Boeing on Monday fired its chief executive, Dennis Muilenburg, as the company battles to regain the trust of regulators, customers and the public after two crashes of its 737 Max plane claimed 346 lives.

In a statement, Boeing said the board had “decided that a change in leadership was necessary to restore confidence in the company moving forward as it works to repair relationships with regulators, customers, and all other stakeholders”.

The Chicago-based company said its chairman, David Calhoun, would take over as chief executive on 13 January. Muilenburg will leave Boeing with immediate effect, with chief financial officer, Greg Smith, serving as interim chief executive. Boeing did not respond to questions about how much Muilenburg will collect in severance pay.

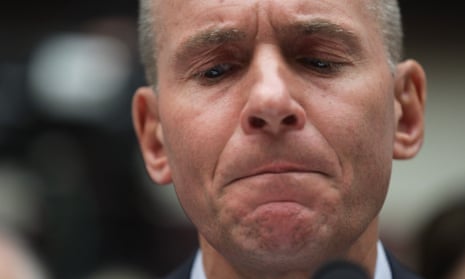

Muilenburg, 55, who has worked at Boeing for his entire 34-year career, has been widely criticised for failing to properly acknowledge the impact of the crashes on grieving families. He had also been accused of appearing to mislead the aviation regulator.

Boeing’s shares, which had slid 22% since the second crash in March 2019, jumped 2.7% to $336 after the announcement was made on Monday.

Indonesian Lion Air Flight 610 crashed into the Java Sea 12 minutes after takeoff on 29 October 2018 killing all 189 passengers and crew on board the 737 Max plane. On 10 March 2019 Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to Nairobi, Kenya, crashed six minutes after takeoff killing all 157 passengers and crew. That 737 Max plane was just three months old.

Boeing’s entire fleet of 737 Max planes has been grounded worldwide since the second crash.

The crashes have sparked numerous investigations, including a federal criminal investigation about the aircraft’s development and certification by the Federal Aviation Administration. Investigators suspect that a newly implemented automated flight control feature, the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), was a cause of the crashes.

The FAA found messages between two test pilots appearing to show that Boeing knew about problems with the 737 Max’s MCAS anti-stall system three years before the crashes. Some former Boeing employees questioned why Muilenburg didn’t ground the 737 Max after the first crash in October 2018.

More than a dozen relatives of Boeing 737 Max crash victims confronted Muilenburg during his testimony to US lawmakers in October to demand a personal apology.

Family members held up large photos of their lost loved ones from the gallery behind Muilenburg, who was addressing the Senate commerce committee about the crashes.

Nadia Milleron, the mother of Samya Stumo, killed in the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, confronted the former chief executive: “Mr Muilenburg, turn and look at people when you say you’re sorry.” He replied: “I’m sorry.”

“I wanted to let you know, on behalf of myself and all of the men and women of Boeing, how deeply sorry I am,” Muilenburg said in his formal address to the committee. “We made mistakes and got some things wrong.”

Earlier this month, Boeing said it would suspend production of the 737 Max early next year. The 737 Max was previously its bestselling plane, with 580 deliveries during 2018. Boeing’s overall deliveries have fallen by half during the first nine months of the year. It has nearly 4,500 planes on order, worth more than $500bn at list prices (each costs about $121m).

Boeing is the US’s largest manufacturing exporter and a shutdown would impact suppliers across the country, hitting an already troubled manufacturing sector. The suspension has already led to the cancellation of thousands of flights scheduled by airlines that were awaiting new planes or had bought ones that are now grounded.

Muilenburg, who has been chief executive since 2015, started at Boeing as an intern in 1985, rising through the company’s defence and services ranks. Before the crisis, Boeing shares had more than tripled during his tenure as the company boosted jetliner production and returned a bigger portion of profits to shareholders through stock buybacks and larger dividends.

Larry Kellner, who will take over the chairmanship, said: “On behalf of the entire board of directors, I am pleased that Dave [Calhoun] has agreed to lead Boeing at this critical juncture.

“Dave has deep industry experience and a proven track record of strong leadership and he recognises the challenges we must confront. The board and I look forward to working with him and the rest of the Boeing team to ensure that today marks a new way forward for our company.”

Calhoun said: “I strongly believe in the future of Boeing and the 737 Max. I am honoured to lead this great company and the 150,000 dedicated employees who are working hard to create the future of aviation.”

Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, said: “The CEO just seemed to be insufficiently responsive to deep public concerns about why Boeing failed to do more to insure the safety of the 737 Max, especially after reports that pilots were having difficulty controlling the MCAS system and then the first crash of the Lion Air plane.”