America loves polls. In the first 26 days of this year, 186 political polls were released. Most of them attracted some attention; some prompted hundreds of headlines. And it’s only going to get worse.

By the time the country prepares to elect its next president in November, the news will be awash with numbers. As a result, some Americans will feel confident they know what the results will be before they have even cast a vote. The question is, should we trust what these polls are telling us? My answer is a reluctant no.

And it’s not just because I was in the UK on election night last year when every single polling company had substantial amounts of egg on their faces. There are five reasons why we should be more distrustful of political polls than ever before.

1. The media are fallible

You may have noticed this: a new poll comes out – often a poll that was commissioned and published by a media company – and it gets heavily publicised by the media. In doing so, the media often increase the name recognition of whichever candidate is in the lead. As a result, that candidate becomes even more well known and gets an extra boost the next time people are surveyed. Donald Trump was polling at 2% before he announced his candidacy. Immediately afterward (while the media was dedicating 20% to 30% of candidacy headlines to one candidate) his support jumped to 11%.

This is known as a feedback loop, and it’s even more important in the early stage of the election cycle when the public is trying to spot someone they know from the throng of white men in similar suits with similar haircuts (did you know there are more than 200 people vying for the Democratic nomination? Can you name any of them whose surnames aren’t Clinton or Sanders?).

2. I’m fallible

Yep – journalists, even statistically literate journalists, can be dumb. It’s the reason why just about everyone failed to predict Trump’s astronomical rise. That’s not just because the methodology of polling is itself flawed (more on that below), it’s also because the analysis is affected by the humans conducting it.

Personal experience and personal beliefs get in the way. Many of the journalists who dismissed Trump with projections that he had a mere 2% chance of winning simply didn’t know any potential Trump supporters in their personal lives – they didn’t get it. And their personal beliefs also encouraged a bit of wishful thinking – they didn’t want to get it.

Until we can find perfectly objective robots to conduct these polls, asking 100% neutral questions and communicating them to you the reader with 100% neutrality, well, we’ve got a polling problem on our hands. Humans, flawed as they are, produce polls that are imperfectly designed, imperfectly conducted and – because of people like me – imperfectly analyzed.

3. Predicting the future is hard

Polls are not a crystal ball but (at best) a decent snapshot of now. Even the wording of polls reflects this focus on the present rather than the future: “If the presidential election were today, for whom would you vote?”

Consider how different your present and future answers would be to questions like: “If you had to eat your lunch now, what would you eat?” or “If you had to choose a romantic partner right now, who would you pick?” You might argue that food, romance and politics aren’t all that similar, but the answers all point to a basic and consistent truth about human preferences: things change.

This is why polls get more accurate as the future draws closer. And even then, there is no opinion poll quite so reliable as the results of what people have actually decided to say in the privacy of a voting booth on election day.

4. It’s hard to contact people

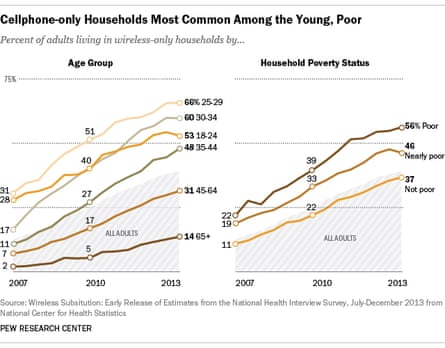

In 2013, 41% of US households had a cellphone but no landline and that number is on the rise. This poses a problem for polling companies because the 1991 Telephone Consumer Protection Act means that they can’t just autodial those cellphones. Not being able to autodial means that it is incredibly expensive and time-consuming for companies to poll those people. Even more problematic, this varies across America – younger households and poorer ones are much less likely to have a landline as seen in the chart below from Pew Research Center. So pollsters need to take that into account when they are trying to take the pulse of the nation.

5. Most people don’t want to be contacted

Response rates (that’s the percentage of people who answer a survey when asked) have plummeted. In the 1930s, it was over 90%; in 2012 it was 9%, and it has continued to decline since then. What’s more, the US population has grown 2.5 times larger since the 30s so the overall participation rate (the percentage of the total population that ends up actually completing a survey) has fallen even faster.

In the end, you’re left with about a thousand adults (if you’re lucky) who are taken to be representative of the approximately 225 million eligible voters in the United States. All of this is well known to pollsters, who claim that their complex mathematical methods can correct for these shortcomings. But rarely have I seen the question asked: “What if a certain type of person answers polls?”

Whether they are cold calling or they have created a panel of individuals that they can repeatedly survey, polling companies all face the same basic issue of how to incentivize people to answer questions.

Some pollsters such as Pew Research Center pay respondents nothing, while others like YouGov offer credits that can be slowly saved up towards gift vouchers. What if the sort of people who are willing to spend hours with little or no reward have something in common? What if they tend to be consistently more conservative? More liberal? Wouldn’t that skew all the poll results in a certain direction? I’ve seen no research on this point, but it certainly seems a potential flaw worth considering.

All of these things together mean that getting a random survey sample that is nationally representative is incredibly difficult. Gone are the days of flicking through a phone book and calling the first number you land on.

And these polling problems aren’t going away, in fact they are only getting worse with time. Since the last US presidential election, polls have failed to predict outcomes of the Israeli national election, the Scottish referendum and the UK general election. In every case, their margin of error wasn’t a few percentage points – it was way off the mark. Most of what I’m saying here isn’t any kind of groundbreaking revelation. So why, then, do we continue to rely on polls?

In a world with so much uncertainty there’s an emotional comfort in the coldness of numbers. We’re reassured when we’re told what will happen. Pamela Meyer, CEO of a deception detection company, often gives the same advice about how to spot a lie: “If you don’t want to be deceived, you have to know: what is it that you’re hungry for?” Journalists need to be more conscious of what they want the polls to tell them before they start reporting them. And readers should be cautious of any headline that confidently tells them what will happen on 8 November 2016.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion