I am not British. This came as a bit of surprise to me, given I was born in London to parents who had themselves been born in London, with a family history as pub tenants in the East End going back to the 1860s at least.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

But according to a DNA kit from Ancestry.com I’m only 9% British. It tells me I’m 47% Irish, 33% Belgian/Dutch/German/French and 7% Scandinavian. But how much should we trust these DNA kits that are so widely advertised on television – and crucially, what do they do with our deeply personal DNA data? Share it with anyone else on the globe seems to be the answer.

Two weeks ago I received an email that I first thought must be a scam. It was from my “cousin” Karen in south Australia, telling me we’re connected and asking for more details on my Irish and Iberian background (it seems I’m also a bit Spanish). Yeah right, fourth cousin Karen. How long, I wondered, before some nefarious request emerged for cash … then I remembered I had done a saliva test with Ancestry.com a year ago as part of a press thing, but had never chased up the results.

It turns out that all I had to do was log on to Ancestry to see my results. Sure enough cousin Karen is real (hi Karen, so sorry) and so, it seems, is my DNA profile. But how accurate are these tests?

The home DNA test market is made up of many different companies, with deals priced at £49 (MyHeritageDNA), £99 (Living DNA) and through to £129 (23andMe). Ancestry is the global market leader, with its main product priced at £79. This is the one Guardian Money tested.

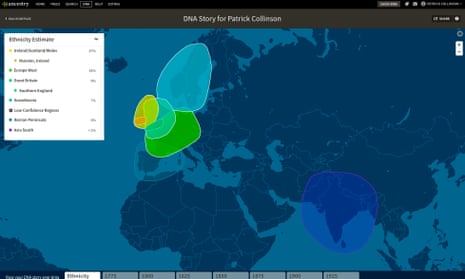

The results are far from instant: once you send away your saliva sample to the firm, it can be six to eight weeks before they are posted back to you. It’s all very online – users log in for their results, and are presented with a page that gives their ethnicity estimate broken down into countries and regions across the world. Ancestry then links the individual with their “cousins” who have very similar DNA, while also showing maps of the emigration pattern of that person’s DNA going back hundreds of years.

In my case, the Irish ethnicity result was impressive: Ancestry located my Irish DNA to Munster province, drawing a circle centred on the town in county Tipperary almost precisely where my maternal grandmother was born. It was almost spookily accurate, although at 47% indicated a much greater degree of Irish ethnicity than the 25% I expected. But as Ancestry points out, half of the 5m DNA tests taken by its customers (mostly in the US, the UK and Australia) show a reading of at least 10% Irish DNA.

I’m now connected to a remarkable “118 fourth cousins or closer” around the world. The site even draws a map of early emigration, suggesting that my DNA is connected with an individual who left the Tipperary area to live in Rochester, New York state, around 1775 – and by the 1850s the map is almost saturated with Collinson DNA (it would probably have been Ryan then) fleeing the Irish famine for every part of the globe.

But can I really be just 9% British? On my father’s side our English history and the census records are quite clear. George Collinson leaves Oxfordshire in the 1840s for London in the 1860s, managing the Salmon and Ball pub in Spitalfields market, and by the 1930s my grand matriarch of a grandmother controlled three East End pubs from her base at the Duke of York in Bow. So how can Ancestry produce a result which says I am just 9% “Great British”? And can I possibly tell my Francophobe, Spitfire-saluting, born-in-the-sound-of-Bow-Bells, seaside-town-retired, Conservative Brexit-fan father that, er, he may not actually be that English?

Ancestry’s DNA expert Mike Mulligan (93% Irish – everyone’s email at Ancestry gives their ethnicity breakdown) admits that the ethnicity percentage is a “top line” estimate derived from just a very small part of our DNA, a couple of letters long in the 3bn letters that make up our DNA, and that there are a lot of “inferences” made from the data. Precision is still a problem for DNA kits. Mulligan says that the Irish, Scots and Welsh are “almost indistinguishable from a DNA point of view”. Meanwhile, when it comes to western Europe “it is the most traipsed-about part of the planet. The amount of DNA that has been blurred together is incredible.” Remarkably, DNA testers can’t really tell the difference between German and French DNA.

What’s more, the south of England, and specifically London, come under Ancestry’s “Europe West” ethnicity designation, but the Midlands and the north do not. That’s because London has for centuries traded with, and opened its doors to, people from Europe, and Londoners’ DNA is not that distinguishable from others in western Europe, says Mulligan. So my 9% Great British and 33% Europe West reading could actually be 42% London – which accords far more with my own genealogical research. And while Ancestry gives exact figures for ethnicity, click through and you see that the parameters are huge – my reading for Europe West gave a percentage range from 3%-62%.

Given the fuzziness of these DNA results, how was Ancestry able to link me specifically to Munster in Ireland? It says its research has established unique DNA signatures for some “genetic communities” of densely connected clusters of people at a sub-country level (research that has been peer-reviewed and published in Nature). Munster is one of them. In Sicily, for example, it has identified five DNA clusters on the island because there was a long history of clannish intermarriage. But other people buying DNA kits may find their origins are very broad brush, covering areas with populations of 100s of millions.

I immediately shared my DNA results with my six brothers and sisters, assuming that their figures would be identical. I was wrong. You should inherit 25% from each grandparent, but it could be slightly more or slightly less. So while I might be 47% Irish, my brother or sister could have a reading in the low 40s.

Low percentage ethnicity readings should be treated very cautiously, says Ancestry. I’m 1% Indian, according to Ancestry, but Mulligan admits that could simply be “statistical noise”. He says what most excites its US customers is not finding that most have European heritage (no surprises there), but if their results show any Native American. Very often it’s just 1% or 2% and can’t be seen as robust enough evidence to suggest a true native heritage.

In Britain, it seems we get most excited about finding Viking ancestors. While I’m 7% Scandinavian according to Ancestry, Mulligan warns me against assuming a Viking connection. A blog post on the site says: “If you have Scandinavian ethnicity as part of your estimate, then your DNA is similar to a group of modern day people in our AncestryDNA reference panel with deep roots in Scandinavia. That modern distinction is important – the test does not compare your DNA to any ancient group of people. In other words, the test does not compare your DNA to any ‘Viking DNA’ (if this even could be defined).” However it adds that among the people it has tested so far in the UK, the highest Scandinavian percentages are found in the north-east of England, once run by Viking invaders.

What about the thorny privacy issues surrounding DNA? Could my test somehow link me to an unsolved crime with the police knocking at my door? Ancestry says that in all its tests there has only ever been one request from the police for data. But it has found sons and daughters who, ahem, weren’t actually connected to the person they believed to be their father.

My own conclusion? It was fun seeing the results, but what does it really add up to? I’m not mad keen to find much-removed eighth cousins. I’m no scientist, and I’m still a little baffled as to how all this works. I’ve learned I’m probably a mixture of Irish/Celtic, plus the Saxon, Jute and Scandinavian tribes that invaded Britain and intermarried with the existing population.

In other words, I’m probably pretty similar to most people on this wet and windy island full of blow-ins.

The science behind the kits

Academic research into home DNA kits has done much to debunk the more outlandish claims made by some companies, such as “DNA satnavs” that can direct you to your ancient home village (they can be out by hundreds of miles). Debbie Kennett, research associate at the department of genetics at University College London, says we should take exact ethnicity percentages “with a very large pinch of salt”, though cousin matching (up to second cousin) is very accurate. Use them for genealogical research, she says, but any idea they can accurately link you to Romans, Vikings or ancient Native Americans is just bunk.

Crucially, in 2015 she tested not just Ancestry’s kit, but also those from two other suppliers – and got worryingly different results. Ancestry told Kennett she was 21% British, 20% Irish and 47% Europe West. FamilyTreeDNA told her she was 57% British Isles (including Ireland) and 22% Western and Central Europe. 23andMe gave a range: its “conservative” view was that she was 99.7% European, while its “speculative” view was that she was 56.1% British and Irish, 13.4% French and German, and a further 24% broadly northern European.

Given that Kennett has done extensive research on her background, and knows that all her lines within the past 500 years are from the British Isles, these results will probably deter many from spending money on the kits.

“It’s all about interpretation. For genealogical purposes they are useful for cousin matching. But what is much less reliable is the ethnicity figures. That is generally reliable only at the continental level.” She accepts that the science behind Ancestry’s genetic communities is good, but adds: “It’s based not on segments of your DNA, but on markers shared by people in that population.” She adds that the science is improving all the time.

How does she rate the different companies? “Living DNA is best for the most detailed coverage of the British Isles, Ancestry is first choice for cousin matching, MyHeritgage has good coverage in eastern Europe and Italy, while 23andMe has got health results. They all have pros and cons.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion