Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga Ashkenazi

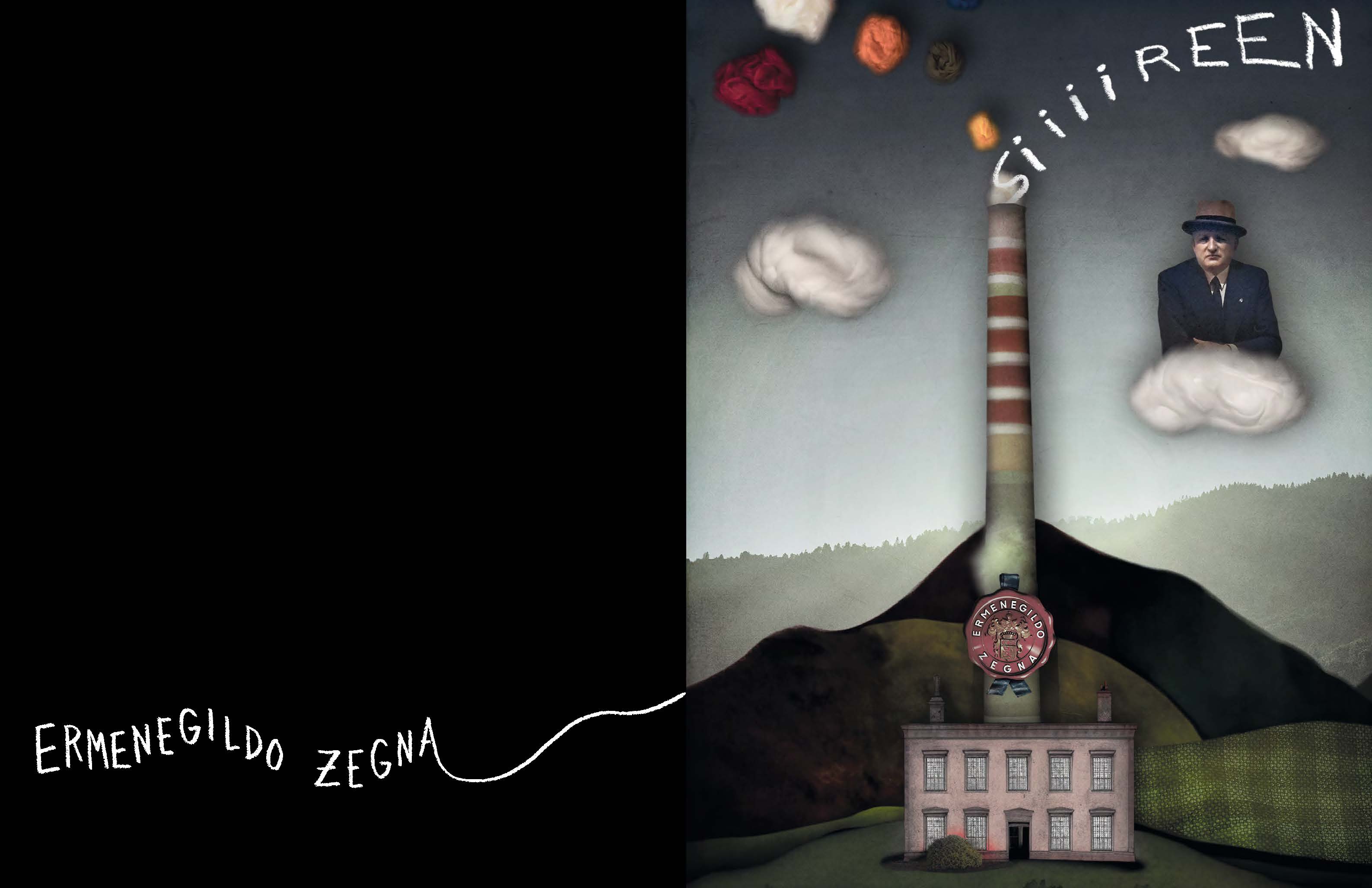

An Effervescent Journey Through Los Angeles With the head of Vionnet

I. It Couldn’t be Helped

I first, properly, meet Goga Ashkenazi—Kazakh-Russian businesswoman and owner/creative director of storied French fashion house, Vionnet—here in her offices in Milan, not far from her home, a four story palazzo stuffed with contemporary art near the luxurious stretch of Via Monte Napoleone. Up to this point, we’ve only shared a handful of suggestive, sidelong glances in the corridors of fashionable parties, clubs, maybe even a pedestrian walkway at some point, each of us in silk scarves. This time it’s a real exchange, though, no deep DC-10 bass to contend with, no approaching ski lift chair, no hoi polloi. Ashkenazi, 36, sports a t-shirt and high-waisted pants (I’m admittedly not the type to spot and report on labels, so I’ll spare you that). But I’ll offer this: she’s braless. It’s nearly summer.

And Ashkenazi is yanking open drawers. They’re full of sketches, sandwiched between plastic sheaths, penciled by Madame Vionnet herself. I learn this is part of a 17,000-piece trove of unseen artifacts Ashkenazi recently acquired from Madame Vionnet’s goddaughter, which beyond the sketches, include photographs, fabrics, embroideries, et cetera. The artifacts depict the innovative, forward, daring cuts the brand became famous for. The bias cut—all sinuous and can-be clingy. And Ashkenazi drapes over each sketch a sort of song of honorary gushing.

This gushing is so upbeat and prophetic that it begs to be read as insincere, but Ashkenazi’s enthusiasm is addictive and it’s apparent there is a genuine love of what she has found herself doing. This observation is amplified, as we quickly jump out of fashion and into contemporary art, namely Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie, whose work is mega-hot-shit at the moment. Ashkenazi cites “The Sunflowers in 1937”—a faux van Gogh, which hawked for a hair over four million dollars, more than five times its estimate, at a Sotheby’s auction in London earlier this year—as example of the demand around Ghenie.

“I think his skill is incredible,” she says. “His knowledge of Goya, Francis Bacon... But he shuts himself off. He doesn’t want to meet anybody. He’s like, ‘I just want to be in my studio and I want to be one-on-one with my creative process. I don’t need to go in and market it.’ It’s like ‘I’m 38, and I’m not ready for that.’ And he doesn’t want to raise his prices, but the works are impossible to get because he’s a huge deal and collectors are snatching them up. And of course, we were having this conversation and he was saying how the prices are somehow damaging his process, because it’s not how a young artist should feel. And I was teasing, of course: ‘Well I think you know us collectors don’t have anything against paying less!’”

So how did Ashkenazi’s prowess as an art collector come to be? Well, before Vionnet—dormant from the end of World War II until 2006, when it was briefly given oxygen by a series of investors who moved it to Milan, and shortly thereafter purchased by the lady in question for an undisclosed sum in 2012—Ashkenazi earned a whole lotta power-paper in oil and gas.

At 26, she became founder and CEO of MunaiGaz-Engineering Group, a K-Zak oil and gas conglomerate and family business, where she and her older sister built compressor stations to serve the country’s tentacular gas pipelines. She became a billionaire very fast.

This success followed a brief role at Merrill Lynch in London, which followed from a degree at Oxford, which followed a youth spent in Soviet Moscow—where her father was an engineer and member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, resided over by some fella called Mikhail Gorbachev. So, at least a few of the requisite boxes for success in the Kazakh oil and gas scene were, suffice it to say, ticked for Ashkenazi. Forget, the boxes though, she sunk her teeth in—and output, and efforts to keep prices low, were not of concern in this instance.

II. Until the Ocean Stops us

II. Until the Ocean Stops us

Far, far from the drab of Milan, I’m enjoying a tumbler of Everclear in the sidecar bar off the lobby of Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, where a string of either the accustomed stroll confidently by and into the courtyard, or the unfamiliar tepidly poke their heads round the corner, as if extras in

Platoon (1986), before entering the grand, vaulted room and asking if the reservation confirmed over the phone wasn’t some kind of sick joke. I’m recalling what Ashkenazi said to me as I departed Vionnet HQ a few months ago. “For me,” she remarked as she planted a kiss on either cheek, “I always describe the Vionnet girl, woman, lady, as somebody that as you walk into the room, you see that she stands out, but not because she is wearing sixteen colors in one outfit, attracting attention or servicing her Instagram account. You see other women and think, ‘Wow, she is beautiful and elegant, her dress is lovely,’ or ‘She is wonderful looking and beautiful and her dress is also lovely’. And then you see my Vionnet girl, but you don’t know how to formulate it even in thought. Something tells you that you want to come to her and you want to ask her questions and you want to have a conversation.”

Into the courtyard parades Ashkenazi, to the nines in her own collection and ready for conversation. She’s trailed by a slightly glistening Simon de Pury, whom

W Magazine has dubbed “the art world’s most controversial auctioneer,” and who’s controversially hoofed it from a relatively deep Beverly Hills locale all the way up the Strip—a journey generally unheard of. Ashkenazi and de Pury, along with de Pury’s wife Michaela Neumeister, have been running all over the Big Orange doing artist studio visits—Jonas Wood, Kathryn Andrews, John Baldessari—they share, as we sit down to a large table that includes other friends of Ashkenazi and

Flaunt.

Following a session of grim-looking calamari, and grimmer looking English people looking over from a corner table, Ashkenazi explains that she came into Vionnet after growing bored of the rigmarole of MunaiGaz. The extreme wealth and the maintenance of that wealth and the territorialism of the resources that made that wealth possible and the number-crunching of wealth to make that wealth last beyond those resources… can be bored-making, I presume. So, where else to go… but to fashion! Where other people’s wealth becomes your livelihood.

“Well, I guess engineering has nothing to do with fashion. Absolutely nothing,” she says of the transition, lightly waving at a friend across the courtyard. “In a way, business is business, and of course I understand numbers better than your usual designer, let’s say. But the main difference is that I get so passionate about the things that I’m making. Let’s say, for example, fabric. My partner would come to me and say, ‘Goga, we cannot buy this fabric because it’s 1,000 euros per meter and we just cannot. I don’t think anybody will ever buy it.’ And I will say, ‘No, I am going to buy it because I love it and it’s completely uneconomical. I mean, I respect money, but what is money when you can make a beautiful piece of art?”

Still, Ashkenazi’s degree at Oxford was in economics (along with history), and the success of MunaiGaz didn’t come with poetic flippancy of resources—rather the opposite. And while seemingly drunk on the ephemeral nature of fashion, she’s not aloof. Ashkenazi tells me she’s always admired the strategic business-making that accompanies that airy form of expression. As a little girl, she recalls,

Vogue would occasionally tumble out of her family’s luggage, and she’d spend hours with the publication. The covers struck her as a reflection of what she did not know at the time to be the competitive culture of beauty outside the then Soviet Union, always with a dreamy and confident attitude. “With Vionnet, I want to get to that place,” she says, as we pocket ourselves beyond the garden’s curtain into the smoking section. “I want to create a dream. I don’t want to be somebody who stitches material and fabric together in bulk. This is not what I’m doing. I’m creating a dream, you know.”

III. Under a Banner of Beverly

III. Under a Banner of Beverly

What are dreams but stirred into the pudding of Hollywood, and so to the Hotel Bel-Air, where Ashkenazi gets some light makeup for her

Flaunt shoot, a romp about L.A. with her pal and occasional Vionnet campaign photographer, Dylan Don. It’s a quiet moment on the veranda and the manicured everything is numbingly beautiful, until the air is pierced with the scream of a yard blower, as it so often is here within supposed sanctuaries, and we look upward at the hazy citrus sky while a helicopter hones in on either a traffic collision, or something similar (but perhaps with humans). And the knife’s edge to that Hollywood dream is symbolically rich.

So it was at first when the fashion set met Ashkenazi, along with her seemingly impulsive purchase of this classic French brand, where, upon her commence, designer twins Barbara and Lucia Croce were quickly dispensed of, though not by Ashkenazi’s initial intent, she shares. Nevertheless, she assumed Creative Director role, did some hiring, inclusive of the acclaimed Hussein Chalayan, and jumped into a collection half-way complete, which meant a crash course in luxury, behind the bar. Her launch saw scrutiny, dismissive of new money trying to play at fashion, and she admitted to the

New York Times’ The Cut last year: “I’m sensitive to what people think of me, because, I admit it, I was tacky at first.”

The initial stings meant carrying forward—in a game filled with, despite its at times brash expression, conservative and thus oft envious, mean people—with the only approach she’s known: study the fuck out of it, and despite emotional sensitivities that would rise up for anyone aiming to create waves in a limited and competitive space, possess and project a fearlessness ready to endure scrutiny until it ceases. Even better yet, surround yourself with solid companions and expertise. “The team at Vionnet have become like a family, and we’re very close,” she says, after a quick glance at her mobile phone. “I trust and rely on them, and of course history—I trust history. I have 75 books full of sketches and fabrics, so many from different collections. We have so many to work with and she created so many unbelievable dresses. Each is a kind of masterpiece in itself and each can tell a story. I mean, last year we did a 1934 collection, which was only pieces taken from the 1934 Vionnet collection.”

As such, Ashkenazi’s collections are gaining momentum, and the reception is warming. While remarking that her FW16 showing in Paris was perhaps a little overwrought, American

Vogue journalist, Luke Leitch, remarked that: “thanks to Ashkenazi, Vionnet today is a house driven by love—a commodity that’s relatively rare on an overwhelmingly cynical schedule.”

IV. Gulliver’s Travails

IV. Gulliver’s Travails

Ashkenazi’s art schedule though, is far from cynical. “I am absolutely fascinated by artistic processes,” she says while arriving at the massive new Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in Downtown L.A., a 100,000 square foot behemoth of urban potentiality, with photographer Don in tow. She’s speaking about the L.A. art scene. “I mean, the George Condo show I saw at Sprüth Magers yesterday, this Hauser and Wirth opening, the Broad Museum opening recently, it is so exciting. And the artists seem to love it. I keep talking about Sterling Ruby because I went to his studio earlier and it had a tremendous effect on me. He was readying a show for Gagosian. I mean, this is what an office should be like!”

We wander the massive space, the former Globe Mills factory complex, which currently hosts the show: Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women: 1947-2016. Having walked the exhibition, we find ourselves at a Russian pierogi food truck in the courtyard, where new restaurant, Manuela, and a garden are being constructed. Ashkenazi continues speaking about the dynamism of Ruby’s art space when she’s interrupted by the vendor. “Do you remember me?” He asks, leaning forward, his Russian accent clear as day. “We met at a nightclub in Moscow!”

“Of course I do!” She politely lies, and he tells her of someone they mutually know in L.A. called Gulliver.

“That was so bizarre,” she says, as we jump in the car to leave downtown. “It’s really funny, and shows how many places in life I’ve been, and how many kinds of lives I’ve lived through. Because whoever he remembered: that was a different version of me.”

There are indeed several versions of Ashkenazi that the tabloids (predominantly UK-centric) seem to gobble up. The businesswomen has spun a sensational web of a social life, be they pals or ex-lovers, that includes some loaded—by association, not bank accounts (though those too)—names, including Colonel Gaddafi’s son, Saif; Fiat heir, Lapo Elkann; Formula One’s Flavio Briatore; and Britain’s own Prince Andrew. A mother of two, Asheknazi’s sons live and are schooled in London, and she sees them on weekends away from Milan. The boys have different daddies, one of whom was born to hotel heir, Stefan Ashkenazy (whose brief hand in marriage and surname she took, the spelling of which was subsequently butchered on her Russian passport, and which she’s kept as such), and the other to fellow oil tycoon Timur Kulibayev—himself married to the daughter of Kazakhstan’s president. I mean, holy shit!

V. They Twinkled and Then They Were Gone

V. They Twinkled and Then They Were Gone

Fortunately, it’s with fashion that a love and expertise of high-flying comrades, hosting dinners, and attending desirable happenings can’t hurt. And while it might seem Ashkenazi is strategically stirring the gossip soup to bolster her caché, the real nature of her social prolifery is this: Ashkenazi is

fun. She’s a riot! It’s no surprise she’s got a ridiculous phone book. And more importantly, she is—in a world with extremely few but still grossly apparent affiliates in every urban hub—a very rich person whose charm perhaps is only superseded by an elegant awareness of the room. I noticed this at the Chateau when she corresponds with the wait staff, telling them a story about her art tours while the very powerful de Pury calmly waits for her to conclude. Perhaps a carry-over from youth? While possessing a staff or being seen to by a staff her whole life, Ashkenazi recalls the understanding that her attendees as a young girl were working for the USSR, and therefore you called them by name, and knew their personal story.

We’ve arrived at filmmaker Albert Kodagolian’s modernist Hollywood Hills home, where 15 or so girls are sequentially baring it all for a “The Girls of Oh La La Land” calendar, included in the sure-to-be award-winning issue in your hands, photographed by curator/editor/photographer/charm snake Olivier Zahm. Like that, Ashkenazi, a friend of Zahm, makes fast pals with Albert’s dog, Stanley, before

Flaunt founder, Luis Barajas, stages a photo with she and the at-work Zahm, creating a unique editorial within an editorial image, and a reminder why

Flaunt is your favorite magazine.

So, it’s by the hand of your favorite magazine that a rowdy group of editors and pin-up girls make for a quick snack at Silver Lake’s Café Stella (known to us as Chateau East)—and the primary venue of the pictorial you see spread over these pages—before stuffing into the once hyper-hip, now moderately problematic, Tenants of the Trees, a bit further East, where she meets “some sort of weird groupie in the bathroom,” among others, and dances to, among others, Asia’s “Heat of the Moment.”

VI. The Writing Was on the Sky

VI. The Writing Was on the Sky

A back-to-earthing the following day at the new Soho property Little Beach House Malibu, where heightened membership regulations versus the WeHo spot, mirror that of the city in which it resides—what the

Hollywood Reporter called “that same occasionally aggressive tribal and territorial instinct that can evince itself in intimidation tactics when, say, outsiders dare to ride preferred waves along the coast.” We’re watching some rightfully due waves and enjoying rosé over ice when the normal absence of that garish skywriting you see above other loved American beaches is broken by the slowly vanishing words trickling over Malibu: “TRUMP IS DISGUSTING.”

I ask Ashkenazi about all her friends, this wild assembly of controversy and beauty and influence—her tribe. She considers this for a moment. “I think,” she finally says, with confidence, “I have been extremely lucky to have met some of the greatest, most talented, and most decent human beings on the planet. Also to be able to choose who I spend my time with. I mean, at a certain point in your life I guess you have a certain number of friends that you don’t always have time for, and so you feel almost like you meet and pay attention to people less. So you create less, because there’s less room for them in your life and scheduling and whatever else. But I always make myself open to new people. And I’m lucky, because of my work, but also the freedom of money I’ve worked like a dog to earn, has made that openness more possible.” Another trail of skywriting above us, presumably a law firm dealing in the representation of injured Latinos all over the Southland. This time: “Justo y Necesario.”

What then, if I’m to attempt translation of this symbol in the sky, is fair? What is just in this world we occupy? Is the answer in fashion? In the mining and distribution of vanishing resources? In the clubs of Hollywood? The pages of art and fashion magazines? The studios and galleries that Ashkenazi’s been bouncing around here in Los Angeles ask this question via painting, photography, sculpture, video, and Ashkenazi is no exception. What is the point? The pace she’s keeping perhaps prevents too hard a look at the extraordinary life she’s living—has lived—this version of herself or another, but it’s that love of the moment, and a curiosity for the new that reminds Ashkenazi, despite her differences from those around her at any given time, she is, without exception, as fleeting to this planet as the descriptive engine exhaust above our pretty heads.

“You know,” she shares, “every person has, I think, another side, which is impossible to understand until you meet them. I hear a lot of people in fashion making that mistake—judging before they’ve even met you. They make opinions, and I think that people should pay attention before forming opinions. It’s the same with art and also the reviewers, and that everybody has a comment. It’s easier than ever to say, ‘Oh I like it, I think that’s great, or that’s not great.’ I think: please go create something yourself and then you can know how it feels to be judged.”

Photographer: Dylan Don for Opus Reps

Hair: Bertrand W. for Opus Beauty

Makeup: Miho Suzuki for Opus Beauty.

Locations: Hotel Bel-Air, Cafe Stella, Tenants of the Trees.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga Ashkenazi

An Effervescent Journey Through Los Angeles With the head of Vionnet

I. It Couldn’t be Helped

I first, properly, meet Goga Ashkenazi—Kazakh-Russian businesswoman and owner/creative director of storied French fashion house, Vionnet—here in her offices in Milan, not far from her home, a four story palazzo stuffed with contemporary art near the luxurious stretch of Via Monte Napoleone. Up to this point, we’ve only shared a handful of suggestive, sidelong glances in the corridors of fashionable parties, clubs, maybe even a pedestrian walkway at some point, each of us in silk scarves. This time it’s a real exchange, though, no deep DC-10 bass to contend with, no approaching ski lift chair, no hoi polloi. Ashkenazi, 36, sports a t-shirt and high-waisted pants (I’m admittedly not the type to spot and report on labels, so I’ll spare you that). But I’ll offer this: she’s braless. It’s nearly summer.

And Ashkenazi is yanking open drawers. They’re full of sketches, sandwiched between plastic sheaths, penciled by Madame Vionnet herself. I learn this is part of a 17,000-piece trove of unseen artifacts Ashkenazi recently acquired from Madame Vionnet’s goddaughter, which beyond the sketches, include photographs, fabrics, embroideries, et cetera. The artifacts depict the innovative, forward, daring cuts the brand became famous for. The bias cut—all sinuous and can-be clingy. And Ashkenazi drapes over each sketch a sort of song of honorary gushing.

This gushing is so upbeat and prophetic that it begs to be read as insincere, but Ashkenazi’s enthusiasm is addictive and it’s apparent there is a genuine love of what she has found herself doing. This observation is amplified, as we quickly jump out of fashion and into contemporary art, namely Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie, whose work is mega-hot-shit at the moment. Ashkenazi cites “The Sunflowers in 1937”—a faux van Gogh, which hawked for a hair over four million dollars, more than five times its estimate, at a Sotheby’s auction in London earlier this year—as example of the demand around Ghenie.

“I think his skill is incredible,” she says. “His knowledge of Goya, Francis Bacon... But he shuts himself off. He doesn’t want to meet anybody. He’s like, ‘I just want to be in my studio and I want to be one-on-one with my creative process. I don’t need to go in and market it.’ It’s like ‘I’m 38, and I’m not ready for that.’ And he doesn’t want to raise his prices, but the works are impossible to get because he’s a huge deal and collectors are snatching them up. And of course, we were having this conversation and he was saying how the prices are somehow damaging his process, because it’s not how a young artist should feel. And I was teasing, of course: ‘Well I think you know us collectors don’t have anything against paying less!’”

So how did Ashkenazi’s prowess as an art collector come to be? Well, before Vionnet—dormant from the end of World War II until 2006, when it was briefly given oxygen by a series of investors who moved it to Milan, and shortly thereafter purchased by the lady in question for an undisclosed sum in 2012—Ashkenazi earned a whole lotta power-paper in oil and gas.

At 26, she became founder and CEO of MunaiGaz-Engineering Group, a K-Zak oil and gas conglomerate and family business, where she and her older sister built compressor stations to serve the country’s tentacular gas pipelines. She became a billionaire very fast.

This success followed a brief role at Merrill Lynch in London, which followed from a degree at Oxford, which followed a youth spent in Soviet Moscow—where her father was an engineer and member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, resided over by some fella called Mikhail Gorbachev. So, at least a few of the requisite boxes for success in the Kazakh oil and gas scene were, suffice it to say, ticked for Ashkenazi. Forget, the boxes though, she sunk her teeth in—and output, and efforts to keep prices low, were not of concern in this instance.

Goga wears Vionnet throughout.

Goga Ashkenazi

An Effervescent Journey Through Los Angeles With the head of Vionnet

I. It Couldn’t be Helped

I first, properly, meet Goga Ashkenazi—Kazakh-Russian businesswoman and owner/creative director of storied French fashion house, Vionnet—here in her offices in Milan, not far from her home, a four story palazzo stuffed with contemporary art near the luxurious stretch of Via Monte Napoleone. Up to this point, we’ve only shared a handful of suggestive, sidelong glances in the corridors of fashionable parties, clubs, maybe even a pedestrian walkway at some point, each of us in silk scarves. This time it’s a real exchange, though, no deep DC-10 bass to contend with, no approaching ski lift chair, no hoi polloi. Ashkenazi, 36, sports a t-shirt and high-waisted pants (I’m admittedly not the type to spot and report on labels, so I’ll spare you that). But I’ll offer this: she’s braless. It’s nearly summer.

And Ashkenazi is yanking open drawers. They’re full of sketches, sandwiched between plastic sheaths, penciled by Madame Vionnet herself. I learn this is part of a 17,000-piece trove of unseen artifacts Ashkenazi recently acquired from Madame Vionnet’s goddaughter, which beyond the sketches, include photographs, fabrics, embroideries, et cetera. The artifacts depict the innovative, forward, daring cuts the brand became famous for. The bias cut—all sinuous and can-be clingy. And Ashkenazi drapes over each sketch a sort of song of honorary gushing.

This gushing is so upbeat and prophetic that it begs to be read as insincere, but Ashkenazi’s enthusiasm is addictive and it’s apparent there is a genuine love of what she has found herself doing. This observation is amplified, as we quickly jump out of fashion and into contemporary art, namely Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie, whose work is mega-hot-shit at the moment. Ashkenazi cites “The Sunflowers in 1937”—a faux van Gogh, which hawked for a hair over four million dollars, more than five times its estimate, at a Sotheby’s auction in London earlier this year—as example of the demand around Ghenie.

“I think his skill is incredible,” she says. “His knowledge of Goya, Francis Bacon... But he shuts himself off. He doesn’t want to meet anybody. He’s like, ‘I just want to be in my studio and I want to be one-on-one with my creative process. I don’t need to go in and market it.’ It’s like ‘I’m 38, and I’m not ready for that.’ And he doesn’t want to raise his prices, but the works are impossible to get because he’s a huge deal and collectors are snatching them up. And of course, we were having this conversation and he was saying how the prices are somehow damaging his process, because it’s not how a young artist should feel. And I was teasing, of course: ‘Well I think you know us collectors don’t have anything against paying less!’”

So how did Ashkenazi’s prowess as an art collector come to be? Well, before Vionnet—dormant from the end of World War II until 2006, when it was briefly given oxygen by a series of investors who moved it to Milan, and shortly thereafter purchased by the lady in question for an undisclosed sum in 2012—Ashkenazi earned a whole lotta power-paper in oil and gas.

At 26, she became founder and CEO of MunaiGaz-Engineering Group, a K-Zak oil and gas conglomerate and family business, where she and her older sister built compressor stations to serve the country’s tentacular gas pipelines. She became a billionaire very fast.

This success followed a brief role at Merrill Lynch in London, which followed from a degree at Oxford, which followed a youth spent in Soviet Moscow—where her father was an engineer and member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, resided over by some fella called Mikhail Gorbachev. So, at least a few of the requisite boxes for success in the Kazakh oil and gas scene were, suffice it to say, ticked for Ashkenazi. Forget, the boxes though, she sunk her teeth in—and output, and efforts to keep prices low, were not of concern in this instance.

II. Until the Ocean Stops us

Far, far from the drab of Milan, I’m enjoying a tumbler of Everclear in the sidecar bar off the lobby of Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, where a string of either the accustomed stroll confidently by and into the courtyard, or the unfamiliar tepidly poke their heads round the corner, as if extras in Platoon (1986), before entering the grand, vaulted room and asking if the reservation confirmed over the phone wasn’t some kind of sick joke. I’m recalling what Ashkenazi said to me as I departed Vionnet HQ a few months ago. “For me,” she remarked as she planted a kiss on either cheek, “I always describe the Vionnet girl, woman, lady, as somebody that as you walk into the room, you see that she stands out, but not because she is wearing sixteen colors in one outfit, attracting attention or servicing her Instagram account. You see other women and think, ‘Wow, she is beautiful and elegant, her dress is lovely,’ or ‘She is wonderful looking and beautiful and her dress is also lovely’. And then you see my Vionnet girl, but you don’t know how to formulate it even in thought. Something tells you that you want to come to her and you want to ask her questions and you want to have a conversation.”

Into the courtyard parades Ashkenazi, to the nines in her own collection and ready for conversation. She’s trailed by a slightly glistening Simon de Pury, whom W Magazine has dubbed “the art world’s most controversial auctioneer,” and who’s controversially hoofed it from a relatively deep Beverly Hills locale all the way up the Strip—a journey generally unheard of. Ashkenazi and de Pury, along with de Pury’s wife Michaela Neumeister, have been running all over the Big Orange doing artist studio visits—Jonas Wood, Kathryn Andrews, John Baldessari—they share, as we sit down to a large table that includes other friends of Ashkenazi and Flaunt.

Following a session of grim-looking calamari, and grimmer looking English people looking over from a corner table, Ashkenazi explains that she came into Vionnet after growing bored of the rigmarole of MunaiGaz. The extreme wealth and the maintenance of that wealth and the territorialism of the resources that made that wealth possible and the number-crunching of wealth to make that wealth last beyond those resources… can be bored-making, I presume. So, where else to go… but to fashion! Where other people’s wealth becomes your livelihood.

“Well, I guess engineering has nothing to do with fashion. Absolutely nothing,” she says of the transition, lightly waving at a friend across the courtyard. “In a way, business is business, and of course I understand numbers better than your usual designer, let’s say. But the main difference is that I get so passionate about the things that I’m making. Let’s say, for example, fabric. My partner would come to me and say, ‘Goga, we cannot buy this fabric because it’s 1,000 euros per meter and we just cannot. I don’t think anybody will ever buy it.’ And I will say, ‘No, I am going to buy it because I love it and it’s completely uneconomical. I mean, I respect money, but what is money when you can make a beautiful piece of art?”

Still, Ashkenazi’s degree at Oxford was in economics (along with history), and the success of MunaiGaz didn’t come with poetic flippancy of resources—rather the opposite. And while seemingly drunk on the ephemeral nature of fashion, she’s not aloof. Ashkenazi tells me she’s always admired the strategic business-making that accompanies that airy form of expression. As a little girl, she recalls, Vogue would occasionally tumble out of her family’s luggage, and she’d spend hours with the publication. The covers struck her as a reflection of what she did not know at the time to be the competitive culture of beauty outside the then Soviet Union, always with a dreamy and confident attitude. “With Vionnet, I want to get to that place,” she says, as we pocket ourselves beyond the garden’s curtain into the smoking section. “I want to create a dream. I don’t want to be somebody who stitches material and fabric together in bulk. This is not what I’m doing. I’m creating a dream, you know.”

II. Until the Ocean Stops us

Far, far from the drab of Milan, I’m enjoying a tumbler of Everclear in the sidecar bar off the lobby of Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, where a string of either the accustomed stroll confidently by and into the courtyard, or the unfamiliar tepidly poke their heads round the corner, as if extras in Platoon (1986), before entering the grand, vaulted room and asking if the reservation confirmed over the phone wasn’t some kind of sick joke. I’m recalling what Ashkenazi said to me as I departed Vionnet HQ a few months ago. “For me,” she remarked as she planted a kiss on either cheek, “I always describe the Vionnet girl, woman, lady, as somebody that as you walk into the room, you see that she stands out, but not because she is wearing sixteen colors in one outfit, attracting attention or servicing her Instagram account. You see other women and think, ‘Wow, she is beautiful and elegant, her dress is lovely,’ or ‘She is wonderful looking and beautiful and her dress is also lovely’. And then you see my Vionnet girl, but you don’t know how to formulate it even in thought. Something tells you that you want to come to her and you want to ask her questions and you want to have a conversation.”

Into the courtyard parades Ashkenazi, to the nines in her own collection and ready for conversation. She’s trailed by a slightly glistening Simon de Pury, whom W Magazine has dubbed “the art world’s most controversial auctioneer,” and who’s controversially hoofed it from a relatively deep Beverly Hills locale all the way up the Strip—a journey generally unheard of. Ashkenazi and de Pury, along with de Pury’s wife Michaela Neumeister, have been running all over the Big Orange doing artist studio visits—Jonas Wood, Kathryn Andrews, John Baldessari—they share, as we sit down to a large table that includes other friends of Ashkenazi and Flaunt.

Following a session of grim-looking calamari, and grimmer looking English people looking over from a corner table, Ashkenazi explains that she came into Vionnet after growing bored of the rigmarole of MunaiGaz. The extreme wealth and the maintenance of that wealth and the territorialism of the resources that made that wealth possible and the number-crunching of wealth to make that wealth last beyond those resources… can be bored-making, I presume. So, where else to go… but to fashion! Where other people’s wealth becomes your livelihood.

“Well, I guess engineering has nothing to do with fashion. Absolutely nothing,” she says of the transition, lightly waving at a friend across the courtyard. “In a way, business is business, and of course I understand numbers better than your usual designer, let’s say. But the main difference is that I get so passionate about the things that I’m making. Let’s say, for example, fabric. My partner would come to me and say, ‘Goga, we cannot buy this fabric because it’s 1,000 euros per meter and we just cannot. I don’t think anybody will ever buy it.’ And I will say, ‘No, I am going to buy it because I love it and it’s completely uneconomical. I mean, I respect money, but what is money when you can make a beautiful piece of art?”

Still, Ashkenazi’s degree at Oxford was in economics (along with history), and the success of MunaiGaz didn’t come with poetic flippancy of resources—rather the opposite. And while seemingly drunk on the ephemeral nature of fashion, she’s not aloof. Ashkenazi tells me she’s always admired the strategic business-making that accompanies that airy form of expression. As a little girl, she recalls, Vogue would occasionally tumble out of her family’s luggage, and she’d spend hours with the publication. The covers struck her as a reflection of what she did not know at the time to be the competitive culture of beauty outside the then Soviet Union, always with a dreamy and confident attitude. “With Vionnet, I want to get to that place,” she says, as we pocket ourselves beyond the garden’s curtain into the smoking section. “I want to create a dream. I don’t want to be somebody who stitches material and fabric together in bulk. This is not what I’m doing. I’m creating a dream, you know.”

III. Under a Banner of Beverly

What are dreams but stirred into the pudding of Hollywood, and so to the Hotel Bel-Air, where Ashkenazi gets some light makeup for her Flaunt shoot, a romp about L.A. with her pal and occasional Vionnet campaign photographer, Dylan Don. It’s a quiet moment on the veranda and the manicured everything is numbingly beautiful, until the air is pierced with the scream of a yard blower, as it so often is here within supposed sanctuaries, and we look upward at the hazy citrus sky while a helicopter hones in on either a traffic collision, or something similar (but perhaps with humans). And the knife’s edge to that Hollywood dream is symbolically rich.

So it was at first when the fashion set met Ashkenazi, along with her seemingly impulsive purchase of this classic French brand, where, upon her commence, designer twins Barbara and Lucia Croce were quickly dispensed of, though not by Ashkenazi’s initial intent, she shares. Nevertheless, she assumed Creative Director role, did some hiring, inclusive of the acclaimed Hussein Chalayan, and jumped into a collection half-way complete, which meant a crash course in luxury, behind the bar. Her launch saw scrutiny, dismissive of new money trying to play at fashion, and she admitted to the New York Times’ The Cut last year: “I’m sensitive to what people think of me, because, I admit it, I was tacky at first.”

The initial stings meant carrying forward—in a game filled with, despite its at times brash expression, conservative and thus oft envious, mean people—with the only approach she’s known: study the fuck out of it, and despite emotional sensitivities that would rise up for anyone aiming to create waves in a limited and competitive space, possess and project a fearlessness ready to endure scrutiny until it ceases. Even better yet, surround yourself with solid companions and expertise. “The team at Vionnet have become like a family, and we’re very close,” she says, after a quick glance at her mobile phone. “I trust and rely on them, and of course history—I trust history. I have 75 books full of sketches and fabrics, so many from different collections. We have so many to work with and she created so many unbelievable dresses. Each is a kind of masterpiece in itself and each can tell a story. I mean, last year we did a 1934 collection, which was only pieces taken from the 1934 Vionnet collection.”

As such, Ashkenazi’s collections are gaining momentum, and the reception is warming. While remarking that her FW16 showing in Paris was perhaps a little overwrought, American Vogue journalist, Luke Leitch, remarked that: “thanks to Ashkenazi, Vionnet today is a house driven by love—a commodity that’s relatively rare on an overwhelmingly cynical schedule.”

III. Under a Banner of Beverly

What are dreams but stirred into the pudding of Hollywood, and so to the Hotel Bel-Air, where Ashkenazi gets some light makeup for her Flaunt shoot, a romp about L.A. with her pal and occasional Vionnet campaign photographer, Dylan Don. It’s a quiet moment on the veranda and the manicured everything is numbingly beautiful, until the air is pierced with the scream of a yard blower, as it so often is here within supposed sanctuaries, and we look upward at the hazy citrus sky while a helicopter hones in on either a traffic collision, or something similar (but perhaps with humans). And the knife’s edge to that Hollywood dream is symbolically rich.

So it was at first when the fashion set met Ashkenazi, along with her seemingly impulsive purchase of this classic French brand, where, upon her commence, designer twins Barbara and Lucia Croce were quickly dispensed of, though not by Ashkenazi’s initial intent, she shares. Nevertheless, she assumed Creative Director role, did some hiring, inclusive of the acclaimed Hussein Chalayan, and jumped into a collection half-way complete, which meant a crash course in luxury, behind the bar. Her launch saw scrutiny, dismissive of new money trying to play at fashion, and she admitted to the New York Times’ The Cut last year: “I’m sensitive to what people think of me, because, I admit it, I was tacky at first.”

The initial stings meant carrying forward—in a game filled with, despite its at times brash expression, conservative and thus oft envious, mean people—with the only approach she’s known: study the fuck out of it, and despite emotional sensitivities that would rise up for anyone aiming to create waves in a limited and competitive space, possess and project a fearlessness ready to endure scrutiny until it ceases. Even better yet, surround yourself with solid companions and expertise. “The team at Vionnet have become like a family, and we’re very close,” she says, after a quick glance at her mobile phone. “I trust and rely on them, and of course history—I trust history. I have 75 books full of sketches and fabrics, so many from different collections. We have so many to work with and she created so many unbelievable dresses. Each is a kind of masterpiece in itself and each can tell a story. I mean, last year we did a 1934 collection, which was only pieces taken from the 1934 Vionnet collection.”

As such, Ashkenazi’s collections are gaining momentum, and the reception is warming. While remarking that her FW16 showing in Paris was perhaps a little overwrought, American Vogue journalist, Luke Leitch, remarked that: “thanks to Ashkenazi, Vionnet today is a house driven by love—a commodity that’s relatively rare on an overwhelmingly cynical schedule.”

IV. Gulliver’s Travails

Ashkenazi’s art schedule though, is far from cynical. “I am absolutely fascinated by artistic processes,” she says while arriving at the massive new Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in Downtown L.A., a 100,000 square foot behemoth of urban potentiality, with photographer Don in tow. She’s speaking about the L.A. art scene. “I mean, the George Condo show I saw at Sprüth Magers yesterday, this Hauser and Wirth opening, the Broad Museum opening recently, it is so exciting. And the artists seem to love it. I keep talking about Sterling Ruby because I went to his studio earlier and it had a tremendous effect on me. He was readying a show for Gagosian. I mean, this is what an office should be like!”

We wander the massive space, the former Globe Mills factory complex, which currently hosts the show: Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women: 1947-2016. Having walked the exhibition, we find ourselves at a Russian pierogi food truck in the courtyard, where new restaurant, Manuela, and a garden are being constructed. Ashkenazi continues speaking about the dynamism of Ruby’s art space when she’s interrupted by the vendor. “Do you remember me?” He asks, leaning forward, his Russian accent clear as day. “We met at a nightclub in Moscow!”

“Of course I do!” She politely lies, and he tells her of someone they mutually know in L.A. called Gulliver.

“That was so bizarre,” she says, as we jump in the car to leave downtown. “It’s really funny, and shows how many places in life I’ve been, and how many kinds of lives I’ve lived through. Because whoever he remembered: that was a different version of me.”

There are indeed several versions of Ashkenazi that the tabloids (predominantly UK-centric) seem to gobble up. The businesswomen has spun a sensational web of a social life, be they pals or ex-lovers, that includes some loaded—by association, not bank accounts (though those too)—names, including Colonel Gaddafi’s son, Saif; Fiat heir, Lapo Elkann; Formula One’s Flavio Briatore; and Britain’s own Prince Andrew. A mother of two, Asheknazi’s sons live and are schooled in London, and she sees them on weekends away from Milan. The boys have different daddies, one of whom was born to hotel heir, Stefan Ashkenazy (whose brief hand in marriage and surname she took, the spelling of which was subsequently butchered on her Russian passport, and which she’s kept as such), and the other to fellow oil tycoon Timur Kulibayev—himself married to the daughter of Kazakhstan’s president. I mean, holy shit!

IV. Gulliver’s Travails

Ashkenazi’s art schedule though, is far from cynical. “I am absolutely fascinated by artistic processes,” she says while arriving at the massive new Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in Downtown L.A., a 100,000 square foot behemoth of urban potentiality, with photographer Don in tow. She’s speaking about the L.A. art scene. “I mean, the George Condo show I saw at Sprüth Magers yesterday, this Hauser and Wirth opening, the Broad Museum opening recently, it is so exciting. And the artists seem to love it. I keep talking about Sterling Ruby because I went to his studio earlier and it had a tremendous effect on me. He was readying a show for Gagosian. I mean, this is what an office should be like!”

We wander the massive space, the former Globe Mills factory complex, which currently hosts the show: Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women: 1947-2016. Having walked the exhibition, we find ourselves at a Russian pierogi food truck in the courtyard, where new restaurant, Manuela, and a garden are being constructed. Ashkenazi continues speaking about the dynamism of Ruby’s art space when she’s interrupted by the vendor. “Do you remember me?” He asks, leaning forward, his Russian accent clear as day. “We met at a nightclub in Moscow!”

“Of course I do!” She politely lies, and he tells her of someone they mutually know in L.A. called Gulliver.

“That was so bizarre,” she says, as we jump in the car to leave downtown. “It’s really funny, and shows how many places in life I’ve been, and how many kinds of lives I’ve lived through. Because whoever he remembered: that was a different version of me.”

There are indeed several versions of Ashkenazi that the tabloids (predominantly UK-centric) seem to gobble up. The businesswomen has spun a sensational web of a social life, be they pals or ex-lovers, that includes some loaded—by association, not bank accounts (though those too)—names, including Colonel Gaddafi’s son, Saif; Fiat heir, Lapo Elkann; Formula One’s Flavio Briatore; and Britain’s own Prince Andrew. A mother of two, Asheknazi’s sons live and are schooled in London, and she sees them on weekends away from Milan. The boys have different daddies, one of whom was born to hotel heir, Stefan Ashkenazy (whose brief hand in marriage and surname she took, the spelling of which was subsequently butchered on her Russian passport, and which she’s kept as such), and the other to fellow oil tycoon Timur Kulibayev—himself married to the daughter of Kazakhstan’s president. I mean, holy shit!

V. They Twinkled and Then They Were Gone

Fortunately, it’s with fashion that a love and expertise of high-flying comrades, hosting dinners, and attending desirable happenings can’t hurt. And while it might seem Ashkenazi is strategically stirring the gossip soup to bolster her caché, the real nature of her social prolifery is this: Ashkenazi is fun. She’s a riot! It’s no surprise she’s got a ridiculous phone book. And more importantly, she is—in a world with extremely few but still grossly apparent affiliates in every urban hub—a very rich person whose charm perhaps is only superseded by an elegant awareness of the room. I noticed this at the Chateau when she corresponds with the wait staff, telling them a story about her art tours while the very powerful de Pury calmly waits for her to conclude. Perhaps a carry-over from youth? While possessing a staff or being seen to by a staff her whole life, Ashkenazi recalls the understanding that her attendees as a young girl were working for the USSR, and therefore you called them by name, and knew their personal story.

We’ve arrived at filmmaker Albert Kodagolian’s modernist Hollywood Hills home, where 15 or so girls are sequentially baring it all for a “The Girls of Oh La La Land” calendar, included in the sure-to-be award-winning issue in your hands, photographed by curator/editor/photographer/charm snake Olivier Zahm. Like that, Ashkenazi, a friend of Zahm, makes fast pals with Albert’s dog, Stanley, before Flaunt founder, Luis Barajas, stages a photo with she and the at-work Zahm, creating a unique editorial within an editorial image, and a reminder why Flaunt is your favorite magazine.

So, it’s by the hand of your favorite magazine that a rowdy group of editors and pin-up girls make for a quick snack at Silver Lake’s Café Stella (known to us as Chateau East)—and the primary venue of the pictorial you see spread over these pages—before stuffing into the once hyper-hip, now moderately problematic, Tenants of the Trees, a bit further East, where she meets “some sort of weird groupie in the bathroom,” among others, and dances to, among others, Asia’s “Heat of the Moment.”

V. They Twinkled and Then They Were Gone

Fortunately, it’s with fashion that a love and expertise of high-flying comrades, hosting dinners, and attending desirable happenings can’t hurt. And while it might seem Ashkenazi is strategically stirring the gossip soup to bolster her caché, the real nature of her social prolifery is this: Ashkenazi is fun. She’s a riot! It’s no surprise she’s got a ridiculous phone book. And more importantly, she is—in a world with extremely few but still grossly apparent affiliates in every urban hub—a very rich person whose charm perhaps is only superseded by an elegant awareness of the room. I noticed this at the Chateau when she corresponds with the wait staff, telling them a story about her art tours while the very powerful de Pury calmly waits for her to conclude. Perhaps a carry-over from youth? While possessing a staff or being seen to by a staff her whole life, Ashkenazi recalls the understanding that her attendees as a young girl were working for the USSR, and therefore you called them by name, and knew their personal story.

We’ve arrived at filmmaker Albert Kodagolian’s modernist Hollywood Hills home, where 15 or so girls are sequentially baring it all for a “The Girls of Oh La La Land” calendar, included in the sure-to-be award-winning issue in your hands, photographed by curator/editor/photographer/charm snake Olivier Zahm. Like that, Ashkenazi, a friend of Zahm, makes fast pals with Albert’s dog, Stanley, before Flaunt founder, Luis Barajas, stages a photo with she and the at-work Zahm, creating a unique editorial within an editorial image, and a reminder why Flaunt is your favorite magazine.

So, it’s by the hand of your favorite magazine that a rowdy group of editors and pin-up girls make for a quick snack at Silver Lake’s Café Stella (known to us as Chateau East)—and the primary venue of the pictorial you see spread over these pages—before stuffing into the once hyper-hip, now moderately problematic, Tenants of the Trees, a bit further East, where she meets “some sort of weird groupie in the bathroom,” among others, and dances to, among others, Asia’s “Heat of the Moment.”

VI. The Writing Was on the Sky

A back-to-earthing the following day at the new Soho property Little Beach House Malibu, where heightened membership regulations versus the WeHo spot, mirror that of the city in which it resides—what the Hollywood Reporter called “that same occasionally aggressive tribal and territorial instinct that can evince itself in intimidation tactics when, say, outsiders dare to ride preferred waves along the coast.” We’re watching some rightfully due waves and enjoying rosé over ice when the normal absence of that garish skywriting you see above other loved American beaches is broken by the slowly vanishing words trickling over Malibu: “TRUMP IS DISGUSTING.”

I ask Ashkenazi about all her friends, this wild assembly of controversy and beauty and influence—her tribe. She considers this for a moment. “I think,” she finally says, with confidence, “I have been extremely lucky to have met some of the greatest, most talented, and most decent human beings on the planet. Also to be able to choose who I spend my time with. I mean, at a certain point in your life I guess you have a certain number of friends that you don’t always have time for, and so you feel almost like you meet and pay attention to people less. So you create less, because there’s less room for them in your life and scheduling and whatever else. But I always make myself open to new people. And I’m lucky, because of my work, but also the freedom of money I’ve worked like a dog to earn, has made that openness more possible.” Another trail of skywriting above us, presumably a law firm dealing in the representation of injured Latinos all over the Southland. This time: “Justo y Necesario.”

What then, if I’m to attempt translation of this symbol in the sky, is fair? What is just in this world we occupy? Is the answer in fashion? In the mining and distribution of vanishing resources? In the clubs of Hollywood? The pages of art and fashion magazines? The studios and galleries that Ashkenazi’s been bouncing around here in Los Angeles ask this question via painting, photography, sculpture, video, and Ashkenazi is no exception. What is the point? The pace she’s keeping perhaps prevents too hard a look at the extraordinary life she’s living—has lived—this version of herself or another, but it’s that love of the moment, and a curiosity for the new that reminds Ashkenazi, despite her differences from those around her at any given time, she is, without exception, as fleeting to this planet as the descriptive engine exhaust above our pretty heads.

“You know,” she shares, “every person has, I think, another side, which is impossible to understand until you meet them. I hear a lot of people in fashion making that mistake—judging before they’ve even met you. They make opinions, and I think that people should pay attention before forming opinions. It’s the same with art and also the reviewers, and that everybody has a comment. It’s easier than ever to say, ‘Oh I like it, I think that’s great, or that’s not great.’ I think: please go create something yourself and then you can know how it feels to be judged.”

VI. The Writing Was on the Sky

A back-to-earthing the following day at the new Soho property Little Beach House Malibu, where heightened membership regulations versus the WeHo spot, mirror that of the city in which it resides—what the Hollywood Reporter called “that same occasionally aggressive tribal and territorial instinct that can evince itself in intimidation tactics when, say, outsiders dare to ride preferred waves along the coast.” We’re watching some rightfully due waves and enjoying rosé over ice when the normal absence of that garish skywriting you see above other loved American beaches is broken by the slowly vanishing words trickling over Malibu: “TRUMP IS DISGUSTING.”

I ask Ashkenazi about all her friends, this wild assembly of controversy and beauty and influence—her tribe. She considers this for a moment. “I think,” she finally says, with confidence, “I have been extremely lucky to have met some of the greatest, most talented, and most decent human beings on the planet. Also to be able to choose who I spend my time with. I mean, at a certain point in your life I guess you have a certain number of friends that you don’t always have time for, and so you feel almost like you meet and pay attention to people less. So you create less, because there’s less room for them in your life and scheduling and whatever else. But I always make myself open to new people. And I’m lucky, because of my work, but also the freedom of money I’ve worked like a dog to earn, has made that openness more possible.” Another trail of skywriting above us, presumably a law firm dealing in the representation of injured Latinos all over the Southland. This time: “Justo y Necesario.”

What then, if I’m to attempt translation of this symbol in the sky, is fair? What is just in this world we occupy? Is the answer in fashion? In the mining and distribution of vanishing resources? In the clubs of Hollywood? The pages of art and fashion magazines? The studios and galleries that Ashkenazi’s been bouncing around here in Los Angeles ask this question via painting, photography, sculpture, video, and Ashkenazi is no exception. What is the point? The pace she’s keeping perhaps prevents too hard a look at the extraordinary life she’s living—has lived—this version of herself or another, but it’s that love of the moment, and a curiosity for the new that reminds Ashkenazi, despite her differences from those around her at any given time, she is, without exception, as fleeting to this planet as the descriptive engine exhaust above our pretty heads.

“You know,” she shares, “every person has, I think, another side, which is impossible to understand until you meet them. I hear a lot of people in fashion making that mistake—judging before they’ve even met you. They make opinions, and I think that people should pay attention before forming opinions. It’s the same with art and also the reviewers, and that everybody has a comment. It’s easier than ever to say, ‘Oh I like it, I think that’s great, or that’s not great.’ I think: please go create something yourself and then you can know how it feels to be judged.”

.jpg)