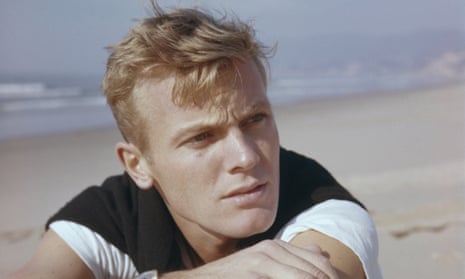

Hollywood heartthrob Tab Hunter, the beloved boy-next-door of 1950s Warner Brothers classics like Battle Cry, The Burning Hills and Damn Yankees, died on Sunday at the age of 86. A blonde, square-jawed and wholesome symbol of mid-century American masculinity, Hunter, born in 1931 as Arthur Gelien, was gay but kept his sexuality a secret for the bulk of his career, until coming out in his 2005 autobiography Tab Hunter Confidential: The Making of a Movie Star.

“Tab passed away tonight three days shy of his 87th birthday,” read a post on the late actor’s Facebook page early Monday morning. “Please honor his memory by saying a prayer on his behalf. He would have liked that.”

A product of an era that was famously inhospitable to gay entertainers, Hunter kept up secret romances with film star Anthony Perkins and figure skater Ronnie Robertson as movie studios trotted him out alongside screen sirens Natalie Wood and Debbie Reynolds, with whom he’d go on pretend dates. Before the LGBT rights movement broke open in the late 60s, Hunter’s sexual orientation, like that of his contemporary Rock Hudson, was handled with innuendo by journalists covering the revolving door of romances among Tinseltown’s top brass.

The gossip columns of the day, penned by Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper, “made subtle references” to his sexuality, as Hunter wrote in the Hollywood Reporter in 2015, “wondering when I was going to settle down with a nice girl and then, after the studio began pairing me with my dear friend Natalie Wood on faux-dates, asking if I was ‘the sort of guy’ she wanted to end up with”.

Ultimately, Hunter would end up with producer Allan Glaser, his partner of 36 years. But not before an article in Confidential, the bimonthly gossip rag from which Hunter’s memoir borrows its name, reported on the then 24-year-old’s involvement in an arrest at a “limp-wristed pajama party” where other gay males were in attendance. The article, Hunter felt, insinuated he’d been party to a “gay orgy”, a rumor that might have torpedoed his career given the contemporaneous moral panic around homosexuality and the “lavender scare” that led to mass firings.

“When the Confidential article came out,” he recalled, “I thought my career was over.”

But Hunter, who by the late 50s felt “the publicity had exceeded the product”, was actually entering the most prolific stretch of his career. In 1956, he starred opposite Wood in The Burning Hills, a Western revenge tale about a pair of young lovers. The two teamed up again two years later in the 1958 romantic comedy The Girl He Left Behind. A year before that, Hunter’s version of the song Young Love charted at number one on the Billboard Top 100, introducing the world to his dreamy baritone. And, in 1958, he proved his musical bona fides yet again starring in Damn Yankees, an All-American movie musical that cemented Hunter’s status as the comely golden boy opposite James Dean’s rebel without a cause.

Bosley Crowther, reviewing the film adaptation of the 1955 musical in the New York Times, said Hunter was in possession of “the clean, naive look of a lad breaking into the big leagues and into the magical company of a first-rate star”.

That star, however, would begin to dim in the early 1960s, when Hunter bought himself out of his contract with Warner Bros for $100,000 and was replaced by Troy Donahue. He’d continue to make movies and appear on television – most notably in the short-lived Tab Hunter Show – but found himself mostly in B pictures like Operation Bikini while working the dinner theatre circuit in shows like Bye, Bye Birdie and The Tender Trap. As the studio era ended, the movie business changed inalterably; Hunter, as he says in his memoir, had to bite the hand that fed him stardom.

“In my professional life, I longed to be more than the sigh guy,” he wrote in Tab Hunter Confidential, which was made into a documentary of the same name in 2015. “In my personal life, I was quite a different Boy Next Door than the one Mr and Mrs Middle America imagined me to be.”

Through the 60s and 70s, Hunter decamped to Europe, where he spent time in Capri, Monte Carlo, and Rome liaising with Luchino Visconti and Etchika Choureau while carrying on an affair with the Soviet dancer Rudolf Nureyev. What he really wanted, though, was to “chuck the whole rat race and move to Virginia’s horse country”. So, in 1973, he began leasing farms in rural getaways like Oregon and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, paying the bills by touring with a dinner theatre troupe.

In 1977, Hunter attempted a comeback when he replaced Philip Burns as George Shumway in the late-night series Forever Fernwood. But what would revitalize his career in earnest was a phone call from John Waters, the transgressive gay film-maker whose campy sensibility hadn’t yet been fully embraced beyond midnight moviegoers. Waters had called to cast Hunter in Polyester, opposite drag queen and Waters muse Divine.

“How would you feel about kissing a 350-pound transvestite?” Waters supposedly asked Hunter. “Well, I’m sure I’ve kissed a hell of a lot worse!” he replied. The film would become a resounding success, Waters’ first in the mainstream, and the unlikely pairing that was Hunter and Divine would be reprised in the 1985 comic western Lust in the Dust. It was on the set of that film where Hunter met Glaser, the producer with whom he’d spend the next three and a half decades.

It was not until 2005, though, that Hunter came out publicly, using his memoir (co-written by Eddie Muller) to pre-empt another tell-all that was also in the works. Its opening words – “I hate labels” – reflect Hunter’s discomfort with an industry hellbent on typecasting him as the Sigh Guy, the Boy Next Door and “the even more ludicrous Swoon Bait”. But, in its Inside Baseball approach to revealing the inner workings of Hollywood before, during and after the studio era, it is a remarkably insightful, confident account of and by one of Hollywood’s first gay movie stars, a label by which the famously self-effacing Hunter would surely be chagrined.

In death, though, Tab Hunter’s legend won’t fade. The 2015 documentary adapted from his memoir, which can be seen on Netflix, helped usher in a wave of discourse about the ills of the studio era – homophobia, misogyny and abuse among them – a topic that was revisited last year in Feud, the fictitious television recounting of the rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. And, just last month, JJ Abrams, Zachary Quinto, and Glaser announced they’d be producing a film called Tab & Tony, about the secret years-long dalliance between Hunter and Perkins.

Hunter, at any rate, preferred solitude and privacy to having his dirty laundry aired, the same way he preferred horses to humans. But there is a kind of poetic justice in that a man who spent much of his life in the shadows lived long enough to see his forbidden romance developed as a movie, one produced, as it ought to be, by two openly gay men.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion