This exhibition of a supposedly “great” Canadian artist who was unsuccessful in his own lifetime and is little-known outside his own country today is called David Milne: Modern Painting. I don’t know what definition of modern painting they used, but it isn’t in any of my books. Milne’s paintings are only modern if by that you mean a wishy-washy vagueness, depressed colours and complete lack of shock. This is the cough of the new, modern art with a yawn.

There is very little sign of development in Milne’s art, and as you navigate his backwoods the monotony of his subdued palette of russets, pale greens, blacks and muddy browns becomes embarrassingly repetitive.

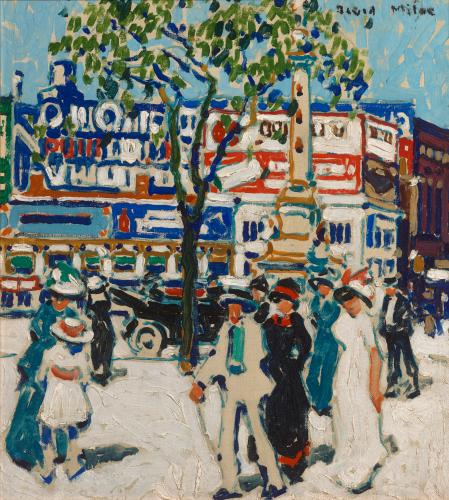

Milne, born in Ontario in 1882, started his career in gilded age New York – already the art capital of the Americas by the 1900s. He painted softly toned scenes of city life that make Manhattan look like a corner of Edwardian Bloomsbury. His dappled studies of women in big hats, people milling about in the Public Library, a couple of cars and some sedate hoardings are timid imitations of the likes of Matisse and Bonnard. Compared with the paintings of George Bellows or photographs of Alfred Stieglitz from the same era, with their powerful sense of a great urban society, Milne’s perceptions of New York are tediously genteel.

He obviously did not feel at home in the metropolis and in 1916 – suffering from what he described as a “nervous heart” – moved to the first of a series of hideaways in the mountains of New York State, before eventually returning to Canada in 1929. From 1916 onwards, the exhibition is dominated by woodland landscapes. In his 1916 watercolour Bishop’s Pond (Reflections), he finds a mirror of his melancholy in the glassy surface of a woodland pool. White, snowy trees become blurred forms of reflected sadness. Yet the exhibition’s attempt to compare his love of reflections with Monet’s waterlilies reveals a loss of perspective. One of Milne’s landscapes might be touching; together, they pall. He seems unable to take his imagination outside a very limited repertoire. In 1929, for instance, he is still brooding miserably on woodland water in the appropriately titled Gray Pool.

When Milne visited the western front in 1919 as an official Canadian artist, the first world war was over and its eerie potholes and trenches gave him plenty of mud and rainwater to brood on. He himself said he was merely a “tourist” among these haunted landscapes. His war art is not especially powerful. Milne was a misery before he visited the trenches and a misery afterwards. Obviously any image of those landscapes of horror is distressing. Yet it is hard to see what Milne’s dappled renditions add to the photographs of the same scenes that are displayed for comparison. The photographs are brutally real, the paintings almost decorative.

That same contrast between the raw reality of the camera and the gentle artifice of Milne’s brush recurs when the woodland photographs he took as part of his research are shown beside his pastoral scenes. I prefer the photos. I have never thought that about a painter before.

This venerable gallery – with its wonderful architecture by John Soane and collection of masterpieces by the likes of Rembrandt and Poussin – is a beautiful place, yet its exhibition programme is turning into an orgy of the second rate. It’s time Dulwich celebrated what it is, an art-historical treasure house, instead of trying to be “modern” and getting lost in some very dreary woods.

- David Milne: Modern Painting is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, from 14 February to 7 May.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion