The hoopla around the launch of Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments is more reminiscent of the unveiling of an iPhone or something Pokémon-related than that of a mere book. On the evening of 9 September, 400 people will gather outside the doors of Waterstones’ Piccadilly store in London for the midnight release of the sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, her dystopian novel-turned-feminist touchstone-turned-meme-machine.

Fans, invited to dress up in the regulation ankle-length cloaks and bonnets worn by the handmaids in Atwood’s fundamentalist republic of Gilead, will snake round the block waiting for what Waterstones is calling a “one-night festival” of, immersive theatre, political speeches and themed cocktails. At 8.15pm doors will open to a four-storey Gileadean Glastonbury, featuring guest appearances from actor Romola Garai, activist Caroline Criado-Perez, Guilty Feminist podcaster Deborah Frances-White, plus a discussion of Atwood’s legacy with authors Jeanette Winterson, Elif Shafak, Neil Gaiman and AM Homes.

It’s an inventive, slightly surreal programme of events that – like Atwood – is a bit political, a bit geeky, a bit cerebral and unapologetically big on silly hats. It’s the ultimate hashtaggable celebration of a novelist who in the sixth decade of her career, having written more than 50 books of fiction, poetry and criticism, has mastered both Twitter (1.9 million followers) and Instagram (82,300). You know a writer has become a global phenomenon when the support act for their launch event includes two rivals for this year’s Booker prize. Winterson and Shafak’s novels were both longlisted, along with The Testaments, back in July.

At 11pm on the night of the launch, the tiny, sprite-like 79-year-old Canadian author will emerge to read the first extracts of a 432-page book that has been kept under the tightest of wraps. Only her closest associates have glimpsed the manuscript – apart from the Booker judges, who have described it as a “terrifying and exhilarating” follow-up to her 1985 novel. Publisher Liz Calder, who was one of Atwood’s longest-standing editors, is on this year’s judging panel. While she’s not allowed to reveal anything about the book’s content, she will say: “It represents not the work of a writer who might be at the end of her career but it’s like her peak, it’s amazing in that sense.”

All we know is that The Testaments is set 15 years after the final scene in the first book, in which narrator Offred is hauled into a van by heavies, who might be from the resistance or the regime that extinguished so many of the human freedoms we take for granted. When Atwood leaves the stage at midnight, fans will finally lay their hands on a book many have waited 34 years to read.

Atwood’s books have sold millions. She has won the Booker, for The Blind Assassin in 2000, and had five other novels shortlisted. She has yet to be given the Nobel prize for literature but that is widely seen as an error to be righted. When an embarrassed Kazuo Ishiguro was honoured with the award in 2017, he apologised to the Canadian writer: “I always thought it would be Margaret Atwood very soon; and I still think that, I still hope that.”

While she has been prolific throughout her career, there is little doubt that the Emmy award-winning TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale has helped make Atwood a superstar. It has connected the novelist to a vast new audience fascinated by her vivid nightmare of an America in ecological meltdown and a totalitarian regime that is systematically stripping women of hard-won rights, leaving many as little more than walking wombs. The timing has been crucial. Since the election of President Trump, the novel’s depiction of misogyny and witch-hunts feel chillingly prophetic and the red-cloaked handmaids have become an international symbol of women’s resistance.

But even before these developments, the novel had become a modern classic, translated into more than 40 languages, studied in schools and adapted into a film, an opera, a ballet and a graphic novel. “I’m a serious writer,” Atwood once said. “I never expected to become a popular one.”

“She couldn’t have seen that The Handmaid’s Tale would do what it did,” Winterson says. “She’s just got on with her work right from the beginning and allowed all this success to happen. But The Testaments has come at the right moment for her as well as us because she’s now a real sage.”

Sage she may be but this level of ceremony, cosplay and cult worship – involving no fewer than 120 Waterstones branches – is usually reserved for long-dead authors or Harry Potter. Certainly, the craft sessions and costume competitions celebrating her new novel seem a little kitsch, especially for a writer who delivers such apocalyptic prophecies about environmental havoc, predatory capitalism and overnight assaults on human rights. However, Atwood wouldn’t necessarily see the contradiction:

“She always takes herself seriously, but she has a great respect for play and inventiveness,” says her agent, Karolina Sutton. She recalls an occasion three years ago when she accompanied Atwood to the basement of a King’s Cross pub for the Kitschies, awards that celebrate speculative fiction. The prize was a knitted octopus tentacle, so Atwood insisted they wear homemade orange molluscs on their heads. “That’s what’s unusual about her, to have someone so intellectual who is so playful.”

Still, when you’re reading about totalitarianism in The Handmaid’s Tale or man-eating mutants in the Oryx and Crake trilogy or child sexbots in her 2015 novel, The Heart Goes Last, you may relish her wit and verve, but you never lose the eerie feeling that each feature of her dystopias might soon materialise in our own society – if they haven’t already. In recent years, Atwood has been hailed a prophet for creating stories about climate disaster, lab-manufactured meat, the western fertility crisis and human organs grown inside pigs, as well as societies increasingly ruled by misogynistic strongmen, years before they were on most people’s radar.

“She’s always before her time. Each novel is about something people become incredibly interested in half an hour later,” says Carmen Callil, founder of Virago Press, the publisher of books by women, who back in the mid-1970s was the first to bring Atwood’s work to a UK readership. When she first met the author over a lunch at Mon Plaisir in Covent Garden, she says she found her so “ferociously clever” that she “exploded my mind”.

Atwood is a writer with many gears; she can turn out transfixing character studies of Victorian women, poetry about sex between snails, essays on the history of debt and apocalyptic stories about bioengineering. Many novelists only dare to write about technology once it enters the mainstream, but she is interested in it from its inception – and rarely does it feel heavy-handed because it’s never been a chore for her to explore science in her fiction. It’s a quick hop from organ harvesting to sexual intimacy to high farce.

Callil says: “There is this tradition of women’s writing that uses irony and lightness of touch to deliver monstrous concepts and beliefs. It’s that ironic voice that has helped her seamlessly move from one generation of reader to the next. That is the test of a great writer.”

The Handmaid’s Tale remains Atwood’s most protean novel, with so much to say about how quickly and easily democracy can be dismantled. It remains one of the finest novels ever written on the relationship between sex, power and the social position of women. The novelist Valerie Martin, who was the first person to read it in manuscript, predicted a hit: “I told her: ‘You’re going to be very rich,’” Martin says. “Usually you read speculative fiction and squirm when sex comes up but she really gets how dangerous it is.”

Lennie Goodings, publisher of Virago Press, who has known Atwood since the late 1970s, agrees. “I love the sexual politics of her books. She gets sex and I think it’s because she understands power. She’s not a moralising writer but she’s a great observer and very honest. When you read her, you feel enlarged as a human being.”

Many novelists have written warnings about a future that come to seem eerily prescient. But Atwood is rare in that she has been around long enough to see systems come and go, witness various waves of feminism – and the reactions against them – and managed to respond in a second book. Such longevity, and depth of experience, is a surely a new experience for a writer.

Born in 1939, a few months after the outbreak of the second world war, Atwood spent much of her early years in the wilds of Canada, where her father, Carl, an entomologist, was studying leaf-eating insects. Her childhood was unusual. Her mother, also called Margaret, was a dietician who liked being in the wilds so she didn’t have to do housework. There was no mains electricity and few roads. Atwood – known as Peggy to her family and close friends – and her older brother, Harold (her sister, Ruth, was born later, in 1951), were schooled at home with textbooks that their mother obtained. If they worked through enough pages, they were left to their own devices.

This isolated childhood in the wilderness made Atwood fearless and pragmatic. Martin describes how when the family were staying on an island, the writer and her brother “dug a hole for an outhouse and nobody told them to stop so they dug this really, really deep hole. It’s still there, I believe, one of the wonders of the family. She knows how to get along without anything and if you have that knowledge, it makes you not care so much about unimportant things.”

If the weather was bad, the Atwood children would read Greek myths, Robinson Crusoe and HG Wells or re-enact the Battle of Waterloo with stuffed toys (Atwood is still a keen student of military history). One game with her bunnies inspired her to create a world of superheroes who inhabited a place called “Mischiefland”. Along with Harold, she wrote her own comics, often about space travel. But it wasn’t until she was 16 that the notion of writing for a living occurred to her. “[A] large invisible thumb descended from the sky and pressed down on the top of my head. A poem formed,” is how she described it. After studying at the University of Toronto, and then in Harvard, she wrote her first novel, The Edible Woman, published in 1969.

By then, she had married the writer Jim Polk, a relationship that ended in divorce in 1973. Shortly after, she became involved with novelist and ecological campaigner Graeme Gibson. The couple, who live in Toronto, have been devoted to each other ever since and have one daughter, Jess, born in 1976 and now an art historian who lives in Brooklyn with Atwood’s grandson.

Gibson has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and also suffers problems with his legs – but friends say he still travels with Atwood. The couple are used to an itinerant lifestyle, often spending several months a year in Norwich (where Atwood writes in local bookshop cafes). Earlier this year, they went on a boat around Australia and New Zealand. However, Gibson’s health may mean Atwood has to reduce the amount of travel she undertakes. “She’s being very brave about it and so is their daughter, Jess,” Martin says. “They’re going to figure out how to deal with it as they go along.”

One senses Atwood wants to seize every opportunity for fun. She delights in playing the mischievous granny, dispensing eldritch predictions. During a recent appearance at the Moon festival in Greenwich – one of many eccentric grassroots events she supports – she stood in front of a packed-out theatre and sang the opening of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana before performing bird calls. Bets are on as to whether she will break into song or cast a spell when she appears at the National Theatre, the night after the midnight launch, to discuss The Testaments for the first time.

At the event, which will be livestreamed to more than 1,500 cinemas worldwide, BBC broadcaster Samira Ahmed will chair a Q&A session with fans who have tweeted their questions to #askatwood, and actors (including Lily James) will read extracts from the book. Tickets sold out in a day, though 500 UK cinemas will be screening the event, which the organisers claim is comparable to the popularity of a Marvel movie. Atwood may be two months shy of her 80th birthday, but her star is still on the rise, a regular fixture at red-carpet events and in women’s fashion magazines.

Martin believes that now that The Handmaid’s Tale has entered popular mythology. “In some ways, the book has been spun away from her,” she says. “Perhaps what’s happening with this new novel is that she’s pulling it back in.”

I ask how much control Atwood likes to have. “A lot…” Martin replies, drily, “although not consciously at all. It’s necessary to control things in her world. She pays attention and is very good at understanding market forces and what people respond to.”

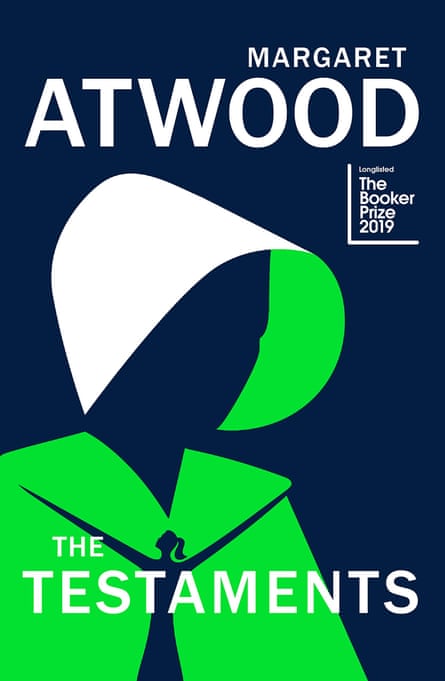

As a measure of her popularity, The Handmaid’s Tale is the most borrowed adult novel from London libraries, while Waterstones reports a 160% sales increase across all Atwood titles since the title of The Testaments was revealed. By coincidence, fashion chain Whistles’s autumn womenswear collection is dominated by the same navy blue and lime green colour scheme as Noma Bar’s eye-popping jacket design for The Testaments. Over the coming weeks, it won’t be unusual to see murals of handmaids on bookshop walls or teams of booksellers parading through city centres with placards reading “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum”, a feminist rallying cry from the book which roughly translates as “Don’t let the bastards grind you down”.

Such is the iron-clad security around the sequel that predicting its content is a little like writing a horoscope. Atwood has dropped a few breadcrumbs here and there. “Everything you’ve ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book,” she has said. “Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in.”

“All I know is that it’s three parts and [with] three different voices that are not in The Handmaid’s Tale, so it’s expanding it,” says Martin. Whether or not that’s true, the fact there are three narrators would suggest that Offred has been sidelined, perhaps in favour of the Marthas, the lower caste of women who wear green cloaks. Equally, the green of the cover could represent nature and the environment. Some Atwood fans believe the novel will focus on the climate crisis – especially its impact on women – since that is what she is preoccupied by these days. Winterson says she would be surprised if The Testaments wasn’t an environmentalist story.

“That’s part of what The Handmaid’s Tale is about,” Winterson says. “How would we respond to the issue? And we probably will respond in a totalitarian way. When the first big smash hits the west, I’m sure martial law will be introduced. Given that the west has moved so sharply to the right, I can’t imagine it won’t be an excuse for those powers to shut down all the things that have worried them so far. Just as it is at the beginning of The Handmaid’s Tale, when none of the women can get money out of their bank accounts any more.”

Novelist Naomi Alderman echoes the point. Atwood mentored Alderman for a year while she developed the concept for her bestselling novel The Power, a sci-fi story about what happens when teenage girls discover they have the power to electrocute others. The part of The Handmaid’s Tale that still unnerves her most is when women are robbed of their financial independence: “How simply it happens, how easily, how convincingly. Just cut off all women’s credit cards and bank cards. Just declare it illegal to employ a woman,” says Alderman. “It’s something that could happen to all of us, without any new technology needing to be invented. All it would take would be a bad government, a war, a stolen election. That possibility is never going away.”

Nevertheless, when it comes to the current gender wars, Atwood refuses to stick to a feminist script. She has faced a backlash for calling for due process for a University of British Columbia professor who was accused of sexual misconduct last year. But she has always expressed ambivalence about the feminist tag.

Goodings says there is nothing “sloppy” or “sentimental” about her view of women: “She is so much about equality but one thing she always says is that if women are going to be equal to men, we must also see that they do bad things too. There was a school of feminism that felt sisterhood was everything and that if women ruled the world, it would be entirely different, but she doesn’t have much truck with that. She’s pro-women but she doesn’t want to whitewash the truth.”

Friends point out that if you read Atwood’s fiction carefully, it cuts to the heart of how cruel and corrupt women can be. In The Handmaid’s Tale, we get Offred’s memories of her childhood with her mother, who was a 1970s feminist. She has a phrase about how men are just God’s way of making more women – and winds up burning books. Goodings says: “If you are a woman, you certainly know how horrible women can be. She faces up to it in The Robber Bride [1993]. There was a nasty woman who stole other people’s husbands. You look at Cat’s Eye [a novel about female bullying published in 1988], which is all about what little girls do to other little girls. When we published that, people were astonished. The reviews said it was Lord of the Flies for girls. The men I know were staggered by that book!”

Martin says Atwood isn’t necessarily comfortable with the idea of being a famous feminist. “It’s sad how some people absorb what they find in her work on such a banal level,” she says. “People who dress in costumes and go stand around the street is sad to me. When she talks about power, she’s careful to make clear that the women are in power as well and what we’re talking about is human tendencies, not just male and female tendencies. But obviously the condition of women historically is of interest to her.”

Winterson believes Atwood is a “proper feminist” because she has helped champion so many other women – but can understand why she has resisted the term. “It’s the fear of being labelled, just as she resisted the science-fiction label and wanted to call it ‘speculative fiction’. Labels are annoying and usually they are limiting. I used to hate being called a gay writer because I knew damn well it was about patronising men trying to limit the scope of the work.”

“No one will influence her choices,” says Karolina Sutton. “She doesn’t chase trends, she’s not interested in following success. If there’s something that interests her about humanity she will write about it.” Sutton, an agent with many big-name authors on her roster, says she has never met anyone as “superhuman” as Atwood. “She’s ahead of everyone in the room… she doesn’t make mistakes. She’ll be asked to write a 3,000-word piece about a subject that’s just thrown at her – on plastics or the Russian revolution. If there’s a phone at hand, she will do it.”

Friends say she can be very tough. “I’ve seen her make strong women quail,” says Calder. But they all speak of her generosity. “She’s big-hearted,” Winterson says, “and the older I get, the more important I think that is, to be big-hearted towards life and not worry too much about your own position within it.” Atwood also likes a prank. Alderman says that the day after they first met, she tricked her into thinking she could speak Anglo-Saxon. “It seemed believable! Who was I to say? She got a good laugh out of that one.”

Atwood is reportedly in good health and has always been disciplined about her diet. Martin jokes that she is so productive – baking pies, hosting large dinners, knitting sweaters, signing books and lending support to charities and community campaigns – that she must have a secret double chained to a desk in a windowless room in Saskatchewan, maniacally typing her manuscripts. “I’ve spent a lot of time with her, days on end, and I never see her write!” Martin laughs. “I don’t get when she does it! I think she’s made out of space-age plastic or something.”

Calder, who was Atwood’s UK editor in the 1980s and 90s, notes that she constantly renews her working methods. She was the first person to use the story-sharing website Wattpad; she even invented, with her stepson, a remote book-signing device called the LongPen that allows her to sign books for fans all over the world. Calder also describes how one year, Atwood decided to overhaul the process by which her books were edited, having grown fed up with responding to different editors around the world: she called a summit. “We all trooped to Toronto where she presented us each with the new manuscript which was beautifully tied up with a blue bow. We read solidly for two days without consultation and we didn’t discuss it until we had to put our suggestions to her – it was immensely practical.”

The “summits” continue to this day, and often conclude with a snowy walk to her house for supper. In January, a smaller group flew to Toronto, where it was minus 20C, to discuss The Testaments. Sutton says: “It’s an editorial process like no other and she makes it very special for everyone. There’s always more theatre, it’s more creative. But no one can dictate to Margaret Atwood! She will say: ‘Well, everyone wants it to be a different book but it is my book and it is what it is.’”

Atwood might joke that “all the books are compensation for being short” but she’s rarely self-deprecating. Goodings says she’s not embarrassed by her power. “She wields it cleverly, I think. She’s still very ambitious.” Without her, the end of the world wouldn’t be half so entertaining.

The Testaments is published by Vintage (£20). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846

Read an exclusive extract from The Testaments by Margaret Atwood in next Saturday’s Guardian Review

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion