“He makes a mockery of the old fashioned frozen-stone school of sculpture,” wrote the New Yorker critic in 1929, referring to the 31-year-old American sculptor Alexander Calder, maker of quicksilver wire figures that could be packed away in a suitcase, and soon to be the maker of wafer-thin mobiles that could be moved by a child’s breath. Calder’s equivalent of the bashful Medici Venus were his wirework portraits of the exuberant African American dancer Josephine Baker, her convulsive jazz-age moves and rolling eyeballs traced in wire that is wobbly yet attenuated, and seemingly sketched out in a second – a single strand per limb, a spiral for breasts, a squiggle for hair.

Although Calder, who died in 1976, was clearly no neoclassicist, his informal approach to sculpture did not come out of thin art-historical air. Ever since the Renaissance, sculptors have used wire armatures, frameworks to support clay or wax models for sketching – this is precisely how Degas made his wax statuettes of stretching dancers and bathers. In the 1920s Picasso, with the help of Julio González, made open-frame wire sculptures that were dubbed “drawings in space”. Calder’s wire works could be called the armature unleashed.

Calder would have learned about armatures from his father, the successful public sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder. Calder Sr tends to be written out of his more famous son’s story, and commentators simply say that Calder Jr trained to be a mechanical engineer – as if an engineering degree were a necessary prerequisite for making mobiles that are, technologically speaking, Heath Robinson. But Calder Sr is not only crucial for introducing his son to armatures, he also exposed him to improbable, anti-gravitational sculpture. In 1915, Calder Sr made the first of several fountains, The Fountain of Energy, for the San Francisco World Fair. A man on a horse, with trumpet-blowing angels standing on his shoulders, was placed on top of a huge terrestrial globe that spurted jets of water. Calder Jr shared in this utopian sensibility that would so mark the interwar years. His wirework depicting a human pyramid of acrobats, The Brass Family (1929), is clearly inspired by his father’s fountains; and the kinetic trajectories of some of his mobiles of the 1930s and 40s recall the interlaced water jets. Yet he always laced his father’s messianic fervour with dry, bathetic humour.

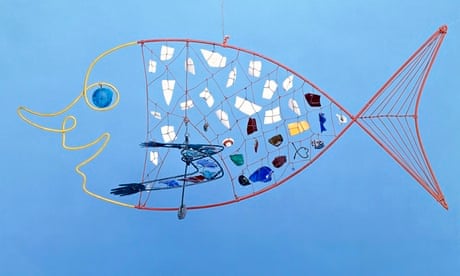

Calder studied drawing and painting in New York, and became a commercial sketch artist: his first book, Animal Sketching (1926), was illustrated with studies of animals in motion, drawn at the city’s two zoos. In 1926 Calder moved to Paris, the centre of the contemporary art world, to attend drawing classes, and it was here that he developed his distinctive language of abstract form. He soon became friendly with the Spanish surrealist painter Joan Miro, and later Paul Klee. Miro’s semi-abstract, euphoric art influenced Calder both formally, and for its sardonic humour.

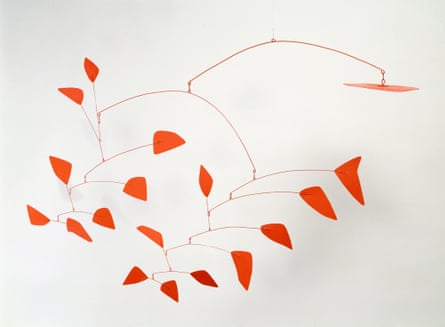

Here Calder designed the first pieces of his hand-operated miniature circus, made up of models with moveable parts. Private performances of Calder’s Circus impressed many avant garde artists and patrons. After a visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio in 1930, he turned to abstraction, and was invited to join the international group Abstraction-Création, along with artists such as Naum Gabo and Wassily Kandinsky. In 1932 he made hand-operated and motorised “mobiles”, the name coined for him by Marcel Duchamp (his stationary sculptures were now called “stabiles”). These mobiles had a cosmic feel, like 3D diagrams of planetary systems, though they equally recall those lugubrious freestanding skeletons displayed in natural history museums.

Calder’s mobiles are streamlined in a recognisably art deco way, and they speak the international language of speed and flight. Yet his works’ origami delicacy means they are often luddite, pastoral rather than industrial. They slow the viewer down, and insist on mild movement and meditation. They were used by Martha Graham in the intervals of her ballets, the dancers replaced by “plastic interludes”, configurations of circles and spirals. Calder also created a mobile set for Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate (1936). In 1943, he explained how viewers should interact with his mobiles, emphasising peaceful coexistence: “A mobile in motion leaves an invisible wake behind it, or rather, each element leaves an individual wake behind its individual self … In setting them in motion by a touch of the hand, consideration should be had for the direction in which the object is designed to move, and for the inertia of the mass involved. A slow gentle impulse, as though one were moving a barge, is almost infallible. In any case, gentle is the word.” When Calder mentions a barge, he must have been thinking back to the stone barge folly in Biscayne Bay, Miami, decorated with mermaid sculptures by his father in 1916.

After the second world war Calder turned his attention to the production of vast stabiles to be placed in corporate lobbies and plazas all over the world. Made from sheet steel, bolted together and brightly painted, these works wrecked his critical reputation and bloated his bank balance. Around 100 of Calder’s early wire works and mobiles will be exhibited at Tate Modern next month. The Tate’s ever increasing investment in performance art, and in art that lends itself to audience interaction may explain its interest in this not-quite-stellar artist. Perhaps we’ll be reminded of Calder’s early subtlety and wit – of what the fuss was once about.

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture is at Tate Modern, London SE1, from 11 November. tate.org.uk. James Hall’s The Self-Portrait: a Cultural History is out in paperback.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion