Who first said 'The pen is mightier than the sword'?

- Published

Tribute cartoons to the journalists at Charlie Hebdo compare pencils with guns, writers with fighters - it's also why some demonstrators are holding pens and pencils in the air. Many of the cartoons assert that "the pen is mightier than the sword". But where does this idea originate?

The English words "The pen is mightier than the sword" were first written by novelist and playwright Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1839, in his historical play Cardinal Richelieu.

Richelieu, chief minister to King Louis XIII, discovers a plot to kill him, but as a priest he is unable to take up arms against his enemies.

His page, Francois, points out: But now, at your command are other weapons, my good Lord.

Richelieu agrees: The pen is mightier than the sword... Take away the sword; States can be saved without it!

The saying quickly gained currency, says Susan Ratcliffe, associate editor of the Oxford Quotations Dictionaries. "By the 1840s it was a commonplace."

Today it is used in many languages, mostly translated from the English. The French version is: "La plume est plus forte que l'epee."

Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Bulwer-Lytton is also renowned for the opening line "It was a dark and stormy night" and has given his name to an annual contest for badly written first sentences.

This is the first sentence of his 1830 novel, Paul Clifford, in full:

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents - except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

In addition, Bulwer-Lytton is credited with popularising the term "the great unwashed" which he used in the same novel.

According to the Cambridge Dictionaries website the saying emphasises that "thinking and writing have more influence on people and events than the use of force or violence".

But Bulwer-Lytton was not necessarily the first to express this thought. Ratcliffe points to two earlier texts.

Robert Burton, in The Anatomy of Melancholy, published in the early 17th Century, describes how bitter jests and satire can cause distress - and he suggests that "A blow with a word strikes deeper than a blow with a sword" was already, even in his day, an "old saying".

A similar phrase appears in George Whetstone's Heptameron of Civil Discourses, published in 1582, Ratcliffe notes. "The dashe of a Pen, is more greeuous then the counterbuse of a Launce." (The dash of a pen is more grievous than the counter use of a lance.)

Going back further, the Greek poet Euripides, who died about 406 BC, is sometimes quoted as writing: "The tongue is mightier than the blade." But classics professor Armand D'Angour of Oxford University is doubtful about this.

"Occurrences of 'tongue' in Euripides are generally negative - the tongue (i.e. speech) is less reliable than deeds," he says.

The Roman poet Virgil too seems to take a pessimistic view of the power of speech, D'Angour says. "In the face of weapons of war, my songs avail as much as doves in the face of eagles," he wrote in Eclogue 9.

But there was a belief in classical times that the written word had the power to survive "and transcend even the bloodiest events... even if they didn't actually prevail against arms in the short term," says D'Angour.

Napoleon is another who is said to have compared word and weapon. "Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than 1,000 bayonets," he is sometimes quoted as saying.

Again, it's questionable whether these words did actually cross his lips, says Michael Broers, professor of Western European history at Oxford University - but he says the sentiment definitely chimes with Napoleon's views.

"He respected the press and feared it too. He realised all his life the power of literature and the power of the press," Broers says. When Napoleon came to power there were dozens of newspapers in France but he suppressed most of them, sanctioning just a handful of publications.

He also realised that the pen, in his own hand could be a weapon, says Broers. "He knew that he could undermine the allies who had defeated him through his memoirs and he did."

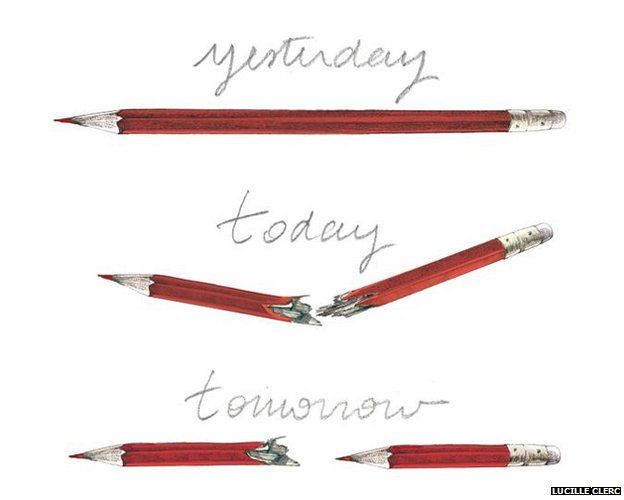

The cartoons published in tribute to the murdered Charlie Hebdo staff carry a range of messages - that the pencil will ultimately defeat the gunman, that one pencil when broken will become two, or that every gun will find itself opposed by many pens. The demonstrators holding pencils aloft are signing up to the same set of ideas.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published8 January 2015