You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1

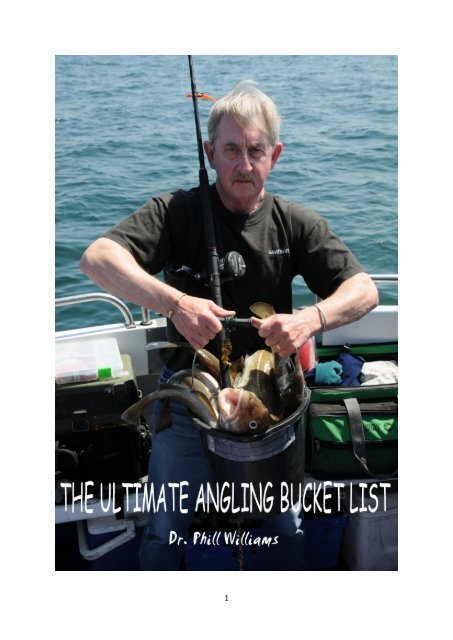

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>ULTIMATE</strong> <strong>ANGLING</strong><br />

<strong>BUCKET</strong> <strong>LIST</strong><br />

Dr. Phill Williams<br />

Copyright © 2016 by Dr. Phill Williams<br />

ISBN 978-0-9957216-1-6<br />

All Rights Reserved<br />

To be born a fisherman is to win first prize in the lottery of life<br />

2

<strong>THE</strong> ACTUAL <strong>BUCKET</strong> <strong>LIST</strong><br />

100 species of fish from British and Irish waters<br />

300 hundred species in total worldwide<br />

A 200 pound fish from my own trailed boat<br />

A 200 pound fish from the shore<br />

A 100 pound fish from freshwater<br />

A double figure trout<br />

A double figure bass<br />

Any fish in excess of 1000 pounds<br />

A British record fish<br />

A European record fish<br />

A World record fish<br />

Write features for all the UK sea angling magazines<br />

Produce 200 archive audio angling interviews<br />

Complete a fishery based Ph. D research project<br />

Produce and publish this book<br />

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

I've been taking photographs of fish and fishing, often badly, for as far back as I can remember, and as<br />

a result, I have recorded a lot of angling history as well as different fish species.<br />

Unfortunately, many of what would obviously have been the best and therefore most important<br />

photographs have not survived, primarily because magazines often didn't extend the courtesy of<br />

returning transparencies, used or otherwise, in the days before digital cameras.<br />

To some extent, the knock from this is reflected in the illustration used here, of which I acknowledge<br />

there is rather a lot. In addition to the sheer volume, the range of coverage in terms of quality is another<br />

factor worth mentioning.<br />

This includes everything from high resolution digital images and old black and white shots through to<br />

scanned colour transparencies. Even occasionally, scanned newspaper clippings, and to fill in the gaps,<br />

a few pencil and ink sketches here and there which due to my RA problem were extremely difficult to<br />

do.<br />

I make no apology for all of this. To my way of thinking, this range and diversity in terms of age and<br />

quality actually contributes to the finished item as a historical piece, charting one anglers life-time<br />

progression from that first serious wetting of a line through to semi-retirement from fishing on medical<br />

grounds, with all the changes in technology and fortunes that have paralleled it along the way.<br />

In order to illustrate and support the text to the extent I wanted, I have had to turn to a number of angling<br />

friends, journalists, and other members of the angling community for help, which in all cases, and at<br />

times even from people I didn't previously know, has been freely given, and without whose generosity<br />

the finished item would most certainly have been much the poorer. So to the following people I owe a<br />

particular debt of gratitude.......<br />

Graeme Pullen: for photographs, accommodation, and many instances of good fishing both home and<br />

abroad over the years.<br />

Dave Lewis: as with Graeme, for photographs too numerous to mention individually, accommodation,<br />

and instances of good fishing both home and abroad.<br />

Mike Millman: West Country journalistic legend and copy right holder of so many amazing big fish<br />

pictures accumulated over that period of angling history when there were still plenty of big fish about,<br />

with excellent record prospects, and Devon and Cornwall sitting right at the epi-centre of it all.<br />

World Sea Fishing (WSF): Both Mike Thrussell Jnr and Snr for shots of wreckfish, john dory and<br />

gilthead bream.<br />

Bill Rushmer Anglers Mail: Not only for some beautiful shots of crucian carp, grass carp and golden<br />

orfe, but also for steering me in the direction of other missing photographs.<br />

Ron Greer and Alastair Thornes: Ferox 85 co-founders, for providing some of the ferox pictures and<br />

some excellent memories of some truly wild fish caught in truly wild conditions.<br />

Andy Griffith: for photographs of mako and porbeagle sharks in particular, plus others including black<br />

mouthed dogfish and albacore. blue shark, blue fin tuna and conger.<br />

Michael McVeigh: Irish charter skipper based near Downings and pioneer of blue fin tuna fishing who<br />

provided some of the tuna photographs, plus several other less common species such as megrim and<br />

cuckoo ray.<br />

4

Colin Penny: skipper of the Weymouth based charter boat 'Flamer IV' and the man behind many<br />

amazing catches and photographs including here, undulate rays, sunfish, axillary bream, and many of<br />

the smaller less commonly caught species such as red band fish.<br />

Keith Armishaw: my man at Angling Heritage who provided some of the freshwater photographs and<br />

his PB common skate.<br />

Mike Winrow: River Ribble barbel specialist and the man who introduced me to barbel fishing. Mike<br />

provided not only some of the barbel photographs, but also shots of big tench, bream and carp.<br />

Rob Rennie: Welsh charter skipper and shark specialist who provided the thresher shark picture.<br />

Mark Everard: who as you might expect from a specimen roach fanatic provided the roach photographs,<br />

plus some of the smaller freshwater species which for me were difficult to get in front of a camera lens,<br />

including the pumpkinseed.<br />

Warren Harrison: for photographs of his world record carp haul from Euro Aqua Lake which included<br />

fish of 87, 90 and 94 pounds.<br />

Alex Wilkie: Scottish fly fishing fanatic who attempts to catch everything in freshwater and at sea on<br />

the fly.<br />

Andy Bradbury: Fleetwood charter skipper who I often fish with and who helped out with pictures of<br />

scad, sole and mackerel.<br />

Paul Kirkpatrick: Whitby charter skipper who provided some of the cod and halibut photographs.<br />

Paul Maris: A man I have fished with on many occasions for tope and skate. A big fish specialist who<br />

provided the specimen conger picture, plus quite a bit to write about with regard to big fish.<br />

Kev McKie: Liverpool charter skipper who provided photographs of a number of unusual fish including<br />

the topknot.<br />

Jon Patten: Big fish specialist whose name appears under many enviable fish pictured throughout the<br />

book.<br />

Sean McSeveney: For the streaked gurnard photograph.<br />

Dean Lodge: Species Hunt App – for pointing me in the direction of some of his species photograph<br />

sources, and for providing the greater pipefish shot.<br />

Jonathan Law: Provider of pictures of butterfish, connemera sucker and other mini species.<br />

Adam Kirkby: Pictures of leopard spotted goby and bogue, plus setting me up for others with several<br />

of his Face Book friends.<br />

Andy Copeland: well known shore match angler, species hunter and LRF fanatic who baled me out<br />

with some of the rarer mini species.<br />

Sven Hille: German Baltic trolling expert who provided me with some excellent fishing, plus<br />

photographs of salmon, sea trout, pike and cod.<br />

Aram Taholakian: Owner of 'Gone Fishing' Fuerteventura where I walked in off the street to talk fishing<br />

and came away with shots of some of the rarest fish around.<br />

Tony Parry: Rhyl/Mersey charter skipper and friend who has provided much in many ways including a<br />

dragonet picture for this book.<br />

5

Greg Whitehouse: For taking thin lipped mullet fishing to another level and providing the photographic<br />

evidence, some of which is used here in the form of two record fish.<br />

Ken Robinson: Some interesting cod fishing sessions over the years and a photo of his Scottish shore<br />

record cod from Balcary.<br />

Shawn Kittridge: Photographs of rudd and gudgeon.<br />

Duncan Charman: Beautiful shot of brace of elusive 3 pound plus Silver Bream.<br />

Robin Howard: fishyrob.co.uk for his amazing grayling picture.<br />

Steve Perry: stingray and giant goby photographs.<br />

Alastair Wilson: Irish dinghy caught blue fin tuna photographs.<br />

Richard Torrens: Tanked photograph of bitterling.<br />

Eddie Weitzel: Sketch of the late great Les Moncreiff.<br />

FaceBook as a concept through which I spent many hours searching for suitable pictures and people to<br />

contact, some of whom contacted me when they realised the project was on.<br />

Philip Gill: Who not only prepared the working template along with giving guidance on its use, also put<br />

in a lot of time tidying up pictures and illustration, followed by an even longer time finally presenting<br />

the volume for website upload and free download.<br />

6

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Page<br />

The Actual Bucket List 3<br />

Acknowledgments 4<br />

Table of contents 7<br />

Introduction 16<br />

PART ONE – Home waters species<br />

The cartilaginous species<br />

Cartilaginous fish biology 18<br />

Mako Shark 24<br />

Porbeagle Shark 26<br />

Thresher Shark 31<br />

Blue Shark 33<br />

Six Gilled Shark 38<br />

Tope 40<br />

Common Smoothhound 47<br />

Starry Smoothhound 48<br />

Spurdog 51<br />

Bull Huss 54<br />

Lesser Spotted Dogfish 57<br />

Black Mouthed Dogfish 59<br />

Monkfish or Angel Shark 60<br />

Flapper Skate & Blue Skate 62<br />

Bottle Nosed Ray or White Skate 69<br />

Thornback Ray 72<br />

Small Eyed Ray 78<br />

Blonde Ray 80<br />

Spotted Ray 82<br />

Undulate Ray 84<br />

Cuckoo Ray 86<br />

7

Sandy Ray 87<br />

Sting Ray 88<br />

Eagle Ray 90<br />

Dark Electric Ray 91<br />

Marbled Electric Ray 92<br />

The bony fishes<br />

Bony fish introduction 93<br />

Introduction to Cod Family 93<br />

Cod 94<br />

Pollack 106<br />

Coalfish 110<br />

Haddock 112<br />

Whiting 115<br />

Blue Whiting 119<br />

Pouting 120<br />

Poor Cod 121<br />

Hake 122<br />

Ling 125<br />

Torsk 128<br />

Greater Forkbeard 129<br />

Tadpole Fish 129<br />

Three Bearded Rockling 130<br />

Four Bearded Rockling 131<br />

Five Bearded Rockling 132<br />

Shore Rockling 133<br />

Introduction to Flatfishes 133<br />

Plaice 136<br />

Dab 142<br />

Flounder 145<br />

Lemon Sole 149<br />

Witch 150<br />

Halibut 151<br />

8

Long Rough Dab 153<br />

Turbot 154<br />

Brill 159<br />

Megrim 163<br />

Common Topknot 164<br />

Sole 165<br />

Introduction to Bass Family 167<br />

Bass 168<br />

Comber 178<br />

Wreckfish or Stone Bass 179<br />

Dusky Perch 180<br />

Introduction to the Mullets 181<br />

Thick Lipped Grey Mullet 181<br />

Thin Lipped Grey Mullet 185<br />

Golden Grey Mullet 190<br />

Red Mullet 191<br />

Introductions to Mackerels & Tuna’s 192<br />

Blue Fin Tuna or Tunny 193<br />

Big Eyed Tuna 198<br />

Long Finned Tuna 199<br />

Pelamid 200<br />

Mackerel 201<br />

Chub Mackerel 204<br />

Introduction to the Jacks 205<br />

Scad 205<br />

Greater Amberjack 206<br />

Guinean Amberjack 208<br />

Almaco Jack 208<br />

Blue Runner 209<br />

Pilot Fish 210<br />

Introduction to the Sea Breams 210<br />

Black Bream 211<br />

9

Red Bream 217<br />

Gilthead Bream 220<br />

Couches Bream 222<br />

Bogue 223<br />

Pandora Bream 223<br />

White Bream 224<br />

Axillary Bream 225<br />

Saddled Bream 225<br />

Rays Bream 226<br />

Introduction to the Wrasses 227<br />

Ballan Wrasse 227<br />

Cuckoo Wrasse 233<br />

Corkwing Wrasse 234<br />

Goldsinny Wrasse 235<br />

Rock Cook Wrasse 236<br />

Scale Rayed Wrasse 236<br />

Baillon’s Wrasse 237<br />

Introduction to the Gurnards 238<br />

Tub Gurnard 238<br />

Red Gurnard 240<br />

Grey Gurnard 242<br />

Streaked Gurnard 242<br />

Introduction to the Garfishes & Skippers 243<br />

Garfish 243<br />

Short Beaked Garfish 245<br />

Skipper 245<br />

Introduction to the Herrings 246<br />

Herring 246<br />

Pilchard 247<br />

Anchovy 248<br />

Twaite Shad 248<br />

Allis Shad 250<br />

10

Introduction to the Gobies 251<br />

Black Goby 251<br />

Common Goby 252<br />

Rock Goby 252<br />

Sand Goby 253<br />

Giant Goby 253<br />

Leopard Spotted Goby 254<br />

Introduction to the Blennies 254<br />

Tompot Blenny 255<br />

Shanny 255<br />

Butterfly Blenny 256<br />

Black Faced Blenny 257<br />

Yarrell’s Blenny 257<br />

Viviparous Blenny 258<br />

Catfish or Wolf Fish 258<br />

Introduction to the remaining species 260<br />

Conger Eel 260<br />

Angler Fish 267<br />

Opah 270<br />

Sunfish 271<br />

Trigger Fish 272<br />

Puffer Fish 275<br />

Lumpsucker 276<br />

John Dory 278<br />

Boar Fish 280<br />

Norway Haddock 281<br />

Bluemouth 282<br />

Greater Weever 283<br />

Lesser Weever 284<br />

Short Spined Sea Scorpion 285<br />

Long Spined Sea Scorpion 286<br />

Blackfish 286<br />

11

Cornish Blackfish 287<br />

Barracudina 288<br />

Butterfish 288<br />

Connemara Sucker 289<br />

Dragonet 290<br />

Great Pipefish 291<br />

Snake pipefish 291<br />

Pogge 292<br />

Red Band Fish 293<br />

Greater Sandeel 293<br />

Corbin’s Sandeel 294<br />

Fifteen Spined Stickleback 295<br />

Argentine 295<br />

Smelt 296<br />

Sand Smelt 297<br />

Big Scaled Sand Smelt 298<br />

Coho Salmon 298<br />

Freshwater fish species<br />

Introduction to freshwater species 299<br />

Carp 300<br />

Grass Carp 305<br />

Crucian Carp 307<br />

Brown Goldfish 308<br />

Roach 309<br />

Rudd 311<br />

Bronze Bream 312<br />

Silver Bream 313<br />

Tench 314<br />

Golden Orfe 315<br />

Barbel 317<br />

Chub 320<br />

Dace 321<br />

12

Bitterling 322<br />

Gudgeon 323<br />

Bleak 324<br />

Perch 324<br />

Ruffe 327<br />

Zander 328<br />

Walleye 331<br />

Pike 331<br />

Silver Eel 335<br />

Wels Catfish 339<br />

Bullhead Catfish 342<br />

Stone Loach 343<br />

Bullhead 343<br />

Minnow 344<br />

Three Spined Stickleback 345<br />

Pumpkinseed 345<br />

Atlantic Salmon 347<br />

Humpback Salmon 349<br />

Brown Trout 350<br />

Sea Trout 354<br />

Rainbow Trout 355<br />

American Brook Trout 360<br />

Grayling 362<br />

Char 364<br />

Schelly, Gwyniad or Powan 369<br />

PART TWO – Fishing abroad and foreign species<br />

Cape Cod 376<br />

Florida - Banana River 379<br />

Florida - Biscayne Canal 381<br />

Florida - Cape Coral 385<br />

Florida – Islamorada 389<br />

13

Florida - Key West 392<br />

Florida – Kissimmee 395<br />

Florida - Port Canaveral 396<br />

Florida - Stick Marsh 397<br />

Rudee Inlet - Virginia Beach 400<br />

Ascension Island 403<br />

Australia 410<br />

Borneo 411<br />

Bulgaria 413<br />

Canada – Fraser River 416<br />

Canary Islands – El Hierro 421<br />

Canary Islands – Fuerteventura 424<br />

Canary Islands – Gran Canaria 425<br />

Cuba 430<br />

Egypt – Lake Nasser 433<br />

Gambia 436<br />

Germany 439<br />

Gibraltar 443<br />

Iceland 446<br />

India 450<br />

Israel 452<br />

Kenya 452<br />

Madeira 454<br />

Malaysia 456<br />

Mallorca 457<br />

Mauritius 458<br />

Mexico 460<br />

Namibia – Skeleton Coast 463<br />

New Zealand 468<br />

Norway 469<br />

Peru – Amazon 472<br />

South Africa 476<br />

14

Spain 479<br />

Thailand 479<br />

Tunisia 484<br />

PART THREE – Individual specimen targets<br />

A national record 485<br />

A European record 493<br />

A world record 493<br />

A Trout in double figures 498<br />

A Bass in double figures 503<br />

A 100 pound fish from freshwater 504<br />

A 200 pound fish from the shore 511<br />

A 200 pound fish from a trailed dinghy 514<br />

A fish in excess of 1000 pounds 520<br />

PART FOUR – Peripheral & historical angling related topics<br />

The evolution of small boat fishing 525<br />

Angling journalism targets and achievements 530<br />

Record and archive 200 audio interviews 533<br />

Fisheries related Ph.D research project 534<br />

A lesson from history 546<br />

Appendix 1: Audio Interview Archive List 552<br />

Photograph Credits & Copy Right 572<br />

15

INTRODUCTION<br />

In theory, there is never an ideal time to present a book such as this built on a finite tick list and<br />

potentially infinite species list. Always there is the chance that something else new will come along,<br />

either on the end of your own line, or added by others to the overall species list. But to write it, there<br />

has to be a cut-off point, and for a number of reasons, late 2015 was mine.<br />

Aged 67, and with every targeted tick in place except for one, that elusive 'grander', I set up a trip to<br />

Ascension with amongst other things, the objective of trying for a thousand pound plus six gilled shark,<br />

knowing that if I got one, the whole project would be complete, and that if I didn't, well, I was getting<br />

too long in the tooth anyway to have another go. So, either way, the timing could not have been more<br />

right.<br />

What I didn't realise when that trip was initially arranged, was that between setting it up and finally<br />

flying out, health-wise, my fishing prospects would take a very rapid down-turn in fortunes, also<br />

pointing to a late 2015 cut-off. By that stage, rapid onset rheumatoid arthritis was making fishing<br />

difficult at best, and at times virtually impossible.<br />

Fortunately, I was able to persuade my consultant to provide me with wrist splints and a steroid injection<br />

for the trip, after which I would have to be more realistic about my day to day activities. Then again,<br />

with the fishing I've enjoyed, the places I've visited, and having virtually no previous medical issues of<br />

note, most people would settle for that. So even if I was forced to completely retire from fishing<br />

tomorrow, which is starting to look increasingly likely, I can't complain.<br />

If you read all four parts of this book in sequence from beginning to end, which I doubt anybody ever<br />

would, it will very quickly become apparent, and I might be criticized for this fact, that there are areas<br />

of over-lap and repetition, particularly between the individual big fish targets and certain home waters<br />

species or venues, and between some of the more closely related home waters species themselves in<br />

terms of identification and tactics.<br />

I make no apology for this fact. The 'Ultimate Angling Bucket List' is not a novel. It's a fact-based<br />

reference book in which every individual unit needs to be able to stand on its own, allowing people to<br />

dip in and out of it at any time and at any point, dependant on what it is they are looking for, and to do<br />

so without the feeling that something is missing which they might need to search for elsewhere.<br />

At the time of writing, there are one hundred and fifty one saltwater species, plus a further thirty six<br />

freshwater fish species officially ratified as caught on rod and line by the combined record fish<br />

committee's of Britain, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, referred to collectively from this point on as 'home<br />

waters' species. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as well as having their own record lists, also<br />

contribute to the overall British record list. But for some inexplicable reason, there is no separate<br />

English record list.<br />

Actually, those species stats are not entirely accurate, as the British Record Fish Committee (BRFC)<br />

appears to have gotten itself into all sorts of difficulties with its record keeping over recent years, with<br />

some species included which for various reasons should not have been, a fact I have pointed out to<br />

BRFC Chairman Mike Heylin, which as an individual I know he is sympathetic to. But as yet the<br />

problem remains unresolved. Where relevant, these will be high-lighted as we go along.<br />

Taking those officially quoted figures then at face value, as I must, we are looking here at a combined<br />

total availability to angling species enthusiasts such as myself of one hundred and eighty seven named<br />

targets, with me wanting to catch at least one hundred of them from home waters, which believe me, is<br />

no easy task.<br />

16

As always, with any sort of ambitious project, things tend to get under-way well enough. Initially in<br />

fact, you race away. Then gradually the brakes start to be applied to the point where, despite at times<br />

making even more of a determined effort than previously, little if any meaningful additional headway<br />

seems to result.<br />

I reckon my brakes started sticking when I got up around the seventy species mark. However, one<br />

anglers stumbling block can be another anglers 'quick tick', for which reason, appreciating that we won't<br />

all be targeting the same one hundred species of fish, I have decided to deal with all one hundred and<br />

eighty seven of them, indicating for each my success or failure, with all sorts of tips, tactics, and relevant<br />

history thrown in for good measure.<br />

Don't however expect the same level of detail for the foreign contingent of my targeted overall total of<br />

three hundred species world-wide. Instead, the foreign fishing will be dealt with on a location by<br />

location basis. Then there's the individual specimen targets, and finally the more peripheral related stuff<br />

such as the journalism and fisheries research.<br />

Things kick off with my main comfort zone, the saltwater species, mainly caught from boats, which for<br />

ease of flow, I'm going to break down under the two natural biological groupings of cartilaginous fishes,<br />

which for our purposes here are the sharks and rays, and bony fishes, which is everything else including<br />

all the freshwater species, dealt with under their various family headings.<br />

A couple of final points to highlight before getting into the main body of the text itself. The first is that<br />

this being a self-published ebook which has not been subjected to the level of proof reading and scrutiny<br />

that a professional printing company might go to, means there could well still be small over-looked<br />

errors here and there which familiarity with the text and electronic spell-checks don't always pick up.<br />

Inevitably, I find a few more each time I read it through. But a point must come when it has to go public<br />

and that time has now passed. So I apologise if any small niggles still remain and trust the book doesn't<br />

suffer too greatly as a result.<br />

The second concerns the presentation of the book completed towards the end of 2016. The final draft<br />

contained just short of 600 illustrations. Unfortunately, ebook publishers are not good at handling file<br />

sizes of that magnitude causing us to think long and hard about the various options open to us, finally<br />

coming out in favour of a three pronged approach. Firstly, whatever we could get out of ebook<br />

publishers such as Smashwords and Kindle; secondly, a fully illustrated version either for reading or<br />

down-loading from www.fishingfilmsandfacts.co.uk, and finally, perhaps half a dozen printed and<br />

bound copies for The Britsh Library, Angling Heritage, and family ownership.<br />

Finally, the Irish listing of roach-rudd and roach-bream hybrids, plus the Welsh listing of ghost, mirror,<br />

and common carp as separate record list inclusions has not been reflected here in the over-all species<br />

count, as hybrids and within species variants are not biologically recognised as separate species of fish.<br />

Sea trout and brown trout, which are also the same species Salmo trutta, should in my opinion also be<br />

treated as a single inclusion too, despite what fish recorders and game anglers might think.<br />

17

PART ONE<br />

HOME WATERS<br />

<strong>THE</strong> CATCHING IN HOME WATERS OF ONE HUNDRED SPECIES OF FISH<br />

FROM <strong>THE</strong> RECORD <strong>LIST</strong>S OF ENGLAND, IRELAND, SCOTLAND AND<br />

WALES.<br />

Bucket List status – result<br />

SALTWATER SPECIES<br />

<strong>THE</strong> CARTILAGINOUS FISHES<br />

These are the sharks and rays. Fish whose musculature is built onto a flexible cartilaginous frame with<br />

only the teeth becoming hardened through calcification. In home waters there are no indigenous<br />

cartilaginous freshwater species.<br />

There are however freshwater rays elsewhere in the world, plus freshwater dwelling bull sharks which<br />

are even more deadly than great whites, exploiting an adaptation that allows them not only to penetrate<br />

rivers and lakes, but also to it seems to breed there.<br />

I haven't caught any freshwater sharks yet myself, but I<br />

have caught freshwater stingrays thousands of miles away<br />

from the sea on some of the Peruvian tributaries of the<br />

upper Amazon.<br />

There are also a few more distantly related cartilaginous<br />

species which are neither sharks nor rays. Deep water<br />

rabbit-fishes for example.<br />

Meanwhile, back within regular angling range, the<br />

monkfish or angel shark as it is now starting to be known,<br />

plus the many sub-tropical and tropical guitar fish species,<br />

are arguably transitional forms between the round bodied<br />

sharks and the flat bodied rays.<br />

For taxonomic classification purposes, monkfish are<br />

included with the sharks and guitar fishes with the rays,<br />

giving a global total of just under a thousand cartilaginous<br />

species, of which almost four hundred are sharks and just<br />

over five hundred are rays, with the remainder being<br />

chimaera's and the like.<br />

Skeletons aside, obvious external features setting<br />

cartilaginous fishes apart from bony fish species include<br />

Amazonian freshwater Stingray having between five and seven gill slits on either side of<br />

the head in the case of the sharks, and on the underside of<br />

the body either side of the mouth in the case of skates and rays.<br />

18

Working in conjunction with these in the skates and rays, on each side of the head close to the eye, is a<br />

small hole known as a spiracle through which water is drawn in to oxygenate the gills over which it is<br />

passed before exiting the respiratory system through the gill slits.<br />

Were skates and rays to take water in through their mouths like bony fish, they would run the risk of<br />

also taking in sand and other unwanted particulate material from the bottom they are resting on.<br />

Spiracles vary in size, though evolution has seen to it<br />

that some of the larger free swimming shark species,<br />

and in particular the mackerel sharks and thresher<br />

sharks, have managed to do away with them altogether,<br />

passing water over their gills via the open mouth<br />

passively while swimming.<br />

Thornback spiracles<br />

One feature however all round bodied cartilaginous<br />

fishes other than angel sharks or monkfishes share is<br />

uneven tail lobes, with the upper lobe always being<br />

longer than the lower, which in conjunction with large<br />

pectoral fins in many open water shark species helps<br />

produce lift when swimming as they are negatively<br />

buoyant and would otherwise sink.<br />

Characteristically, they all also lack traditional scales, having instead opted for small sharp edged overlapping<br />

back pointing denticles for aqua-dynamic stream-lining, which is the reason why they have<br />

such a rough feel when brushed against the grain from tail to head.<br />

Less obvious will be the many tiny pores dotted around the nose and mouth. Dependant on species,<br />

these relay information of varying quality back to one of the most amazing and sensitive natural<br />

detection adaptations known to science, the ampullae of lorenzini. Special jelly filled pores which act<br />

as electro-receptors capable of locating weak electrical impulses from the blood circulatory system of<br />

potential prey items.<br />

This feature is not entirely unique to sharks and rays, all of which have them, as they can also be found<br />

in some non-cartilaginous fishes such as reed fish and sturgeon.<br />

Sharks and rays are also able to pick up subtle pressure<br />

changes using their lateral line. But arguably, the sense<br />

they are perhaps best known for is their legendary ability<br />

to detect minute quantities of blood and other lost body<br />

fluids in seemingly vast volumes of surrounding water.<br />

Smell is the main detection sense acting at long range on<br />

organic traces such as blood, though it is actually tuned in<br />

to a whole range of odours of the type released typically by<br />

injured or distressed prey species.<br />

This is facilitated by the extraordinarily large size of the<br />

Pores – ampullae of lorenzini olfactory lobes of the brain, which when water containing<br />

an odour enters the nostrils, the information provided is<br />

analysed specifically by these lobes, which can be as much as two thirds of the weight of the entire<br />

brain, a level of development unique to sharks and rays.<br />

Having nostrils placed wide apart on either side of the head also allows for directional swimming along<br />

the greatest line of concentration of an odour back to its source, aided by side to side movement of the<br />

head to keep the fish on track. Taste only comes into play once an item of potential interest is located.<br />

19

Test biting then allows taste buds inside the mouth to determine whether the item in question is suitably<br />

edible or not, which explains why surfers and swimmers attacked by sharks are often rejected. The<br />

problem is that because of the high speed mode of attack of say a great white, the damage inflicted can<br />

be so catastrophic that the victim bleeds to death anyway.<br />

Sight is another sense which if the evolutionary processes that have developed it in some shark species<br />

is anything to go by, also plays an important hunting and feeding role. But only at very close quarters<br />

once the other senses have directed the hunt almost to the victim.<br />

Sight generally works on the basis of incoming light being focused by a lens onto the retina at the back<br />

of the eye, which then uses a combination of rods and cones to get the fine detail. The rods detect shades<br />

of light and therefore movement, whereas the cones detect the fine detail and colour, which varies<br />

species to species according to the ratio between rods and cones.<br />

It was thought that sharks and rays could only see in black and<br />

white, and in some cases that may well be the case. But not so<br />

in all species. The human eye, which gives both definition and<br />

colour, has a rods to cones ratio of four to one. Exactly the same<br />

numbers as a great white shark. Other species however have<br />

ratios as low as fifty to one.<br />

Sharks and rays have another visual trick up their sleeve known<br />

as the tapetum lucidum, which is a reflective layer of shiny cells<br />

behind the retina for enhanced low light and nocturnal vision.<br />

Tope eye - nictitating membrane They also have two eye lids, with those species belonging to<br />

the requiem shark family having a third even tougher eye lid<br />

known as a nictitating membrane. This closes upwards from the bottom to protect the eyeball when<br />

attacking prey, something you can see in use when disgorging tope.<br />

Arguably the most important anatomical difference between cartilaginous and bony fishes, certainly<br />

from an angling perspective, is their breeding strategy. Sharks and rays all show clear signs of sexual<br />

dimorphism or outward physical difference based on sex, with long thin modifications to the pelvic fins<br />

known as clasper's in the males which are clearly missing in the females.<br />

These are erectile and are used to transfer sperm into the female during mating, ultimately leading via<br />

one of three different approaches to the production of low numbers of well-developed offspring.<br />

A great survival strategy in some ways in that unlike broadcast spawner's such as cod which eject<br />

potentially millions of eggs and sperm for external mixing, the vast majority of which won't make it<br />

through to adulthood, the offspring survival ratio for sharks and rays can theoretically be very high,<br />

which is great when everything is at a point of natural balance, but potentially disastrous when that isn't<br />

the case.<br />

The first and most primitive of these three approaches, and<br />

the one favoured by rays and dogfishes, is oviparous<br />

reproduction. After fertilization, the eggs are laid in horny<br />

capsules which you often see washed up empty on the strandline<br />

of the beach.<br />

Another approach is viviparous reproduction resulting in the<br />

birth of live fully formed young. Option three, which in terms<br />

of evolutionary progress falls roughly between the other two,<br />

is ovoviviparous reproduction, now also termed aplacental<br />

Viable ray or dogfish egg capsules<br />

20

viviparous reproduction, and the method favoured by most sharks.<br />

Here the fertilised eggs are retained in the two oviducts within<br />

capsules known as candles into which the young will hatch<br />

within the mother. After feeding on the remainder of their<br />

yolk-sac, glands within the mother secrete a nourishing uterine<br />

milk.<br />

Ray about to deposit egg capsule<br />

Later in their development, the most advanced of the pups in<br />

some species become what is termed 'oophagus' and will eat<br />

not only other ovulated eggs, but also their smaller siblings,<br />

which is why ovoviviparous species tend to produce small<br />

numbers of offspring.<br />

A good example of aplacental viviparous reproduction and its potential for unfortunate consequences<br />

is the spurdog. Once this was the most common small shark in northern European waters. I remember<br />

trips back in the 1970's where we would have to up-anchor to get away from the things.<br />

It was like dropping baits into a vast grey hungry swarm, which, because of sexual segregation, which<br />

is common in spurdogs, if the shoal comprised all females, would often see the deck awash with yolk<br />

sac pups.<br />

Not surprisingly, within a very short time the spurdog was a critically engendered species due primarily<br />

to commercial over exploitation, though I'm sure angling must also have contributed here too. A species<br />

fished to the very brink of extinction compounded by the longest gestation period in the animal kingdom<br />

at 22 to 24 months, it has taken many years for even the weakest signs of a comeback to show.<br />

Even when left alone and with optimum offspring survival rates, a few remaining survivors simply<br />

cannot reproduce fast enough to facilitate recovery in the way<br />

that cod and other broadcast spawners with their millions of<br />

eggs per individual potentially can.<br />

It's imperative then that as responsible anglers we do<br />

everything within our power to help not only the spurdog, but<br />

all shark and ray species. Every individual counts.<br />

Unfortunately, proposed EU Common Fishery Policy reforms<br />

offer little in the way of salvation here, and may well<br />

ultimately result in even further problems for already Aborted spurdog pup<br />

struggling species, as it looks likely that all commercially<br />

caught fish in the future will have to be landed in response to the current situation of discards going<br />

back into the water dead.<br />

Some species such as porbeagle sharks and undulate rays may possibly be put onto a prohibited list, for<br />

all the good that will do. The tope was another species up for similar consideration.<br />

Unfortunately, a ministerial meeting in December 2014 decided not to award tope prohibited status due<br />

to objections from France and Spain who collectively have commercially landed over one million tope<br />

in recent times, and who in both cases exercised their veto.<br />

For my money, sharks and rays have poor culinary qualities at the best of times on account of the way<br />

in which they regulate their isotonic balance, as all marine fish must do due to the salinity of their<br />

environment being greater than that of their body salt concentration.<br />

The reason why the cartilaginous approach to isotonic balance makes for poor eating is because it can<br />

make the flesh both taste and smell like an incontinence pad.<br />

21

Marine bony fishes have to drink sea water to make up for losses from their cells, as the salinity either<br />

side of their cell membranes strives to find a balance through the process of osmosis drawing water out<br />

from their body. The salt in the water they drink is removed by the fish and excreted through cells in its<br />

gills.<br />

The reverse is true in freshwater species where the water surrounding them is less salty than in their<br />

cells, so water is absorbed, again in an attempt to achieve isotonic balance, which they can never do, so<br />

their kidneys must constantly off-load the excesses as urine.<br />

Cartilaginous fishes on the other hand are osmo-conformers. They achieve this by maintaining high<br />

urea levels within their tissues and body fluids. As the salinity of this can be at a slighter higher level<br />

than the surrounding sea water, a small amount of water is taken in via the gills which is later excreted<br />

along with excess urea. This explains the smell (and sometimes the taste) of ammonia in these fish.<br />

Unfortunately sharks and rays can only manage to achieve this at quite an advanced developmental<br />

stage, which in the case of egg laying rays and dogfishes prevents their eggs being deposited outside of<br />

the body without an impervious protective case containing fluid of a lower salt concentration than the<br />

environment outside.<br />

To avoid repetition, now might be a good time to comment on the handling of sharks generally, both<br />

for their well-being and that of anglers fingers and hands. Fearsome apex predators they may well be,<br />

but they are also highly sensitive animals, which even though they might appear to swim away<br />

unharmed, can die a slow lingering death later as a result of in-appropriate treatment.<br />

The first point to be made is to opt for in-water release if there is no pressing need to have a fish inside<br />

the boat. If it must come aboard, either for disgorging, weighing, or even a photograph, then wherever<br />

Tope supported in a weighing sling<br />

22

possible, use a landing net, and that goes for tope too which some charter boat skippers now routinely<br />

do.<br />

If you don't have a net and intend lifting a fish in, always try to keep it horizontal using the tail and<br />

either a pectoral fin or the dorsal fin as gripping points, then lay it down slowly and carefully onto the<br />

deck, all of which I know is easier said than done. But at least be prepared to try.<br />

The reason for this is simple. In-appropriate handling, particularly tail lifting either into the boat or for<br />

a photograph can lead to unseen internal bleeding and possibly even death.<br />

What happens is that when a big fish is removed from the support given to it by the surrounding water<br />

pressure, if not given replacement support either by the mesh of a landing net, the deck of the boat, or<br />

being cradled in an anglers arms, which I appreciate is not always practicable, then the heavy organs<br />

inside the body cavity can shift through gravity rupturing internal blood vessels.<br />

So get the fish down on the deck as soon as possible, cover its eyes with a wet rag to quieten it down,<br />

and if necessary, leave a deep seated hook in place rather that struggling to free it. Unless made of<br />

stainless steel, it should rot away over time. And always weigh sharks of all sizes and species using a<br />

supportive weighing sling.<br />

Female Ray – no claspers<br />

Male Ray – long claspers<br />

As for the skates and rays, these are just dorso-ventrally flattened out sharks. In other words, they've<br />

settled out on the sea bed resting on their stomachs, with their mouth, gills slits and anus underneath,<br />

unlike conventional flatfish species such as plaice and dabs which have come to rest on one side of their<br />

body, prompting the eye from the underside to migrate around the head to join its partner on the top.<br />

Another way of putting it is that rays are little more than smoothhounds or dogfishes that have been put<br />

through a mangle. Also with skates and rays, the pectoral fins have become enlarged and fused to the<br />

front of the head while extending horizontally outwards to form their now familiar wings.<br />

The obvious question here is what is the difference between the skates and rays. Anglers tend to see the<br />

smaller species with a short rounded snout and nipple like tip as being rays, while the larger species in<br />

which the wing tip takes an almost continuous line through to the end of a long well angled pointed<br />

snout are the skates.<br />

In actual fact, these are interchangeable terms, both of which have equal meaning and validity, which<br />

is perhaps as well with the white skate or bottle nosed ray as it is also known, having a foot in both<br />

those camps, with its well defined long nipple like snout, and a capacity to grow to something like two<br />

hundred pounds.<br />

The stingrays, eagle rays and electric rays, all of which are recorded from home waters, are the only<br />

true rays here. However, within the smaller skate-ray species there is one other very obvious and helpful<br />

23

identification feature worth noting. The thornback, small eyed, spotted, and blonde rays all have pointed<br />

wing tips, whereas the undulate, sandy, and cuckoo ray have noticeably rounded wing tips.<br />

SHORTFIN MAKO SHARK Isurus oxyrinchus<br />

Bucket List status – no result yet<br />

Andy Griffith’s fabulous Welsh Mako Shark<br />

Reputedly the fastest swimming shark in the sea with bursts clocked in excess of thirty knots. Also a<br />

species prone to leaping from the water when hooked, the mako is a beautifully streamlined yet heavily<br />

built fish with a sharply pointed snout.<br />

The first dorsal fin originates behind the origin of the pectoral fins, and the tiny second dorsal slightly<br />

ahead of the anal fin beneath it, whereas in the similar looking porbeagle shark, the dorsals originate<br />

over the origins of the pectorals and anal fin.<br />

The mako also has a single keel on the side of the tail stalk just in front of the tail lobes, while the<br />

porbeagle has both this and a smaller secondary keel below it.<br />

Colouration is a dark petrol blue giving way suddenly to pure white on the lower flanks and underparts.<br />

A fish that is still at times confused with the porbeagle shark for which it has a passing<br />

resemblance.<br />

24

Only when a world record claim was was made for a 352 pound porbeagle by Hetty Eathorne caught<br />

off Looe in 1955 and subsequently rejected by the IGFA because it turned out to be a mako shark, did<br />

the angling presence of the species as far north as the British Isles first come to light.<br />

Though there are external anatomical differences if you<br />

look carefully enough for them, the IGFA identification<br />

was made solely on the basis of the teeth. Those of the<br />

mako are long and pointed without cusps at their base,<br />

whereas porbeagle teeth are more triangular with very<br />

obvious cusps or spikes at either side.<br />

Unlike porbeagle's, mako's are northerly migrants from<br />

warmer southern seas to the Biscay area and extreme<br />

south-western parts of the British Isles, though there is<br />

no predictable pattern to any of this.<br />

An open water species usually found well offshore,<br />

often very close to or actually at the surface. Lengths of<br />

up to twelve feet have been recorded with weights well<br />

in excess of a thousand pounds, though half that size<br />

would be nearer the European maximum.<br />

Every mako shark I am aware of on rod and line in home<br />

waters has either come from, or very close to, the<br />

western approaches to the English Channel, and that<br />

includes specimens over on the Irish side.<br />

Some serious Mako dentistry To be even more specific, from the time that first 1955<br />

mako was correctly identified through to a fish caught<br />

by David Turner in 1971, I believe that every single UK specimen was taken by boats working either<br />

out of Looe around the Eddystone, or Falmouth around the Manacles and just beyond.<br />

In total, according to research figures provided by David Turner, forty five mako sharks were caught<br />

on rod and line during that period, of which thirty, which is two out of every three, fell to the Falmouth<br />

boats, and one skipper in particular, that being Robin Vinnicombe aboard his boat Huntress'.<br />

In addition to meeting up with and recording an audio interview with Robin Vinnicombe on the subject,<br />

I have similarly spoken on the record with Robin's brother Frank, and with David Turner, resulting in<br />

conflicting accounts of who actually caught what, though the weight of evidence from a variety of<br />

sources seems to sit most comfortably with Robin Vinnicombe and David Turners version of events.<br />

In fact, it was on Robin's boat that David Turner took his fish, which at the time of recording the three<br />

interviews was the last mako shark taken on rod and line in British waters, a fact that has always struck<br />

me as being odd, as mako sharks are supposedly a warm water species.<br />

You might be forgiven for thinking that if global warming and rising sea temperatures are a reality, we<br />

should have seen a steady stream of mako sharks since 1971, which catch statistics clearly demonstrate<br />

obviously isn't the case.<br />

In my personal opinion, a number of factors are operating here. First off, at the best of times, mako<br />

shark visits at our latitude have never been a common occurrence. Even when the popularity of shark<br />

fishing was at its height, which coincided with pretty much all of the recorded mako catches, they were<br />

still very rare fish indeed.<br />

25

Later, when interest in blue shark fishing slipped into decline resulting not only in far fewer baits in the<br />

water, but equally, fewer rubby dubby trails up which to entice an occasional visiting mako, a numerical<br />

drop off in the catch rate of an already rare and accidental encounter was always likely to be the result.<br />

The same numbers of visiting fish may well have continued coming. But with fewer anglers out there<br />

in with a shout of hooking one, the chance encounter rate understandably went right down the pan. That<br />

is until recently when South Wales skipper Andrew Alsop revived UK shark fishing big style aboard<br />

his boat 'White Water' out of Milford Haven.<br />

Catch rates and sizes for both blue sharks and porbeagle's aboard 'White Water', along with boats<br />

operated by Rob Rennie and Craig Deans have been outstanding, and as such, getting a spot on-board<br />

any of these three boats is understandably at a premium.<br />

One man who has spent a lot of time with Andrew Alsop is Kent property developer Andy Griffith who<br />

charters 'White Water' all to himself to have the very best shot, albeit an expensive shot, at anything<br />

good that might come along.<br />

As expected, though long overdue, in 2013 the two Andrews combined to catch and release the first<br />

UK mako shark in thirty seven years, on a day which amongst other things also turned up both blue and<br />

porbeagle sharks in excess of one hundred pounds, making it the first ever ton up grand slam of the<br />

three shark species in question ratified by the IGFA.<br />

How long it will be before we see the next mako is open to debate. Shark fishing in that corner of South<br />

Wales is still developing. As ever, the more rubby dubby lanes and shark baits there are going out into<br />

potential mako shark territory, the greater the chances of a repeat. But the odds were never high, not<br />

even when they were at their peak.<br />

Associated audio interview numbers: 31, 109, 112 and 137<br />

NOTE: As most mako sharks have been caught while fishing for blue sharks, from a tactical point of<br />

view, it might help to also read the blue shark account, particularly the part about rubby dubby and bait<br />

positioning.<br />

PORBEAGLE SHARK Lamna nasus<br />

Bucket List status – result<br />

A more stocky, heavily built fish than the<br />

mako, which if I'm honest, is a statement<br />

only of any real value when a straight<br />

comparison between these two related and<br />

similar looking species can be made.<br />

So superficially similar are they in fact that<br />

a claim submitted to the IGFA for a 352<br />

pound porbeagle caught by Hetty Eathorne<br />

in 1955 ultimately turned out to be Britain's<br />

first authenticated rod caught mako shark.<br />

That's a measure of how similar they are.<br />

Andy Griffith, Porbeagle<br />

Unlike the mako, whose first dorsal fin<br />

originates behind the origin of the pectoral<br />

fin, the origin of the first dorsal fin of a<br />

porbeagle is directly above the origin of the<br />

26

pectorals, with the second dorsal directly above the anal fin.<br />

Like the mako, there is a keel on the side of the tail-stalk just in front of the tail. But unlike the mako,<br />

there is also a smaller secondary keel just beneath it running onto the tail. However, it was the teeth that<br />

solved the riddle for the IGFA. Porbeagle teeth are more triangular than mako teeth, with obvious cusps<br />

or spikes at their base. Colouration is very deep blue to dark grey with off white lower regions.<br />

In angling terms, this is very different fish to the mako shark. For starters, it's more abundant, more<br />

widespread well up into northern latitudes so obviously better cold water adapted, and more willing to<br />

feed incredibly close to the shore. So close in fact that over in Ireland specimens have actually been<br />

caught from the shore, though not unfortunately in recent years.<br />

During the 1960's and 70's, the eastern fringe of the Isle of Wight and the inshore waters along the North<br />

Cornish Coast through on into North Devon were the UK's main porbeagle grounds, with Padstow being<br />

the Mecca to which most big shark enthusiasts at that time would gravitate. Then in seemingly no time<br />

at all, things started to change and catch rates went into decline.<br />

Angler pressure certainly won't have helped. Most sharks were killed and brought ashore back then,<br />

even the blue's. But if the truth be known, commercial pressure contributed most to sending porbeagle<br />

populations into free fall, which a slow growing and equally slowly reproducing species such as this<br />

was never going to be able to withstand.<br />

That said, all was not lost. Other holding areas were discovered around the country, and for a short<br />

while at least, it remained business as usual, albeit in some cases with smaller fish in fewer numbers as<br />

Wales and Scotland started to come into the frame.<br />

Porbeagle pioneers such as Mike Thrussell helped Aberystwyth and Aberdovey mid-way down<br />

Cardigan Bay in West Wales build themselves quite a reputation back in the 1980's, though as with the<br />

trend of their contemporaries, that too didn't last long either.<br />

Most of the fish there were at the smaller end of the size range, coming in just either side of the one<br />

hundred pound mark, which was way short of the average for the Cornish fish. And again unlike the<br />

Cornish fish, they were also found much further offshore.<br />

Then they too were gone, supposedly fished out commercially around Lundy Island which formed a<br />

part of their predictable migration ritual, though yet again, with seemingly all specimens brought ashore,<br />

angler pressure can't have helped.<br />

As for the Scottish link, that had been<br />

demonstrated as far back as the early 1970's<br />

when a friend of mine, the late Dr. Dietrich<br />

Burkel, set out on a summer long quest to<br />

demonstrate that porbeagles could be<br />

caught that far north, eventually taking one<br />

from a dinghy fishing off the tip of the Mull<br />

of Galloway. A catch that would later have<br />

quite a bit of controversy attached to it,<br />

much of which was sour grapes, which<br />

Dietrich cleared up in a recorded interview<br />

we did in 2013 just a few weeks before his<br />

death.<br />

Graeme Pullen, small dinghy Porbeagle<br />

A couple of other small specimens were<br />

also taken over the years in and around<br />

Luce Bay. But Scottish shark fishing never really came to muh until good numbers of big porbeagles,<br />

27

world all tackle records included, were discovered off Sumburgh Head in Shetland and Dunnet Head<br />

on the Pentland Firth.<br />

The west coast of Ireland, in particular Co. Clare was also a regular producer, including those shore<br />

caught specimens mentioned earlier by legendary Irish angler Jack Shine fishing from Green Island at<br />

the mouth of Liscannor Bay. But sadly, there too the trail now seems to have gone cold.<br />

However, in West Wales in July 2016 fishing from a well known rock mark, Simon Shaw and Mark<br />

Turner beat and released the UK's first ever shore caught porbeagle which had taken one of their tope<br />

baits, the fish being estimated at around 150 pounds.<br />

Though perhaps not immediately obvious, there is a link here between many of these potential porbeagle<br />

holding areas, with the possible exception of Cardigan Bay. That link is disturbed tide of the kind often<br />

produced by islands and headlands with submerged reefs and strong local tidal influences, though it<br />

should also be said that many of the current Milford Haven fish are taken well offshore.<br />

The Isle of Wight, Mull of Galloway, Lundy Island, Sumburgh Head and Dunnet Head are all typical<br />

examples. And let's not forget the stretch of coastline to the north of Padstow running across the Devon<br />

border up to Hartland Point, because this is where my link to the scene kicks in. An episode which starts<br />

with Graeme Pullen, Pete Scott, and a small trailed fifteen foot displacement boat launched (and<br />

occasionally swamped) through the pounding surf tables at Bude in the late 1990's.<br />

Graeme's exploits with big sharks on the world stage are legendary, so if there were sharks there for the<br />

taking, he was the man who would find them. But even he was to be surprised by the levels of their<br />

success. For while it had long been the known that porbeagles in the area frequented the tide rips and<br />

headlands dotted all along this inhospitable stretch of cliffs, most people had given up on trying for<br />

them thinking they had all gone. But not so, as Graeme and Pete would demonstrate.<br />

Some of the encounters the duo experienced close into shore were scary on a number of fronts. Huge<br />

fish in poor conditions from such a small boat, broken rods, big sea's, and with absolutely nowhere to<br />

run to in a sudden bad weather emergency, this can be a most unforgiving area, but also a very<br />

productive one, both for big fish and for big numbers of fish.<br />

Fortunately, they survived it, though at<br />

times perhaps only just, coming away with<br />

the knowledge that the very biggest fish<br />

were still there to be found almost within<br />

touching distance of the shore during March<br />

and April, backed up by larger numbers of<br />

smaller pack fish in the sixty to eighty<br />

pound bracket further off over the summer<br />

months.<br />

Porbeagle at the boat<br />

any stretch of the imagination.<br />

Typical of a summer trip is a two day<br />

session Graeme and I videoed for YouTube<br />

in 2009 aboard his seventeen foot Wilson<br />

Flier. By this stage, Boscastle had taken<br />

over from Bude as a far safer launching<br />

site, though not without its own pitfalls by<br />

The harbour there sits in a long very narrow ravine with poor access and a ramshackle slipway which<br />

can only be used for maybe half an hour or so either side of high-water on a big tide. Then there's the<br />

exit-entrance which is an 'S' shape.<br />

28

The harbour itself completely dries at low tide, and the opening is difficult to find on the way back in<br />

as it blends into the surrounding cliffs, in addition to which, when you go out, regardless of what the<br />

open Atlantic might throw at you, that's it for at least ten hours with nowhere else to sun for safety.<br />

Other than that, Boscastle is ideal, and a vast improvement on Bude, though on this occasion, it being<br />

midsummer, the radar dishes to the west of Bude were to be our destination anyway, drifting maybe a<br />

mile of so off the coast in around eighty feet of water.<br />

Key to good porbeagle fishing is rubby dubby. The more you put in, the more potentially you get back<br />

out in return. This cannot be over stressed, despite making repeated fairly short drifts which breaks the<br />

trail and could it's argued confuse the fish.<br />

Not just any rubby dubby either. Graeme is friendly with the people who run Avington trout fishery in<br />

Hampshire where they save the filleted carcases and fatalities for him. He then mashes them up, adds<br />

bran, and freezes it in onion bags ready to go at the drop of a hat.<br />

You could of course use mackerel if you can catch them, which probably won't be possible in March or<br />

April. But as oily as they are, mackerel don't come anywhere close to pellet fed trout, which literally<br />

ooze oil into the water.<br />

So there we were with four rubby dubby bags out fishing whole mackerel baits on 10/0 O' shaughnessy<br />

hooks to five feet of four hundred pounds wire attached to a further eight feet of similar strength mono,<br />

suspended under lightly inflated balloons set at various levels around three quarters of the depth of the<br />

water column using fifty pound class outfits.<br />

Not over inflating the balloons can be<br />

very important, as despite being apex<br />

predators, porbeagles can at times be<br />

quite skittish fish and will not take a bait<br />

they have any suspicion about,<br />

particularly if the balloon creates too<br />

much drag due to its size.<br />

Even so, some of the takes were still<br />

fickle. Tugs and snatches, or simply float<br />

bobbing with short half-hearted runs.<br />

Very much a waiting game, often not<br />

knowing when or if to strike, which<br />

unfortunately can lead to swallowed baits<br />

and deep hooking which is the last thing<br />

any of us want.<br />

Jack Shine, shore caught Porbeagle<br />

Maybe the answer would to use circle<br />

hooks which only expose the point in the direction of flesh as they exit the mouth where they invariably<br />

make contact in the scissor.<br />

Even for fast hard running fish such as blue sharks and tope they might prove useful, though for different<br />

reasons. Not so for skates and rays though. There are other ways to prevent more sedentary species<br />

becoming hook damaged.<br />

I think it's worth saying a few words about floats generally at this point, as some of the methods of<br />

suspending baits in the water can create more problems than they cure.<br />

29

In the early days, floats were circular net corks with a hole in the centre which were threaded on to the<br />

reel line. They would then have a knife cut in the side of the hole for the line to be pulled into and<br />

trapped which could quickly be released once the cork came back within reach.<br />

Plastic bottles, lumps of polystyrene; I've seen them all. But without doubt the best approach is to lightly<br />

inflate a balloon tying the end obviously so it stays up, then wrap an elastic band around the reel line a<br />

few times at the required depth, inserting the knot in the balloon through the two free end loops which<br />

will clamp up locating it in place. Then, when the balloon comes back within reach, simply pull it clear<br />

snapping the elastic band, leaving the line to run back freely through the rod rings or rollers.<br />

We knew we were after relatively small fish, which for the most part is what we got. But we were also<br />

rewarded with a lively specimen to my rod of around a hundred and seventy pounds, which proved<br />

much more of a handful.<br />

At one point, with the angle in the line rising towards the surface at long range, I thought it was going<br />

to jump, and secretly had my fingers crossed that I might be on for a mako. Then it went down again<br />

and gave me quite a mauling before we had it to the boat, disgorged, tagged and away.<br />

Surprisingly, we also had tope come right up off the bottom to take the shark baits, and conversely,<br />

when we put baits down on the bottom aimed at targeting tope, some of those were picked up by<br />

porbeagles too. But in the main, the tactics described offer the best option.<br />

I have tried to get down to Boscastle in the<br />

spring for a crack at the biggies, but invariably<br />

the weather has stepped in and written off all<br />

my attempts. Well, I say all of them, but<br />

actually that should read all but one which I<br />

couldn't make because of other commitments,<br />

leaving Wayne Comben to step in and take my<br />

place.<br />

A cold grim couple of days in reasonable<br />

conditions spent doing all the usual stuff, but<br />

very much closer to the shore making short<br />

drifts through known holding spots off the<br />

Porbeagle teeth<br />

headlands where the big female fish come in<br />

to pup. Quite a slow couple of days too as it<br />

turned out, until one obviously very good fish started going nuts at the surface in the slick.<br />

To cut a long hard fought story short, that fish, played by Wayne and filmed by Graeme, appeared all<br />

over the TV news and press with an estimated weight way in excess of the current all tackle World<br />

record of 504 pounds. Not that record proportions matter on a number of fronts here. After-all, what<br />

can you do with a shark of that size in a seventeen foot boat even if you had wanted to weigh it, besides<br />

which, how can anybody kill such a magnificent fish anyway.<br />

Into the bargain, and in common with a number of threatened cartilaginous species, the Convention on<br />

International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) now lists the porbeagle shark as being in need of<br />

protection, in addition to which, all commercial and recreationally caught porbeagle sharks must now<br />

be returned at the point of capture right across all EU member states.<br />

Quite where this leaves the British Record Fish Committee is anybody’s guess. But they need to deal<br />

with this situation and quickly, as anglers can no longer comply with their insistence that all record fish<br />

must be weighed on firm ground and not in a boat.<br />

30

Nor can weights be estimated by using length and girth measurements, all of which rather makes a<br />

mockery of record keeping as it currently stands. Some sort of weight estimation formula needs to be<br />

agreed and urgently.<br />

Associated audio interview numbers: 52, 54, 90, 120 and 141.<br />

NOTE: Milford Haven in Wales is currently the UK's chartering 'in venue' for all things shark fishing<br />

with Andrew Alsop aboard his boat 'White Water', Rob Rennie on 'Lady Jue 3', and Craig Deans aboard<br />

'Phatcat'.<br />

THRESHER SHARK Alopias vulpinus<br />

Bucket List status – no result yet<br />

Rob Rennie & Andy Turrell, Welsh Thresher<br />

A temperate water family of sharks containing four species world-wide, all characterised by the length<br />

of their tail, which can be almost equal to the length of the rest of the body. As only one species is<br />

recorded from northern European waters, identification should present no problem whatsoever.<br />

Colouration varies from bluish grey through to brown and is white ventrally. Though recorded<br />

throughout all northern European waters right up to the Arctic, numbers actually penetrating north of<br />

the English Channel are not thought to be high, with both commercial and angling catches suggesting<br />

this is not an abundant fish anywhere, though specimens both turn up and are spotted with reasonable<br />

regularity.<br />

31

As with most pelagic sharks, actual sea bed geography probably means very little here. A fish found<br />

living and feeding in the mid to upper layers often quite close to the surface, and often in fairly shallow<br />

water, with a taste for various small fish, in particular pelagic shoaling species such as mackerel, herring<br />

and pilchard.<br />

The long tail is used to great effect when prey fish are encountered. The thresher will circle a shoal,<br />

balling it up by thrashing its tail which may also stun some individuals which are picked off after the<br />

initial attack.<br />

Something of a prestige species on account of its rarity in northern European waters, the thresher shark<br />

is caught in much the same way as the other recorded shark species, using similar gear, tactics, and<br />

rubby dubby to that outlined already for porbeagle fishing.<br />

Most recorded specimens in fact have been taken by anglers targeting porbeagle's, though legendary<br />

skipper Ted Legge fishing out to the east of the Isle of Wight made quite a name for himself in much<br />

the same way that mako skipper Robin Vinnicombe did, by taking many more than his fair share over<br />

the years.<br />

Obviously then he was doing something right. Again, location it seems has a big part to play, and for<br />

some reason, the area to the east of the Isle of Wight both was, and probably still is, for whatever reason,<br />

particularly attractive to visiting threshers. But there has to be more to it than that.<br />

Of course, there needs to be fish there to target. But it's how you target them it seems that also counts,<br />

and in that regard, Ted Legge most certainly had it well and truly sussed.<br />

As mentioned earlier, baits – in this case a small single mackerel due to the threshers relatively small<br />

mouth, suspended under floats at increasing depths with distance from the boat in a good rubby dubby<br />

slick, which itself becomes deeper further away from the boat as the heavier particles start to sink.<br />

This is the time honoured shark fishing approach, and no doubt some of the threshers, as well as<br />

porbeagle's would have been taken in this way. But most definitely not all of them. For invariably Ted<br />

Legge would also drop a bait straight down to around mid-water and leave it to hang there with the<br />

ratchet set on the reel, and it was this that would account for many of his customers fish.<br />

Thresher sharks pretty much went off the reporting radar for quite a few years after the porbeagle<br />

population collapsed around the Isle of Wight. Again, the link there I guess being lack of baits in the<br />

water leading to fewer if any bonus thresher shark hook ups.<br />

The same is probably true for other shark fishing areas around the country, though despite reported<br />

sightings and the odd accidental commercial encounter, plus plenty of shark angling activity, the West<br />

Country ports both north and south of the Lizard have added very few inclusions to the UK thresher list<br />

over the years.<br />

That said, buoyed up by his successes with the big Boscastle porbeagle shark already detailed, plus<br />

some amazing dinghy blue shark fishing out from Falmouth with Graeme Pullen, Wayne Comben, who<br />

fishes out of Langstone over-looking historically the best thresher shark grounds in the country, decided<br />

to launch an all-out attempt from his own Wilson Flier in 2013.<br />

Initially fishing alone, and with several blanks already to his credit, he eventually teamed up with<br />

Graeme, who while perhaps not expecting to see much in the way of action, tagged along with the video<br />

camera to make a historical documentary on the attempt, little knowing that it would make angling<br />

history in its own right.<br />

This was done with a huge thresher shark easily twice the size of Steve Mills British record taken back<br />

in 1982, also from a dinghy fishing the same area off the Nab Tower, and again, as with the duo's blue<br />

32

shark and porbeagle exploits, all on YouTube as part of Graeme's Totally Awesome Fishing Show<br />

collection.<br />

At one point at the side of the boat, the huge fish whipped its tail right across the two gunnel's, narrowly<br />

missing both Graeme and Wayne in the process. But eventually it was measured, tagged, disgorged,<br />

and sent on its way.<br />

In July 2015, the species put in a surprise double showing off the coast of South Wales. For years the<br />

Welsh record slot had stood vacant, then to use the old bus stop cliché, you wait for ages then two come<br />

along at the same time (well, almost).<br />

The first at 253 pounds was taken by Andy Turrell aboard Rob Rennie's 'Lady Jue 3' off Milford Haven,<br />

with the second three days later by Dave Thomas aboard 'Phatcat' skippered by Craig Deans also fishing<br />

the same area. So as with Andy Griffith's Mako Shark, again from Milford Haven aboard Andrew<br />

Alsops 'white Water II', if you put in the sea hours and play the percentages game, good things should<br />

eventually come your way.<br />

And one year on the British thresher record was bettered with a fish given a weight of 368 pounds<br />

caught and released by Nick Lane out from Illfracombe, the weight having been estimated from<br />

measurements given to the Shark Trust. Note: catch and release means that no official record claim can<br />

be made.<br />

Associated audio interview numbers: 141.<br />

NOTE: As most thresher sharks have been caught while fishing for porbeagle sharks, from a tactical<br />

point of view, it might help to read the porbeagle account, particularly the part about tackle and tactics.<br />

BLUE SHARK Prionace glauca<br />

Bucket List status – result<br />

Blue sharks are open oceanic fish found in all warm<br />

temperate, sub-tropical, and tropical seas world-wide where<br />

the depth exceeds around forty fathoms. In northern<br />

European waters they are most regularly found throughout<br />

the Biscay area, the western English Channel, and off the<br />

south and west coasts of Ireland.<br />

Occasional isolated specimens have turned up in western<br />

Scottish waters, and even further to the east off southern<br />

Norway, but such occurrences are rare. Long warm<br />

summers and prolonged south westerly winds will increase<br />

arrival numbers, and can extend their range to higher<br />

latitudes.<br />

Blue shark are pelagic hunters of small shoaling species<br />

such as mackerel, pilchard, and herring which frequent the<br />

upper layers of the water column. Squids too as they hunt<br />

close to the surface late in the day may also be taken.<br />

Mike Pullen, Irish Blue Shark<br />

In terms of physical appearance, a noticeably long slender<br />

fish with a long pointed snout and long curved sickle<br />

shaped pectoral fins. A strikingly beautiful animal, its<br />

33

upper surface being a deep inky blue giving way to a more brilliant shade of blue lower down the flanks,<br />

and an unbelievably pure white on its under-parts.<br />

Blue sharks have always visited the warmer parts of Europe, either where general sea temperatures have<br />

not been restrictive, or where warm water arms of the North Atlantic Drift or Gulf Stream have allowed<br />

them to penetrate beyond their normal latitude.<br />

For many years they were accidentally caught by Cornish pilchard netters who saw them as little more<br />

than a pest, though during the 1950's they would also become a much appreciated extra source of<br />

income, particularly later on as the pilchard fishery went into decline and a few early pioneering shark<br />

anglers began to sit up and take notice.<br />

This eventually led to the group embarking on a quest that would ultimately result in the tried and tested<br />

blue shark fishing techniques still used today, and to the port of Looe, which up until the 1980's at least,<br />

took pride of place on the UK shark fishing map.<br />

Shark fishing in northern European waters, and off Britain and Ireland in particular, differs radically in<br />