My feet are slipping, and I’m already so gripped! Is this tool going to hold? Stick, damn it! This ice is shattering everywhere. I don’t want to fall; I REALLY don’t want to fall. Shit! Did the entire column just shift? This whole thing is coming down, and I’m attached to it!

Four years ago, I was in Vail, Colorado, climbing a spectacular 90-foot curtain of ice at the Fire House. It had formed a thin, fragile pillar running from the ground to the top in one continuous, beautiful blue column. An ice climber’s dream.

Things were going well as I moved up the route; it was a challenging climb, but not at my personal limit. I climbed 50 feet up, placing several ice screws and feeling calm and focused. Then, all of a sudden, a tremendous crack shattered the stillness and my focus, like a cannon going off in a library. Looking down, I was horrified to discover the entire pillar had broken horizontally just above my knees. Now, both frozen masses were perched like two school buses balancing nose to nose.

The gravity of the situation registered immediately in my body and mind. I was motionless for a few seconds in hyper-awareness. The silence that felt expansive earlier now seemed to close in on me. Time slowed, and I watched for signs of the whole climb collapsing—with me on it. My mind was a white-hot fury of input, and an electric heat ran through me. Thoughts fired in disjointed fragments: Screw placements? Belayer out of harm’s way? How far to the top? It finally occurred to me that I was attached to a 100,000-pound ice bomb that was about to explode. I started to shake uncontrollably, the vibration pulsing out to my grip on the ice tools. I had never experienced anything like this, and there was nothing I could do to stop the shaking. I knew I had to control it or there would be fatal consequences. After what seemed like an eternity, I began taking deep breaths and forcefully exhaling the air to try and take command of the sinking ship that was my nervous system. It started working, and a plan took shape.

I focused my mind on small, specific tasks: Yell to belayer to unclip and move to safety. Untie my own knot with one hand. Toss rope down. I thought every second that passed was going to be the end, but I persisted in focusing in on each little step. The realization that I was now 50 feet up a WI5 pillar without a lifeline sunk in, and I stopped to take a few more breaths. The panic finally gave way to clear, pragmatic thinking. I need to get off this piece of ice, and I need to do it now. I reminded myself, Matt, you can climb this without falling, without getting pumped. You can climb this perfectly. One move at a time—swing, stick, pull, repeat, I pulled over the lip 15 minutes later. Safely on top, I inhaled deeply for what felt like the first time in forever.

The Science

So what the hell was happening to me throughout this ordeal? Psychologist Peter A. Levine, Ph.D., who has studied stress and trauma for 35 years and served as a stress consultant for NASA, says there are three distinct stages to any traumatic experience, which every climber has gone through at some point, whether getting Elvis leg five feet above a bolt, flailing on the topout of a 25-foot boulder, or running it out over a questionably placed cam. First, there is an event. Second, there is shock. Third, there is the body’s response. This response can take three forms: fight, flight, or freeze. Fight or flight confronts the threat directly, like seeing a bear and running away. Both of these responses discharge the energy that accumulates in the body. More common in climbing, the freeze response can be complex since you can’t exactly run or fight when you’re faced with a hard move above your bolt. Unfortunately, that energy can transform into a sort of full-body handcuff that paralyzes your entire being.

The body’s response comes from the activation of the sympathetic nervous system that floods the body with catecholamines (aka adrenaline). While these hormones can enhance a body’s ability to deal with certain situations (brain on high alert, muscles tensing, etc.), it can be dangerous in climbing, which requires mindfulness and technique. The ability to make and execute calm and calculated technical decisions can get totally hung up by the subsequent freeze response. According to Levine, if you are unable to discharge the built-up adrenaline, you won’t be able to move forward—or up. In such cases, Levine describes that the body has a natural shaking release. This is what happened to me. My body was overloaded with an overwhelming charge from my sympathetic nervous system, and the shaking allowed me to purge it and move on. The shaking, which at the time made me feel out of control, was actually the fear (adrenaline) leaving my body. After the shaking, instinctive responses (and some active self-talk, which we’ll discuss later) got me back on course.

Real vs. Perceived Danger

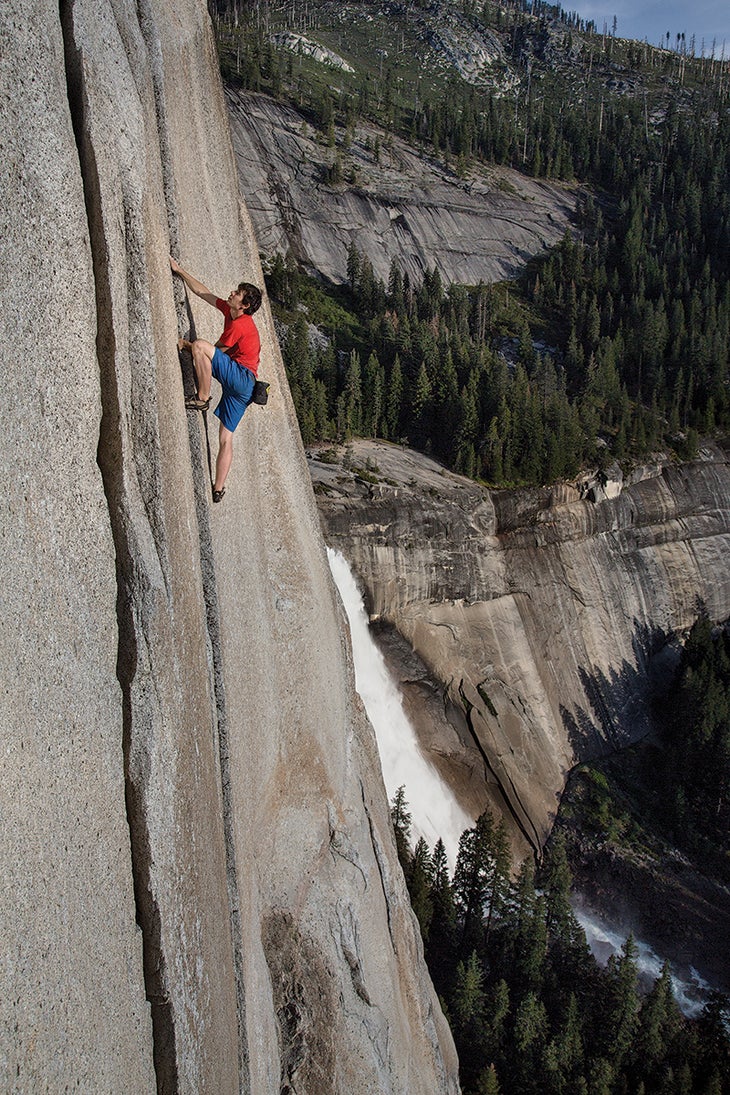

As the greatest free soloist of our generation, Alex Honnold believes most climbers confuse the feeling of fear with experiencing real danger. “A combination of factors makes people feel fear, then they assume that the fear means it’s dangerous,” he explains. “I think it’s important to untangle the various threads that lead to the feeling of fear.” A clear example of this is watching a scary movie: You sit safely in the living room, experiencing the physical and emotional components of fear (sweaty palms, racing heart, anxiety), but you’re not in any real danger. However, distinguishing between experiential fear and actual risk is more difficult while hanging on the side of a cliff, so it’s important to know the true, real risk of a chosen adventure before you embark. Then, when you’re faced with the fear response, take a minute to evaluate what caused it. Is it bad weather moving in or loose rock above you? That’s real danger. Is it the fact that you’re a few feet above your bolt or you’re doing hard moves on toprope? That’s perceived danger.

Honnold employs a sense of cautious realism and pragmatism with his own ascents by examining two factors: the potential consequences (e.g., falling to your death) and the probability of it happening (e.g., low if you’re on toprope). This means that if you’re bouldering at your limit five feet off the ground, the probability of falling may be high, but the consequence is so minimal that the risk is somewhat negligible. The inverse situation would be if you’re a 5.12 climber soloing 5.2 terrain high off the ground. The consequence is high, but the probability of a fall is so low that, again, the risk probably seems acceptable. The real danger in both examples is low.

Assessing and Trusting Ability

It would be silly and, quite frankly, life-threatening to reason that just anyone could employ Honnold’s rationale to justify free soloing El Cap or Half Dome or Moonlight Buttress, because the true level of risk is dependent on something unique to each individual climber: personal ability. Accurately assessing your personal ability is an important part of proper risk management, but this may not always prove easy. (Of course, it does not determine the probability 100%, as there are always objective hazards like weather or rockfall.) Underestimating will leave you stuck in the potentially boring middle ground of not progressing, while overestimating could put you in a dangerous or fatal situation. Be realistic, base it on your climbing experience and mileage, and if you do have to guess, do it in a low-consequence situation (sport climbing, toproping, etc.) as often as possible so you can get a better idea of your ability.

One strategy to assess your skill level effectively is to recall prior, similar experiences. The trick is to recall the facts rather than the emotions. Don’t think about how you felt about the comparable climb, but rather analyze the outcome of the event, comparing factual details while carefully avoiding emotion. If you regularly climb 5.9 on gear without falling, it would be fair to say your experience will be similar on most comparable routes.

Don’t compare apples to oranges—just because you flailed on a 5.10 slab doesn’t really say anything about your potential performance on an overhanging 5.10. Evaluate your memory as rationally as possible by differentiating between real and perceived dangers you experienced on past routes.

When world-class free soloist and BASE jumper Steph Davis is faced with a big jump or climb, she knows it’s within her ability, and she fully trusts that ability. This allows zero mental space for doubt or fear to slip in and send her on a downward spiral of anxiety. The best perform so well because they know, without a doubt, that they are capable of attaining an objective, and then they fully believe it when performing. Davis purposely empties her mind beforehand of negative mental dialogue, which she says also helps her enjoy those pursuits even more: “When I’m not being held back by fear, I’m free to really enjoy climbing, and I’ve spent a lot of time figuring that out.”

Avoid the Fear State Altogether

All the pro climbers I interviewed said that completely avoiding the fear state was the single most effective way to perform in high-intensity situations. Chris Schulte, V15 boulderer, first ascensionist, and highball guru, says, “The minute you get scared you’ve done yourself the worst damage, because your body is just going to take over from there. If you’re scared enough, you’ll lose control, and you won’t be able to get it back. Everything tightens up, you start over-gripping, and your whole being retreats within itself.” The best and boldest climbers consciously avoid triggering their fear response because they understand the danger of falling into their body’s natural fight-flight-freeze response. “I’ll have some little thing happen, and I think, That’s scary,” Honnold says, “but I feel like I’m pretty good at clamping it down and not letting it go down the path of getting more and more scared until I fall apart.” Here, Honnold stops the negative self-talk (“I can’t do this. I’m going to fall. This is scary.”) before it triggers the emotional response of fear. He doesn’t allow the story of falling to enter his mental dialogue at all, thus completely avoiding one of the precursors to fear.

One way to avoid this state is being fully prepared and equipped to handle the objective. Before alpinist Kelly Cordes was blasting up Great Trango Tower, he was a nationally recognized collegiate boxer. He recalls standing in the ring before his first bout, hoping his opponent wouldn’t show up. He was filled with fear of failure and of the unknown. After four years and dozens of fights, Cordes stood in that same situation awaiting the arrival of his opponent. Even though the danger of the situation was the same—walking into a ring with a man who is trying to hurt you—his level of experience and preparedness had changed his perception of the danger. He was ready, he was trained, and he had been there before. He says, “I was standing there thinking, This guy better show up!”

When you’re prepared and well-practiced, you have no reason to doubt yourself. It’s not about closing your eyes and jumping into the unknown. It’s about having eyes wide open to the dangers around you but knowing that you’re as ready as you can be. Trust in your training and preparedness will give you the required confidence to apply your skills to the task at hand. Then when you’re performing, pay close attention to possible trigger thoughts as they appear. Stopping them before they manifest into negative emotional responses is paramount.

Certified sports psychologist Dr. Lisa Lollar, who coaches professional athletes in realizing their goals, says, “You have to believe and know that your skills and the challenge match.” Then while performing, the pros work consciously and in the current moment. They focus on the task at hand rather than the outcome, staying present rather than thinking too far into the event or about the finish. Honnold says, “You might have moments along the way where your body is scared, but you know that you can [accomplish the climb]. To me it takes [a certain kind of] rationale to look at it from the outside and say, ‘I’m scared, but I’m still holding on. I’m still fine.’ ”

Coming Back From Fear

So, what if the plan of avoiding the fear response fails? Like my incident in Vail, everything can be fine until some objective hazard or mistake triggers that feeling. When it comes to managing fear and improving performance in climbing, it’s critical to be able to transition out of fear. Imagine a sport climbing scenario where you’re several feet above a bolt. You’re breathing hard and start to over-grip, body tensing and locking up. Ultimately, you either need to keep climbing up or downclimb—or else you’re gonna take the whip anyway. Transitioning out of fear is crucial to making an informed decision as to what you should do next. As we’ve seen, fight, flight, and freeze are a limited repertoire, especially in climbing, where calm is the name of the game.

Fortunately, we humans have something special to combat these sometimes irrational, limited responses. That’s the prefrontal cortex, and it gives us the ability to inhibit the fear response of the amygdala, which is part of the “lower brain.” The prefrontal cortex is the rational, conscious part of our brain, the part that makes us civil and human by its ability to reason and filter out our animal instincts. Without the ability of our prefrontal cortex to reason with the instinctual amygdala, we’d never get off the ground in the first place.

Lollar helps athletes overcome the fear-ridden brain to arrive at a place of mental clarity and presence that optimizes performance, and she uses psychological tools like centering, visualization, and self-talk. These bring the prefrontal cortex back online, calming the emotional and instinctive parts of the brain.

Visualization

Visualize as much as you can before you even get off the ground, while lying in bed at night or driving to the crag. The basic idea is to imagine and clearly see yourself completing each move with ease. Lollar says it works best when you add as much detail as possible: how your body feels pulling over the crux, the breeze on your face, fingers clamping down on the cold, gray granite. Go through each move step by step from bottom to top.

This mental rehearsal is surprisingly similar to physical practice; you can actually perform better without lifting a finger. You are also likely to experience an improved sense of confidence after visualizing, which will decrease your risk of slipping into the full-fledged fear response. This technique can encompass more than just your physical experience on the climb, too. Think about how you want to feel on the route in addition to how you want to move. I imagine myself staying calm and devoid of panic, should a foot slip or I fumble the beta on a specific move during a free solo. I visualize myself letting the error pass without any internal reflection or unnecessary mental dialogue, keeping my focus on the moves in front of me.

Centering

Best done right after coming out of the initial fear flood, centering involves paying conscious attention to breathing and bodily sensations. Lollar says staying focused and avoiding distractions are critical to performance. Centering helps the athlete stay in the moment and release past and future thoughts, worries, and plans. When Cordes feels the “oh shit” fear welling up, he says, “I zoom in and focus on each move, each motion, and I don’t get overwhelmed by the bigger picture.”

Lollar recommends practicing centering regularly so it can be there when you need it. The next time you’re climbing, see how much of your attention you can bring to the present moment. Notice each inhale, exhale, and the sound they make, feel for the pulse in your chest, and observe the way the rock feels under your fingertips. Using this will bring you back to the present moment, which is where you need to be to perform. The trick here is to practice this when you’re not scared. Observe yourself when you’re calm and climbing well, so it will be easier to gain presence when you’re entering a dangerous move or hazardous terrain. Repetition is the father of learning. Steph Davis says, “Careful, this kind of mental and physical training takes practice. Everyone knows you can’t get strong fingers in one campus board session; it’s the same with your mind. The important thing is to realize that and take the first step down the road of learning.”

Self-talk

Use self-talk at any time to quiet the amygdala, awaken the prefontal cortex, and regain your calm. Either out loud or in your head, talk to yourself. When you hear the fear response (“That’s not right. I’m scared.”), recognize those words for what they are—products of the part of your brain responsible for generating fear—and force your brain to say something else. Make it simple: “I’m fine” or “I can do this” or “I got it.” If you are struggling with negative thoughts and can’t break out of the cycle, force yourself to smile and hear yourself say, “I’m OK.” It might be all you need to relax back into your flow state.

Honnold employed this method on his 2012 solo of the Yosemite Triple: “There were a half-dozen times when something unexpected happened, and I had that moment of Oh, that’s not right. I was scared, but each time I wouldn’t let it get to the next level. I would shut it off. I would say, ‘I’m fine,’ and keep moving.” Schulte employs similar techniques: “There are all these little monsters you can get rid of with just the right words.”

While fear can seem like the enemy of any climber, I’ve learned that there are several things you can do before leaving the ground to mitigate its effect. Step 1: Do risk and ability assessments. Step 2: Have confidence in your ability and preparedness to avoid slipping into the fear state. Step 3: Push negative thoughts out of your mind the moment you feel them start to pop up. Step 4: Employ visualization, centering, and self-talk to prevent or come out of the fear state. Step 5: Review the climb and recall the things you did well. Lollar suggests focusing on actions, thoughts, and behaviors that helped you perform well.

It’s been a few years since I was on that particular ice pillar. Looking back, there is little I would have—or could have—changed; luckily things worked out in my favor. That doesn’t mean I rack up my experience to good fortune and move on. Instead, I have used that experience as a jump-start for my mental training. These days I don’t look at my emotions as random and uncontrollable, but rather a biological process that can be mastered. So when those fear moments do arrive, you’re more than ready.

On a recent 5.11 free solo in Golden, Colorado, I sat at the bottom of the climb thinking about how quickly panic sets in. Something as simple as an insecure foothold or a single moment of uncertainty can trigger a flood of negative self-talk and then the biological, chemical response that can so profoundly affect your performance. I then imagined myself handling that experience calmly, breathing deeply, and saying to myself, Relax, you can do this. I still get scared—hell, what climber doesn’t?—but now I’m better equipped to keep my cool, and that’s made all the difference.

Denver-based pro climber, writer, and guide Matt Lloyd has been climbing for 15 years, free soloed 5.12d, survived heinous weather in the high mountains of the Cordillera Blanca, and led 5.13 R routes, but he has yet to conquer his biggest objective ever: his own mind.

This article originally appeared in Climbing in 2014.