The Sad Legacy of Robert Bork

The late judge didn't have a chance to move Supreme Court jurisprudence. But his failure to be confirmed had a profound and regrettable effect on how we nominate justices today.

The late judge didn't have a chance to move Supreme Court jurisprudence. But his failure to be confirmed had a profound and regrettable effect on how we nominate justices today.

The relentless honesty and arrogant mien of Robert Bork, who has died at 84, during his unforgettable 1987 Supreme Court nomination hearing resulted in two very important things for this nation. First, it precluded the ideologue from becoming a life-tenured justice, which has meant over the intervening 25 years many saving graces for progressives and many bitter disappointments for conservatives. Second, it changed (forever, I suspect) the way judicial confirmation hearings unfold, by encouraging earnest nominees to say to the Senate Judiciary Committee nothing at all candid, specific, or profound about their judicial philosophies or views of the law.

Reasonable minds may argue over how different American law would be today if the Senate had confirmed Bork. The position ultimately was filled by Anthony Kennedy, who has been a diehard conservative in some areas (like economic policy and the First Amendment) and an unabashed liberal in others (like gay rights and restrictions on capital punishment). My best guess is that Bork would have been a conservative activist very much in the manner of Justice Antonin Scalia, a loud and consistent vote to roll back precedent not just to pre-Warren Court positions but to the Lochner-era sensibilities of a century ago.

But no reasonable person today can contend that judicial nomination proceedings are more insightful and productive in the wake of the Bork hearing. Throughout the long history of court appointments, confirmations had rarely been detailed affairs. In 1962, for example, John F. Kennedy appointee Byron White was questioned by the Senate Judiciary Committee for all of 11 minutes. In fact, it wasn't until 1925 that a Supreme Court nominee (Harlan Fiske Stone) even appeared before the committee and it was another 14 years before a second (Felix Frankfurter) did so.

So the Bork hearing didn't reverse a century of transparency in the process. But it certainly assured that no such transparency and candor would ever come again. The self-defeating lesson which official Washington took from the political savagery of the 1987 proceedings was that nominees were better off saying nothing publicly about their views of the law and were better off serving up empty platitudes when backed into a corner by their Judiciary Committee inquisitors. Sadly, you can draw a direct line from Bork's experience to John Roberts' patronizing "umpire" analogy during his 2005 confirmation hearing.

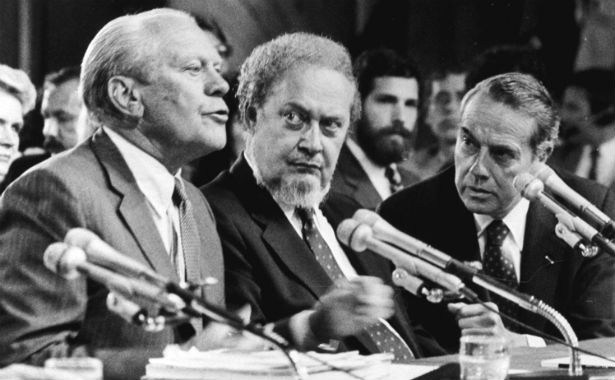

Even if Bork had never been "borked" (verb: to have one's nomination to high office be subject to zealous political attack), he would have been a colossal figure in the law. He was a former federal appeals court judge. He was a Yale law professor. He was a Justice Department official during the Nixon Administration; it was Bork who was left standing at Justice on the evening of October 20, 1973 following the "Saturday Night Massacre," which saw the firing of Archibald Cox and the resignation of Elliot Richardson. Most recently, he was a legal adviser to the campaign of Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney.

Had Romney won, and had Bork survived, the old judge finally would have been able to exact a measure of revenge on those who had long ago denied him his ultimate goal. (That Romney chose this divisive figure to counsel him on judicial policy and court nominations says more about the candidate than it does about the judge). But Bork already had outlived many of his old tormentors, including Senator Edward Kennedy, the Democrat, and Senator Arlen Specter, the Republican. The three of them were and always will be intertwined; characters in a drama that sharply shaped both the Supreme Court and the way we pick its justices.

In any event, with Bork's death and President Obama's reelection, we will never know how far the jurist's influence might have gone with a Republican presidential victory. And so a man with an immense legacy in the law will be forever known not for what he achieved but for what he did not; not for the stark philosophies of privacy and equal protection he would have tried to impose on the nation, but for an informal rule of judicial nominations that compels candidates forevermore not to share with the American people what they really think about the Constitution and the Supreme Court's precedent. He is a hero to some, a villain to others, but for a brilliant man who was first of all direct and forthright, that's a terribly sad legacy, indeed.