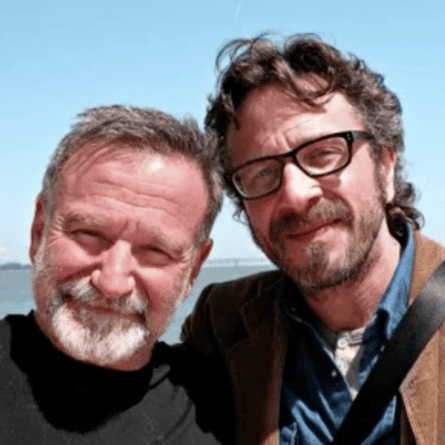

The night before I meet Marc Maron, I go to his standup show in London. These days Maron is best known for his hugely popular podcast, WTF with Marc Maron, which he started in 2009, and on which he has interviewed everyone from Barack Obama to Keith Richards and Chris Rock. He conducts most of the interviews from his garage in LA, and they are almost always revealing and always entertaining. In 2010, Robin Williams talked about his depression and addictions, four years before he killed himself. Obama talked about the racism and African American stereotypes that shaped his sense of self. WTF now gets 7m downloads a month.

But in the 90s, when I first discovered him, Maron was not known for his empathetic dialogues; rather, he was seen as an aggressive monologuer. Back then, he was a struggling standup, with a style that was often described as angry and arrogant – or, as his friend Louis CK once put it, “a huge amount of insecurity and craziness”. He was known as a comedian’s comedian, which is a nice way of saying the industry liked him, but audiences didn’t.

The man I see on stage in London is unrecognisable from those days. Once he struggled to sell tickets in comedy clubs; tonight he has sold out the 2,500-seat Royal Festival Hall, and his audience – mostly male thirty- and fortysomethings – cheer at his surrealist fantasies about Mike Pence, as well as more gentle stuff about how people used to find things out before the internet. For a man who has always claimed he doesn’t know what happiness is, Maron looks suspiciously like he might be enjoying himself. Some of this could be down to mellowing with age – he is, as he repeatedly mentions during his set, in his mid-50s – but it’s almost certainly more down to the validation of success.

After decades of resentfully watching his contemporaries, including CK, Sarah Silverman and Jon Stewart, soar to huge heights, Maron’s time has come; he is the overnight success 30 years in the making, the hot new thing at 54. He is currently appearing in Glow, Netflix’s extremely enjoyable feminist-ish drama about a women’s wrestling team, in which he plays the grizzled, cocaine-snorting TV director Sam. It’s his first starring role in a series that he hasn’t written (he played himself in his heavily autobiographical series Maron, which ended after four seasons) and he is absolutely terrific in it; there have been nominations for SAG and Critics’ Choice awards. He can convey both cynicism and regret in a single look, spitting out lines such as “I have a flaw in my conflict style, according to my ex-wife’s cognitive-behavioural therapist” with relish.

“Maron? He’s been reliably inconsistent throughout his career, but he’s on a bit of roll now,” he says on stage, imagining how his fans describe him to friends who have never heard of him. Once this schtick would have come across as bitter; now Maron just seems tickled.

The day after his show I meet him in a hotel room in central London. Maron often says that he tries to establish a “connection” with people on his podcast so, in order to establish a connection of my own, I tell him that we have a common acquaintance in New York. “Oh yeah, I know her real well. I don’t think she likes me that much,” he replies, not looking up from his phone. It seems worryingly as if he might be a guarded interviewee. Instead, it turns out that interviewing Maron is a lot like listening to his podcast: the emotional truths spill out fast.

Glow’s executive producers approached him to play Sam, and I ask if he thinks they saw connections between him and the character.

“Oh, sure, I certainly have an asshole that lives in me,” he says, looking up.

Actually, I meant the substance abuse and frequent references to divorce, I say. Maron often brings up his past relationships and addictions in his work, although he has been sober for a while now, having long given up his cocaine and bourbon habit.

“Yeah, yeah. I’m familiar with coke. I’m familiar with anger. I’m familiar with bullying. I’m familiar with selfishness. But at the core of all that I know that I’m a sensitive person, so I knew that would translate,” he says.

And it does: his performance as Sam, the irascible man who finds himself in charge of a team of women, is reminiscent of Tom Hanks’s similar role in A League Of Their Own. But Maron brings more darkness to the role, more anger. He bites out the words “my ex-wife” on the show with especial savagery.

“Well, you know, my second divorce was probably the most devastating thing I ever went through. I do have some closure around all that stuff, but I can get back into that place. You know, if you get someone talking about a divorce, especially if you’re a man who’s been screwed over by one, the angry passion just comes right back,” he says.

Maron has been married twice. The first marriage, in his early 30s, failed because “I was bad news – angry, druggie, drunk”; the second fell apart at least partly because he was needy after his then wife, writer Mishna Wolff, helped him get sober. “But the neediness was gnarled. You can’t ever say, ‘I need your support.’ You say, ‘You don’t love me.’ ‘Yes, I do.’ ‘No, you don’t.’ Then there’s fighting, crying, and then you’re like, ‘OK, you do love me,’” he says, with a rueful smile.

His bitter divorce from Wolff was the subject of his 2009 standup tour, Scorching The Earth, in which, among other things, he read out a snarky email he sent her (“It reveals him to be an embittered, petty man you think she was better off without,” one reviewer wrote). They are no longer in touch, because “she can’t stand me”, Maron says.

“I think that some of my behaviour was not great. It was emotionally abusive in some ways. But [there was] emotional turbulence between two people in a relationship, and I was an angry person – you’ve got to be allowed to have that. Someone copping to being out of line – I mean that’s only helpful to people, right?” he says.

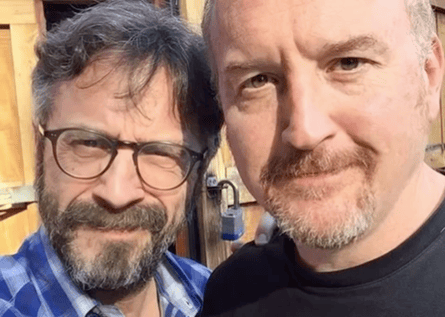

In his work, Maron is brutally honest about his foibles and sees this as mitigation. In one of the most celebrated episodes of WTF, Louis CK confronted Maron for having let his resentment of CK’s success get in the way of their friendship. Maron accepted this and apologised. Culture website Slate cited it as “the best podcast episode of all time”.

In November 2017, CK finally admitted to rumours he had long denied that he had masturbated in front of multiple women. Maron talked about it on his podcast, saying he’d asked CK about this in the past and that he’d denied it: “So I believed my friend.” Maron is also friends with the comedian Rebecca Corry, one of CK’s victims, but she hadn’t told him about it. Has he spoken to CK since his confession?

“No. I reached out to him, but I think he was out of town. I hope he’s doing OK. I don’t know what his life is like right now,” he says.

I ask if it has changed how he sees his friend, and he looks puzzled.

“I don’t know. I mean, you realise your friend has transgressed. But does it change how you see him? No.”

But he lied to you, and one of the victims is a friend.

“Yeah, yeah,” he says, and for the one and only time during our interview he seems uncertain of what to say. “I did not know about the extent [of CK’s harassment]. I mean, he did this horrible thing, he’s got a problem and he is paying the price for it. But what am I gonna do, not talk to him? Is that my place to do that, as somebody who has known him for ever? I don’t think so.”

I assume he’s said all he wants to say on the subject, and I start to move the conversation on, but he’s not done.

“I mean, outside of the global momentum around this [#MeToo movement], the outing of this stuff and taking people to task for it, these are individuals in my life. Yeah, I know Rebecca, so I’ve seen both sides and I feel bad for everybody,” he says.

CK’s downfall was shortly followed by that of Aziz Ansari, who has also appeared on Maron’s podcast; in January, he was accused of aggressive behaviour on a date. This story was less clearcut than CK’s, and while some saw it as an example of how complicated consent can be, others saw it as exploitative of Ansari.

“That Aziz thing was a little dubious and I think all of us [in the comedy community] felt that. It was sort of like, ‘We can’t go out with people any more?’ Women should be able to go to work and not be touched or see a dick or be hugged inappropriately or be manipulated sexually. Everyone’s got to figure out how to behave,” he says.

Maybe stories like this will help them figure it out, I say.

“Maybe. It just seemed off-message,” he says.

On his podcast, Maron has been excellent at calling comedians out for unacceptable behaviour. He has confronted people about joke-stealing and taken others to task for homophobia. So I wonder if he regrets any of his own past jokes. In 1999, he appeared on David Letterman and said he knew he was getting older when teenage girls stopped looking at him as a sexual being. “Don’t misunderstand: I’m not saying I want to have sex with teenage girls… I’m lying: of course I want to have sex with teenage girls. Come on, doesn’t everyone? That’s why there’s a law.” In 2014, he was interviewed on US TV and asked about his reputation for dating much younger women. “Yeah, resolving daddy issues since 1989. I’m here to help the young ladies,” he replied.

But when a male fan wrote to Maron recently to suggest that maybe he should take that Letterman clip down from his website, he was outraged.

“What am I, a personal totalitarian state? I’m going to have to start erasing my history? I don’t think it’s an inappropriate joke. I mean, the idea that men want to have sex with teenage girls – really, are you shocked? It says a lot that somebody – that a man – would reach out and say, ‘It’s not a good look to have that joke up.’ What is happening?” he asks.

Maron was born in New Jersey and grew up in New Mexico, the older of two sons of an orthopaedic surgeon and real estate broker. When Maron was a teenager, his father became emotionally fragile – “the crying, the sadness” – and these days has “a mania problem”. His parents divorced when Maron was in his 30s. When I ask about his mother, he folds his arms protectively.

“She’s always been strangely self-involved. I don’t feel like either of them were really capable of any kind of love,” he says.

Perhaps that’s why you never had kids, I say.

“Maybe. I’m an anxious person and the idea of taking on the anxiety of being responsible for another person is just horrendous to me,” he says.

When he went to Boston University, he stopped eating for what would be the first of several periods in his life. His mother once told him she didn’t know if she could love him if he was fat. He says she was delighted when she saw he had lost 20lb, even though he was “emaciated”.

“That’s the one thing that persists – the food stuff, which my mother gave me. I think it’s my deepest issue, more than the drugs. I don’t deny myself food any more, but I still beat myself up about it. I guess it’s about self-loathing and control,” he says.

And trying to make your mother love you?

“Oh, definitely, definitely.”

He began to rely on cocaine for confidence. I often think of cocaine as the drug for people who don’t have internal scaffolding, I say to him.

“Yeah, I think that’s true. It makes you feel built up. I used to sit at home with some whiskey, do a few lines of cocaine, and call my mother. I’d be like, ‘I’m doing gooood!’” he laughs.

Didn’t he worry that all that snorting fake coke on Glow would tempt him?

“Not really. I’ve had a pretty solid recovery. I just don’t want that any more. Like, coke? At this age? Who the fuck wants that? There’s a lot of practicality that’s found its way into my perception,” he says.

These days Maron is dating Sarah Cain, a 39-year-old artist, whom he references frequently and fondly. For a man who was so traumatised by his parents, he seems to have no fear of coupledom and monogamy.

“Yeah, I keep trying. A therapist once said to me that I’m seeking primal union, which I always liked the idea of.”

At times, Maron talks like a man who has spent a lot of time in therapy, and phrases such as “one of my therapists once told me” recur. He doesn’t so much wear his heart on his sleeve as his guts and gristle, too. But hanging out with him is never not interesting; he’s intelligent, candid and happy to talk about absolutely anything.

He says he handles his anger “better” these days, but glimpses of it are still visible. He is, he says, “hypersensitive to being diminished or not heard”, and so when his comedy career didn’t take off as quickly as that of his contemporaries, it felt almost unbearable. After his second divorce, when he was in his 40s, he considered killing himself in his garage.

“I just knew the life I was destined for was sad, and I didn’t know if I could hack it, being a relatively unknown [comedian], getting whatever venues I could,” he says.

Instead, he made the then extremely unusual decision to start a podcast, and in the same garage where he once contemplated suicide, interviewed President Obama a decade later. WTF began with conversations with his comedian friends, and he often spent most of the podcast apologising for having behaved so badly in the past. These days the interviews are a little more practised, although he generally connects better with men than with women. Few would have expected an insecure, resentful, former cokehead to be such an empathetic conversationalist, I tell him.

“Well, I had to get that side of me back! I get very connected [to people] when I meet them. It’s probably my lack of emotional boundaries,” he says.

One of the very few A-list comedians who hasn’t appeared on the podcast is Jon Stewart. Maron and Stewart’s mutual animosity is well known in the comedy world: what happened between them?

“Jon always represented to me why I was failing. I’m a smart Jewish guy, we’re about the same age, and yet… He’s very calculated, you know? He knew where he wanted to go and how to align himself, whereas I always saw agents and managers as the enemies – the suits. I had a lot of ‘fuck you’ in me. I come from that dumb rebel mindset. So when I’d see him [in the 90s and 00s], I’d act like he was personally destroying me,” he says.

As Maron floundered throughout the 90s, Stewart started getting TV slots, including a talkshow on MTV, and when he’d come to see Maron perform in comedy clubs, Maron would heckle him from the stage: “Oh, there he is, Jon Stewart from MTV. How does that feel, you sell-out fuck?”

Nonetheless, Stewart invited him to appear on his various pre-Daily Show TV programmes, and Maron would turn up and sneer, “Oh, so you’re the big shot, huh? Mr Big Guy?” Eventually, after years of this, Stewart got fed up and, backstage at an event, as Maron started in on him again, he said, “Why do you talk to me like this? I don’t need to take this from you any more,” and walked away.

Maron admits now he was “horrible” and “Jon didn’t deserve all that”, but his attempts to reconnect with Stewart have been rebuffed. Does he regret his behaviour? He laughs. “No, I don’t regret it! It was who I was.”

It’s a very Maron-esque story: self-deprecating and arrogant, apologetic and unregretful, pathetic and abrasive.

And then he remembers another thing one of his therapists once said, about how, ultimately, he’s always seeking to connect with people: “It’s not even an emotional thing, it’s a connection thing. And that’s not just with women, that’s with everybody.”

So that’s why he likes doing the interviews?

“Yeah, yeah,” he agrees. And then adds, as a caveat, “but when I get to know them – that’s when I become prickly and difficult.”

Glow returns to Netflix on 29 June.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion