His hand slaps down on the sketchpad. "Don't read that," says Andrew Davenport, refusing to move his fingers, despite my cajoling. "It's terrible." His hand is covering a short rhyme, written in pencil, that was his very first attempt to devise a song for a shapely piece of blue fluff called Iggle Piggle, who first came to life on these sketchpads three years ago, and who has since all but taken over the world.

I'm astonished to find Davenport so unwilling to let me see the rhyme. It's not as if his reputation as the king of kids' TV isn't assured. As well as being the co-creator of Teletubbies, which in its 13 years has travelled to 120 countries and generated £2bn, Davenport is the man behind In the Night Garden, the gently surreal bedtime show for pre-schoolers of which Iggle Piggle is the star. In the Night Garden – which first aired on the BBC in 2007 and features engagingly colourful characters who meet, play, sing, wander about, then tuck up for bed – may even eclipse Teletubbies: it has already conquered 35 countries and territories, from Norway to China, where book sales have reached 1.5m. More importantly, for at least a year, the show was pivotal in getting my own daughter, now three, off to bed. As far as I'm concerned, Davenport is bigger than Santa.

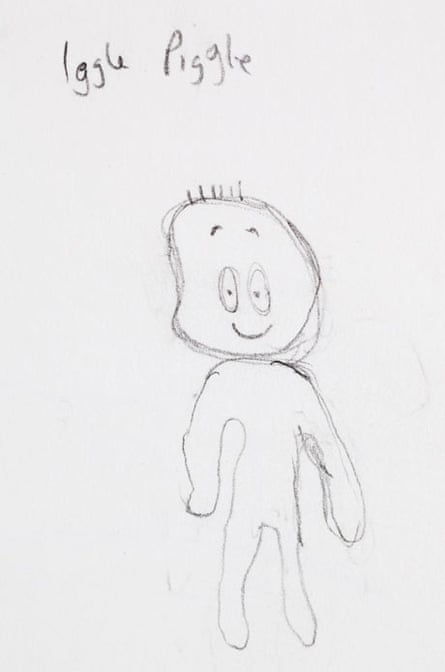

We turn the page. "This is the first ever drawing of Iggle Piggle," says Davenport, who is opening up his prized sketchbooks to an outsider for the very first time. The Guardian's photographer, also the father of a toddler, and I both gasp. Davenport points to the figure's floppy, bean-like head. "That head shape was the main feature. It became characteristic. With a drawing, you can create reality immediately. Character almost forms itself: you can switch off your editorial mind. In the Night Garden all started from this sketch. He's a sort of a lost toy, a floppy character who has made his way through the world somehow."

Iggle Piggle is now making his way through the world all the way to the stage: the In the Night Garden Live show opened in Liverpool last month and has just arrived in London, before heading for Glasgow and Birmingham. "For a long time, I didn't want to do a stage show," says Davenport. "It's difficult to create something that works for a theatre audience in the way that a TV show works for one. And conventional theatres are simply not designed for two-year-olds, with those seats they can't see over."

The solution takes the form of a travelling inflatable theatre fitted with baby-friendly touches, such as microwaves for the warming of milk (promising a whole new kind of interval drinks bedlam). Audiences are offered a choice of two stories. "One features Iggle Piggle losing his blanket," says Davenport. "The other features Makka Pakka washing everyone's faces." Neither story, it's safe to say, will come as a great surprise to regular viewers of the show, many of whom are parents who find its soothing antics easier on the eye and the ear, not to mention the imagination, than Teletubbies.

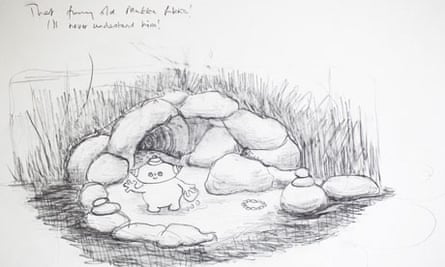

We flip to the first ever sketch of Makka Pakka, outside his cave, dripping sponge in hand. Where did the idea for this bear-like, pint-sized wiper of faces come from? "Often, children don't like having their faces washed," says Davenport. "If you can make a playful version of that, it will defuse the situation, if you like. I thought it was quite funny to have him just come on with a trumpet and interrupt the whole narrative – to make everyone stop and have their faces washed. It seemed quite truthful for a child."

Davenport, 45, has no children of his own, but a godson, he says proudly, "has lived through In the Night Garden". Tall and slim, with cropped hair and a quick laugh, he wears a dark blue shirt and looks as smart and spotless as his studio in London's East End. At his desk sits a keyboard and a phone – he sings into its answering machine if he thinks of a tune while he's out; a piece of software turns it into music.

Shelves bear the sort of books you might expect: A History of Toys by Antonia Fraser, and Seeing Things by Oliver Postgate, Davenport's hero and the creator of his own favourite kids' TV show The Clangers. "Who wouldn't want to live underground on a separate planet?" he says with relish. "It's a totally alien world that's just fantastic." Some titles are, however, a little more cerebral: The Developing Child by Bee Boyd, The Language and Thought of the Child by Jean Piaget.

He quotes Piaget when I ask him to explain the phenomenal success of In the Night Garden, and how it manages to be both soporific and entertaining. "I'm not sure soporific is the right word," he says, pointing out that the show finds very young children just as their play is expanding out of the mere physical (bang it, chuck it, break it) and into the world of ideas. "Piaget had this notion of operational play and symbolic play. Up to a certain age, a child will take hold of a doll and bang it to see what it sounds like. Then, at a certain point, that doll becomes symbolic. It starts to stand for a person. It's that kind of play In the Night Garden is accessing. And it's that, I think, that is so calming."

Before setting off to meet Davenport, I'd asked my daughter if she had a question for Iggle Piggle's daddy. "Why does Iggle Piggle have to go to bed?" she said. "That's a really interesting question," says Davenport. "He's the connection for the child, the one who goes to sleep at the beginning and enters the Night Garden. But he's also, crucially, the only character not in bed at the end. 'Somebody's not in bed – Iggle Piggle's not in bed.'

"Bedtime really commands a child's entire day. Very often children don't have a proper sense of time. They live with the idea that, at any moment, someone could just take them from what they are doing and send them to bed. It can be a difficult moment: being suddenly alone. So In the Night Garden makes a metaphorical explanation for sleep, which is one of the only things in a child's life it can't be accompanied on. That's why you have the image of Iggle Piggle alone on a boat at the start, floating on a dark swelling ocean that's a metaphor for sleep."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion