On a rainy Saturday morning in August 2010, Sally Challen left her house in Claygate, Surrey. She had bought the house less than a year earlier, her first step away from a 31-year marriage. That morning, she returned to 1 Ruxley Ridge, just around the corner, her former marital home.

Though she had told few people, Sally, 56, and her husband Richard, 61, were planning to reconcile. They were about to begin clearing the family house so they could put it on the market. The Challens’ home was valued at about £1m, and with this they intended to take an extended trip to Australia, a late-life adventure, before deciding where to live next.

But first Richard wanted bacon and eggs for breakfast, so Sally went out to buy some. When she returned, she felt suspicious, as if Richard had got rid of her for a reason. A quick check of his phone confirmed he’d just had a call from a number Sally knew belonged to Susan Wilce – a woman Richard had met through the networking site Dinner Dates. Sally had Googled Susan’s name the night before. Then she had Googled “Dinner Dates”. Now she asked Richard to explain the call. He replied: “Don’t question me.”

Sally served breakfast and, as Richard ate, she took a hammer and hit him more than 20 times. In case he was still breathing, she stuffed a tea towel into his mouth, before wrapping him in some old curtains. She wrote a note that said “I love you, Sally” and placed it on Richard’s body. Then she washed the dishes and drove back to the home she shared with their son, David.

The next morning, after giving David, then 23, a lift to work, Sally drove to Beachy Head. She parked, called her cousin to confess, then walked to the cliffs. It took a suicide prevention team hours to talk her back from the edge.

Ten months later, Sally stood in the dock of Guildford crown court, looking nothing like the well-coiffed woman she had once been. Her hair was a mess. She had lost a front tooth. Her fingers were nicotine yellow. She barely spoke.

In setting out the murder charge, the prosecution painted a picture of a possessive – or possessed – wife. Wilce gave evidence to explain the call that had made Sally “snap”. Wilce and Richard had arranged to go out on her boat the next day, but Richard called to cancel because of the bad weather; she had called him right back to suggest Sunday lunch instead. According to Wilce, their relationship was “platonic”: Richard was a “lovely man” with a “good sense of humour”.

Sally, the court heard, was obsessive. She checked Richard’s emails, hacked his messages, counted his Viagra. When asked why she had killed him, her explanation was: “I don’t know. I just didn’t think he wanted to be with me.”

At the end of a seven-day trial, she was found guilty of murder. Sentencing Sally to life imprisonment, Judge Christopher Critchlow told her that she had been “eaten up with jealousy” at Richard’s “friendships” with other women. “You are somebody who killed the only man you loved,” he said, “and you will have to live with knowing what you did.”

Now, the case is making headlines again – and events have been cast in a different light. In March this year, Sally Challen won leave to appeal against her conviction, on the grounds that she’d suffered “coercive and controlling behaviour” from her husband – something that did not become a criminal offence until four years after her trial, under the 2015 Serious Crime Act. A date for the appeal is expected later this autumn.

Her lawyer is Harriet Wistrich, who blocked the release of the “black-cab rapist” John Worboys earlier this year. She is also co-founder of Justice for Women, which helped secure the release of Sara Thornton, Emma Humphreys and other women who killed their violent and abusive husbands.

But Sally Challen’s case is a new challenge, the first of its kind. She was not subject to sustained, persistent physical violence. There are no broken bones or hospital visits for Wistrich to draw on. Instead, she has numerous witness statements taken in 2010, but not used in court; emails from Richard to Sally; and months of prison visits and video calls with Sally herself. With this, Wistrich hopes to show that, for 30 years, Richard’s behaviour pushed his wife to the brink. “Here is a woman who absolutely adored her husband – a very old-fashioned housewife who had never committed an act of violence or criminal offence,” Wistrich says.

“From the outside, it’s such a bizarre thing to happen. It’s only when you look at their whole marriage and understand coercive control that the picture starts making sense.”

Is it enough to explain a murderous hammer attack? The Challens’ two sons, David, now 30, and James, 34, believe so. Neighbours, friends and family – as well as Richard’s family and his oldest friend – are all behind the appeal. “That’s pretty unprecedented,” Wistrich says. “Usually in these cases – and I’ve done a lot – you’ve got the family gunning for the woman, saying: ‘She’s killed him, she deserves to rot in jail.’ This time, no one has come out in support of Richard.”

In fact, certain phrases come up repeatedly from those who know Sally. “She wouldn’t hurt a fly.” “She’s very caring.” “If you asked me who – out of everyone I knew – could kill someone, Sally would be bottom of my list.”

So why did she?

Sally Jenney met Richard Challen when she was 15. He was 22. “That’s important to know, to understand what happened later,” their son, David, says. David now lives in London and works for a film distribution company, and is campaigning for his mother. This means liaising with Carolyn Harris, the women and equalities shadow minister (who has visited Sally in prison), and working with Women’s Aid. It also means looking at his family life in the most ugly light imaginable, something he struggles with still (his brother is supportive, but does not campaign publicly).

“I got a real sense, growing up, that Dad was Mum’s childhood sweetheart,” David says. “That romance went on all her life – it seemed very pure. Now I can look at the age gap for what it meant. Mum never had a chance to experience any other relationship or form any adult identity of her own. My dad, and the way he behaved, was all she knew.”

Sally came from a sheltered, old-fashioned family. Her father was Reginald Charles Napier Jenney, a brigadier in the Royal Engineers, who spent most of his life in India. Sally was a “surprise” – her four brothers were teenagers at boarding school when she came along. Her father died when she was six and she was raised by her mother in Surrey, attending school up to O-levels. According to Sally, her mother didn’t think it was “the thing” for a girl to pursue higher education. Her brothers had high-flying careers – one was the auditor general of Hong Kong, another a company director – but for Sally the expectation was secretarial work, husband, children.

Richard Challen lived locally. He was funny, charismatic, making good money dealing cars. His father had been the motoring correspondent for the News of the World and Richard was a petrolhead, passionate about fast cars and Formula One. His oldest schoolfriend, Dellon Blackmore, introduced them when Sally was in her teens. “I’d met Sally on a double date, but I was involved with someone else, so I mentioned her to Richard,” Blackmore says. “She was really beautiful, sweet, kind – she’d do anything for you. Richard took advantage of that.”

In those early years, Sally was devoted and would stop at Richard’s flat after school to clean and cook – but Richard blew hot and cold. There were always other women.

Two events stand out in that early period. One is that Sally became pregnant at 17 and was taken to Harley Street by her brothers for a late-term abortion. Afterwards, they approached Richard, only to be told: “It could have been anybody’s.” The other is the first act of violence recounted by Sally to Wistrich. Sally said she had challenged Richard about seeing another woman, and he had dragged her down the stairs and thrown her out of the front door. (She claims that, for the rest of her life, she hated to confront him in case he did it again.)

And yet she married him. Blackmore was best man at the wedding, which he remembers as a muted affair. “I don’t think her family were too happy, and on the actual day Sally told me that Richard had made her sign a prenup to protect his money. Richard was always very tight – everyone joked about it. But Sally loved him. She was deeply attached.”

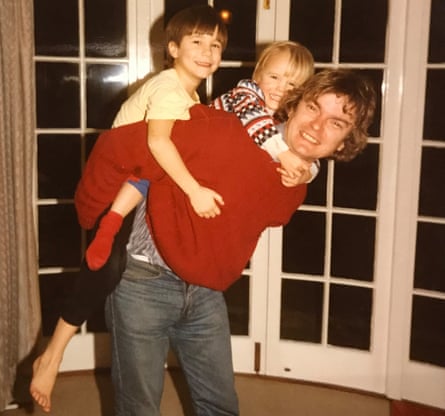

From the outside, the Challens’ marriage looked successful. Richard worked a six-day week and got his own car dealership in Richmond, Surrey. They had two sons and the family settled in 1 Ruxley Ridge. Sally was a dutiful, doting mother, and Richard seemed to James and David a “normal dad”. “I’d always curl up with him on the sofa to watch TV,” David says. “He’d take my brother go-karting and had a little motorbike for me. We had good holidays – Disneyland, Florida; Marbella. For my first 10 years, we seemed normal.”

Others saw it differently. Claygate was a small community. Families got together, held dinner parties, exchanged gossip. Jack Cowdy is one resident whose daughter was the same age as James. Over decades, he got to know the Challens pretty well. “Richard had the cars, the designer clothes – and was very much a man’s man,” Cowdy says. “He’d criticise Sally in front of everyone – ‘My God, you’ve got a big arse!’ – and try to get you on his side.”

Richard flouted normal codes. In 1991, his motorbike was chased by police helicopters for excessive speeding, but in court, police couldn’t prove he was riding it. In 2006, he was back in court: he’d crashed his Ferrari on a race track in Belgium, then shipped it home and claimed on his insurance, inventing a story about being hit by a lorry in Claygate. He was found guilty of fraud and received a 51-week suspended sentence.

“There were so many odd incidents,” Cowdy says. For two years running, Richard sent out Christmas cards that showed him leaning on a bonnet straddled by nude or topless women. “He wasn’t well liked – my wife would say he was sleazy,” Cowdy says. “If you were having a dinner party and people knew Richard and Sally were coming, you wouldn’t get 100% attendance.”

At home, as the boys grew up, they also became aware of problems. “My mum was the hub, the main gear. She did everything at home and also all the admin for Dad’s business,” David says. “When I was 13, she got an office job with the Police Federation, and from then on all the household expenses had to come from her income. Dad bought himself a Ferrari, a Cartier watch, he went to grand prix events. It was as if he’d decided to do his own thing. He once asked why I wasn’t in school – in the middle of the summer holiday.

“Mum was loving, kind, calm, accepting, everything you’d want in a mother. She’d always listen. When I realised I was gay, it was Mum who talked to me. There was an unspoken agreement not to mention it to Dad.”

Both sons remember Richard’s constant insults and petty rules. “‘Thunder thighs’ was a phrase we heard a lot about Mum,” David says. “And if someone complimented her, Dad would say: ‘You haven’t seen her without clothes.’”

“The atmosphere changed when my father got home from work,” James says. “Everyone was on edge. Dinner was generally uncomfortable, because of arguments over whether my mother had cooked something to his liking.

“If he was watching TV and we were talking, he’d just turn the volume up – and we weren’t allowed to use the TV when he wasn’t there, because it would ‘waste its limited lifespan’.” (Sally’s friends say that Richard sometimes locked up the phones when he was out, as he paid the bill.)

Wistrich is most shocked by how “incredibly old-fashioned” the marriage was. “I’ve seen a lot of domestic violence relationships, but I didn’t think marriages like this still existed,” she says. “Everything was about servicing Richard.” According to Sally, the couple’s sex life consisted of whatever Richard enjoyed, when he wanted it. Sally would be sent upstairs to get ready, because he didn’t like to see her naked – and she had to wash first, because Richard claimed she smelled. (This so concerned Sally, she once consulted a doctor, who assured her she didn’t.)

Richard openly pursued other women. He had several mobile phones on the go – after his death, more were found in the spare tyre of his car. On one occasion, Sally followed him and saw him enter a “massage parlour” yards from where she worked. Shortly afterwards, a police raid on the local news revealed it was staffed by trafficked women.

But Richard was unrepentant. That, David says, was the hardest part. “Dad would lie and deny and tell Mum she was mad or drinking too much. As James and I got older, we challenged him, too – especially about the brothel. But it was like Teflon. Dad didn’t feel he needed to answer the questions.”

Where was Sally in all this? Records show that she often saw her GP about sleeplessness, low appetite, early waking and “domestic stress”. At social gatherings, she became known as someone who drank and smoked too much, and talked incessantly.

“And there was only one thing she talked about, and that was Richard,” says one of Sally’s friends, Sarah Goodwin. “It was endless. For all the years I knew Sally, she was besotted with him, absolutely desperately in love. She didn’t want to anger or upset him; she just wanted to be loved by him. And from the outside, you could tell that wasn’t going to happen.”

Sally was also strangely isolated. Some people avoided the couple, and Richard had never approved of Sally seeing friends alone. (Goodwin was accepted only because Richard had become a friend of her husband first, after they met at a car rally; also, she lived far away in Scotland.)

Richard would break a friendship at a moment’s notice, as he did with Dellon Blackmore. Although his oldest friend had married and moved to Los Angeles, the couples saw each other several times a year. In the late 90s, the Challens visited. “One evening, James and David had gone to bed, my wife and Richard had gone up, too, so Sally and I were the last to leave. We stood up and I gave her a hug and goodnight kiss – I hug her every time I see her, and have done for years – and Richard walked in. He said: ‘What’s going on?’ My response was: ‘Are you kidding?’ The whole thing was absolutely stupid, much ado about nothing, but after that holiday, I wrote and called, but Richard never responded.” Sally later told Wistrich that, on that night, Richard took her upstairs and raped her.

When coercive control was added to the statute books, it recognised something that victims of domestic violence had been explaining for decades: that the physical assaults were “not the worst of it”. It was the pattern of isolation, humiliation and domination that had broken them down, and robbed them of their lives.

It’s a hard area to police, or even put on paper, because it happens slowly, subtly and covers a range of possible behaviours. It’s also deeply personal, explains Davina James Hanman, an independent Violence Against Women consultant. “The perpetrator has intimate knowledge of the victim, so the patterns of abuse and control are specifically tailored,” she says.

Hanman wrote the report that Wistrich submitted in support of the appeal, and identified common control tactics used by Richard. “Gaslighting”, or causing Sally to question her sanity. “Compliance humiliation”: imposing petty rules to humiliate her. Isolation. Constant criticism. Emotional abuse. “Richard put Sally in that weird space of feeling absolutely and utterly worthless, and yet more and more attached to him,” Hanman says.

Richard’s own family attest to this. His only brother emigrated to Australia years ago and has since died; his wife, Trish, recalls that Sally and Richard visited together for a family wedding, where Richard caused much embarrassment by attempting to dance with only the younger female guests. “It became apparent that their marriage was in trouble and Sally was suffering,” Trish says. “That was the first time Sally spoke about their relationship, saying: ‘If I ever left Richard, he would make my life hell.’ In hindsight, we regret not being able to support our UK family, despite the distance.”

Finally, in November 2009, Sally managed to break away. At the time, she told Goodwin that seeing the brothel raid on TV pushed her to leave. Using inherited money, she bought a small house, taking David, then 22, with her. (James, 25 at the time, had moved out to live with his girlfriend.)

Without Richard, Sally struggled. “She was always on the phone,” Goodwin says, “telling me she was utterly miserable. She didn’t know what to do with herself, because Richard wasn’t there to tell her. Richard had been her life, and without him, she didn’t seem to have one. I repeated that she was doing the right thing, that she had to give it time.”

Instead, Sally asked Richard to take her back. He responded with an email, which Wistrich has seen: “I will consider your return only on these terms. You will continue and complete the divorce only with a £200,000 settlement.” This was far less than she would have been entitled to after a 31-year marriage. “That when we go out together, it means together. This constant talking to strangers is rude and inconsiderate. We will agree to items in the home together. To give up smoking. To give up your constant interruptions when I am speaking.”

Sally desperately wanted the reconciliation – and as the two began seeing each other again, Richard suggested a new start in Australia. But she also feared this was a trick, that he was seeing other women and offering these “terms” in order to walk away with most of their money. Her divorce lawyer confirms that she stopped and started divorce proceedings 13 times during the “separation”. She was back in “checking mode”, hacking Richard’s phone, reading his messages.

“In the fortnight before Dad was killed, Mum’s behaviour was odd,” David says. He had known nothing of the reconciliation, but suspected they were back in contact. “She was distracted, unfocused, she wouldn’t listen. After years of being pushed around and played with, it was as if a ball was rolling. When I found out what she’d done, I didn’t even think to ask her why.”

The 2011 trial was a disaster for Sally Challen. Her defence team, who have declined to speak to the Guardian, chose not to use a provocation defence that could have reduced the murder charge to manslaughter. In statements made at the time by Cowdy, Goodwin, James Challen and others, the word “control” comes up repeatedly, but in 2011 this wasn’t a red flag. “Outside the specialists working in the field, domestic violence was seen as physical – black eyes and broken bones,” Wistrich says.

Instead, the plea was diminished responsibility, using Sally’s medical history and evidence from a psychiatrist who had diagnosed depression. “On one level, it makes sense, because Sally was clearly not in her right mind,” Wistrich says. “But the prosecution’s psychiatrist disputed the diagnosis.”

Richard’s behaviour was barely raised. Cowdy attended the trial and asked the QC why they weren’t looking more closely at the marriage. “His reply was: ‘Let’s not go there’,” Cowdy says. “Sally’s brothers asked the same question. The defence seemed to feel that attacking the murder victim might reflect badly on Sally. I don’t think the jury had any idea of the extent of his behaviour.”

Sally is now 64 and seven years into an 18-year sentence. If her appeal fails, she will be 75 when she’s due for parole. “My mum will not harm another person,” David says. “If she wins, there’ll be time for her to have a life. She’ll see the boys she helped grow into men, and hopefully grandchildren, too. It’ll be tough,” he adds, “as Dad isn’t here any more, and she still says she loves him. People find that hard to believe.”

Including her lawyer. “The thing I’ve struggled with when I’ve talked to Sally is that she has said all along: ‘I still love him and I miss him so much,’” Wistrich says. Perhaps this more than anything shows how complete Richard Challen’s hold was. Not one family member, friend or neighbour I spoke to had anything positive to say about him. It seems the only person grieving him is his devoted wife – serving life for his murder.