David Hurn has been an important figure in the British (and international) photographic community for decades. Alongside a successful and widely-published career as a photographer, Hurn also set up the highly renowned School of Documentary Photography in Newport, Wales. In 1989, he left the program to return to his own work.

LensCulture is delighted that he agreed to be a member of the jury for the Magnum Photography Awards 2017. We spoke with Hurn at length over the phone to learn more about his career and his accumulated wisdom from six decades of making photographs. Read on to discover Hurn’s inspiring story and advice for young photographers—

LC: I’ve read that you were inspired to pick up a camera by the photographs of a great Magnum photographer, which opened your eyes to the larger world. Today, we are flooded with images and (seemingly) have access to any knowledge we desire. Do you think photojournalism still holds the same magical power to reveal different worlds that it once had?

DH: I do hope the magic hasn’t gone! I still shoot exactly the same way, operating with the same beliefs that I did when I started. It would have been an incredible waste of 60 years of my life if all of that changed…

I think it’s important to understand the context by which I came to photography. Growing up, I was dyslexic—but there was no such word back then. This meant I did poorly in school and my first dreams—to be an archaeologist or veterinarian—were closed off to me. In the UK at that time, there was compulsory military service. So I went off to the army for 18 months. Mainly because of my prowess at sport, I was invited to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst [the British Army’s officer training center]. I remember, on arrival, noticing that there was a sign over the entrance which said something like, “Enter here and be an officer and a gentleman.” As someone with no qualifications, this seemed like not such a bad idea.

Before (and initially while) I was in the army, I had no thought of becoming a photographer. It never even entered my head as a potential profession. One day, in the officers’ mess hall, I picked up a copy of the Picture Post, a really fine British magazine at the time. I still remember the date: February 12, 1955. I was looking through it and came across a picture—it struck me so forcefully and so immediately, I began to cry. Crying is not something that is normally practiced in the officers’ mess hall at Sandhurst. The photograph featured a Russian army officer buying his wife a hat in a Moscow department store.

It moved me so deeply because my own father had been away from home for the entire Second World War, and my first memory of him with my mother was when he returned and we all went shopping together, as a family. We went to Howell’s, a department store in Cardiff, to buy my mother a hat. That was the moment when, for the first time, I saw the love between my father and mother, saw their shared joy in doing something together. A powerful memory.

Right then, I felt the immense power of photography to create emotion and to seemingly counteract propaganda.

I decided, at that moment, that this is what I wanted to do. Specifically, I wanted to capture the equivalent of people buying hats for their wives. Mundane but special moments, all over the world. Much later, I looked to see who had made the photograph that so moved me. It was an unfamiliar name to me at the time: Henri Cartier-Bresson.

LC: You then began your photographic career as an assistant and freelancer. A breakthrough came when you hitchhiked from London to Budapest to cover the Hungarian revolution (“undertaken as a bit of a lark”). You emerged with historic pictures that launched your career. Right place, right time.

Photography is so much about chance (combined with skill and good timing)—but doesn’t that describe life as well? How do you describe the balance between chance and planning in both your photographic work but also in the way your career has played out?

DH: It’s a really interesting question, isn’t it? Chances happen all throughout our lives—but do we always take them? I suspect not. Of course, oftentimes we don’t realize that the things in front of us are chances, opportunities, waiting to be seized…

The decisions we make in the present moment affect our future—but the context from our earliest years inform these decisions. For example, my mom used to take me to the National Museum in Cardiff on Saturday mornings. My first ever memory, I must have been about five, was of a certain “naughty statue” there. Years later, I realized it was Rodin’s “The Kiss.” Or later, at boarding school, on my wall, I had postcards of Brueghel paintings—images packed with visual detail, as well as careful pattern. I also had photographs of my mom and dad—memories. Aren’t these the building blocks of photography?

All of these things were there, but it took something external—that photograph by Cartier-Bresson—to realize why they had been important to me. Suddenly, it was as though everything came together. The notions of detail, memory, pattern—all were photographic, and all came together in one activity.

Like a blinding flash of light through the window that told me, “You ought to be a photographer.”

LC: Over time, you grew out of photojournalism and preferred to take a more personal approach to photography. Can you say more about this evolution?

DH: I come from a background where work is the honourable basis of what you do. When I went into the army, that was my job; when I came out and decided to be a photographer, I didn’t approach it with vague ideas of “art.” Rather, photography was a job that I did, and of the various genres—wedding, science photography, journalism—the latter seemed the most pertinent to me. Going out and visually recording the world as honestly as you can and showing my observations to others: that’s what I wanted to do.

I discovered one thing instinctively when I moved to London to start my career: if you are a doer, you attract other doers. And if you are a talker, you attract talkers. But the doers are the ones who get on and make it happen. Quickly, then, I found myself in some amazing company—Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, Ian Berry—a great group of contemporaries to learn the craft with (not to mention Ken Russell, Colin Wilson, Paul Foot and more, all of whom expanded my interests to other fields). I learned then that if you are very good at what you do, others will be interested as well, but nobody can steal your ideas, because no one can do it better than you can. For me, that gift was a pursuit of capturing moments in everyday life. This simple goal was what associated me first with Magnum.

