The personal archive of Peter O’Toole, including bundles of letters, unpublished manuscripts, photographs and props, has been acquired by the University of Texas in Austin for $400,000.

O’Toole, who died aged 81 in 2013, was as well known for his hellraising and his enormous appetite for alcohol as he was for his memorable performances including his career-defining role in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.

The archive will allow a more textured appraisal revealing the man behind the character, said Eric Colleary, the curator of theatre and performing arts at the university’s Harry Ransom Center, which bought the collection.

“The personal nature of his archive reveals a more complex and nuanced individual who fiercely stood by his friends, who deeply cared for his family, who worried about his career and its direction, and who had an incredible curiosity about the world around him.”

Around 55 storage boxes of material shedding light on one of his generation’s most charismatic stage and screen actors will be made publicly accessible once it has been processed and catalogued.

The acquisition represents something of a coup for the university, given there is often fierce competition to acquire important cultural archives.

The actor’s daughter Kate O’Toole, who will be in Austin this weekend, said: “It is with great respect for the past and an eye to the future that I recognise the importance of making my father’s archive accessible and preserving it for future generations.

“Thanks to the nature of film, my father’s work has already been immortalised. The Ransom Center now provides a world-class home for the private thoughts, conversations, notes and stories that illuminate such a long and distinguished career.”

The archive includes small spiral bound notebooks that O’Toole – born, he said, in Connemara, but possibly Leeds – kept from his time as a cub reporter for the Yorkshire Evening News. There are also letters that shed light on his time at the Peter Hall-led Royal Shakespeare Company where he quickly became a star.

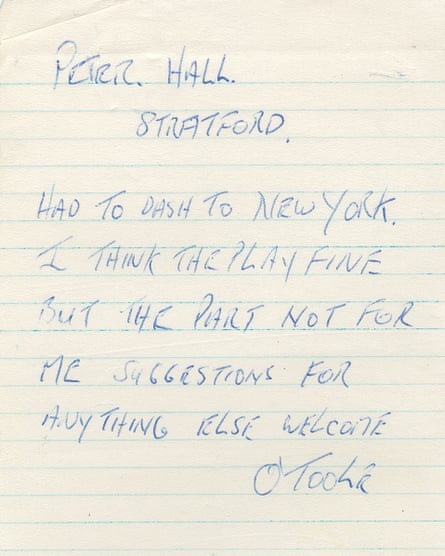

One, written on a sheet of notebook paper, reads: “Peter Hall. Stratford. Had to dash to New York. I think the play fine but the part not for me suggestions for anything else welcome. O’Toole.

It is a short, terse note which masks a deeper story since the part was as Henry II in Jean Anouilh’s Becket at London’s Aldwych theatre, a hugely important role he was expected and contracted to play. The reason O’Toole was going to New York was to be announced as the star of Lawrence of Arabia, the film that made him a superstar.

There are letters and contracts which relate to some of O’Toole’s most famous roles, including his Hamlet in 1963, the first production for Laurence Olivier’s new National Theatre.

A letter confirming O’Toole in the role offers him 30 guineas a performance, with a clause that the theatre retains the right to cancel if his filming of the movie version of Becket overruns.

That letter is part of the archive as is the sword with which O’Toole fought Derek Jacobi as Laertes in the play’s final scene, a sometimes terrifying experience given O’Toole was often well lubricated. “If he gave me a wink,” Jacobi has said, “and he usually did, this wild Irishman, it meant a very hard fight. It was even dangerous to be sitting in the front row when he flashed out his sword like Douglas Fairbanks.”

Another prop is from a far less successful production two decades later when O’Toole starred in Macbeth at the Old Vic, a production that had audiences laughing in all the wrong places and attracted some of the worst reviews anyone could remember.

Macbeth’s broadsword is part of the archive as are numerous letters about possible casting and stage design with O’Toole proposing an Irish designer whose business was inflatable sets.

Colleary said the archive provided compelling evidence of O’Toole’s abilities as a writer, with an unpublished screen adaptation of Uncle Vanya and chapters from what would have been his third memoir covering his career after drama school. “He was a brilliant writer, and his two published memoirs aside, this is an aspect of Peter O’Toole the world hasn’t yet seen.”

There are also letters to a roll call of the biggest names in acting including Marlon Brando, Vanessa Redgrave, John Gielgud, Katharine Hepburn, Dustin Hoffman, Paul Newman and Albert Finney.

O’Toole’s interest in theatre history is well represented, said Colleary, with examples of diligent research into his heroes, the 19th-century actors Edmund Kean and Henry Irving. “He saw himself as part of the genealogy of great actors and he wanted to understand what made their performances great.”

Other poignant items are a pair of Irving’s brown leather gloves that O’Toole had framed and hung at his Hampstead house; and the handwritten draft of his acceptance speech for when he received his honorary Oscar in 2003. He still holds the record – eight – for the most acting Oscar nominations without a win.

It is a rich archive, although there will be concern in some quarters that the archive is going to Texas and not to the British Library or the Bodleian, but Colleary argued that the Ransom Center offers “incredible context” given it has substantial holdings in the theatre and film sphere.

They include the archive of Tom Stoppard, who regularly watched O’Toole on stage at the Bristol Old Vic; the archive of Peter Glenville, who directed Becket; and the archives of actors including Edith Evans, Robert de Niro, Eli Wallach, Stella Adler and Anne Jackson. It also has strong holdings of Irving and Kean.