With the Guardian’s unstoppable rise to global dominance (NOTE: actual dominance may not be global. Or dominant) we at Guardian US thought we’d run a series of articles for newer football fans wishing to improve their knowledge of the game’s history and storylines, hopefully in a way that doesn’t patronise you to within an inch of your life. A warning: If you’re the kind of person that finds the Blizzard too populist this may not be the series for you.

When Arsenal were establishing themselves as the Establishment club during the 1930s, Manchester United were a second-division irrelevance. Then when United began to build their own stellar reputation during the wonders and wakes of the 1950s, Arsenal fell into the doldrums, for a while in the sixties a busted flush. The Gunners bounced back in the early 1970s, but by then United were on the road to the second division again.

It was a very weird business. Arsenal and Manchester United were two of English football’s grandest clubs, sweeping up more than their fair share of the game’s biggest prizes. And yet they never seemed to contest them together.

Even when Alex Ferguson and George Graham were busy building their respective dynasties in the late 1980s, synchronicity was never quite achieved. Fergie was desperate to knock then-dominant Liverpool “off their fucking perch”, but contrary to received wisdom, it was Graham and Arsenal who achieved that. First at the 1987 Littlewoods Cup final, ending a 144-game streak during which, if Ian Rush scored, the Merseysiders didn’t lose; then at Anfield in 1989, Michael Thomas scoring the injury-time winner that snatched the league in the most dramatic and famous circumstances.

United, one slightly illusory second-place finish in 1988 apart, spent most of that particular period faffing around in the middle reaches of the First Division. Then when they finally got their act together, and won the first couple of Premier League titles, becoming the dominant club in the country once more, it was Arsenal’s turn to mill around in mid-table. (By then, they had taken United’s tag of Consolation Cup Side: United had won pots in 1983, 1985, 1990 and 1991, Arsenal two in 1993 and another in 1994. Both sides would have swapped the lot for a solitary league success.)

All very strange. There had been a brouhaha in 1987, when the late, lamented Arsenal midfielder David Rocastle was sent off at Old Trafford for a retaliatory challenge on Norman Whiteside, an act that instigated some hot debate on the touchline involving several members of both dugouts. That was followed a year later by another hilariously petty row in the fifth-round of the FA Cup, when United striker Brian McClair missed a late penalty that would have forced a replay, and was openly mocked by Arsenal full-back Nigel Winterburn, who accompanied his opponent all the way back to the halfway line, offering him sage advice for the placement of his next spot kick while doing so.

Then there was a glorious – well, it was great fun to watch – 21-man brawl between the two teams at Old Trafford in the league in October 1990. Graham’s Arsenal were becoming past masters at this, having been involved in a 19-man stramash with Norwich City at Highbury the year before. This particular drunken-sailor dance saw Winterburn lunge in on his old pal McClair, Paul Ince dispatch Anders Limpar (who had been entangled with Denis Irwin) into the hoardings, and McClair dump Tony Adams on his ass. No red cards! And let’s not be pious, it was marvellous entertainment. More, please! Both teams were docked points for their bother, though Arsenal still won the title.

And yet it still didn’t feel like a proper rivalry.

But these were two of the biggest clubs in world football. And it had to happen at some point.

It happened. And it all started happening when Arsène Wenger came to town in September 1996. By now, United were firmly established as the masters of the Premier League domain. Norwich City, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers and Newcastle United had all taken turns to come at the king, but all bar Rovers would all miss, and even they couldn’t sustain their challenge over the long haul: once they’d pipped United to the 1995 title, all their energy was spent.

But the new man on the scene was up for it, and raring to go. Wenger quickly transformed Arsenal into a leaner, fitter, fighting machine. Leaner and fitter: much to the dismay of players long in the tooth and hollow of leg, he banned Mars bars and lager, introducing radical new concepts such as eating vegetables and drinking water. Fighting: yes, they did that as well. From the off, Wenger’s Arsenal went toe to toe with Fergie’s side, swinging metaphorical and sometimes actual haymakers. First up, Ian Wright versus Peter Schmeichel. The pair locked horns rather unpleasantly: there were allegations of racial abuse against the keeper, while Wright could easily have broken Schmeichel’s leg.

United faced a cluttered schedule at the end of that season as they battled (and eventually easily overcame) Liverpool, Newcastle and Wenger’s emerging Arsenal for the title. Fergie requested some extra time in which to fairly fulfil his side’s fixtures. He was denied, becoming hopping mad after Wenger had got involved in an argument which didn’t concern him. “It’s wrong the league programme is extended so United can rest up and win everything,” Wenger opined. Fergie spluttered by way of response: “He’s coming here from Japan and telling us how to run our game!” Horns were again locked.

The rivalry truly caught fire in the 1997-98 season. United should have won the title: they were at one point 12 clear at the top. But Arsenal - now blessed with the French midfielders Patrick Vieira and Emmanuel Petit, soon to win the World Cup - overhauled them with a ten-game winning sequence towards the end of the campaign. The turning point, and signature match of their title win, was a 1-0 victory at Old Trafford, Marc Overmars tearing clear to score the decider late in the second half. Arsenal went on to secure the double.

The year after, of course, United went one better. Their famous 1999 Treble of Premier League, FA Cup and Champions League stands as the greatest single achievement in English football history. Yet it could all so easily have ended as another Arsenal double. The thin lines between success and failure, mapped out right here in all their topographic splendour. United won the league by a point, but only because Arsenal lost their penultimate game at Leeds. Both teams had previously gone undefeated in the league between December and May.

One of the great league battles, and yet it’s almost forgotten these days, obscured by the long shadows of the most epic FA Cup encounter of all time, a 2-1 semi-final win for United at Villa Park, Dennis Bergkamp missing a last-minute penalty, Roy Keane seeing red, Vieira gifting Ryan Giggs the ball on the halfway line to set up that solo dribble and hairy shirt-twirling celebration. After the match, Tony Adams and Lee Dixon made a point of seeking out their vanquishers to congratulate each and every one of them. There’s nice.

The convivial sporting atmosphere couldn’t last. United, entering their imperial phase, won the next two Premier Leagues with ease. The extent of their dominance at the time was illustrated by a 6-1 thumping of Arsenal, their closest challengers, at Old Trafford in February 2001. Poor Igors Stepanovs.

Arsenal eventually responded by winning the last 13 games of the 2001-02 season to wrest the title back. They sealed the deal at Old Trafford, Sylvain Wiltord scoring the only goal of the game. In the post-match comedown, Fergie insisted United were still the better team. “Everyone thinks he has the prettiest wife at home,” retorted Wenger. Fergie opted to take the witty allusion literally, assuming his wife Cathy had been slighted. It kept the blood boiling, and the rivalry going.

United returned the favour the following year, overhauling a large Arsenal lead. Ruud van Nistelrooy, Ole Solskjaer and Paul Scholes particularly blossomed during the run-in, which saw United win nine of their last ten, and draw the other 2-2 at Highbury. It was a decisive evening’s work: United were by far the better side, sapping Arsenal’s confidence, while Sol Campbell was sent off for crumping his elbow into Soskjaer’s babycoupon, the big defender’s subsequent suspension proving costly on the run-in.

Overhauling a seemingly superior Arsenal – spectacularly so – was arguably United’s greatest title triumph. Though it wasn’t all plain sailing for them that season. In February, Arsenal knocked United out of the FA Cup at Old Trafford. Ryan Giggs missed an open goal. In the dressing room afterwards, Fergie didn’t miss David Beckham’s face with a boot carelessly kicked mid-rant. The pair had seconds before reportedly traded the c-word during a heated debrief, and it was the beginning of the end for Becks at United. He would leave for Real Madrid at the end of the season.

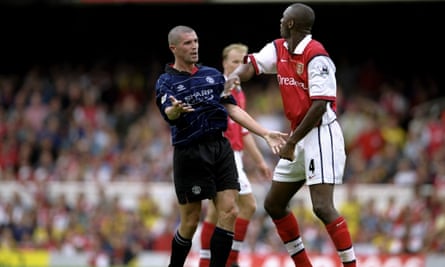

Then – shades of the George Graham era – came another widescreen war. Early in the 2003-04 season, the teams met Old Trafford. Vieira was sent off for a wholly unnecessary kick at Van Nistelrooy. He had to be led off by, of all people, the renowned diplomat Boutros Boutros-Keane. Van Nistelrooy had a chance to score the winner from the penalty spot in injury time, but hit the crossbar. Martin Keown, seething with perceived injustice, and a general dislike of the striker, who Arsenal perceived to be regularly trying it on, got right up in the striker’s grille. Arsenal escaped with a draw, and remained unbeaten in the league. Given it was only September, that was unremarkable at the time. But we all know how the rest of the season panned out for the Invincibles, who became the first team since Preston North End in 1888-89 to go through an entire campaign undefeated.

United enjoyed some not inconsequential revenge, beating Arsenal in the FA Cup semi. It arguably denied the Gunners a treble of their own; they would surely have beaten Millwall in the final, while a few days after the United defeat, an unfancied Chelsea knocked them out of the Champions League quarter-finals at Highbury. Only Monaco and Porto lay further ahead. Arsenal’s best chance of becoming European champions – and, counterfactually, extinguishing Jose Mourinho’s emergence at source – had evaporated. United had taken the puff from their sails.

Not once, but twice. Because there was only one way Arsenal’s unbeaten run in the league would end. Going for the 50 not out, they lost 2-0 at Old Trafford. Van Nistelrooy should have been sent off for a dreadful tackle on Ashley Cole, but instead scored a cathartic penalty. It all kicked off in the tunnel after the game. Wenger spoiled for a row with Ferguson, but it was Cesc Fabregas who dealt the memorable blow, comically landing a slice of pizza on the United manager’s face.

Inevitably the return fixture at Highbury was fraught. In the tunnel before kick-off, Vieira played a few mind games with Gary Neville. Backing up his man, Keane responded by promising Vieira that “I’ll see you out there”. Viera scored the first goal of a feisty match, but Keane drove his side on to a 4-2 win. However, it was Mourinho’s Chelsea who won the league that season, the United-Arsenal rivalry instantly downgraded as a result. Arsenal did, however, get the last laugh of the eight-season period during which the pair dominated English football: they beat United in the FA Cup final that year, Vieira scoring the deciding penalty kick in a shootout.

Since then, it’s been a whole lot calmer, though United’s 8-2 win in August 2011 and Arsenal’s FA Cup quarter-final win at Old Trafford last season, Angel di Maria doing his best to stoke the fires again, stand out. Another memorable rumpus this weekend? We’re due something.

- Many thanks to Rob Smyth who – heads up! – is currently writing I’ll See You Out There (Bloomsbury), a book certain to become the definitive tome on this great rivalry

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion