The fire service played “no meaningful role” in the aftermath of the Manchester Arena bombing because they arrived two hours late, a review of the response to the attack has found.

Although two fire crews were stationed close enough to the Arena to hear the explosion, they were sent to a rendezvous point three miles away amid fears that there was a marauding terror attack and they would not be safe, the review concluded.

When they eventually arrived at the Arena, more than two hours after Salman Abedi detonated his suicide bomb on Monday 22 May 2017, the visibly frustrated fire officers were not immediately allowed on to the concourse to help because of communication errors between “risk-averse” officers in charge.

Dawn Docx, the interim chief fire officer of Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service (GMFRS) said she apologised unreservedly for the failures in the previous leadership of the service at the time of last May’s outrage.

“It is clear that our response fell far short of what the people of Greater Manchester can expect,” she told a press conference following the publication of a report by Lord Bob Kerslake into the emergency response to the attack.

Quick GuideManchester Arena bombing report: the key points

Show

• The Greater Manchester fire and rescue service did not arrive at the scene and therefore played “no meaningful role” in the response to the attack for nearly two hours.

• A “catastrophic failure” by Vodafone seriously hampered the set-up of a casualty bureau to collate information on the missing and injured, causing significant distress to families as they searched for loved ones and overwhelming call handlers at Greater Manchester police.

• Complaints about the media include photographers who took pictures of bereaved relatives through a window as the death of their loved ones was being confirmed, and a reporter who passed biscuit tin up to a hospital ward containing a note offering £2,000 for information about the injured.

• A shortage of stretchers and first aid kits led to casualties being carried out of the Arena on advertising boards and railings.

• Armed police patrolling the building dropped off their own first aid kits as they secured the area.

• Children affected by the attack had to wait eight months for mental health support.

The fire service decided to send in units only after a senior officer overheard a conversation at 00.15 on Tuesday in which he learned armed police had been deployed an hour and a half earlier to check the incident was not a marauding terror attack of the type seen in Paris. Fire officers later told Kerslake’s reviewers that had they been told this key information by police earlier they would have potentially sent in special rescue teams sooner, knowing the scene was likely to be secure.

Vodafone also comes in for heavy criticism in the review.

The phone company operates an emergency phone system that should kick in following a terror attack, allowing other police forces to help call handlers in Greater Manchester. It should also allow the local force to set up a casualty bureau to coordinate information about the missing and injured.

But the National Mutual Aid Telephony system operated by Vodafone experienced a “catastrophic failure”, Kerslake found. This caused significant stress and upset on the night to the families involved, who were “reduced to a frantic search around the hospitals of Greater Manchester to find out more”.

Vodafone, which has held the Home Office contract to provide the service since 2009, must give urgent guarantees that it does not happen again and put tested back-up systems in place, said Kerslake.

Greater Manchester fire and rescue service (GMFRS) and the north-west fire control both accept they “let down the people of Greater Manchester and other visitors to the city that night”, said Kerslake. The local fire service has three special response teams equipped with “Sked” stretchers intended for the rapid extraction of casualties from a terror attack. But the teams were never deployed and casualties were instead carried out by Arena staff on advertising boards and railings.

Some casualties complained they lay injured for two hours while the fire service waited for orders three miles away: despite GMFRS being the first and only fire and rescue service in England to have trained and equipped all its firefighters and pumps to respond to cardiac arrests for the ambulance service.

The independent, 226-page report was commissioned by Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, after he was contacted by disgruntled fire officers desperate to deploy but who were left to watch the response unfold on TV. Burnham said the fire service followed protocol too rigidly:

“As this report repeatedly makes clear, there is a danger of inflexibility in applying a theoretical response rather than responding to the unique reality every incident poses. This can lead frontline responders to make judgements that might be right on paper but wrong in practice and this in part explains the fire service’s mistakes,” he said on Tuesday. He called ont he government and home office to ensure that any protocols provide “sufficient flexibility to respond to the different circumstances.”

The then £155,000-a-year chief fire officer, Peter O’Reilly, has now retired, keeping his pension with no action taken against him.

Asked if any officers had been disciplined for their handling of events, Docx said: “We are very much a learning organisation. We are not seeking to go down a discipline route.”

Andy Burnham said no one individual should bear all the responsibility for failures and no one should be “scapegoated”.

Kerslake concludes that had GMFRS assets been deployed immediately then firefighters would have been much better placed to support and, potentially, to accelerate the evacuation of casualties from the foyer. The failure by fire chiefs as “extraordinary” and “incredible”, he told reporters. But he insisted he was not able to determine whether quicker deployment of firefighters could have saved lives. That will be for coroners’ inquests to decide.

In contrast, he said the actions of the arena staff, British Transport Police (BTP) and members of the public who stayed to help showed “enormous bravery and compassion”. Police and ambulance personnel were also very rapidly on the scene and there followed “a remarkably fast deployment of armed officers” to secure the area and paramedics to attend to the wounded.

As well as representatives from the emergency services, the council and the Arena, 200 members of the public affected by the attack on 22 May were interviewed by Kerslake’s team, including family and friends of 11 of the 22 people who died.

Many complained about being “hounded” and “bombarded” by the media. Some said photographers took “sneaky” pictures through a window when they were being told their loved ones had died.

At one hospital, a reporter sent a tin of biscuits for staff containing a note offering £2,000 for information. Several people told of the physical presence of crews outside their homes. One mentioned the forceful attempt by a reporter to gain access through their front door by ramming a foot in the doorway.

The child of one family was given condolences on the doorstep before official notification of the death of her mother. Another family told how their child was stopped by journalists while making their way to school.

There were at least two examples of impersonation, said Kerslake. One respondent said they talked to someone pretending to be a bereavement nurse; another said journalists phoned the hospital pretending to be from the police.

“To have experienced such intrusive and overbearing behaviour at a time of such enormous vulnerability seemed to us to be completely and utterly unacceptable,” Kerslake writes. He asks the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso) to review the operation of its code and consider developing a new code specifically to cover similar events in future.

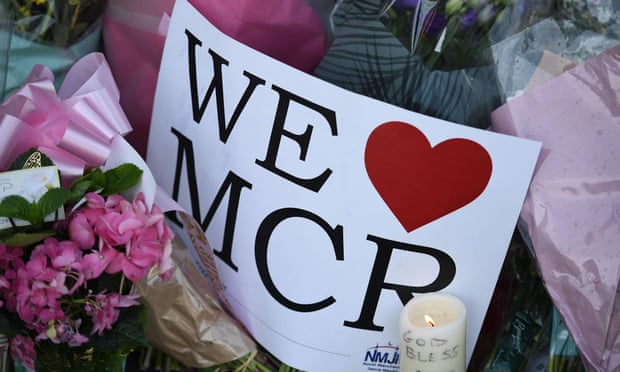

While some families were grateful to have received money from the We Love Manchester emergency fund, which raised £20m from members of the public, others were angry. Some objected to the awards being made public. “We weren’t happy ... that every member of the country now knows what’s in our bank account,” said one. Others complained that bereaved relatives received more than those who survived with horrific injuries.

Some reserved their ire for the government: “My family feel very angry and let down by the government as there has been no help, support or funding in any way ... if it wasn’t for the generosity of the public ... we would probably be homeless.”