Under the lid of a handsome early 19th-century bow-fronted cabinet, in the Hirschsprung museum in Copenhagen, can be found the pile of "oyster shells" that so struck a visitor to the studio of Denmark's most enigmatic painter. They weren't shells: he was describing the build-up of paint on the artist's palette, thick layers of grey on grey.

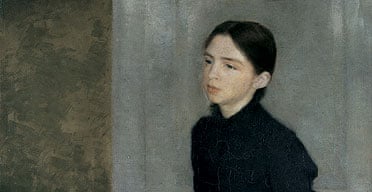

From Vilhelm Hammershøi's first exhibited painting in 1885, a portrait of his sister Anna which created a sensation, to his last works, his colours were mist, fog, cobweb and shadow: grey rooms, grey trees, grey streets emptied of human beings and traffic. When he judged a painting insufficiently grey, he sometimes applied a thin wash across the entire surface.

The creator of these haunting landscapes and interiors was a modest star in his day, but was almost forgotten for half a century after his death. More recently a revival of interest has seen Hammershøi regain his status as one of his country's most original artists, and the first retrospective of his work in Britain opens at the Royal Academy this week. The paintings will travel to Tokyo in the autumn, but while the curators have assembled an unprecedented collection of private and museum loans, they're struggling to illuminate the private man.

To call Hammershøi a quiet painter is a serious understatement: he had few friends and less conversation, and if he ever confided his private thoughts to a diary, he destroyed it. He usually skipped the openings of his own exhibitions. One painting, supposedly of a party at his house, shows some of his best friends gathered in near darkness around a table with a couple of bottles and an empty bowl, apparently in speechless gloom.

His teacher, PS Kroyer - painter of all those colour-saturated images of exquisitely dressed middle-class Danes, strolling along beaches lit by the midnight sun, which have sold a million greeting cards and calendars - recognised a force of nature when he met one: "I don't understand him - I think he will be big, so I try not to influence him."

In 1885, when the Danish Academy refused to give a portrait prize to Hammershøi's painting of his sister Anna, and turned down his next submission, artists got together a furious petition, and Krøyer wrote: "Can we not find a way to blow that whole putrid box up?"

Hammershoi left a thin bundle of spectacularly impersonal letters, and just two notably dry interviews. One explained his technique - "I do not paint fast, I paint fairly slowly"- and one focused bizarrely on interior design: "Personally I am fond of the old; of old houses, of old furniture, of that quite special mood that these things possess."

After his death in 1916, of a throat cancer that silenced the quiet man completely, a friend recalled seeing his palette: "I shall never forget it. There lay four grey and white knobs of paint, meticulously separated from one another. The strange thing was that layer had been laid upon layer of paint, and down inside these layers the paint was strangely smoothed out, so that it looked as if four oyster shells lay on the palette. But with these colours he created the beautiful pictures that I admire."

The palette is in the Hirschprung museum in Copenhagen along with a vast archive donated by Anna, which includes the scrap books Hammershøi's mother kept all her life on her brilliant son.

To his admirers, however, Hammershøi is not grey at all. "This is not a grey room, it is full of subtle colour," says Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, director of the Ordrupgaard museum, smiling at a vast, silvery interior in an 18th-century abandoned palace, an unsigned canvas which she spotted in a pile of paintings in an auction room and bought for her museum.

Felix Kramer, curator of the Academy exhibition, agrees. "So much colour!" he exclaims, peering into the grey-on-grey depths of the artist's depiction of a deserted street behind the British Museum. The painting is in the collection of the Carlsberg Glyptotek, founded by the millionaire brewer Carl Jacobsen, who was one of many wealthy 19th-century Danish industrialists, like Henirich Hirschsprung, who became passionate collectors and bought all the Hammershøis they could lay their hands on.

Comparisons between the paintings and photographs in the archive are intriguing: the young Hammershøi and his brother Svend look jolly enough chaps, but in the paintings have become withdrawn, sullen, as if brooding over some appalling piece of news.

Neither Svend nor Anna ever married, living with their mother for the rest of her life, and together for the rest of theirs - but after the death of both Vilhelm and the formidable mother, Svend's art blossomed. A fascinating exhibition at Øregaard, another beautiful country villa museum in the outskirts of Copenhagen, shows his development from clenched paintings of trees and buildings half-hidden by high walls, to wonderfully sensuous ceramics.

Sidsel Maria Søndergaard, director of Øregaard, is sure that Svend was gay, and wonders about Vilhelm - who did, however, marry Ida, the sister of an art student friend. In scores of paintings she stands in their home, back to the viewer, lost in thought or some interrupted task. The photographs show rooms sparely but not starkly furnished - but in the paintings almost everything is gone, except isolated pieces of oddly positioned furniture. Ida herself has undergone an even greater sea change. The photographs show a nice-looking woman with occasional bad hair days. In the rare paintings when she turns to face the viewer, the impression is shocking: in one she is as green and gaunt as Degas' absinthe drinkers, in another she is stirring a cup of tea - the spoon missing the cup completely - with an expression of stunned desolation.

Ida wrote scores of dutiful letters to her mother-in-law, from their holidays and work visits to London and Paris - but never a hint of opinion about her portrayal.

"I think this exhibition will be a revelation," comments Kramer. "It's not true that Hammershøi just stayed home and painted his living room. These are not grey paintings - there is a lot going on."

· Vilhelm Hammershøi: the Poetry of Silence, Royal Academy London, June 28 - September 7