The Formula 1 message boards have recently been abuzz with discussion of the Rosberg/Hamilton collision at Spa 2014. From these discussions it has emerged that many fans are not well acquainted with the rules of racing, or are confused regarding which rules apply to which scenarios. This is not particularly surprising, since the rules of racing are complex, notoriously filled with gray areas, and covered in only a very limited and inexact form by the FIA Sporting Regulations. There is little effort on the part of the sport’s regulators to communicate and clarify these rules for fans and I could find no comprehensive guides online.

To even begin to discuss the Rosberg/Hamilton accident, we need to have a solid understanding of the rules of racing. I will therefore cover how the rules apply to the most common on-track scenarios, before considering Rosberg and Hamilton’s interactions this year as a case study. This analysis is unlike my previous mathematical analyses, but I think it’s an important topic to cover.

For this post, I will be drawing on a variety of sources that I have read or been exposed to over the years, including the sporting regulations for Formula 1 and various other forms of motor racing, the consensus judgments of experienced Formula 1 pundits, as well as many guides for professional racing driving. Once you have developed a basic foundation for assessing corner ownership, it becomes easy to compare and discuss the details of different incidents.

“All the time you have to leave a space!”

Let’s begin with the simplest possible case: two drivers battling it out on a straight.

1. The one-move rule

When one driver is completely ahead of another on a straight, they are permitted to make a move in one direction. This move can be of any size, within the track limits, and the move can be made as slowly or as quickly as the driver likes — they can jink suddenly to one side or they can spend an entire straight gradually shifting across the track. This rule is stated under sporting regulation 20.4

20.4 Any driver defending his position on a straight, and before any braking area, may use the full width of the track during his first move, provided no significant portion of the car attempting to pass is alongside his. Whilst defending in this way the driver may not leave the track without justifiable reason.

More than one change of direction on a straight is called weaving and is NOT permitted. This rule is stated under sporting regulation 20.3.

20.3 More than one change of direction to defend a position is not permitted.

The one-move rule holds true whether the defender’s moves are designed to block the attacker or to stop the attacker from keeping in the defender’s slipstream. The precedent for the latter case is Lewis Hamilton’s weaving in front of Vitaly Petrov at the 2010 Malaysian Grand Prix, for which he received a warning from the stewards.

When a defender makes their one move, the distance and closing speed of the attacker may also be considered by the stewards. If the attacker is closing quickly and is only a short distance behind, then they may not have time to evade a sudden move into their path. It is at the stewards’ discretion whether or not to punish late defensive moves under sporting regulation 20.5.

20.5 Manoeuvres liable to hinder other drivers, such as deliberate crowding of a car beyond the edge of the track or any other abnormal change of direction, are not permitted.

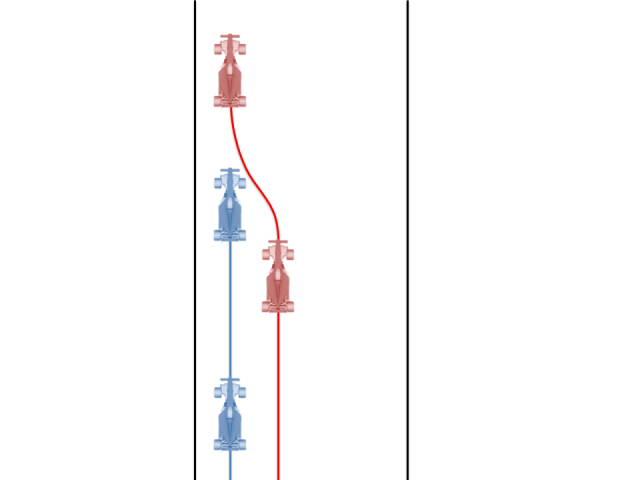

2. Taking the one-move rule to its limits

The one-move rule seems totally umambiguous, with no possible gray area to exploit. However, drivers have often bent the rule by arguing that their second move is part of their racing line for the corner that follows the straight. There are two ways in which this can happen.

The first is when the defending driver makes their first move to the inside and then they pull back towards the outside of the track to pick up a more favorable racing line at corner entry.

This move is seen very frequently and is considered acceptable with one important caveat: when the defender moves back to the outside, they must leave at least one car width between themselves and the edge of the track, allowing the attacker to potentially run deep around the outside. This rule is stated under sporting regulation 20.3, which was formally clarified after Michael Schumacher’s controversial defense against Lewis Hamilton in the 2011 Italian Grand Prix.

This move is seen very frequently and is considered acceptable with one important caveat: when the defender moves back to the outside, they must leave at least one car width between themselves and the edge of the track, allowing the attacker to potentially run deep around the outside. This rule is stated under sporting regulation 20.3, which was formally clarified after Michael Schumacher’s controversial defense against Lewis Hamilton in the 2011 Italian Grand Prix.

20.3 Any driver moving back towards the racing line, having earlier defended his position off-line, should leave at least one car width between his own car and the edge of the track on the approach to the corner.

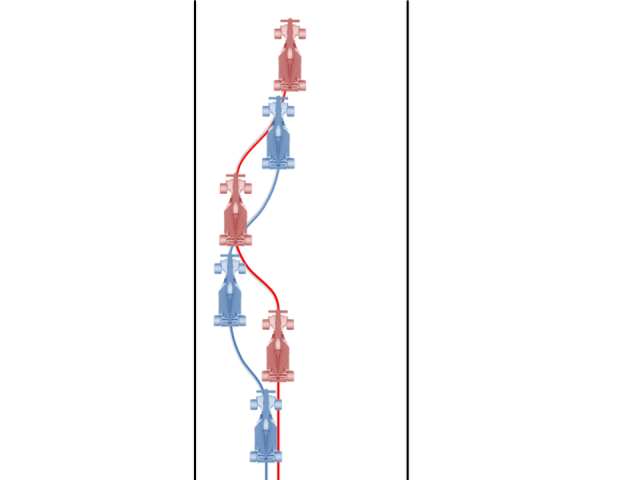

The second case occurs when a defender moves to the outside then cuts back to the inside to negotiate a kink in the straight. A famous example is Michael Schumacher’s defense against Damon Hill between Raidillion and Kemmel in the 1995 Belgian Grand Prix.

Schumacher moved left to block Hill, then immediately turned back to the right to take the inside line through Kemmel corner.

Is this one move or two moves? It’s a marginal case, because corners like Kemmel are gradual enough to almost be considered part of the straight, much like the Monaco start/finish “straight”. This makes it difficult for the defending driver to justify that they needed to pull all the way across to hit a traditional apex, but the case is certainly debatable. This is the first (but not the last) case we’ll see of some theoretical gray area in the rules.

3. Racing alongside another car

When one driver is completely ahead of another on a straight, either can move with impunity within the width of track. Things change when there is any overlap between the cars, because lateral movement could cause a collision. If two cars have any parts alongside one another, each driver must respect the space occupied by the other car. It does not matter who is ahead, nor how far they are ahead, they may not initiate a move into the other car. Both drivers have the right to continue driving in a straight line unimpeded. This rule is stated under sporting regulation 20.4.

20.4 Any driver defending his position on a straight, and before any braking area, may use the full width of the track during his first move, provided no significant portion of the car attempting to pass is alongside his. For the avoidance of doubt, if any part of the front wing of the car attempting to pass is alongside the rear wheel of the car in front this will be deemed to be a 'significant portion'.

Situations like Sebastian Vettel driving into the side of Mark Webber at the 2010 Turkish Grand Prix fall foul of this rule; since the move happened on a straight before any braking zone or corner, Vettel is completely at fault.

Theoretically, cases can arise where two drivers simultaneously deviate from moving parallel to the track, causing their paths to intersect. In this case, both drivers would share the blame, but in practice moves are very rarely truly simultaneous.

Very aggressive bullying of another driver on a straight, like Michael Schumacher on Rubens Barrichello at the 2010 Hungarian Grand Prix, is disallowed. In theory, driving sharply towards another driver does not force them to change their line, but humans being humans this will usually induce a flinch response. How aggressive is too aggressive? This falls into a gray area covered by the vaguely-worded sporting regulation 20.5.

20.5 Manoeuvres liable to hinder other drivers, such as deliberate crowding of a car beyond the edge of the track or any other abnormal change of direction, are not permitted.

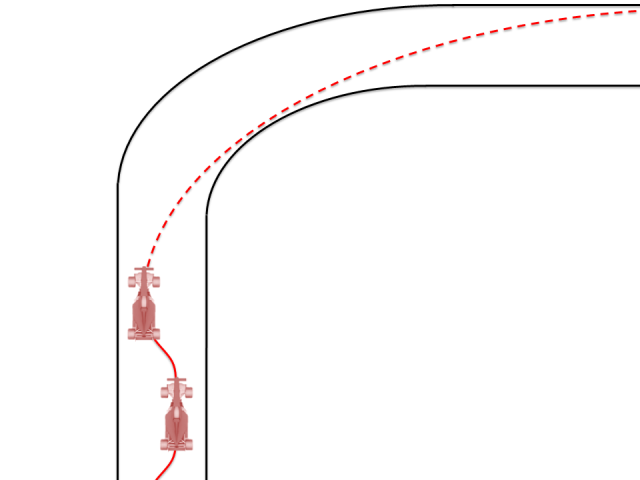

4. Entering the braking zone

On a straight, a defending driver has the right to suddenly change direction, even using the entire track width if they are fully ahead of the attacking driver. The same right does not apply in or immediately before the braking zone for a corner. Sudden changes of direction just before or within the braking zone are considered extremely dangerous, as they can leave the attacking driver nowhere to go. This rule is not stated explicitly in the FIA sporting regulations, but is considered an “abnormal change of direction” under sporting regulation 20.5

20.5 Manoeuvres liable to hinder other drivers, such as deliberate crowding of a car beyond the edge of the track or any other abnormal change of direction, are not permitted.

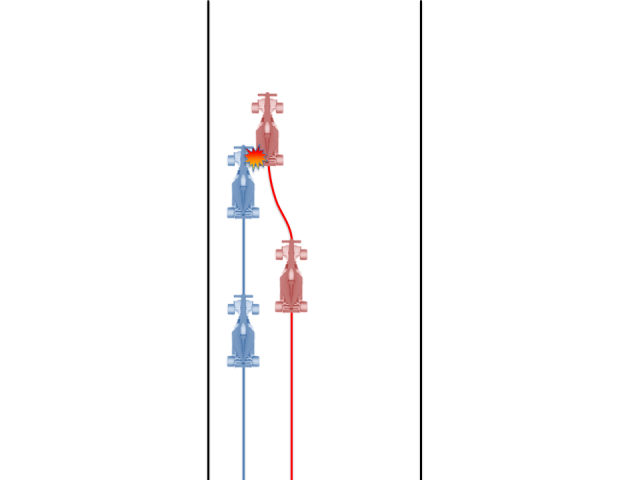

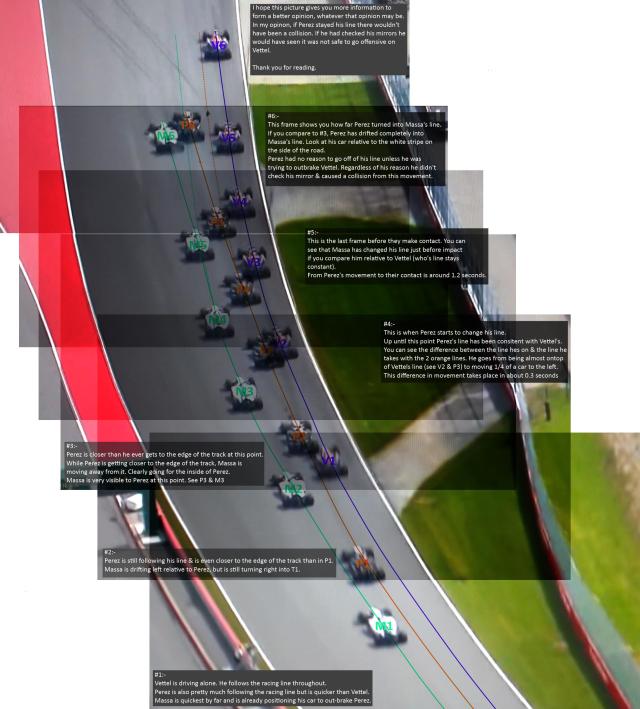

Obviously some change of direction is allowed within the braking zone — the optimal racing line usually involves some amount of trail-braking — so it is up to the stewards to decide what constitutes an “abnormal” amount of movement. In the case of Sergio Perez and Felipe Massa at the 2014 Canadian Grand Prix, the stewards deemed that Perez had made an unusually large change of direction in the braking zone. This was a particularly difficult case to determine, as the normal line under braking curves to the right, and neither driver took a line with uniform curvature (both drivers changed their steering angle at least once). However, careful analysis (posted by reddit user d3agl3uk and reproduced below) showed that Perez was the driver deviating significantly from a normal line under braking.

Brake-testing (i.e., braking earlier than normal to cause the driver behind to take evasive action or crash) is also highly dangerous and frowned upon, but not explicitly mentioned in the FIA sporting regulations.

Who owns the racing line?

The most complicated cases naturally arise once we leave the straight and get into a corner. Both drivers would ideally like to the follow the quickest possible line — the racing line — but there may not be physical space for both drivers to do this. At the same time, drivers would like to obstruct one another as much as possible.

Some of you might be surprised to learn that once a corner begins, the FIA sporting regulations have almost nothing to say, besides ruling that drivers must remain within the track limits! Here, the sporting regulations defer to long-established norms for racing, which may not be known by all fans, and which contain significant gray areas.

5. Disputes over the apex

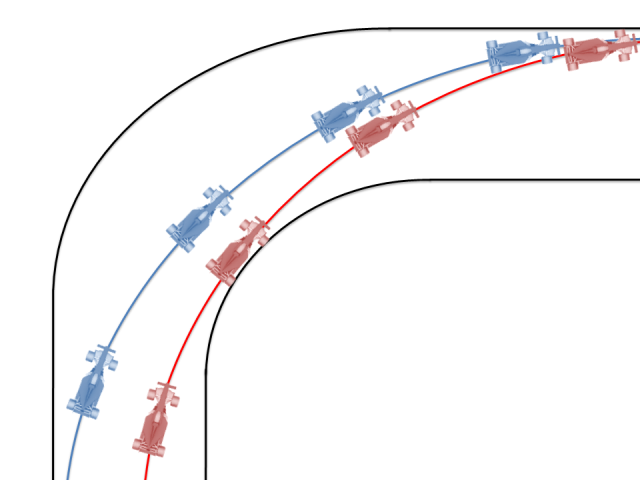

Consider the textbook method for overtaking in a corner: the attacker takes an inside line, gets alongside the defender in the braking zone, and beats the defender to the apex. If the attacker is ahead at the apex, there is no dispute over ownership of the racing line. The defender must yield. But what if the attacker is only partially alongside? Who owns the apex then?

Different racing series have their own criteria for how far alongside an attacker must be to have a claim to the apex. In Formula 1, the norms have been explored and refined over the years as a result of drivers like Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher pushing the boundaries and exploiting any gray areas. Today, it is generally accepted that the attacker must be at least halfway alongside the defender when they reach the apex to have a reasonable claim to this piece of track. Moreover, the attacker should not have achieved this position by carrying too much speed to make the corner — this method is called dive-bombing.

Let’s consider three illustrative examples.

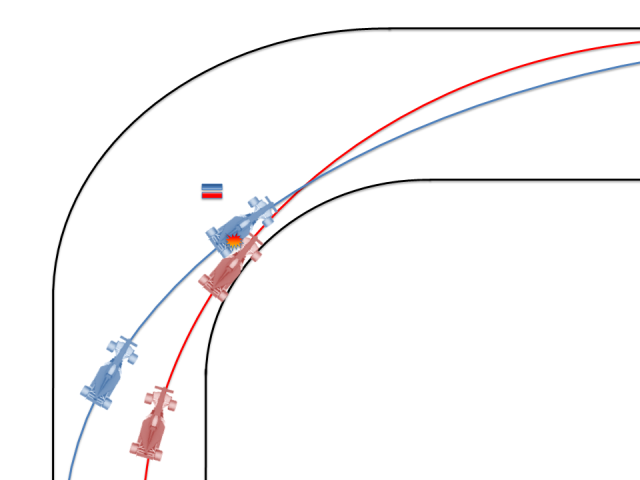

A. Attacker more than half-way alongside

In this case, the attacker is definitely more than halfway past the defender at the apex. The attacker has the right to the racing line. A collision at the apex is entirely the fault of the defender.

B. Attacker less than half-way alongside

In this case, the attacker has only their front wing alongside the defender’s rear wheel. The defender has the right to the racing line. A collision at the apex is entirely the fault of the attacker.

C. Attacker approximately half-way alongside

In this case, the attacker’s front axle is ahead of the defender’s rear axle and the two cars are approximately halfway alongside. Both drivers have a reasonable claim to the apex. If contact occurs, blame will have to be shared. It is in this zone that racing incidents can occur. Ayrton Senna was famous for creating situations just like this, as both attacker and defender, where the other driver would have to decide whether or not to yield to avoid a collision.

Note that this is a not a new or controversial set of guidelines. For example, here is essentially the same set of rules presented in The Williams-Renault Formula 1 Motor Racing Book, published back in 1994.

6. The switch-back

On hairpin corners, an alternative method of overtaking is available, sometimes called the switch-back. If the defending driver takes the inside line, the attacking driver can try to take a wider entry. This results in a later apex, a straighter path under acceleration, and therefore a faster exit.

To deal with this threat, defenders often choose to linger at the apex by delaying their application of throttle on exit. Because the attacker must pass over the defender’s line, this creates an obstruction. Now the attacker is unable to accelerate out of the corner until the defender has done the same, undermining the attacker’s advantage on exit.

Lingering on the apex is considered an acceptable defense, but the amount of lingering that is allowable is not well defined. Clearly a driver cannot come to a complete halt, but beyond that there are no clear guidelines. Here is an example of Barrichello getting irritated with Coulthard for what he considers excessive lingering through the stadium section at Hockenheim in the 2001 German Grand Prix.

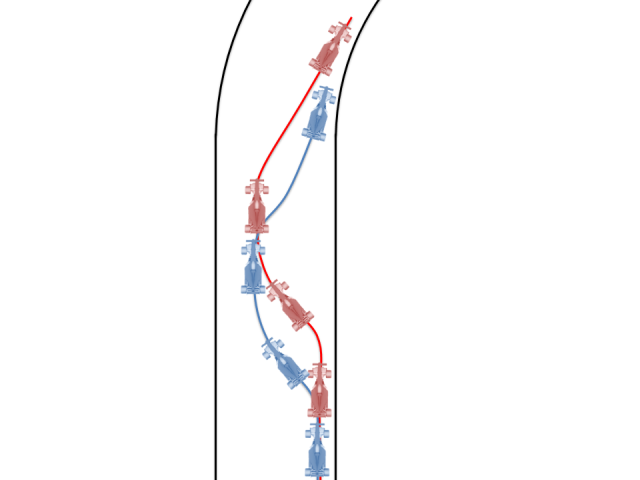

7. Going around the outside

A defender who is overtaken on the inside will sometimes try to hold their position using the outside line. Alternatively, an attacker may try to overtake around the outside against a defender who covers the inside line. Some of the greatest overtaking maneuvers in the sport’s history have been achieved using this method.

If the driver going around the outside is already more than half a car length ahead by the apex, they are entitled to cut in to the inside along the racing line, as per case 5 above. An example is Nelson Piquet’s incredible four-wheel drift around the outside of Ayrton Senna in the 1986 Hungarian Grand Prix.

If the driver going around the outside is not sufficiently far ahead to take the racing line on apex, they can continue on an outside line. In this case, a potential dispute arises at corner exit. The driver on the outside naturally wants to continue their trajectory along the outside, while the driver on the inside wants to take a quicker straighter line by running out to the edge of the track. Who owns that piece of track on corner exit? Who is to blame in the event of a collision there?

Debates over this situation go back many years. In the 1977 Dutch Grand Prix, Mario Andretti stuck it out on the outside of the Tarzan hairpin, resulting in a collision with James Hunt, who was on the racing line and slightly ahead of Andretti. The two drivers saw the event very differently.

I was driving in a perfect line in the corner when he collided and I seemed to go into the air…. It was a mad thing to do. — James Hunt

I was driving on the outside trying to get past when he just drove over my wheel and knocked himself out. — Mario Andretti

Modern consensus would put Andretti at fault. The guiding principle is that the driver on the outside should be at least level (front axle in line with front axle) with the driver on the inside to have a claim to the racing line on corner exit. Depending on the type of corner and the cars involved, either the outside or inside line may be quicker through the corner, meaning the driver on the outside may gain or lose ground from corner entry to corner exit. It is relative positions of the cars at exit — not at entry or apex — that is therefore crucial in judging these cases.

If the driver on the inside is behind at corner exit, they must leave space for the driver on the outside.

If the driver on the inside is ahead at corner exit, it is the duty of the driver on the outside to back out or take evasive action to avoid a collision.

In this case, the driver on the inside is free to drift out towards the outside on exit. While they are expected to approximately follow the racing line — but not exactly, since they enter the corner on a tighter trajectory to a normal racing line — they have some freedom in selecting how aggressively they close out the other driver. Just how aggressive they can be falls into perhaps the most controversial gray area in modern racing. This brings us to the Rosberg/Hamilton incident.

Case study: Rosberg and Hamilton

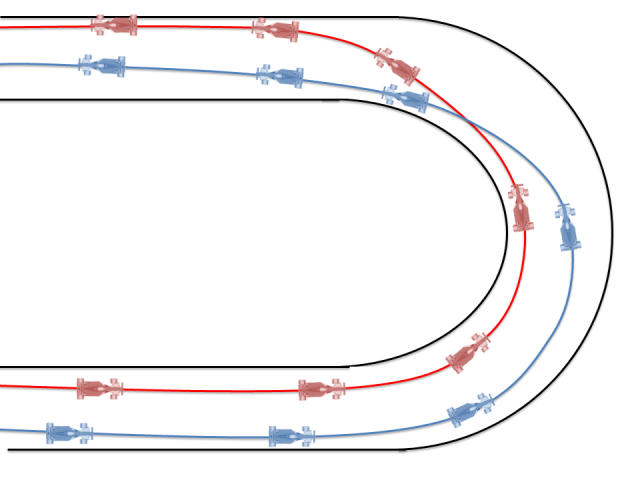

Having covered the rules, I’ll conclude by applying them to some particular cases. In 2014, we have so far had four races in which a Mercedes driver attempted to pass their teammate around the outside. In each case, the driver on the outside has been closed out by the driver on the inside. However, the conditions and the line taken by the driver on the inside have varied from benign to extremely aggressive. I’ll consider each case in chronological order.

