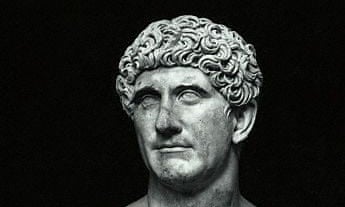

When a senior Vatican official made a call to a tattoo removal specialist, it was not a red-faced cardinal hoping to erase an anchor on his biceps. The Vatican Museum had requested the use of tattoo removal equipment for the delicate removal of dirt particles covering some of its most priceless works.

Reached through one of its Italian associates, Lyntons Lasers, the Cheshire company that supplied the tatto removers, later donated one of its machines to the museum.

Mediaeval sculptures would seem to have little in common with awkward tattoos honouring past lovers, but the process to clean the former and remove the latter can be virtually identical, the company’s chairman, Andy Charlton, said.

The tattoo removal machine uses minuscule pulses of near-infrared laser radiation to remove unwanted particles, breaking up encrustations of pollution, or tattoo ink on skin.

Charlton, whose machines have already been used by numerous art galleries and museums, said the lasers allowed an extremely gentle method of cleaning and removing dirt from very fragile surfaces. “Even from a badly weathered marble surface desperately in need of consolidation,” he added.

The lasers were mostly used to strip dirt from ancient sculptures rather than paintings, Charlton said. “That’s 95% of what they can be used for. With artwork or frescoes it can be done but it’s more difficult when you’re dealing with pigment. The light heats up the dirt and blasts it off, but you want it to be self-limiting, so it doesn’t also heat up the paint underneath. It’s similar with a tattoo, apart from the ink is in the skin – you want to blast that away without damaging the skin.”

Cardinal Giuseppe Bertello, one of Pope Francis’ inner circle of advisers, hosted a private ceremony in the museum’s Pinacoteca gallery in appreciation of the donated equipment, and guides took the company’s executives on private viewings of artworks and on a tour of the pope’s Castel Gondolfo farm, where vegetables and milk are produced for the pontiff’s table.

Catholics may be more at ease with using equipment linked with tattooing than some other branches of the Abrahamic faiths. Judaism interprets Leviticus 19:28 as expressly forbidding tattoos, and Sunni Islam is also against the practice.

But tattooing has never been expressly condemned by any Catholic thinker, according to the Catholic Herald, and can be seen, in that faith, as “a matter of taste, not morals”.

In June 2013 Pope Francis was photographed blessing heavily tattooed motorcyclists who were on a pilgrimage to St Peter’s Square, Rome, for Harley-Davidson’s 110th anniversary.

- This article was amended on 25 June 2015. An earlier version referred to “bicep” where “biceps” was meant.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion