microstachys has a very wide range of variation in characters, and I think it is undergoing active evolutionary diversification, even though it has been recently overwhelmed by the flood of invasive non-native Mediterranean annual grasses that often out-compete it.

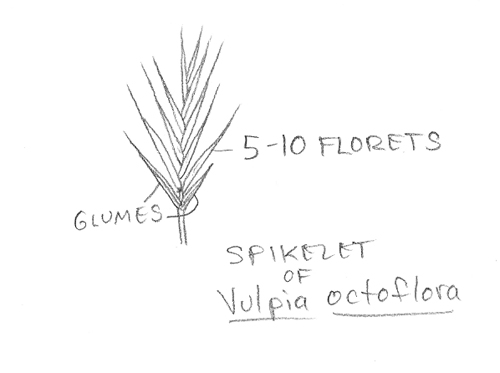

Six-weeks foxtail or Six-weeks fescue (V. octoflora) is an annual similar to V. microstachys on dry open places throughout the state and much of North America (Munz and Keck 1959). It occurrs on gravelly soil, but I also found it hiding on sandstone banks along a hill-slope trail, and occupying bare dirt areas created by gophers in an otherwise dense grassland in Wildcat Canyon Regional Park (Contra Costa County), surrounding by European wild oats and soft chess stands on the better soils. On grassland burns I saw it spreading out in large numbers. Watson (1880) reported V. octoflora (under Festuca tenella) as abundant on dry hills near San Francisco, in the Napa Valley, and to Oregon. Hiking Garin-Dry Creek Pioneer Regional Park in Alameda County in July of 1997, I came upon this little grass abundantly on the sandstone hills and ridges, sometimes mixing with Rancheria clover (Trifolium albopurpureum) and tarweeds (Hemizonia spp.), as well as bunches of Nodding needlegrass which were spaced 6 inches apart. The Vulpias here were dry and tangled at this time of year, 6 inches high or less on windy ridgetops.