The numbers and statistics that can be pulled from the great Sugar Ray Robinson’s record are truly extraordinary. A rapid and exemplary 85 and 0 amateur career preceded exactly 200 professional bouts, spread thick and heavy across a full quarter of a century. In that time he took on all-comers, from 129lb featherweights to 173lb light heavyweights, with the calibre of Hall of Fame fighters such as Kid Gavilian, Carmen Basilio and Gene Fullmer sandwiched in between.

He was victorious on 173 occasions, scored 108 knockouts, and no man was able to knock him out. Only the immeasurable power of the sun in a sweltering Yankee Stadium achieved that feat. Robinson spent 13 rounds schooling the bemused 175lb champion, Joey Maxim, before collapsing with heat exhaustion and failing to answer the bell for the next round. Even then, Robinson was reluctant to concede that a celestial body as meagre as the centre of our solar system could have overwhelmed him.

In the dressing room after that fight in 1952, a barely coherent Robinson looked to Mayor Impellitteri of New York, a trio of medical doctors, and his manager, George Gainford, for some clarity on what had just happened. “He didn’t knock me out, did he?” Robinson mumbled as Gainford and Impellitteri supported his semi-listless body while it lolled towards the sanctuary of a cold shower. The two suited men assured Ray that it was the eviscerating heat, not Maxim, that had prevailed but Robinson, now 16 pounds lighter than at the opening bell, was not convinced.

As the cooling water began to take effect, he spoke more clearly. “The heat didn’t beat me,” he began, shaking his head. “God willed it that way. It was God. He wanted me to lose.” Even the magisterial Robinson could not expect to compete against such an opponent.

His other great foe was a slightly less saintly figure with whom he shared six fights. The name Jake La Motta is the most populous on Robinson’s hit-list, yet it is conspicuous by its absence from Ray’s knockout tally. The two men were destined to be inextricably linked from the moment they first toed the line opposite one another in Madison Square Garden in 1942.

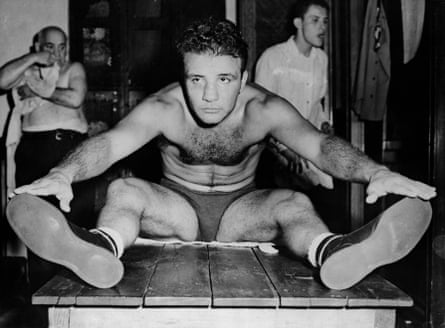

The 35 and 0 Robinson was already on the road to welterweight immortality when he accepted the challenge of facing a 160 pounder who, while not yet a marquee fighter, was regarded as one of the toughest men to ever lace a glove. A later autobiography, for which the term brutally honest could have been coined, appended the prefix Raging to his nickname, but at the outset he was simply the Bull, or the Bronx Bull, on account of a fighting style that resembled a hungry front row hooker on the rugby pitch, ferociously boring into a busy ruck in search of the ball.

He was a one-man riot, a crouching, bobbing, hooking menace who appeared to thrive on the punishment he absorbed in every round he fought. Some brawlers are happy to take one to land one. La Motta gladly accepted 10 in return. This was a guy who, when asked to describe his childhood, said that growing up is having bad things happen to you for no reason. He was bred not to give a fuck. A confession later in his life says it all: “I took unnecessary punishment when I was fighting. Subconsciously – I didn’t know it then – I fought like I didn’t deserve to live.”

He was as blunt and crude as Robinson was cute and slick. The two men shared a profession but their philosophies on how best to do their jobs were at polar opposites of the pugilism spectrum. Robinson believed boxing was about finding out who was the smartest in the ring, while La Motta was convinced it was a contest to see who was the toughest. It was an ideological clash that blessed us with an enduring rivalry and guaranteed an everlasting legacy.

Robinson comfortably won their first encounter in a unanimous 10-round decision in front of almost 13,000 in the Garden. The Associated Press report described a “willing and rugged workman” being “completely outclassed” by a “skinny negro swatter.” The United Press, meanwhile, was less flattering in claiming that the “slender, dancing 21-year-old negro” deserved little credit for beating the “human truck” La Motta while “back-pedalling.”

Whichever way you choose to analyse the two contrasting styles, the template for the rivalry was set in stone. La Motta was the bull and Robinson was the matador. The squat, rugged La Motta was going to brawl with furious energy and the lithe, elegant, Robinson would swerve and shimmy and toy with his opponent, torturing him until his spirit was broken and his body open to a decisive estocada.

For some boxing fans – the United Press reporter included – the absence of that final, bloody stage of the contest renders the impressive beauty of the performance almost irrelevant. Boxing, like bull-fighting, is a blood sport and people who never enter the ring are often quick to call for a violent end to proceedings: an easy demand to make from the behind the safety of the ropes.

In early 1943, most of Europe and South East Asia was on fire as the battles of the second world war grew deadlier and ever more entrenched. A childhood mastoid operation for La Motta – the result of a violent father yanking on his left ear as an over-zealous dog trainer might on a misbehaving pit bull’s leash – made La Motta exempt from military service. But Robinson was practically perfect as a physical specimen and his induction into the US Army was set for 27 February.

With the standard private’s $50-a-month wage unlikely to sustain Robinson’s taste for the good life, he was happy for Mike Jacobs, the most powerful figure in boxing at the time, to hastily secure a few paydays before his war duties took precedence. Jacobs delivered and in February 1943 Robinson fought an astonishing 30 rounds across three fights in just three weeks. First up was a rematch with La Motta in front of 19,000 fans in Detroit’s Olympia Stadium.

Since their first meeting, in 1942, they had both fought and won five times. La Motta was hardly a choirboy between fights, but Robinson, whose roving eye for women was as quick and instinctive as his fists in the ring, was particularly distracted over that particular holiday period. Though he knew he’d never be close to the front line, perhaps the spectre of his looming army induction subconsciously sent his psyche into last hurrah mode.

Whatever the reason, he was not ready for La Motta that night and, in Robinson’s own words, the Bull stomped him for the full 10 rounds. In the death throes of the eighth, a right hand to Robinson’s mid-section and a left to his jaw knocked him through the ropes and out of the ring. He scrambled back to listen to a count that reached nine before the bell provided some respite. Robinson survived until the end but there was no surprise when La Motta was awarded the unanimous decision and the honour of being the first man to defeat Robinson. That achievement alone was enough for the Bull to be named Ring Magazine Fighter of the Year.

Robinson was distraught but the emotional pain was eased somewhat by the knowledge he could right the wrong in three short weeks. Incredibly, he fought again before that against California Jackie Wilson, a US Army sergeant on leave and a 47-4-2 boxer. One of Wilson’s four defeats was at the hands of the Bronx Bull just a month before when he entered the ring as a 4-1 favourite and left it 10 rounds later, in La Motta’s words, “a sadder but wiser man”. Robinson beat him too but it was a tough outing and one judge scored the fight a draw.

A week later he was back in the Garden for a third fight with La Motta. Announced as Sugar Ray Robinson, he knew that the following morning in the Manhattan Island induction centre, he’d be called forward as Private Walker Smith Junior.

To this day, La Motta maintains he won Part III and believes the judges were blinded by the shine that emanates from a public figure answering his country’s military call. He backs up his claim by pointing to the seventh-round knockdown and subsequent eight count that Robinson had to endure. But in truth, few saw it as the Bull did.

After the folly of engaging with La Motta on his rugged terms 21 days before, Robinson played to his own strengths this time around, keeping the Bull at bay on the end of a long, spiteful jab. Whenever La Motta did manage to get past that left hand, Robinson adroitly conjured up enough space to welcome his opponent inside with fierce uppercuts. The referee gave La Motta three rounds but neither ringside scorer could find more than two that ended in his favour. The decision was unanimous.

Their fourth meeting, back in the Garden two years later, was almost identical as Robinson controlled the fight behind his quicksilver jab, only allowing La Motta isolated success in the sixth round when he temporarily took his foot off the gas.

The Bull had more success in their fifth bout, six months later in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, and the first to be scheduled for 12 rounds. La Motta figured the extension benefitted him most as Robinson tended to start fast and then coast to victory towards the end. He may have been right, and one judge saw La Motta as a clear winner this time, but ultimately he was on the wrong side of a split decision. It would be a long six-year wait before he had another shot at Robinson.