Case 1: Bahrain 2014

Several times during the Bahrain Grand Prix, Rosberg found himself on the outside against Hamilton. Each time he was aggressively closed out. The first event occurred on lap 1, shown below.

Hamilton was just ahead of Rosberg at corner entry, but Rosberg gained ground throughout the corner, almost achieving parity by corner exit before backing out. This is right at the threshold where the driver on the outside must be left space, and had a collision occurred, both drivers would have had to wear some of the blame.

A nearly identical situation occurred on lap 52, with Rosberg again getting well alongside Hamilton, as shown in the picture below, but backing out just before exit. Like Senna before him, Hamilton engineered situations where it was up to the other driver to back out to avoid a racing incident where blame would be shared.

A further incident occurred on lap 18, when Rosberg outbraked himself trying to pass Hamilton into turn 1, allowing Hamilton to regain his position with a switch-back. Hamilton took an extremely aggressive line on corner exit to close out Rosberg, with contact only being avoided by Rosberg’s quick reflexes. Rosberg immediately told the team “Warn him, that was not on!”.

Case 2: Canada 2014

Hamilton attempted to pass Rosberg around the outside at the first corner after the start. He was fully alongside Rosberg at the beginning of the braking zone, but Rosberg braked slightly later and thus took a deep line into the corner to close out Hamilton, who was behind by corner exit and yielded.

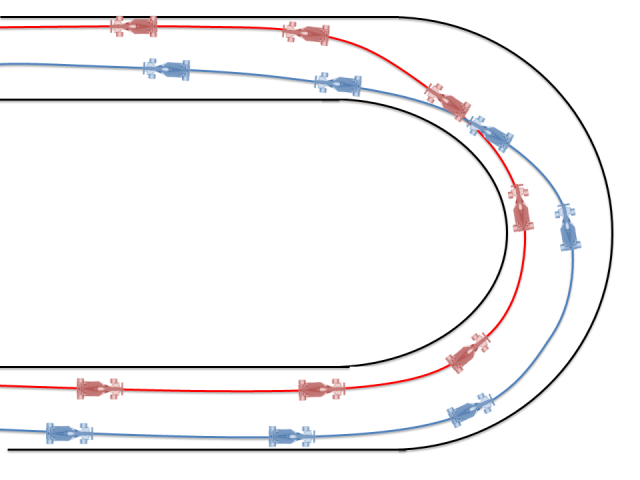

Case 3: Hungary 2014

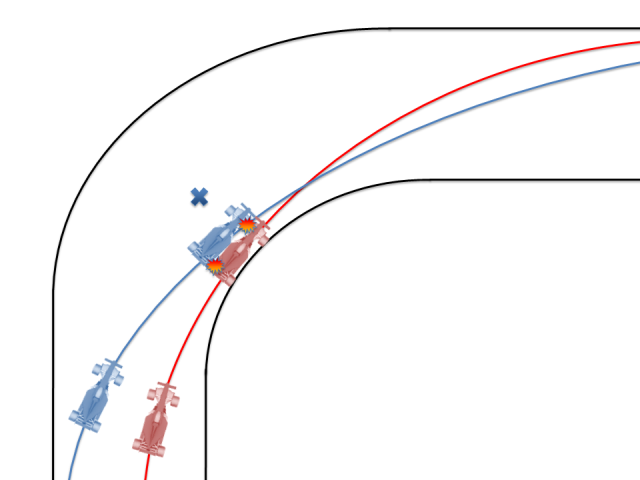

On the final lap at Hungary, Rosberg attempted to go around the outside of Hamilton at turn 2. Rosberg came from very far back, but also had fresh tyres allowing him to maintain a higher cornering speed. Midway through the corner, Hamilton spotted Rosberg’s move and suddenly straightened his wheel to aggressively angle out Rosberg before corner exit. This is getting very close to the limit of what could be considered an acceptable defensive line.

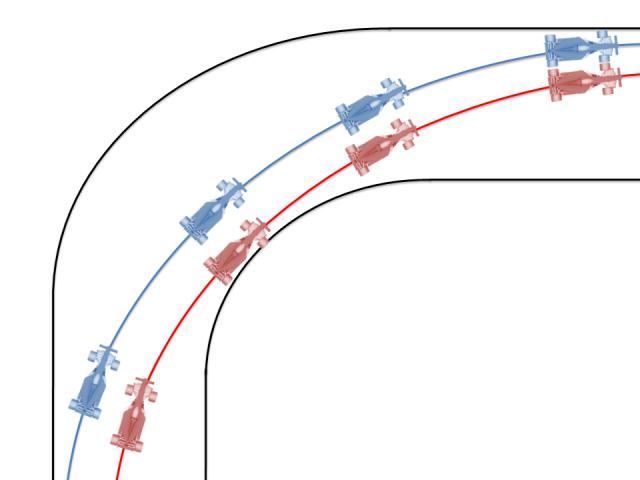

Case 4: Belgium 2014

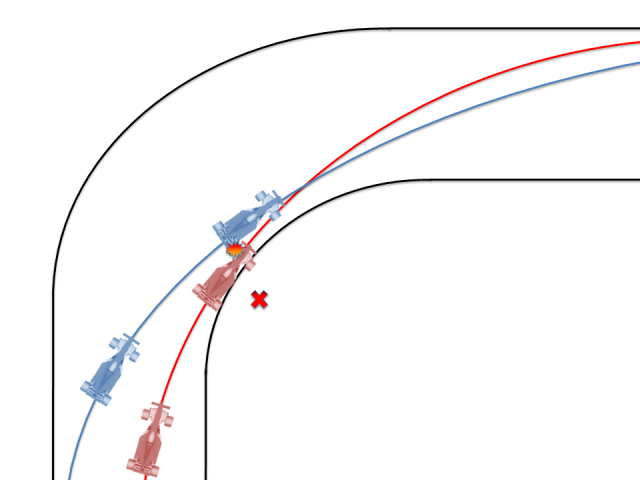

Rosberg was behind throughout the corner and almost a full car length behind by corner exit. Hamilton took a fair line — just slightly more aggressive than the usual racing line. Rosberg jinked left momentarily to make extra room, but then maintained a relatively tight line leaving insufficient space for Hamilton on the line he was taking. This resulted in a front-wing/rear-wheel collision.

Just what was Rosberg thinking here? We have heard from Toto Wolff that Rosberg was not intending to cause a collision, but he was intending to “make a point”. As I have hopefully made clear, there is a reasonable theoretical argument to be had regarding the defender’s role in these types of positions. Just how aggressive are they allowed to be in squeezing out the attacker? Hamilton’s defenses at Bahrain, where he twice closed out Rosberg with their cars approximately level and nearly caused contact with another aggressive line, as well as his defense at Hungary, where he suddenly pitched his car onto a different line to close out Rosberg, were wading deep into this gray area.

Still irritated by Hamilton’s earlier defenses, it seems Rosberg wanted to draw a line in the sand in Belgium. This time, Rosberg chose to pick up a new wider line mid-corner, but without fully conceding the corner. His car’s body language was saying: “You have the racing line, but you’re not going to squeeze me more than this much, or we’re going to come together”.

There is an obvious parallel here to the story that played out across 1988-1989 at McLaren. True to his reputation, Senna was routinely creating situations where Prost had to back out or risk a racing incident where blame would be shared. Ultimately, Prost was pushed to his limits and decided at Suzuka 1989 it was time to make a point.

I was ahead on points, and I told the team, “There’s no way I’m going to open the door anymore.” I’d done it too often, and I’d had enough. Eventually, we crashed at the chicane. Everyone thinks I did it on purpose, but I didn’t want to finish the race like that. I’d led from the start and I wanted to win. When he tried to pass, I couldn’t believe it because he came from so far back, but I thought, “I’m not going to leave him even a 1-meter gap.” As I’d said, I didn’t open the door. — Alain Prost

Prost was to blame for the accident that occurred. Although Senna came from far back, he was well and truly far enough alongside to own the apex. Senna was moving quickly, but had scrubbed off plenty of speed by the time of the collision and was beginning to rotate his car into the corner. Without the collision, we would likely have seen a move akin to Hamilton’s brilliant overtake on Raikkonen at the 2007 Italian Grand Prix.

Moreover, Prost’s defensive line was peculiar and looked like a last-minute conflicted decision rather than a natural defender’s line. He drifted across the track in the braking zone and was actually steering his car into the grass infield rather than the apex of the corner when contact occurred, as seen from the onboard shot below.

Just as Prost was to blame for the Suzuka 1989 incident itself, Rosberg was unambiguously to blame for the Belgium 2014 incident. Hamilton’s line was not abnormally aggressive and Rosberg was fortunate to avoid a penalty from the stewards, given the poor precedent this may set. However, it’s vital to view both incidents in their full context to understand why they occurred. Neither incident occurred in a vacuum. Both were the result of drivers previously exploiting gray areas in the rules of racing and their teammates then looking to impose clearer boundaries.

[…] de regels moet de aanvallende partij op zijn minst half naast zijn rivaal zitten om zich de bocht toe te […]

[…] a big risk and when it’s better to exercise caution. Baku 2018 was a perfect example. By usual racing guidelines, Ocon was within his rights to close the door on Raikkonen’s speculative move down the […]

thanks for providing this information. i was searching for this for a long. You are doing very good work. Good Luck.

Please also check my work From Team Traffic Racing

Are the rules as explained in section 5 (disputes over the Apex) codified in the official rules somewhere, or is this essentially case law based on steward decisions over the years?

It remains the case that they are not codified for F1, leaving it entirely to the discretion of the stewards on any given race weekend.

Also, nope, the guy overtaking on the outside can not use the full width of the track and hit an apex just because he got half a car ahead. He’s gonna be spun around and blamed too, and rightly so.

I don’t think you get it either. The part where any overlap forces both drivers to keep driving in a straight line is nonsense. The driver nose-ahead can move across, the guy nose-behind has to react.

You see every single race defensive moves being started after the overlap happens, and then the limit is that the move must stop a car’s width away from the edge of the track. You also see every race the move back towards the racing line after a first defensive move happening with an overlap, and the guy outside and behind has to react and move wide too… They don’t just keep driving straight under the illusion they are entitled to do so and cause a crash. Well Mark Webber did in Turkey ’10 but he’ s never been that smart.

Wacky races

HI ! It seems the regulation from 2018 onwards has been significantly “simplified” : the racing section is basically empty now… Any idea why ?

FIA regulations don’t change significatively..

See Apendix L, CHAPTER IV – CODE OF DRIVING CONDUCT ON CIRCUITS

https://www.fia.com/file/103069/download/12831

F1 had it in its regulation, but was redundant.

We have Vettel running Lewis Hamilton onto the grass, 2019 USGP… also see, Lewis Hamilton pass on a harvesting but suddenly & VERY illegally defending Nico Rosberg, Spain GP, 2016.

[…] Kalau nggak mau ngalah, yang disalip yang salah: Mathematical and statistical insights into Formula 1, THE RULES OF RACING […]

7: FIA explain that in 2013:

“According to the FIA’s guidelines, which were made clear to the drivers back in 2013, if a driver is intending to overtake on the outside, and at the apex of the corner he is in front, he must be given room on the exit of the corner”

https://www.autosport.com/f1/news/131590/fia-explains-why-alonso-escaped-spa-penalty

PD: Must analyze someday Vettel’s incidents when racing alongside another car..

Have a bunch of them (last, 3 days ago)

Sorry, commented above. Mistakenly – factually incorrectly, too – thought I was replying to this comment.

Neither the Vettel nor the Rosberg incidents with Hamilton occurred at the apex of a corner.

[…] 60 all-time ranking list, which remains the second most viewed article on this blog, behind only my post explaining the rule of racing. The model I used at that time was fairly simplistic, accounting for only driver performance, team […]

Great article, really appreciated. The 1989 incident though remains controversial and will do forever. Prost clearly steers to the right early to clumsily (he was not used to such tactics) block the other car, but when judging by frozen tv frames one has to consider the car is at speed and drifting to the apex while braking. Moreover he warned before the race he was going to do exactly that, and I have no recollection of Senna or anybody else saying that was not on beforehand. Very simply, nobody thought Prost would be capable of such ‘Senna-like’ behavior and everyone was shocked when it happened, but that doesn’t make him guilty, quite the opposite.

It’s actually easier to tell from the video footage than it is from the still image that Prost was headed inside the apex. Warning that you are going to cause a collision before a race obviously does not make it valid. There are some trivial gaps in logic here.

There are countless examples of Senna creating similar (or worst) situations before and after, with multiple drivers, as correctly referenced a couple of times in the article. No need to enumerate. Senna himself warned of the turn 1 incident in 1990 one day in advance, the difference being ramming another car from behind is definitely, not subjectively, wrong. The trivial point of car drifting to the apex under braking is not addressed in the previous reply, hence still valid.

I am not defending Senna’s moves in other cases, least of all Suzuka 1990. Prost was not drifting to the apex; that was addressed explicitly.

There are some golden rules which you can apply in racing as you need to know rules and regulations of the racing track moreover you need to know how much speed you can control over your car beside this you need to wear helmet always which protects your head.

[…] to the blog F1Metrics […]

Great article, so helpful. Thank you so much!

Your article impresses me. I admire your efforts to share the rules of racing.

[…] August 28, 2014 · by f1metrics · in Crashes, Overtaking, Racing Lines · 96 Comments […]