In June, 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a memorandum to the War Office calling for the creation of an airborne unit. Churchill had been impressed by Germany’s use of parachute and glider troops during their invasion of France and the Low Countries, and felt Britain should have a similar capability.

It took time for the Airborne Forces to become fully developed. No. 2 Commando, consisting of 500 men, was given parachute training in the summer of 1940. Airborne Forces were then expanded, and in September, 1941, 1st Parachute Brigade was created. No. 2 Commando was renamed 1st Parachute Battalion, and 2nd and 3rd Parachute Battalions were established. The new Battalions recruited soldiers from all across the British Army. In those early days, the only Airborne-specific insignia was the parachute brevet (or “jump wings”); the famous maroon beret had not yet been adopted, and the new paratroopers continued to wear the insignia and headdress of their previous units.

2nd Parachute Battalion’s first Commanding Officer, Lt. Col. Edwin Flavell, gave each of his officers a bright yellow lanyard to wear on the left shoulder, to distinguish them from officers of the other two battalions. The “other ranks” (enlisted personnel) decided they wanted to wear the yellow lanyard, as well. However, they had to make their own, which required a certain amount of improvisation and ingenuity.

The lanyards were made by cutting a length of rigging line, made of white silk or nylon, from a parachute after a training jump. This cord was braided or tied into a lanyard; those unskilled in making it themselves begged help from friends.

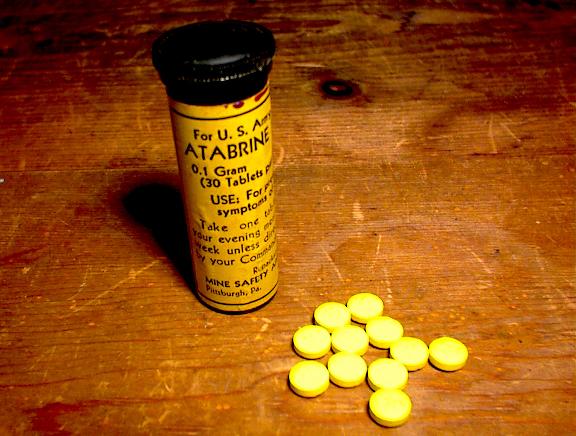

The most ingenious part of the process was dying the lanyard. Troops sent to the tropics were ordered to take Mepacrine, also known as Atabrine, a bright yellow medicine intended to fight malaria. Continued use of this drug was known to turn the skin and eyes yellow; therefore, it was seen by the troops as a logical dye. Mepacrine pills were acquired, then ground up and dissolved in water to turn the white lanyards a deep yellow or golden color.

US-issued Atabrine; the British called it Mepacrine. It was a common anti-malaria drug in the 1940’s, but continued use turned the eyes and skin a yellow color.

Intentionally damaging a parachute and misusing medical supplies were both serious offenses. The officers of 2nd Parachute Battalion would normally have punished anyone guilty of these military crimes. However, they turned a blind eye and even unofficially encouraged the behavior. The yellow lanyards became prized possessions; the men were immensely proud of their Battalion, symbolized by the yellow lanyard.

Eventually, 1st Parachute Battalion adopted a dark green lanyard, and 3rd Parachute Battalion adopted red. However, their creation did not seem to have the same creativity behind them.

By the time James Sims joined 2nd Parachute Battalion in 1943, it was a veteran unit, having recently returned to England after bitter fighting in North Africa and Sicily. Airborne Forces had expanded to two Divisions, the 1st and the 6th, and the maroon beret had been adopted for all Airborne Forces, including glider troops. The Parachute Regiment had been formed officially, with its own insignia and cap badge. However, in 1st Parachute Brigade, the colored lanyards were still in use to distinguish the different Battalions.

As described in Sims’ book Arnhem Spearhead, the yellow (or golden) lanyard was still made the same way as in the early days of the Battalion. Sims was given his when he first joined the Mortar Platoon of S Company.

They laughed at my discomfiture but suddenly one of them said, ‘Here, put this on.’ He handed me a beautiful gold lanyard, obviously made out of parachute nylon rigging line, the removal of which was a court martial offence. This gold lanyard was worn only by the 2nd Battalion and was produced as follows.

After a jump a para would cut off a rigging line and secrete it about his person. Back at camp he would persuade someone skilled in the art to plait it into a lanyard. He would then dissolve a mepacrine tablet in a saucer of water in which he would place the lanyard, leaving it overnight. In the morning he would have a beautiful gold lanyard. No one could recall the genius who first devised this unauthorized use of medical supplies, which was based on the idea that if these tablets could turn a man yellow they would do the same for nylon. Because of this practice the 2nd Battalion were known in the First Para Brigade as the Mepacrine Chasers. The 1st Battalion had dark green lanyards and the 3rd red. Everyone in our battalion had a ‘larny’ lanyard, as it was known, and it was very highly regarded.

I belong to a living history organization which portrays B Company, 2nd Parachute Battalion, and it is humbling to read about the extraordinary men whose history we try to preserve. I gave a copy of Arnhem Spearhead to a close friend as a Christmas present. Being an avid sailor and generally good with knotting and braiding, he decided to make a number of lanyards for us. He used nylon parachute cord, and experimented with different formulas and concentrations of “RIT” dye. Previously, I had worn a machine-made yellow lanyard from a surplus store; replacing it with a hand-made lanyard given to me by my friend is much more meaningful, and much closer to what the original lanyards represented.

Hand-braided, hand-dyed yellow lanyard, made based on the description in James Sims’ Arnhem Spearhead.

Arnhem Spearhead is out of print, but copies are often available online. Lt. Col. Flavell’s issue of the yellow lanyard to the officers of 2nd Parachute Battalion was recalled by the Battalion’s first Adjutant, and later, most famous commander, John Frost, in the book Without Tradition: 2 Para 1941 – 1945, by Robert Peatling.

More information on Maj. Gen. John Frost and 2nd Parachute Battalion may be found in an earlier blog post, here.

Without Tradition: 2 Para 1941 – 1945 by Robert Peatling

Sources

Peatling, Robert

Without Tradition: 2 Para 1941- 1945

Pen & Sword Books, Ltd., 1994

Sims, James

Arnhem Spearhead

First published by Imperial War Museum, 1978, Republished by Arrow Books, Ltd., 1989

Pingback: Film Review: A Bridge Too Far | Colour Sergeant Tombstone's History Pages

Gday , I still have my dads lanyard, His Name is William Frederick Mason first brigade 2nd battalion c company mortars, he was captured on the 21st September 1944 and released in May of 1945 , he worked down the pits in Leicester most of his life , he came to live in Perth Western Australia in 1990 and had a wonderful last few years , he died at the age of 94 from black lung caused from working down the pit , he never smoked and drank very little , he was the best dad ever , my forever Hero, Garry his eldest son ,.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

If you have a photo, I would love to see it!

LikeLike