Andrew Wyeth, who has died aged 91, was America's best-known painter. Even his models became famous just for being his models: one was the subject of a biography, another, his neighbour Helga, was the centre of scandalised speculation because the series of nudes for which she posed seemed so unduly intimate. John Updike, a good judge in these matters, wrote with sly lubriciousness when the paintings of Helga were first shown: "tangled pubic hair... confronts us - affronts us, even - as if still wet from the artist's brush."

But Wyeth was loved by the public for much the same reasons that the rural poet Robert Frost had been, and their careers described a similar trajectory. Both lived to be very old; both were taken up by President Kennedy's administration (Frost read a poem at the Kennedy inauguration in 1961, and Wyeth was awarded the Presidential Medal for Freedom); both won Pulitzer prizes; both were thought, like the movie director John Ford, to encapsulate in their work the essence of old frontier values.

At their best, they did; at his weakest, Wyeth might as well have taken up the offer made in 1943 by the Saturday Evening Post for him to join its stable of cover artists. But he did not want to become an all-American illustrator like the Post's illustrious Norman Rockwell - and he had heard his own father, an illustrator, bemoan choosing the path of mammon rather than the path of virtue, and declined.

Wyeth was the youngest of five children born to NC Wyeth and his wife Carolyn in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvannia. He was a sickly boy, so his parents had him schooled at home, and at the age of 15 he began studying art and illustration with his father. He learnt his lessons well, and had his first exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York at the age of 19, in 1937. Soon after declining the Post's poisoned chalice and choosing instead to pursue a reputation as a fine artist, he was included in the 1943 show at the New York Museum of Modern Art (Moma), American Realists and Magic Realists.

The title describes his activity fairly accurately. He worked in a tradition that might be called American isolationism, and that stretched back to the mid-19th century. It operated quite outside the Impressionist exploration of retinal impressions and the avant-garde movements that followed, and instead rendered appearances with a hyper-realist fidelity impossible in nature, but which gives a heightened sense of the moment and the place depicted. Tellingly, the family home in Maine is called Eight Bells, after a painting by Winslow Homer. Wyeth's nearest contemporary in this mode was Edward Hopper - the urban American in counterpoint to the rural American.

For both Hopper and Wyatt, the broad-brush description of their approach is overly simplistic. Wyeth was quite aware that his reputation among the critics who mattered - who were not the millions who bent the knee to his genius - did not stand high, and he worried away at it, pointing out that his approach to composition involved a large measure of abstraction. So it did, as it must in any half-decent painting. But his reputation suffers most from the suspicion that he was a story-telling artist, and to an extent, because he chose titles straight out of the Victorian age of narrative painting (Witching Hour, Bird in the House, Distant Thunder), he brought this on himself.

Hopper, although he had studied in Paris, declared that American art could stand on its own two feet without help from Europe, thank you very much. Wyeth, who lived all his life between Chadds Ford and Maine, found no difficulty in subscribing to this. No critical storm would ever blow any of his buildings down: his fixtures and fittings fit and are firmly fixed, his windows and doors look as though they would really open and close, his interiors are full of Shaker simplicities.

Shaker simplicity might describe his technique as well: his main medium was tempera, which has egg yolk as an emulsifying agent. It was widely used in the early Renaissance before the brilliance of oils took over, and helps to impart a sense of clarity and simplicity to colour fields. "Tempera is something with which I build," he said, "like building in great layers, the way the earth was itself built."

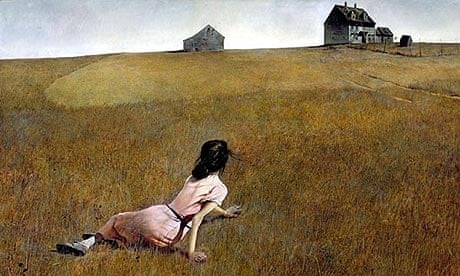

In short, he was a master technician who painted tabletops and window frames, clapboard houses and fruit baskets with the weight and solemnity of the 18th-century French still life artist Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. But Chardin's genius was to paint the objects for the sake of their own weight and density and texture, whereas Wyeth too often tries consciously to reach for the universal beyond the particular, and succeeds only in being windy. His best-known painting, Christina's World (1948), which is owned by Moma, shows a woman sitting in a field with her back to the viewer stretching towards a house on a hill. She was a neighbour of Wyeth's in Maine and had suffered paralysis from polio; her world was circumscribed by the limits of the canvas. Even without that information, the picture is too close to narrative for comfort. But at its best, which is when it is anchored in Chadds Ford or on the seashore in Maine, his painting has visionary power; and painting, after all, has never been a progression from movement to movement, except in art history books.

Wyeth is survived by his wife, Betsy, and his two sons, Nicholas and Jamie (also a painter). In 1998 the Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, Maine, opened a gallery and study centre devoted to the work of NC, Andrew and Jamie Wyeth.

James Kelso writes: The first original work by Andrew Wyeth I encountered was at his one-man show at the Lefevre Gallery in London's Bruton Street in 1974. The magic illusory quality astonished me, and the sheer painting skill of Turner's Mill (1973), a watercolour, took my breath away.

Many critics dismiss Wyeth as a sentimental ruralist. I don't. When there was a major exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy in 1980, I went to it more than 20 times, and the names and location of every picture were fixed in my mind for years. The work got the critical thumbs down. Yet each time I went I saw artists and writers among the crowds poring over the work, and if there was a better 20th-century tempera painter I would like to know his, or her, name. Meanwhile Wyeth's tempera River Cove (1958) hangs in the mansion of my dreams.