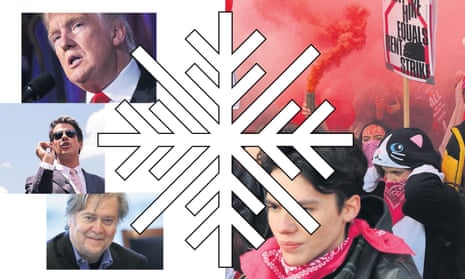

Between the immediate aftermath of Brexit and the US presidential election, one insult began to seem inescapable, mostly lobbed from the right to the left: “snowflake.” Independent MEP Janice Atkinson, who was expelled from Ukip over allegations of expenses fraud, wrote a piece for the Huffington Post decrying the “wet, teary and quite frankly ludicrous outpouring of grief emails” she had received post-referendum as “snowflake nonsense”. The far-right news site Breitbart, whose executive chairman Stephen Bannon is now Donald Trump’s chief strategist, threw it around with abandon, using it as a scattershot insult against journalists, celebrities and millennials who objected to Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric; its UK site used it last week to criticise a proposed “class liberation officer” at an Oxford college who would provide more support for working-class students.

On an episode of his long-running podcast in August, Bret Easton Ellis discussed the criticism of a lascivious LA Weekly story about the pop star Sky Ferreira with a furious riposte to what he calls “little snowflake justice warriors”: “Oh, little snowflakes, when did you all become grandmothers and society matrons, clutching your pearls in horror at someone who has an opinion about something, a way of expressing themselves that’s not the mirror image of yours, you snivelling little weak-ass narcissists?”

In September, Breitbart’s Milo Yiannopoulos used it to dismiss a protester at a talk in Houston, declaring that it was his event, not the “silver-haired snowflake show”. “Madam, I’m grateful to you for coming, but to be quite honest with you, fuck your feelings,” he told her, as the crowd roared “USA! USA! USA!” in the background. “Fuck your feelings” is a crude expression of what snowflake has come to mean, but it is succinct and not entirely inaccurate.

The term has undergone a curious journey to become the most combustible insult of 2016. It emerged a few years ago on American campuses as a means of criticising the hypersensitivity of a younger generation, where it was tangled up in the debate over safe spaces and no platforming. A much-memed line from Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club expresses a very early version of the sentiment in 1996: “You are not special. You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake. You are the same organic and decaying matter as everyone else.”

But recently it has widened its reach, and in doing so, diluted its meaning. It has been a favoured phrase of some tabloids, which have used it as a means of expressing generic disdain for young people who are behaving differently from people older than them. Whenever a new survey appears that claims young people are having less sex, or drinking less alcohol, or having less fun, it’s there as a handy one-word explanation: they are snowflakes.

Until very recently, to call someone a snowflake would have involved the word “generation”, too, as it was typically used to describe, or insult, a person in their late teens or early 20s. At the start of November, the Collins English Dictionary added “snowflake generation” to its words of the year list, where it sits alongside other vogue-ish new additions such as “Brexit” and “hygge”. The Collins definition is as follows: “The young adults of the 2010s, viewed as being less resilient and more prone to taking offence than previous generations”. Depending on what you read, being part of the “snowflake generation” may be as benign as taking selfies or talking about feelings too much, or it may infer a sense of entitlement, an untamed narcissism, or a form of identity politics that is resistant to free speech.

The phrase came to prominence in the UK at the beginning of 2016, after Claire Fox, director of the thinktank Institute of Ideas, used it in her book I Find That Offensive to address a generation of young people whom she calls “easily offended and thin-skinned”. Fox is clearly a natural provocateur and has written about generation snowflake in bulldozing articles for the Spectator (How We Train Our Kids to Be Censorious Cry-Babies) and for the Daily Mail (Why Today’s Young Women Are Just So Feeble). As intended, both caused considerable debate – which is precisely what Fox claims generation snowflake are losing their ability to do.

On the day we speak, she is bristling over an appearance at a school in Hertfordshire, where some students had objected to her being invited in the first place. “Several of the students said, ‘How dare you invite this terrible woman to speak?’ and said to me that I’d come there and upset them. They were giving a literal demonstration of my very speech,” she says.

Much of the debate around this generation of “whingers”, as she later calls them – slightly naughtily, as she also admits that obviously not every young person is a whinger and the phrase “generation snowflake” is more useful “to demonstrate the closing down of free speech and the demand for attention” – is to do with what has been happening on university campuses in the last decade or so. She is appalled by the move towards “no platforming”, in which speakers who have views deemed by students to be controversial or offensive, from Germaine Greer to Peter Tatchell, have been barred or disinvited from speaking events. Regardless of whether their opinions are objectionable or abhorrent, Fox insists we must hear views that do not agree with our own in order to learn how to tackle them.

“People have given up trying to persuade other people, and trying to win the argument,” she says. “Demands for safe spaces are to ‘stop people coming in here, so we’re not to be exposed to this. We demand our lecturers don’t introduce these ideas.’ It’s infantilising. It’s the opposite of rebellion. It has not got any intellectual weight. I want a generation to come forth with a new philosophy of freedom, rather than playing out in practice that their teachers and parents raised them as cotton-wool kids.”

Try talking to a person whose age puts them into the “generation snowflake” category, however, and it’s apparent that the most offensive thing about the whole offence debate is being called easily offended. In June, in reaction to a slew of articles decrying wimpy, moany millennials, Angus Harrison wrote an article for Vice in which he pointed out that young people were being labelled snowflakes at the same time as being called “Generation Sensible” or “new young fogeys”. “Young people today are really old and boring and sensible. Except, they are also babies, totally unprepared for the adult world. Make sense? No, it doesn’t,” he wrote.

“I’m confused!” says Liv Little, 22-year-old editor-in-chief of the magazine gal-dem, who was recently selected as one of the BBC’s 100 most influential and inspirational women of 2016. She finds the idea that she and her peers are self-obsessed and unable to cope with the world absurd. “I don’t get what they want to happen. Do they want people to be quiet and suck it up? Do they want people to have breakdowns and be really unhappy and accept a political system that doesn’t represent them?”

Little set up gal-dem as a student in 2015, in response to a lack of diversity at her own university. It has since grown to a collective of more than 70 women of colour and recently won a prestigious award for Online Comment Site of the Year. She says that what she sees is people taking that feeling that the world isn’t working for them and turning it into something positive and active. “A lot of offensive stuff is happening. Why should people not be offended? People are offended but they’re using that feeling of being offended to bring about change. Things are so dire sometimes that it’s necessary. If I want to carve out a safe space, why shouldn’t I?”

Much of the disagreement is down to how you define these endlessly complex sticking points of campus debate. For Fox, a “safe space” is a censorious exclusionary zone. For Little, it is a starting point that doesn’t hurt anyone, not least the people who are left out. “Creating safe spaces is good for us, it’s good for our mental health, it’s good for us in terms of preparing and organising, and then when we want to welcome people in to our spaces, we can. How often have women or people of colour been excluded from so many spaces in the world? And then people are crying because we’re creating spaces for us. It doesn’t make sense!”

Often the argument that younger people are weaker and less able to cope feels like a dressed-up way of saying “things were better in my day”. We live in a time of stark generational division and animosity, in which the year’s huge political decisions, the ones that have seemed most cataclysmic – Brexit, Trump – have been decided by older voters whose opinions are vastly different from those of younger voters. Millennials are living in a time of economic uncertainty, without guaranteed access to the affordable housing, free education and decent job market enjoyed by the generations before them. “I think our generation is really under pressure,” says Little. “I look around at my peers, at women around me, and they’re all working themselves into the ground. It’s a difficult climate. We’ve sucked it up for a while and now we’re trying to take control,” says Little. “In our case, it’s for women of colour. And that’s just inherently a good thing.”

I ask her if there’s any sympathetic part of her that can understand why the people who are calling her generation snowflakes might feel inclined to do so. “Err.” There’s a long pause, in which she really does sound like she’s trying. “Um. No. I just see it as an extension of entitlement.”

When the supposedly entitled are calling their detractors entitled for calling them entitled, it’s clear that whatever impact “snowflake” may have had as an insult is in the process of being neutralised. In a remarkably speedy turnaround of its intended usage, the left have started to reclaim it, throwing it back at the people who were using it against them in the first place. Trump was repeatedly labelled a snowflake earlier this month during the row over Mike Pence getting booed during a performance of Hamilton on Broadway. Trump said the theatre should always be a “safe space”, sounding not unlike a university protester himself; the irony was not lost on many commentators, who called him “the most special snowflake of all”. Search Twitter for “snowflake” alongside the name of any prominent political figure on either side of the spectrum and you’ll find a black hole of supporters and detractors barking the word back and forth at each other.

So if the right are calling the left snowflakes for being liberal, and the left are calling the right snowflakes for expressing offence, and the old are calling the young snowflakes for being too thin-skinned, and the young are pointing out that the older generation seem to be the most offended by what they’re doing, then the only winner is the phrase itself. It’s particularly effective given that there’s really no comeback to it: in calling someone a snowflake, you are not just shutting down their opinion, but telling them off for being offended that you are doing so. And if you, the snowflake, are offended, you are simply proving that you’re a snowflake. It’s a handcuff of an insult and nobody has the key.

I called Jim Dale, senior meteorologist at British Weather Services, to see if it was ever an effective analogy in the first place. He says he can see why it was chosen. “On their own, snowflakes are lightweight. Whichever way the wind blows, they will just be taken with it. Collectively, though, it’s a different story. A lot of snowflakes together can make for a blizzard, or they can make for a very big dump of snow. In which case, people will start to look up.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion