As you enter Roman Road gallery in London’s East End, the noise from a pair of speakers in the foyer is almost overwhelming: grunts, exhalations and the thud of heavy metal weights landing on the floor. Recorded in a bodybuilder’s gym, this is an introductory soundscape for Alix Marie’s show, Shredded.

“I want the viewer to enter an environment that is immediately uncomfortable, almost scary,” says the Paris-born artist, whose work merges photography and sculpture and tends towards the grotesque. “I have amplified what the novelist Kathy Acker, herself a bodybuilder, called ‘the language of the body’ as it undergoes this extreme transformation and essentially breaks down.”

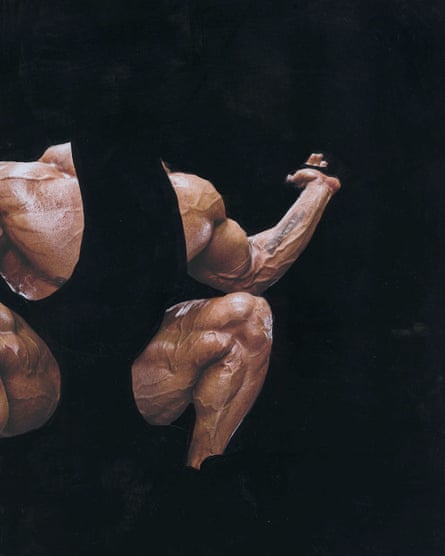

In the main gallery, the noise is different but no less relentless. Fans pump air into three inflatable polyester torsos – all bulging biceps, veiny skin and straining muscle – that stand erect and quivering on a raised shelf. As a metaphor for extreme bodybuilding, the pumped-up photo-sculptures are both disturbing and surreal. Likewise the images in the light boxes below, more close-ups of bulging bodies that seem to be sweating under bright spotlights. On closer inspection, they are mounted on shallow vitrines half-filled with liquid. On the opposite wall, cut-out silhouettes of pumped-up bodies are arranged in a row – arms, chests and necks, thighs as big as tree trunks. The combined effect of the noise and image overload in such a confined space is claustrophobic, ultra-masculine, almost intimidating. But also oddly camp.

“Good,” says Alix Marie, laughing. “Bodybuilding is a performance of extreme virility but, in competition, it also comprises huge men almost naked except for tight gold pants. For me, the contrast of the machismo and the campness is fascinating. When they perform they become moving sculptures, as much Auguste Rodin as Arnie Schwarzenegger.”

It was the young Arnie who, in the 1977 documentary Pumping Iron, famously likened the ritual of professional bodybuilding to having sex with a woman: “I am coming day and night. It’s terrific, right … I’m in heaven.” For Alix Marie the fascination was more about the ways in which masculinity is exhibited and performed in extremis in an enclosed, all male world. The bodies that feature in her exhibition belong to three men she photographed in gyms in Bethnal Green, Ealing and Tottenham. “I used to live opposite the one in Tottenham,” she says, “After some persuasion, they let me in to their boxing room for a total of five minutes to shoot the model. I guess they didn’t want to freak out the clientele with a female presence.”

Shredded – the term describes someone with extremely low body fat and very well defined muscles – continues Marie’s interest in “body, gender and sculpture.” In the past, she has cast her own body parts in grey concrete and printed the images on glass, fabric, paper-mache and PVC. For one show, she draped images of nude torsos on metal scaffolding and, for another, plastic pipes of fluids snaked along the gallery floor, erupting out of sculptures that looked like mutant sexual organs straight out of a David Cronenberg movie. She cites the aberrant film-maker as a prime influence alongside the surrealists. Her most powerfully unsettling work seems to come from a similar source – the realm of the unconscious and irrational, but it is tempered with a consistent formal discipline and a desire to somehow meld two creative practices that do not tend to sit together easily.

“It is challenging to work with photography as sculpture, but it is what has always fascinated me,” she says, “I never wanted to chose between the eye and the hand. In a way, I want to go inside the photograph, which is, of course, impossible. Also, I need physical contact in the making of the work, but as a big part of the viewer’s experience of it.”

A small survey of Marie’s work was on show earlier this month at Photo London. It included a ceramic sculpture in which an image of a human eye was continuously drenched in absinthe from a perspex fountain. (The tableau refers to a French wedding night tradition in which the groom places an icon of an eye in a bidet used by the bride.) Visitors could kneel and drink from the absinthe fountain if they so wished. In the context of her recent work, it was a user-friendly piece. Across town, in a group show called Apparatus, at Peckham 24, things were more brutally physical with outsize inflated polystyrene sculptures of muscular arms rotating on a contraption that called to mind a kebab skewer. “I like the idea of the viewer being simultaneously fascinated and repulsed,” she says. “The environments I create are often uncomfortable. They demand a reaction.”

Alix Marie is part of a generation of young mostly female photographers, including Juno Calypso and Maisie Cousins, whose work explores notions of femininity, eroticism, gender and body image. In contrast to the uninhibited physicality of Cousins’s more sensual close-ups of brightly-lit, glistening bodies, lips and tongues, Marie’s work is often defined by her interest in the grotesque. Fluids, flesh-coloured tubing and rubber sculptures that resemble mutant sex aids have all featured in her work. She cites the transgressive writings of Georges Bataille as another abiding influence alongside the still-shocking fetishistic doll sculptures of Hans Bellmer. “As a feminist,” she muses, “I have to ask myself why is he one of my favourite artists?”

French film, too, is a touchstone. At Photo London, an image printed on fabric of male hands buried in female hair rippled just above ground level in the artificial breeze created by a hidden fan. It could have been taken from a French nouvelle vague movie.

“I was raised watching a film a day,” she says of her childhood in Paris. Born in 1989, to a screenwriter mother and a father who was a film theorist, historian and lecturer. “They really don’t get what I do, but they are hugely supportive,” she says.

Alix Marie has lived in London for 11 years, studying fine art at Central Saint Martins before completing an MA in photography at the Royal College of Art. She says: “One of the things that most interests me is the clinical aspect of analogue photography that somehow links it to medicine – the technicians, the laboratory, the baths, the gloves, the scalpel. For me, it is essentially a laboratory process and I approach it as such, as a place of experimentation and exploration.”

What has she learned from her immersion in the world of extreme bodybuilding? “I don’t think I have ever been in a more self-conscious environment,” she says. “It’s about looking strong, about poise and pose. Being ripped, as they call it, is increasingly popular, but the bodybuilders still feel they are treated like freaks. It is a very enclosed world.” She pauses for a moment, “I would describe it as being very formal, very repetitive, an activity that lies between science and art.” She breaks into laughter. “Then again, I could just as easily be talking about photography.”