The first time professor Sherri Mason cut open a Great Lakes fish, she was alarmed at what she found. Synthetic fibers were everywhere. Under a microscope, they seemed to be “weaving themselves into the gastrointestinal tract”. Though she had been studying aquatic pollution around the Great Lakes for several years, Mason, who works for the State University of New York Fredonia, had never seen anything like it.

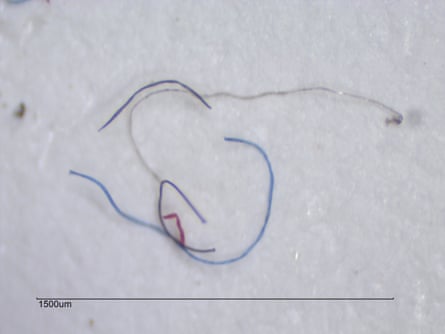

New studies indicate that the fibers in our clothes could be poisoning our waterways and food chain on a massive scale. Microfibers – tiny threads shed from fabric – have been found in abundance on shorelines where waste water is released.

Now researchers are trying to pinpoint where these plastic fibers are coming from.

In an alarming study released Monday, researchers at the University of California at Santa Barbara found that, on average, synthetic fleece jackets release 1.7 grams of microfibers each wash. It also found that older jackets shed almost twice as many fibers as new jackets. The study was funded by outdoor clothing manufacturer Patagonia, a certified B Corp that also offers grants for environmental work.

“These microfibers then travel to your local wastewater treatment plant, where up to 40% of them enter rivers, lakes and oceans,” according to findings published on the researchers’ website.

Synthetic microfibers are particularly dangerous because they have the potential to poison the food chain. The fibers’ size also allows them to be readily consumed by fish and other wildlife. These plastic fibers have the potential to bioaccumulate, concentrating toxins in the bodies of larger animals, higher up the food chain.

Microbeads, recently banned in the US, are a better-known variety of microplastic, but recent studies have found microfibers to be even more pervasive.

In a groundbreaking 2011 paper, Mark Browne, now a senior research associate at the University of New South Wales, Australia, found that microfibers made up 85% of human-made debris on shorelines around the world.

While Patagonia and other outdoor companies, like Polartec, use recycled plastic bottles as a way to conserve and reduce waste, this latest research indicates that the plastic might ultimately end up in the oceans anyway – and in a form that’s even more likely to cause problems.

Breaking a plastic bottle into millions of fibrous bits of plastic might prove to be worse than doing nothing at all.

Scary science

While the UCSB study is sure to make waves, researchers are consistently finding more and more evidence that microfibers are in many marine environments and in large quantities.

What’s more, the fibers are being found in fresh water as well. “This is not just a coastal or marine problem,” said Abigail Barrows, principal investigator of the Global Microplastics Initiative, part of the research group Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation.

Of the almost 2,000 aquatic samples Barrows has processed, about 90% of the debris was microfibers – both in freshwater and the ocean.

Microfibers are also the second most common type of debris in Lake Michigan, according to Sherri Mason’s research.

Finishing up research into tributaries of the Great Lakes, she’s finding that microfibers are the most common type of debris in those smaller bodies of water. “The majority [71%] of what we’re finding in the tributaries are actually fibers,” Mason said by email. “They exceed fragments and pellets.”

Mason is finding that the wildlife is indeed being affected.

A study out of the University of Exeter, in which crabs were given food contaminated with microfibers, found that they altered animals’ behavior. The crabs ate less food overall, suggesting stunted growth over time. The polypropylene was also broken down and transformed into smaller pieces, creating a greater surface area for chemical transmission. (Plastics leach chemicals such as Bisphenol A – BPA – as they degrade.)

Mason said her concern is not necessarily with the plastic fibers themselves, but with their ability to absorb persistent organic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and to concentrate them in animals’ tissues.

An increasingly toxic problem

Gregg Treinish, founder and executive director of Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation, which oversees Barrows’s microfibers work, said studies have led him to stop eating anything from the water.

“I don’t want to have eaten fish for 50 years and then say, ‘Oh, whoops’,” Treinish said.

His organization received $9,000 from Patagonia to research microfibers in 2016.

“It absolutely has the potential to move up the food chain,” said Chelsea Rochman, a postdoctoral fellow in conservation biology at the University of California at Davis and the University of Toronto. She cautioned, however, against a rush to avoid fish: “I think no one’s really asked questions directly about that yet.”

Rochman’s own recent study of seafood from California and Indonesia indicates that plastic fibers contaminate the food we eat.

Testing fish and shellfish from markets in both locations, Rochman determined that “all [human-made] debris recovered from fish in Indonesia was plastic, whereas [human-made] debris recovered from fish in the US was primarily fibers”.

Rochman said she can’t yet explain why fish in the US are filled with microfibers. She speculates that washing machines are less pervasive in Indonesia and synthetic, high performance fabrics, such as fleece, which are known to shed a lot of fibers, are not as common in Indonesia.

Industry reacts ... slowly

Companies that have built their businesses on the environment have been some of the first to pay attention to the growing microfiber issue. Patagonia proposed the Bren School study in 2015, after polyester, the primary component of outdoor fabrics like fleece, showed up as a major ocean pollutant.

Patagonia is part of a working group, as is Columbia Sportswear and 18 others, studying the issue through the Outdoor Industry Association (OIA), a trade group consisting of about 1,300 companies around the world.

“We believe the outdoor industry is likely one of those [industries that contribute to the microfiber issue], but we just don’t know the breadth,” said Beth Jenson, OIA’s director of corporate responsibility.

In an email, Patagonia spokesperson Tessa Byars wrote: “Patagonia is concerned about this issue and we’re taking concerted steps to figure out the impacts that our materials and products – at every step in their lifecycle – may have on the marine environment.”

Miriam Diamond, an earth sciences professor who runs the University of Toronto lab where Rochman now works, said she believes so-called fast fashion could play a larger role than the comparatively smaller outdoor apparel industry. “What I suspect is that some of the cheaper fabrics will more easily shed fibers. It’s probably that the fibers aren’t as long or that they aren’t spun as well,” Diamond said.

Inditex, which owns Zara and Massimo Duti among others, said microfibers fall into the category of issues covered by its Global Water Strategy, which includes ongoing plans to evaluate and improve wastewater management at its mills.

H&M declined to comment on the microfiber issue, as did Topshop , which responded by email “we are not quite ready to make an official statement on this issue”.

Time to take action

Mark Browne, the researcher responsible for first bringing microfibers to public attention, said that the grace period is over.

“We know that these are the most abundant forms of debris – that they are in the environment,” Brown said. He added that government and industry must be asked to explain “what they are going to be doing about it”.

The Amsterdam-based Plastic Soup Foundation, an ocean conservation project co-funded by the European Union, said better quality clothing or fabrics coated with an anti-shed treatment could help.

The foundation’s director, Maria Westerbos, said a nanoball that could be thrown into a washing machine to attract and capture plastic fibers also seems promising.

Another solution may lie with waterless washing machines, one of which is being developed by Colorado-based Tersus Solutions. Tersus, with funding from Patagonia, has developed a completely waterless washing machine in which textiles are washed in pressurized carbon dioxide.

Others suggest a filter on home washing machines. More than 4,500 fibers can be released per gram of clothing per wash, according to preliminary data from the Plastic Soup Foundation.

But the washing machine industry is not yet ready to act. Jill Notini, vice president of communications and marketing for the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers, said the washing machine could very well be a source of microfiber debris, but that the proposed solutions are impractical.

“How do you possibly retrofit all of the units that are in the market and then add a filter in and talk to consumers and say, ‘Here is a new thing that you’re going to have to do with your clothes washer?’”

She added that the industry still has trouble getting people to clean lint from the filters in their dryers.

For Plastic Soup’s Westerbos, the reluctance of the industries that operate in that crucial place between the consumer and the world’s waterways can no longer be tolerated.

“It’s really insulting that they say it’s not their problem,” Westerbos said. “It’s their problem, too. It’s everybody’s problem.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion