The Victorian Anti-Vaccination Movement

Today's anti-vaccination movement is not the first. Riots, pamphlets, and an outcry in 19th-century England set the stage for contemporary misinformation campaigns.

The dewy chill over Leicester, England, in March 1885 did not deter thousands of protesters from gathering outside nearby York Castle to protest the imprisonment of seven activists. Organizers claimed as many as 100,000 people attended, although historians estimate it was closer to 20,000.

The cause they rallied against? Vaccination.

This movement has faded from popular memory, obscured by the controversy of more recent anti-vaccination efforts, which gained momentum in the 1990s. However, the effects of the Victorian anti-vaccination movement still echo in the debate over the personal belief exemption, which was banned in California in June.

On the day the Leicester protesters gathered, vaccination was mandatory in England. Nearly a century before, Edward Jenner, a Scottish physician, had invented a method of protecting people against the raging threat of smallpox. The treatment was called variolation, and it involved voluntary infection with a similar disease. Patients were given cowpox to protect them against the much deadlier smallpox, much the way parents long exposed their children to chicken pox to protect them from getting sicker from the illness later in life. (Today pediatricians recommend the chicken pox vaccine instead.)

After germ theory was expanded upon and researchers developed vaccines, the British government outlawed variolation, which still carried some risk of killing the person it was meant to protect, in the Vaccination Act of 1840. Safer vaccines, which contain a weakened form of a particular disease, replaced variolation, which was a controlled exposure to a disease by injecting a healthy person with some of the infected pus or fluid of an ill person. To encourage widespread vaccination, the law made it compulsory for infants during their first three months of life and then extended the age to children up to 14 years old in 1867, imposing fines on those who did not comply. At first, many local authorities did not enforce the fines, but by 1871, the law was changed to punish officials if they did not enforce the requirement. The working class was outraged at the imposition of fines. Activists raised an outcry, claiming the government was infringing on citizens’ private affairs and decisions.

Over the course of a decade, multiple prominent scientists threw their support behind the anti-vaccination movement as well.

“Every day the vaccination laws remain in force parents are being punished, infants are being killed,” wrote Alfred Russel Wallace, a prominent scientist and natural selection theorist, in a vitriolic monograph against mandatory vaccination in 1898. He accused doctors and politicians of pushing for vaccination based on personal interest without being sure that the vaccinations were safe. Wallace cited statistics from a report by the Registrar-General of deaths from vaccination from 1881 to 1895, showing that an average of 52 individuals a year died from cowpox or other complications after vaccination. Wallace pointed to the deaths to assert that vaccination was useless and caused unnecessary deaths.

Pro-vaccinationists cited other statistics from London, where the number of deaths from smallpox fell significantly between the 18th and 19th centuries, after the discovery of vaccination. The National Vaccine Establishment figures claiming that nearly 4,000 people died in the city each year from smallpox before the discovery of vaccination, which Wallace and other anti-vaxers claimed was a grossly inflated figure. The Statistical Society of London noted in its journal in 1852 that “smallpox has greatly prevailed,” saying that vaccination was insufficient but that the registrars of the various counties were optimistic that it could work in the future. British government chose not to answer, staying silent behind the law as protests mounted.

Epidemic disease was a fact of life at the time. Smallpox claimed more than 400,000 lives per year throughout the 19th century, according to the World Health Organization. Nadja Durbach, a professor of history at the University of Utah and the author of Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853-1907, says a major difference between the 19th century movement and today’s is that anti-vaxers in the past were more aware of the consequences of their choice: Disease was still rampant. Despite the existence of vaccines, thousands still died of infectious disease every year. Today, in most developed countries, large-scale epidemics are confined to the annals of history or to flash-in-the-pan flare-ups such as MERS in South Korea.

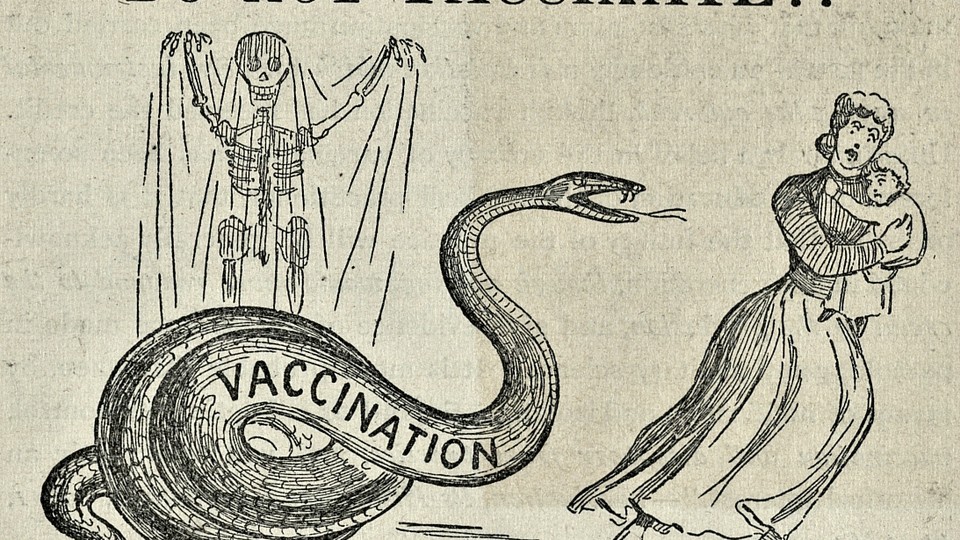

By the time of the Leicester protest, public opinion was souring toward vaccination. The injections were not completely without risk, with a percentage of those who received the vaccination becoming ill, and riots broke out in towns such as Ipswich, Henley, and Mitford, according to a 2002 paper in the British Medical Journal. The Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League launched in London in 1867 amid the publication of multiple journals that produced anti-vaccination propaganda. Another chapter cropped up later in the century in New York City to spread the “warning” about vaccines to the United States.

Under this pressure, the British government introduced a key concept in 1898: A “conscientious objector” exemption. The clause allowed parents to opt out of compulsory vaccination as long as they acknowledged they understood the choice. Similar to today’s religious exemptions in 47 U.S. states and the personal belief exemptions in 18 states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, the parents signed paperwork certifying that they knew and accepted the risks associated with not vaccinating.

Modern vaccination activists come from a different world than those in the 19th century. While anti-vaxers today are largely upper middle class, the crowd opposing vaccination in the 19th century was largely composed of lower- and working-class British citizens, according to Durbach.

“They felt that they were the particular targets, as a class group, for vaccination and for prosecution under the compulsory laws,” she says. “This was part of a larger expression of their sense of themselves as second-class citizens who thus lacked control over their bodies in the way that the middle and upper classes did not.”

By the close of the 19th century and the dawn of the 20th, the protests had come to a head. The anti-vaccination sentiment had spread to the U.S., garnering support in urban centers such as New York City and Boston.

The British government ceded its stringent line to the protests of the people. The law was amended yet again in 1907 to make the exemptions easier to obtain—because of an extensive approval process, many parents could not obtain the necessary paperwork to claim the exemption before the child was more than four months old, past the deadline.

The U.S. government, however, took a harder tack. In the 1905 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the court upheld the state government’s right to mandate vaccination. The Massachusetts Anti-Compulsory Vaccination Society lobbied hard for the court to rule in favor of the plaintiff, but all they won from the decision was the provision that individuals cannot be forcibly vaccinated.

The protests quieted after these two decisions, but small pockets of unease have now bubbled up again. Durbach said that unless the root issues are addressed—the boundaries of personal freedom versus social obligations—the movement will continue to resurface with different faces.

“The argument about personal freedom is important,” Durbach says, “but we willingly surrender these freedoms when we believe it is for the public good and our own safety.”