Never Fading Away: The Pioneering Photography of Henry Peach Robinson

Unwavering in his vision, Henry Peach Robinson was a pioneer of photography and a crucial proponent of accepting it as an art form

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Apr 14, 2023

Henry Peach Robinson was one of England’s most prominent photographers in the latter-half of the 19th century. Utilizing ground-breaking photographic techniques and fighting for the burgeoning medium to be accepted in the art world, Robinson and his pictorial work brazenly challenged the viewer and critic alike, while pioneering photography into what would become its future. He also was no stranger to controversy, with his dramatic tableau of a young girl’s demise creating quite a stir from moralistic Victorian society.

Henry Peach Robinson, She Never Told Her Love, 1857, albumen silver print from glass negative, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Henry Peach Robinson was born in the town of Ludlow, Shropshire, England, on July 9, 1830. At thirteen years old, he undertook a year’s drawing tuition, afterwards going on to become an apprentice to Richard Jones, a bookseller and printer. While continuing to study art, Robinson carved out a career as bookseller, in 1850 working for Bromsgrove-based Benjamin Maund, and the following year for London’s Whittaker & Co. He possessed a precious aptitude for art, exhibiting one of his paintings at the Royal Academy at the age of twenty-one, 1852’s On the Teme Near Ludlow.

But Robinson’s artistry with the brush on canvas soon gave way to what would be his true passion in the art life: photography. The young artist had started taking photographs the same year as he exhibited his oil painting at the RA, and several years later, after a conversation with photographer and psychiatrist Hugh Welch Diamond, made a decision to dedicate himself wholeheartedly to the medium.

This led to the opening of his own photographic studio in Leamington Spa in 1855, where he earned his living carrying out commercial portraiture, and the following year, along with Oscar Gustave Rejlander, was a founding member of the Birmingham Photographic Society.

A great admirer of the Pre-Raphaelites, Robinson began to create photographic pieces that were inspired by the popular paintings of the time. His earliest known work is 1857’s Juliet with the Poison Bottle, which was created by the process known as combination printing, a technique that combines sperate negatives to create a single image, of which Robinson was one of the pioneers.

Robinson possessed a precise vision for his art, and he ensured that the photographs he produced met that vision. He worked mostly in his studio, creating sets and backdrops and utilizing models to create what he saw in his mind’s eye. Actors or society ladies would stand in for peasants in his many bucolic scenes, as he found actual countryfolk lacking his vision of the picturesque ideal. This approach is also reminiscent of the way many painters work, which is not surprising considering Robinson came from a background in the medium.

Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858, combination print, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

The pioneering photographer found himself thrown into infamy in 1858, with the creation of his combination print, Fading Away. Depicting a young girl awaiting an imminent death from consumption, while her mother and sister look on in doomed anticipation, her father turns away from the fated scene in profound sorrow, wiping the tears from his eyes while facing out over a balcony beneath a fittingly overcast sky. The piece is certainly striking, the dramatic effect of the tableau subtly heightened by the heavy curtains which hang in the image’s background, reminiscent of a stage play.

While death was something of an obsession for the Victorians, whose wealthy commonly practiced post-mortem photography, and hung paintings depicting the dead and dying upon their house walls, Robinson’s Fading Away did not garner the response that one might, not-unreasonably, assume. The piece was immediately condemned for delving too deeply into a subject that was immensely personal and private – despite the fact the whole scene was staged. This public reaction stands as a testament to Robinson’s unwavering vision as an artist, for he created a work so poignant, so viscerally striking, that it was treated as if it was an exhibited documentation of an actual death, and not purely artistic vision. However, not all response was of a negative nature, for Prince Albert – an avid amateur photographer himself, ordered a copy, and would go on to purchase other copies of Robinson’s work, and despite the controversary surrounding it, Fading Away also made him the most famous photographer in England.

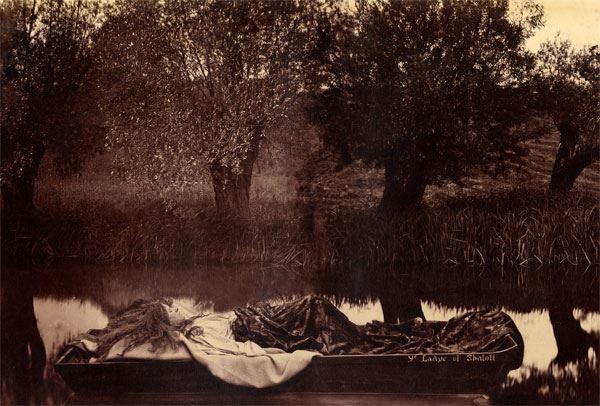

Henry Peach Robinson, The Lady of Shalott, 1861, toned albumen print from two negatives, Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford

Despite the fuss that Fading Away created, Robinson’s subsequent works, such as 1861’s The Lady of Shalott, and 1863’s Autumn, were highly praised by the public. However, Robinson was forced to close his studio in 1864 due to declining health. The years of being exposed to toxic photographic chemicals had taken its toll. He would continue to create his combination prints, but by the ‘scissors and paste-pot’ method as opposed to the more time-consuming darkroom technique. After relocating to London, he turned his efforts once again toward the world of publishing.

In 1869 Robinson published the photographic practice handbook, Pictorial Effect in Photography. This handbook would become the most influential English language work on photographic technique and aesthetics for decades. His subsequent writings on photography were widely distributed and translated, disseminating his artistic vision to the masses. His health now improving, Robinson opened a new photographic studio in Tunbridge Wells, and in 1870, became vice-president of the Royal Photographic Society.

Henry Peach Robinson, When the Day’s Work is Done, 1877, albumen silver print, Getty Center, Los Angeles

Despite his strong advocation that photography be regarded as an art form, in 1886, Pictorial Effect in Photography was vehemently denounced by fellow English photographer Peter Henry Emerson. Emerson, who possessed a more naturalistic view of the medium, was firmly against the practice of altering photographic images post-exposure, as well as Robinson’s penchant for using painted backdrops and costumed models. However, the intellectual attack did little to damage Robinson’s image, for he continued to receive official honors and became a founding member of the prestigious art photographers’ association The Linked Ring in 1892.

Henry Peach Robinson finally faded away himself on the February 21, 1901. Throughout his life he remained dedicated to his particular artistic vision, unwilling to waver to public or professional criticism, or adhere only to previously accepted techniques. This is the mark of the true artist, and as a subsequent result, pieces such as Fading Away remain indisputably impactful 165 years after their initial creation.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

.Jpeg)

.Jpeg)