One day, I was walking around Trafalgar Square, photographing pigeons very intently. While doing so, I bumped into another man. He said to me, “I think you are a very good photographer.” He suggested that when you look at people who are good at what they do, they have an extraordinary sense of concentration while they’re doing it.

An amateur photographer will flit around, but the person who is concentrating is the one who is really good—the world around becomes blotted out.

And so this man asked to look at my pictures. He told me, “Most of what you’re doing is not your best work. Concentrate on what you do well: everyday life.” At the time, there was little market for those kind of pictures. Still, there was something reassuring in receiving an endorsement to follow my own path. This man then told me he was part of a group called Magnum Photos. I hadn’t heard of them. His name was Sergio Larraín.

It was, of course, good advice. At that time there were few magazines, and they were primarily interested in “current affairs.” Each of my photographer friends had a speciality they excelled at—Don loved anything that raised his adrenaline level, Philip had astute political knowledge, Ian was basically a traveller. I could do these things but was their second best.

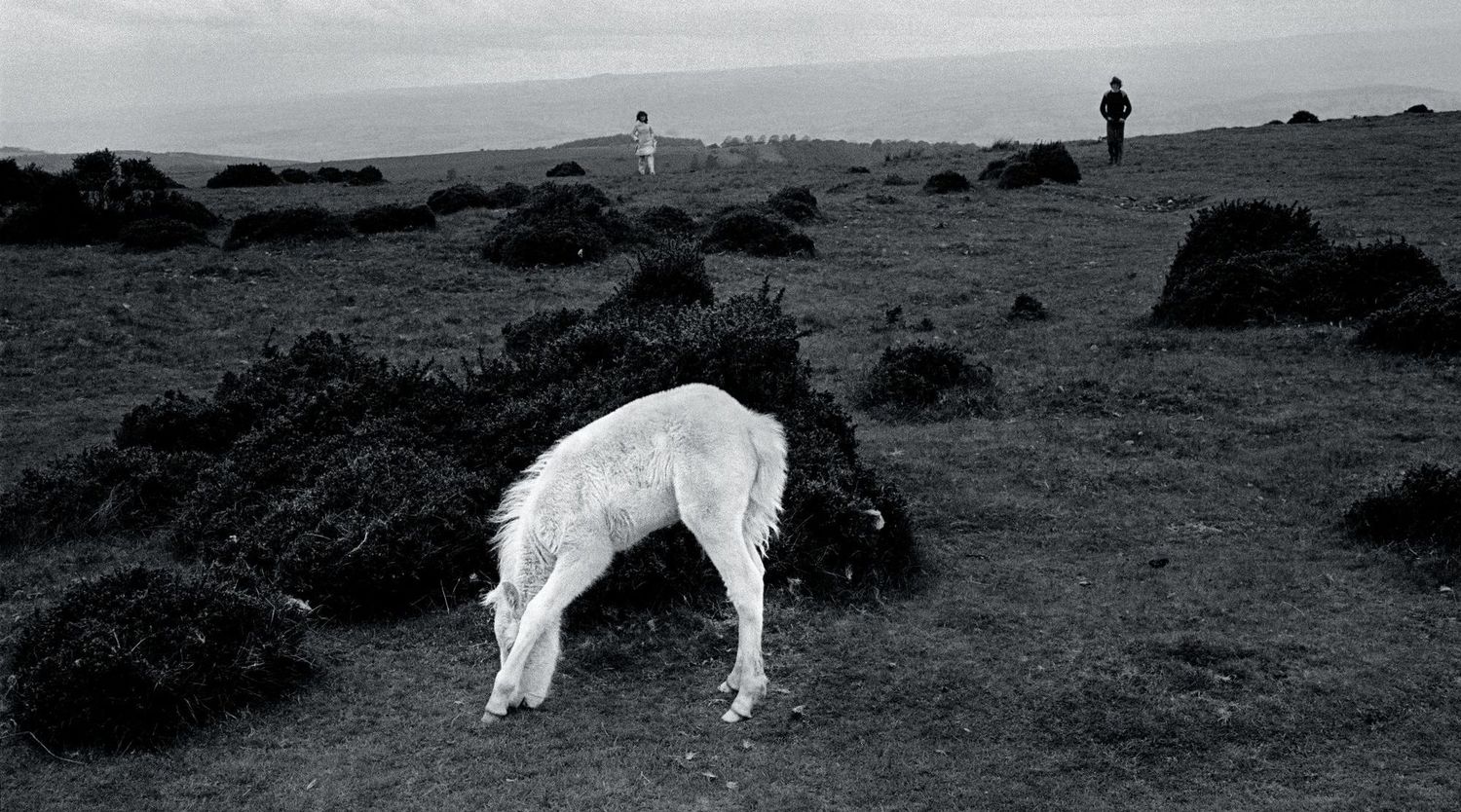

Luckily, in the early 60s, the colour supplements started. Suddenly, there was now a slot for the mundane, and that was one kind of picture that I enjoyed shooting that the others would never shoot—those unexpected moments of levity in the everyday world. So while they were competing over headlines, I was, for example, wandering around Scotland shooting sheep dog trials and getting my work published in an ever-growing market.

My approach to photography is best summarized with a quote. The great essayist Michel Montaigne wrote at the beginning of his collected writings, “I am myself the matter of my book.” Applied to photography, it means that if you are yourself, then something of your particular personality and way of looking at the world will come out in what you do. But you only get there if you genuinely follow your own interests.

So for me, it goes back to a man buying his wife a hat. If you have a clear idea about what interests you in the world and you follow that idea—then you have something, however minor, personal that you do. And if you do something that’s very personal to you, no one else will be able to make the same work.

This applies, by the way, to all the great composers, painters and, of course, photographers. That’s the miracle about photography—we all simply have a box with a hole in the front called a camera. It’s more or less the same for all of us. Yet if you look at 12 pictures by Bresson and 12 by Koudelka and 12 by Frank and 12 by Friedlander, you can instantly see they’re by different people. Isn’t that miraculous?

The greats all have authorship. That’s what we’re looking for—that wonderful uniqueness that shows us something new about the world.

LC: You once said, “I find it unnecessary to create new realities. There is more pleasure, for me, in things as-they-are.” Do you think this notion brings you in conflict with the idea of photography-as-art?

DH: People want to be called artists and I say, “Fine, but what do you mean by that?” I sometimes think it’s used in a way that implies, “I am better than”; I also suspect they think it means more money. Yet many who worked for magazines are now designed as “artists”—think of Bill Brandt, Walker Evans, Cartier-Bresson…all of them worked for magazines and did “jobs” for much of their lives.

In reality, it seems nowadays an artist is anyone a gallery feels they can make money from by putting their work on the walls.

Personally, it happens that the photography I like most comes from when someone goes out and sees the world, recording it as honestly as they can. That’s what I enjoy making and also enjoy looking at: Larraín, Weegee, Koudelka. I am not concerned by what others call it. That’s not to say that there aren’t other genres of photography that can also be wonderful: think of Avedon’s pictures with models and elephants. A fashion photographer sets up every picture, but at least there’s no pretence of reality; he tells you he’s beautifully selling dresses.

For a fine art photographer, it seems to me totally legitimate to set up one’s pictures and call them art. I just ask for transparency, and I don’t want to read three pages of text to justify the pictures. And I don’t want them to decry other genres of photography and impress on the importance of their own work. The various genres of photography are not in competition with each other, and in any case, if you wish to have a competition, I think there are really only two important kinds of photography in contention for the top spot: The first is medical photography, because it saves lives. In 2002, I had cancer, had a colonoscopy and had a certain kind of camera inserted up my backside which saved my life. Those were undoubtedly the most important pictures in the world to me.

The other important pictures are family albums. When someone’s house is on fire or they’re forced to flee their country, very often, the family album is the first thing they think to take. What they’re saying is that the most important thing in their lives are these pictures—they contain memory, love and the images of their loved ones.

LC: And if your house were on fire, and there was a single image from your career that you could save, which would it be?

DH: It’s reasonably simple, actually. My father went into a nursing home not far from where I live, about 20 miles away. I went to see him often and would take pictures when visiting. One time, I went there and as I was leaving, he was sitting in his chair and waved goodbye. He was laughing as he did this—it was a very exaggerated goodbye wave. I would soon discover that he died even before I arrived home.

That picture says to me everything about photography and memory: looking at that picture, I can tell the relationship between him and me and it leaves me with a distinct picture of him—it’s a very positive one.

There’s also a picture which I shot a long time ago, for Holiday magazine, that’s become dear to me. I was asked to convey my idea of mundane Scotland. I went around, looking in the local newspapers for ads to see what was going on. One notice caught my eye for an MG car-owners’ ball. I loved the idea and went along to the gathering. There, I shot a picture of an elderly man, playing with a balloon. It’s so joyous, it gives you so much hope about getting older.

The photo also speaks to me about an essential problem of photography: that you are making an image of another human being. I have always been sensitive to not intrude too much into my subjects’ space. The first thing I do when I look at contact sheets is to cross out pictures which I think are in any way degrading. I am really trying to photograph people as a symbol—in this case, an older man who shows the joys of ageing—but I also remember that they are real people.

Many years after the photograph was published, I received a letter from the man’s wife telling me that he had died. But she also told me that they had seen the picture published time and time again all over the world and each time, it gave them great joy. She then asked if it was possible to get a print of her late husband. It was so lovely to have the thought that the people in my photographs, although I did not try to find out who they were, had really enjoyed being photographed.

—David Hurn, interviewed by Alexander Strecker