“By dispensing plants and animals all around the world, humans have shaped global cuisines and agricultural practices. One of the most fascinating and least-discussed episodes in this process took place along the Silk Road.” — Fruit from the Sands by Robert N. Spengler III

———————

My understanding of the origins of agriculture and the early years of crop domestication are cursory at best. The education I received was mostly concerned with the Fertile Crescent, as well as crops domesticated by early Americans. The Silk Road, as I understood it, was the route or routes used to move goods across Asia and into eastern Europe well after the domestication of many of the crops we know today. Other than the fact that several important crops originate there, little was ever taught to me about Central Asia and its deep connection to agriculture and crop domestication. I suppose that’s why when I picked up Fruit from the Sands by Robert N. Spengler III, published last year by University of California Press, I wasn’t entirely prepared for what I was about to read.

It wasn’t until I read a few academic reviews of Fruit from the Sands that I really started to understand. Spengler’s book is groundbreaking, and much of the research he presents is relatively new. The people of Central Asia played a monumental role in discovering and developing much of the food we grow today and some of the techniques we use to grow them, and a more complete story is finally coming to light thanks to the work of archaeologists like Spengler, as well as advances in technology that help us make sense of their findings.

This long history with agricultural development can still be seen today in the markets of Central Asia, which are loaded with countless varieties of fruits, grains, and nuts, many of which are unique to the area. Yet this abundance is also at risk. Crop varieties are being lost at an alarming rate with the expansion of industrial agriculture and the reliance on a small selection of cultivars. With that comes the loss of local agricultural knowledge. Yet, with climate change looming, diversity in agriculture is increasingly important and one of the tools necessary for maintaining an abundant and reliable food supply. Unveiling a thorough history of our species’ agricultural roots will not only give us an understanding as to how we got here, but will also help us learn from past successes and failures. Hence, the work that Spengler and others in the field of archaeobotany are doing is crucial.

To set the stage for a discussion of “the Silk Road origins of the foods we eat,” Spengler offers his definition of the Silk Road. The term is misleading because there isn’t (and never was) a single road, and the goods, which were transported in all directions across Asia, included much more than silk. In fact, some of what was transported wasn’t a good at all, but knowledge, culture, and religion. In Spengler’s words, “The Silk Road … is better thought of as a dynamic cultural phenomenon, marked by increased mobility and interconnectivity in Eurasia, which linked far-flung cultures….This network of exchange, which placed Central Asia at the center of the ancient world, looked more like the spokes of a wheel than a straight road.” Spengler also sees the origins of the Silk Road going back at least five thousand years, much earlier than many might expect.

Most of Spengler’s book is organized into chapters discussing a single crop or group of crops, beginning with grains (millet, rice, barley, wheat) then moving on to fruits, nuts, and vegetables before ending with spices, oils, and teas. Each chapter compiles massive amounts of research that can be a bit overwhelming to take in all at once. Luckily each section includes a short summary, which nicely distills the information down into something more digestible.

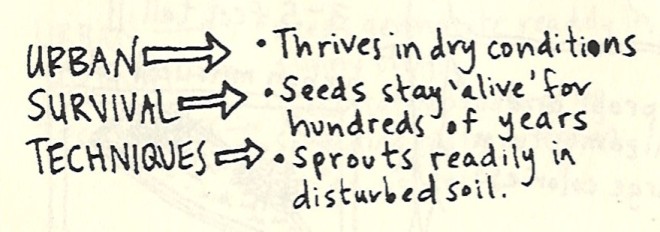

Spengler’s chapter on broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) is particularly powerful. While in today’s world millet has largely “been reduced to a children’s breakfast food in Russia and bird food in Western Europe and America,” it was “arguably the most influential crop of the ancient world.” Originally domesticated in East Asia, “it passed along the mountain foothills of Central Asia and into Europe by the second millennium BC.” It is a high-yielding crop adapted to hot, dry conditions that, with the development of summer irrigation, could be grown year-round. These and other appealing qualities have led to an increase in the popularity of millet, so much so that 2023 will be the International Year of Millets.

The “poster child” for Spengler’s book may very well be the apple. Popular the world over, the modern apple began its journey in Central Asia. As Spengler writes, “the true ancestor of the modern apple is Malus sieversii,” and “remnant populations of wild apple trees survive in southeastern Kazakhstan today.” As the trees were brought westward, they hybridized with other wild apple species, bringing rise to the incredible diversity of apple cultivars we know today. Sadly though, most of us are only familiar with the small handful of common varieties found at our local supermarkets.

Of course, as Spengler says, “No discussion of plants on the Silk Road would be complete without the inclusion of tea (Camellia sinensis),” a topic that could produce volumes on its own. Despite the brevity of the section on tea, Spengler has some interesting things to say. One in particular involves the transport of tea to Tibet in the seventh century, where “an unquenchable thirst for tea” had developed. But the journey there was long and difficult. Fermented and oxidized tea leaves traveled best. Along the way, “the leaves were exposed to extreme cold as well as hot and humid temperatures in the lowlands, and all the time they were jostled on the backs of sweaty horses and mules.” This, however, only improved the tea, as teas exposed to such conditions “became a highly sought-after commodity among the elites.”

“In Central Asia, Mongolia, and Tibet, tea leaves were oxidized, dried, and compressed into hard bricks from which chunks could be broken off and immersed in water.” – Robert N. Spengler III in Fruit from the Sands (photo via wikimedia commons)

As dense as this book is, it’s also quite approachable. The information presented in each of the chapters is thorough enough to be textbook material, but Spengler does such a nice job summing up the main points, that there are plenty of great takeaways for the casual reader. For those wanting a deeper dive into the history of our food (which in many ways is the history of us), Spengler’s book is an excellent starting point.

More Reviews of Fruit from the Sands:

———————

Our Instagram has been revived!!! After nearly a year of silence, we are posting again. Follow us @awkwardbotany.