Surgeons in every hospital in the country will be required to run through a brief checklist before they operate, which will include establishing the identity of the patient and the operation they need, after a trial showed the simple procedure could cut deaths by 40%.

Eminent surgeons expressed shock and surprise after the use of a two-minute checklist to ensure basic procedures had been done in eight hospitals in rich and poor countries around the world, including St Mary's in Paddington, London, revealed the scale of human error. Many surgeons were strongly opposed to using the list, which has to be read aloud to the team in the operating theatre, until they realised how much safer it made operations. Complications were cut by a third.

"The results from the pilot study are startling," said Dr Atul Gawande, associate professor at Harvard School of Public Health and lead for the Safe Surgery project devised by the World Health Organisation. "They indicate that gaps in teamwork and safety practices in surgery are substantial in countries both rich and poor.

"With the annual global volume of surgery now exceeding 234m [operations], the use of the WHO checklist could reduce deaths and disabilities by millions. There should be no time wasted in introducing these checklists to help surgical teams do their best work to save lives."

Britain responded immediately, with a nationwide alert issued by the National Patient Safety Agency. The agency issued a slightly modified version of the list and said it would require all hospitals to use it by 2010. Surgeons will be required to tick every box and sign to show they have complied.

The chief medical officer for England, Sir Liam Donaldson, who is chair of the WHO World Alliance for Patient Safety, said the alert was critical to safer surgery in the UK. "Our aim must be to reduce patient deaths and the level of surgical complications," he said. "By giving our hospitals clear guidelines and a strict timeline for implementing the alert, we are highlighting the importance of patient safety."

There are more than 8m surgical procedures carried out every year in the UK. During 2007, 129,419 incidents where something went wrong were reported to the agency. In over 1,000, patients suffered severe harm and 271 patients died.

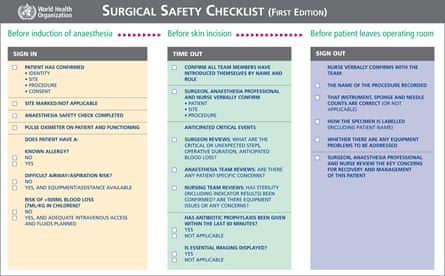

Dr Gawande, whose study was published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, said pausing for a moment to take stock and make sure the entire surgical team agreed on what they were about to do could prevent some of the very common problems that led to complications and sometimes even death, such as infections and the management of bleeding. The questions on the list ask whether the patient has been given an antibiotic, whether breathing problems are anticipated and whether the patient has a known allergy. Once the anaesthetic has been given, all team members – nurses, surgeons and other theatre staff – must introduce themselves and be asked whether they have any concerns. After the operation, the number of sponges and needles must be counted to ensure none were left inside the patient and the team must discuss any concerns about the patient's recovery.

"We've become very good at making sure most of these things happen most of the time but not very good at ensuring they happen all of the time," said Dr Gawande. He himself had used the checklist for nine months during operations at Harvard, he said, although at first he had supposed he did not really need it. "I do eight to 10 operations a week. I don't go through a week without finding something and I'm convinced it saved one patient's life," he said.

He met "significant resistance" to the idea from surgeons, he said. About half said it made sense, 30% were unenthusiastic but complied and 20% said they thought it was a waste of time. Some refused to use it.

"But people became aware that the results were improving as they went along, so we had a learning curve," he said. By the end, about 20% of surgeons said they didn't like the checklist, but 93% said they would want it used if they were undergoing an operation themselves.

The eight trial hospitals were in a mix of developed and developing countries – Jordan, India, the USA, Tanzania, the Philippines, Canada, the UK and New Zealand, but the reduction in deaths and damage were very similar across the world. More patients were saved from harm in developing countries because they had higher rates of damage to begin with – not least because people were more sick and needed emergency operations.