Neanderthals made extensive use of coastal environments, munching on fish, crabs and mussels, researchers have found, in the latest study to reveal similarities between modern humans and our big-browed cousins.

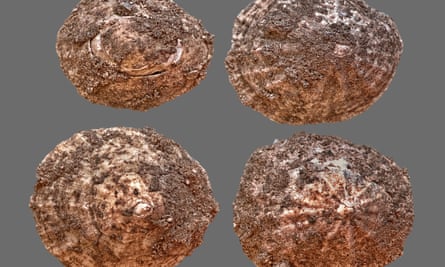

Until now, many Neanderthal sites had shown only small-scale use of marine resources; for example, scattered shells. But now archaeologists have excavated a cave on the coast of Portugal and discovered a huge, structured deposit of remains, including from mussels and limpets, dating to between 106,000 and 86,000 years ago.

Researchers say the discovery shows that Neanderthals systematically collected seafood: in some layers the density of shells was as high as 370kg per cubic metre. They say this is exciting because the use of marine resources on such a scale and in such a way had previously been thought to be a trait of anatomically modern humans.

Prof João Zilhão, of the University of Barcelona, a co-author of the report, said the discovery added to a growing body of research suggesting modern humans and Neanderthals were very similar.

“I feel myself uncomfortable with the comparison between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, because the bottom line is Neanderthals were Homo sapiens too,” he said. “Not only was there extensive interbreeding, and such interbreeding was the norm and not the exception, but also in every single aspect of cognition and behaviour for which we have archaeological evidence, Neanderthals pass the sapiens test with outstanding marks.”

The findings chime with recent evidence that Neanderthals had “surfers’ ear” and may have dived to collect shells for use as tools. Previous finds in Spain have shown they decorated seashells and were producing rock art 65,000 years ago.

“Forget about this Hollywood-like image of the Neanderthal as this half-naked primitive that roamed the steppe tundra of northern Europe hunting for mammoths and other megafauna with poor and inefficient weapons,” said Zilhão. “The real Neanderthal is the Neanderthal who is in southern Europe.”

The discovery appears to throws cold water on the idea that the marine-rich diet of modern humans, high in fatty acids, helped them to outcompete Neanderthals as a result of better cognition.

“If [marine foods] were important to modern humans, then they were important for Neanderthals as well – or perhaps they did not have the importance people have been attributing to them,” said Zilhão, noting that in any case few modern humans were living by the coast.

Writing in the journal Science, researchers reveal how the newly excavated site, which was about 2km or less from the coast when occupied by Neanderthals, contained a plethora of stone tools, roasted plant matter and remains from horses and deer, as well as from eels, sharks, seals, crabs and waterfowl, suggesting a diverse diet.

Zilhão said the find also shed some light on Neanderthal fishing practices, noting that they must have had baskets or bags. “You cannot walk 2,000m with a catch of 10 or 20 kilos of shells in your hands,” he said, adding that the Neanderthal population also probably understood that shellfish collected at the wrong time could be toxic.

The team say the dearth of other huge shell deposits in Europe could be down to a lack of preservation: shellfish could not be transported far from the coast, and hence many such deposits in northern Europe would have been destroyed as polar ice caps advanced, while elsewhere they may have been submerged as the sea rose to today’s levels.

The stretch of Portuguese coast where the new find was made is perhaps the only location locally where such deposits could have been preserved, they say. South Africa, by contrast, experienced an uplift of the land, meaning many such deposits have been preserved.

Dr Matthew Pope, a Neanderthal researcher at the UCL Institute of Archaeology who was not involved in the study, said its findings were significant.

“We have increasingly recognised the sophistication of Neanderthal behaviour, but one thing that continued to mark out the behavioural evolution of modern humans in Africa was the appearance of systematic collection of marine resources, and this marked a difference between the two populations,” he said. “Evidence like this is important in showing Neanderthal populations had the capability for systematic exploitation of marine resources.”