During that time La Motta established himself in many observer’s eyes as the premium middleweight in the world. Unfortunately that counted for little in the 1940s if you were not prepared to play ball with the likes of Blinky Palermo and Frankie Carbo. La Motta was nothing if not his own man and he took a natural dislike to the wise guys seeking to control boxing for their own means. For years he rebuffed their advances, to the point that the hard-headedness that made him such a formidable boxer looked like it would prevent him from getting his mitts on the top prize. He looked on from the sidelines enviously as Tony Zale, his childhood Bronx pal Rocky Graziano, and Marcel Cerdan continued to share the title among themselves.

Finally, in 1947, he cracked and threw a light heavyweight bout against Billy Fox in almost farcical circumstances. It was just one of the many dives the mafia manufactured in those days but this one was so blatant that the Boxing Commission felt obliged to act. Seizing upon a ruptured spleen that La Motta’s physician, Dr Nick Salerno, confirmed his patient suffered in training, they suspended La Motta for seven months on the grounds of concealing an injury and fined him $1,000.

The time off was tough for La Motta but the fine was peanuts, especially considering he had already paid the mob $20,000 as part of the deal to secure a shot at Cerdan’s middleweight crown in June 1949. He seized his chance and forced a stoppage of the great Frenchman, who survived nine agonising rounds one-armed after sustaining a shoulder injury following a knockdown in the first. Papers were signed for an immediate rematch but Cerdan’s plane tragically crashed in the Azores en route to taking the middleweight to watch his lover, Edith Piaf, in concert in New York.

Instead, La Motta fought and lost to Cerdan’s countryman, Robert Villemain, in a non-title bout before five outings in 1950 that culminated in his stoppage of Laurent Dauthuille. He had been well behind on the scorecards before landing the knockout punch with just 13 seconds to spare. “Of such extraordinary doings are champions made,” was Ed Sullivan’s legendary summary of the performance.

It wasn’t just La Motta who tangled with the mob, however. Organised crime’s control over boxing was at its most complete during the 1940s and every fighter who could be of any value to the mafia expected a visit from a mobster in a sharp suit sooner or later.

Like La Motta, Robinson rebuffed offers he shouldn’t have been able to refuse. And, like La Motta, the decision to go it alone delayed his official coronation as a world champion for years. In fact, it wasn’t until Robinson’s 76th fight – and 74th win – against Tommy Bell in December 1946 that he finally got his hands on the 147lb belt.

He defended it successfully, though sparingly, for the next five years but in truth his body was by now naturally maturing into the physique of a middleweight and, when the sixth La Motta fight was signed, Robinson vacated his welterweight title and focused on the 160 pounders.

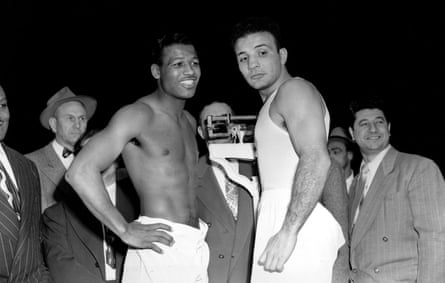

La Motta may have been the 160lb champion of the world, but save for the precise moment he weighed in on that limit, he was never anywhere near the weight. A year before the final Robinson bout he fought the light heavyweight, Dick Wagner, and registered at 170lbs. Four months after his last dance with Robinson, he weighed in to face Bob Murphy at 175lbs.

Many believed La Motta had the advantage over Robinson by being the naturally bulkier man at middleweight, but the reality was he was so much bigger that the effort and sacrifice needed to make weight was a major disadvantage. He struggled to do it for the first meeting in 1942 so the torture to hit 160lbs nine years later when he’d walk about the street close to 190 was almost unbearable.

In his autobiography La Motta talks openly about his weight issues and divulges a phobia of steam rooms born from having spent so many tortuous hours trapped in their humid, porcelain confines, frantically trying to sweat off the excess ounces as the seconds tick away. He speaks of days when he was lucky to be allowed a lick of an ice cube to keep him going and estimates that throughout his career he cut a total of 4,000lbs in weight.

Boxers weighed in on the day of the fight back then, normally at noon. Anticipating his weight woes, however, La Motta had stipulated that for this one, they’d do it at 10am. The idea was to afford the Bull an extra couple of hours to eat and drink and generally build up the strength he so desperately needed before facing the best boxer on the planet.

The strategy would have been sound in normal circumstances, but so extreme was the journey to an 160lb catabolic state that, when it reached its destination, La Motta’s body was effectively under attack by the symptoms of starvation. He was surrounded by all the beef broth and rare steak a red-blooded male could handle but his shrunken stomach and ravaged appetite would not allow him more than a few paltry mouthfuls. Understandably perturbed, his response was classic La Motta: he sent his long-suffering brother Joey to fetch a bottle of brandy.

Robinson, on the other hand, tended to stay well clear of alcohol: he’d seen the damage it could do while growing up under two parents with a weakness for the hard stuff. But he was not without his own idiosyncrasies when it came to pre-fight fluids, particularly if they afforded him the chance to gain a psychological edge over an opponent.

A tall glass of cold, fresh beef’s blood was Robinson’s tipple of choice and in the build up to his final fight with La Motta, he spooked the Bull by ordering a glass at a contract-signing luncheon. La Motta looked on in disbelief as Sugar nonchalantly seasoning his beverage with salt and pepper.

“You’re outta your mind!” he snorted when Robinson offered him a taste.

“Don’t you know that the great Joe Louis drinks eight ounces of blood every day for three weeks before a fight? It gives you strength for the last kick,” Robinson replied, now fully warmed to his task of getting inside La Motta’s tough nut of a head.

“Keep it.” Was La Motta’s succinct response, but Robinson knew he had him.

“All right,” he smiled, raising the glass as if to toast victory. “When I’m still dancing in the last round and you’re dragging, you’ll know why.”

In truth, however, Robinson was not planning to let this fight get to the last round. A visit from the boxing underworld as he relaxed at his Pompton Lakes training camp in New Jersey had convinced him that he couldn’t afford to risk bringing the judges into play this time. The infamous Mr Gray, otherwise known as the Murder Inc. hitman Frankie Carbo, had pulled up in his big, black Buick Sedan one chilly Sunday morning and decided to try his luck leaning on Robinson in person.

“I represent the Bull,” he said from underneath his ubiquitous grey fedora. “I got a deal for us.”

“What kind of deal?” Robinson answered warily.

“I want you and the Bull to have three title fights,” Carbo continued. “You’ll win the first. He wins the second. The third is on the level.”

“You mean I take a dive in the second?” Robinson fired back with disgust. “You got the wrong guy.”

“Three fights is a lot of money,” proffered the wise guy.

Ignoring the temptation, Robinson turned his back on Carbo but not before delivering a message for La Motta.

“You tell the Bull to keep his hands up and his ass off the floor.”

That was the last Robinson heard from Carbo until 1966 when they bumped into each other in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The boxer was putting on an exhibition and the crook was serving 25 years for conspiracy and extortion against a welterweight champ by the name of Don Jordan. “Say hello to the Bull for me,” were Carbo’s departing words.

Given the duration of their love affair, it was fitting that their sixth and final bout took place on 14 February, Valentine’s night. “We met so many times we almost got married,” said La Motta in later life as a cabaret club entertainer and, indeed, Robinson was La Motta’s best man the sixth time the Bull hurtled down the aisle. A variation of the joke ran that, having fought sweet Sugar Ray so many times, it’s a wonder La Motta didn’t contract diabetes.

They were not friends yet, however, and when the first bell rang in Chicago Stadium, the two men did not waste any time in engaging in the centre of the squared circle. They bounded from their seconds, La Motta launching searching, arcing hooks from a crouch, while the upright Robinson circled and fended and pawed and then struck with precision. The venue known as the Madhouse on Madison was demolished in 1995 but this was during its heaving prime and the 14,802 spectators roared with delight at each engagement.

At 30 years of age, Robinson was in his own prime. His handlers had sent him to Europe over the Christmas period to keep him away from temptation in Harlem where he was the undisputed Prince. Incredibly, in four weeks overseas, he fought five times in four countries, with France, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany all forming part of his grand tour. A January training camp merely kept him ticking over and ensured his body was fresh for the Bull.

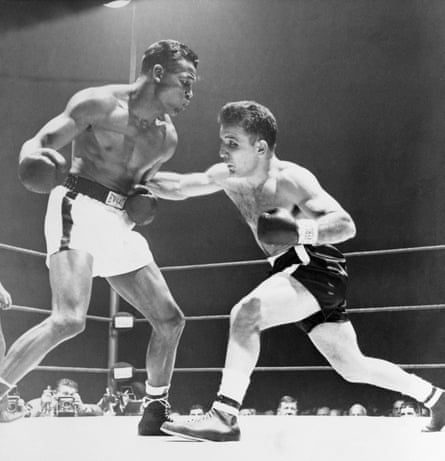

Unlike anyone before or ever since, Robinson’s jab as he back-pedalled was just as hurtful as when he was on the front foot. From the first minute he danced clockwise around La Motta and with almost every bounce he seemed to sting his opponent’s face with that rapier punch. Round after round, La Motta ate it up. His boxing nous is still underrated to this day but against a bona fide ring genius, he had little choice but to keep marching forward and keep swinging. “God gifted me with a big, hard head,” La Motta often said. He’d need it that night of lovers in the Windy City.

Robinson was three inches taller and had a reach five inches longer but occasionally he would allow the Bull into range just to counter him with stunning, short, ambidextrous blows. At other times he would suddenly plant his feet, let his toes grip the canvas floor, and then dig into La Motta’s ribs with ferocious hooks. Then he’d circle again, stretching the distance, and adding yet more miles on La Motta’s ring shoes, while he doubled or trebled or quadrupled his jab. As always, whatever Robinson did, it was carried out with a seamless grace.

Halfway through the scheduled 15 rounds, La Motta may have been ahead on the scorecards as he claimed rounds on aggression and workrate alone. He was also already throwing caution to the wind, commencing attacks from any and every position in the ring. Some of those speculative shots landed and scored but to any trained eye it was clear that, as far as the bigger picture was concerned, everything was progressing exactly according to Robinson’s plan. La Motta was slowing and tiring while Robinson appeared as fresh as his pink Cadillac.

By the ninth, La Motta’s arms and legs looked leaden. He held his left low to protect a now splintered rib cage and had apparently resolved to allow his face to be his last line of defence. Robinson couldn’t miss with his jab but now even his blinding, multi-punch combinations had an alarmingly high strike rate. Despite everything, the Bull kept plodding forward, now little more than a heavy bag with weary limbs. Robinson attacked.

The one-way punishment continued to be meted out in the 10th and 11th until from some otherworldly well, La Motta hauled up a bucket of will and bulldozed Robinson into a corner. A combination of the shock Robinson felt that his prey was still upright, and the 25 unanswered left hooks and overhand rights that La Motta hurled kept the Harlem challenger penned in for a long 15 seconds until he suddenly awoke and blasted his way out. It was to be a courageous last stand that tells you everything you need to know about the heart that beats in the chest of the Bronx Bull.

From that point onwards it was La Motta against gravity. In his previous 95 professional bouts, he had never once had anything other than the rubber soles of his boots on the canvas and, despite Robinson now battering from one side of the ring to the other, he was still not going to go down. At times La Motta’s knees dipped dramatically. At others he appeared to fold in two as if bowing down at Robinson’s feet. But he just wouldn’t drop. And still Robinson attacked.

It is impossible to watch round 13 without the hauntingly beautiful intermezzo from Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana providing subconscious backing music. Scorsese chose the operatic piece to score Raging Bull, the movie which immortalised La Motta on the silver screen, and the poignant, mournful strains of the symphony somehow emphasise the heroic tragedy of La Motta refusing to quit.

By now, he didn’t have a rib cage, but rather an irregular line of fractured bone pushing painfully against muscled torso. He didn’t have a nose, but a mangled bumpy mess of bone and cartilage crushed into place between his eyes. He didn’t really have eyes either, just diaphanous slits within puffed up haematomas. Blood streamed from the corner of one of those damaged peepers and matted the hair on his chest. Still Robinson attacked.

“You can’t do it, you black bastard,” La Motta growled. “You can’t put me on the deck.” Still Robinson attacked. A couple of miles down the road from where Al Capone’s hit men had left a car mechanic and seven of Bugs Moran’s goons in a pool of blood in the original Valentine’s Day Massacre, Robinson attacked and attacked and attacked.

Until the precise moment referee Frank Sikora stepped in to end this slaughter, save La Motta from himself and raise Robinson’s lethally gifted left hand aloft in victory, the Bull was still, inexplicably, moving forward as if inexorably drawn to physical pain and punishment. Robinson knocked out 108 men in his career but La Motta would not be one of them. As the new champ celebrated with his cornermen, La Motta intertwined his gloved fists with the top rope to prevent himself collapsing and his swollen, bloodied lips broke into a sneer.

“Ray,” his hoarse voice shouted as he cleared the warm blood from his throat. “You never put me down, Ray. You never put me down.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion