A selection of architects give their views of the emerging Unite d’Habitation by Le Corbusier

Originally published in AR May 1951, this piece was republished online in July 2016

Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles has been more disagreed about than any other building going up anywhere since the war-besides being the subject of wilder rumours. As a fair sample of the diverse opinions which informed observers maintain about it, here is a discussion held recently by members of the Housing Division of the London County Council Architect’s Department and their guests; it serves as introduction to a full account of the building which will be published later, and as a further contribution to the venture into architectural criticism which was launched last month. It will be seen that, however much speakers differed about the social and structural aspects of the Unite d’Habitation, about its aesthetic qualities-and in particular, curiously enough, the ‘humanity’ of its scale-there was no disagreement at all.

Looking toward the partly finished structure of the gymnasium on the roof of the Unite d’Habitation. The photographs brings out with particular clarity the close relationship between Le Corbusier’s painting and buildings.

Looking toward the partly finished structure of the gymnasium on the roof of the Unite d’Habitation. The photographs brings out with particular clarity the close relationship between Le Corbusier’s painting and buildings.

Kenneth Easton

At the end of the war the Marseilles Municipality commissioned Le Corbusier to help them solve their housing problem and in doing this presented him with a full-scale op ortunity of realizing the ideas of a lifetime-the design and erection of a vertical garden city. After 25 years of paper planning and production of evolutionary projects, Unite d’Habitation No.1 has taken shape and is now nearing completion. This building and the ideas behind it have probably engendered more heat ‘for and against’ than any other building since the war and it is our purpose here to invite first-hand reports from six architects who have recently made the pilgrimage to Marseilles. My contribution therefore must be broad and brief.

Before going to Marseilles I had collected some general information about the four sites, the seven governments and the three contractors who had gone down during the progress of building and I had pored over and speculated upon the published information and the progress photographs that were available. It seemed to me that this elegant rectangle raised up on pilotis, housing 1,600 people in two-storeyed flats and providing most of the amenities of a neighbourhood unit, was clearly the fusion of ideas of two men-Corbusier the social philosopher and Corbusier the modern romantic architect.

‘Doing this presented him with a full-scale opportunity of realizing the ideas of a lifetime.’

It seemed clear too that the complete integration of 293 structure and form and the high degree of standardization should fulfil Corbusier’s claims that the building would be speedily and economically built; the vague reports that work was rather slow and that costs were mounting alarmingly seemed difficult to credit. The internal planning itself, the thin slices of double-storeyed living accommodation 12 feet wide and 60 feet long, lit only at the ends, and served only by internal roads, artificially lit and ventilated, seemed more doubtful, and this sort of doubt struck at the whole economic conception of planning vertical houses.

However, as a background to the building I decided to first take stock of Marseilles and the Marseillais.

The second city of France, and surely her first for noise and perpetual bustle, is Mediterranean rather than French in its way of life. Its vigorous and multitudinous inhabitants, a fifth of whom I believe are Italian, live, eat, shop, and carry out their business in the open air along the wide boulevards of their busy canebiere and around the picturesque harbour and horseshoe of sunny quays of the Vielle Port.

How, I wondered, could 1,600 of this essentially ‘agora-minded’ and volatile community ever be happily contained in this great rectangle on the outskirts of the town? Mixed feelings, however, do leave one with an open mind and it was in this state that I boarded the tram which left the boulevards and the high buildings of the town behind, passed the stadium and the villas dotted among the eucalyptus and olive trees of the outskirts and fetched up level with a contractor’s board announcing that this was ‘Unite d’Habitation No.1’ and that Le Corbusier was the architect. (Two facts which, by the way, are known to everyone in Marseilles.)

‘How, I wondered, could 1,600 of this essentially ‘agora-minded’ and volatile community ever be happily contained in this great rectangle on the outskirts of the town?’

At first sight the building looks deceptively small, the seventeen storeys sitting on the truly heroic pilotis seems a masterpiece of deliberate understatement. Scale, the treatment of planes, patterns and surfaces are as magnificent as the bad finish of the precast concrete work is deplorable. Both inside and out-and this includes the jeu d’ esprit on the roof-I found a building which was always interesting and often exciting. The demonstration flat which is completed and furnished makes magnificent use of its 1,000 square feet (costing about £1,100 before devaluation) and has excellent services and equipment.

‘I found a building which was always interesting and often exciting.’

Of course if you are not wildly enthusiastic during or immediately after a visit to any Corbusier building it is unlikely that you ever will be, and later, after I had left the site and had recovered myself physically and mentally, I found some doubts, which are summarized in the following questions, still persisting.

1. Does the whole approach and conception of Unite give us the sort of building which can properly fulfil our current sociological functions?

2. Have the full benefits of such a scheme been curtailed by limiting it to one block instead of to a group of blocks?

3. Will the final capital cost make it a failure in quite another way by demanding rentals which are too high for the people for whom it has been designed?

4. Is this the beginning of vertical housing in concentrated densities and if so is it a solution which we can accept and agree to develop in this country?

I shall not attempt to answer these questions now but simply throw them out for discussion.

Moholi and King

Although Unite is on a monumental scale it should not be regarded only for its architectural features. It is the culmination of twenty-six years’ study urban development, and its sociological perhaps more important to planners than its architectural conception. Indeed its architecture is the physical expression of certain sociological precepts.

‘Its architecture is the physical expression of certain sociological precepts.’

For the first time Le Corbusier is now executing the ideas which he has for so long propounded in his writings. And like all great artists he has in many respects relied on intuition rather than scientific method and analysis in order to create a building which will fulfil its anticipated social functions.

These sketch plans and elevations afford a means of relating the Marseilles flat of two London schemes.

These sketch plans and elevations afford a means of relating the Marseilles flat of two London schemes.

The Unite must not be considered as the ultimate realization since it is proposed to be the first of a number, which will then comprise his long cherished dream of une cite-jardin verticale. Its name is a guide to its accommodation, since it is designed for the social life of a small community. In addition to 330 flats for 1,600 people (at a density of 139 to the acre) it will contain a post office, a shopping centre on the 7th and 8th floors, a library and restaurant, an hotel for guests, clubrooms, a clinic on the top floor and a running-track and gymnasium on the roof; while a swimming-bath and a school are sited in the 11,5 acre grounds surrounding the building. These, by contrast in size, will provide a foil to the architectural mass of the building.

Perhaps a comparison between Unite and one of London’s largest blocks of flats will help to clarify some of the more tangible town-planning factors involved. Dolphin Square, Westminster, is one of the most ‘luxurious’ blocks of flats erected during the inter-war period; designed as a quadrangle, its multi-storeys enclose an area laid out with gardens, terraces and tennis courts, and cater for different sized families. It has its own restaurants, dance hall, laundry, gymnasia and squash courts. The whole conception aims to provide a social refuge from the immensity of London. Occupying a site of 71/4 acres, its population density is 415 persons an acre, a figure that far exceeds the maximum density of 200 persons an acre for London advocated in the County of London Plan. Although this figure is considerably greater than the density of the Unite d’Habitation (139 per acre) can we truthfully say that Dolphin Square has a closer resemblance to a beehive than Unite? A balanced judgment can only be made when other Unites have been erected and occupied for some years, and I therefore leave the issue as a matter for your conjecture. (Further interesting density comparisons are the proposed LCC development at Princes Way, Wimbledon, where 1,600 people are to be housed in an ‘open’ park site of 27 acres and the residential area of Lansbury (Poplar and Stepney): 12 acres, 1,500 persons, 125 per acre.)

These sketch plans and elevations afford a means of relating the Marseilles flat of two London schemes. The First, Dolphin Square, Westminster, reputed to be the largest block of flats in Europe. This has a total population of 3,000 people as against 1.600 people in the Unite d’Habitation and 1,500 in the second comparative example, part of the Lansbury neighbourood, East Lonson, which is now under construction.

These sketch plans and elevations afford a means of relating the Marseilles flat of two London schemes. The First, Dolphin Square, Westminster, reputed to be the largest block of flats in Europe. This has a total population of 3,000 people as against 1.600 people in the Unite d’Habitation and 1,500 in the second comparative example, part of the Lansbury neighbourood, East Lonson, which is now under construction.

Perhaps a comparison between Unite and one of London’s largest blocks of flats will help to clarify some of the more tangible town-planning factors involved. Dolphin Square, Westminster, is one of the most ‘luxurious’ blocks of flats erected during the inter-war period; designed as a quadrangle, its multi-storeys enclose an area laid out with gardens, terraces and tennis courts, and cater for different sized families. It has its own restaurants, dance hall, laundry, gymnasia and squash courts. The whole conception aims to provide a social refuge from the immensity of London. Occupying a site of 71/4 acres, its population density is 415 persons an acre, a figure that far exceeds the maximum density of 200 persons an acre for London advocated in the County of London Plan.

Although this figure is considerably greater than the density of the Unite d’Habitation (139 per acre) can we truthfully say that Dolphin Square has a closer resemblance to a beehive than Unite? A balanced judgment can only be made when other Unites have been erected and occupied for some years, and I therefore leave the issue as a matter for your conjecture. (Further interesting density comparisons are the proposed LCC development at Princes Way, Wimbledon, where 1,600 people are to be housed in an ‘open’ park site of 27 acres and the residential area of Lansbury (Poplar and Stepney): 12 acres, 1,500 persons, 125 per acre.)

The second comparative example, part of the Lansbury neighbourood, East Lonson, which is now under construction.

The second comparative example, part of the Lansbury neighbourood, East Lonson, which is now under construction.

Max Gooch

In explaining the structure (which is my contribution to this symposium) the clearest way is to start from the individual flat and work outwards.

With 1,600 persons closely packed into one block, sound insulation obviously becomes a major problem, and this has probably been the greatest single factor influencing Le Corbusier’s structural design. Each flat is a box, complete in itself, made up of light prefabricated panels of dry construction whose dimensions are based on the Modulor. These boxes are assembled inside the structural frame, but do not touch it directly. They rest on joists of pressed steel spanning between the main frames, but insulated from them by pads of lead.

‘It is said that Le Corbusier spent several months arriving at the exact form for the pilotis.’

The main structure of the block is of in situ reinforced concrete, and the shuttering for this is quite crude, being knocked together from rough timber. There is no use of standard metal moulds as one might have expected. However, the concrete comes out remarkably clean. Only at every third floor is there a solid concrete slab, to provide a fire-break. The intermediate floors are of the same type of dry construction. Outside the main frame the floor slabs cantilever to form balconies, and on these stands the exterior cladding of precast slabs and grilles. The rough finish of these precast elements has surprised some people familiar with the precision of the Pavilion Suisse, but I think this is quite deliberate, and that Corbusier realized that an assemblage of smooth precise slabs on this scale would be intolerable, a point borne out, in my opinion, by some recent American office-blocks. On the in situ work of the ground floor too the board marks are clearly shown (beton brut), and all this seems to me a great contribution to the architectural handling of concrete.

The main structural frame, seventeen storeys high, stands on the sel artifficiel- the classical Corbusier device as used in the Pavilion Suisse-some 30 feet above the natural ground. This massive slab collects the point loads from the closely spaced columns above and transmits them to the huge portal-framed pilotis. As an example of the careful study which Corbusier gives to form it is said that he spent several months arriving at the exact form for these pilotis, and in his Paris office is a precise model of one of them in plaster, about five feet high.

One of the massive pilotis which carry the whole load of the seventeen storey building, and house various pipes and mechanical services in their thickness.

One of the massive pilotis which carry the whole load of the seventeen storey building, and house various pipes and mechanical services in their thickness.

Thurston William

What I have to say is entirely impromptu-an attempt to recall certain immediate personal sensations on visiting the site. In the first place I was impressed by the fact that Unite seemed less vast than I had expected; this is probably due to the excellent proportioning of the building (though how far this in turn is due to the Modulor I would not like to say). The use of strong colour in the reveals of the balconies is perhaps a bit violent but when the whole building is completed in this manner we will be able to judge better whether this use of colour has achieved its object which is presumably to lighten the dead character of so much exposed concrete.

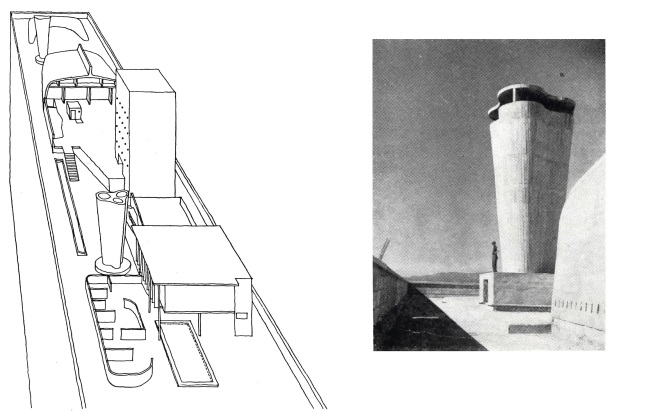

The south end of the roof with the solarium on the left and the structural framework of the cafeteria beyond. Below the vent is an open-air garden for children, surrounded by low walls and visible in the drawning.

The south end of the roof with the solarium on the left and the structural framework of the cafeteria beyond. Below the vent is an open-air garden for children, surrounded by low walls and visible in the drawning.

Generally speaking one would say that the aesthetic quality of the conception is beyond dispute; the photographs here will enlarge upon that better than I can. But in execution the performance falls rather short, the constructional methods being almost mediaeval in their crudity. This is particularly unfortunate where the reinforced concrete so handled is left exposed. My own criticisms, however, are of a more sociological character. Firstly, the attempt at completeness made by the inclusion of shops, post office, library, clinic, etc., within one single building must be a limitation to the social life of the inhabitants; one can well imagine that the housewife will have little need and less inclination ever to leave the building at all for days on end. And this seems particularly unfitting to the temperament of such people as the Marseillais. The conception seems to dominate rather than to liberate.

Then vent at the north end of the roof with one wall of the gymnasium of the right.

Then vent at the north end of the roof with one wall of the gymnasium of the right.

Looking up the inside of one of the vents.

Looking up the inside of one of the vents.

Finally, there are those rumours about rising cost of the project; and unless the final rentals are within the reach of the workers for whom it was originally planned, it will have failed in its principal objective.

W. G. Howell

I don’t think it is possible to understand the Unite as a contribution to urban architecture if it is considered merely in its present isolated setting.

When Corbusier was called in to build apartments for the Marseilles Municipality, no plan of development for the city existed, and the lack of any such plan is reflected in the chaotic rebuilding in the old port. It is unlikely that anything built in an unplanned milieu can produce out of the blue a patch of balanced urbanism. ·Therefore I suggest that, in discussing this aspect of the project, we examine it as it is used in the plan for St. Die.

Le Corbusier’s plan for St. Die in the Vosges, with its eight blocks of flats on the same principles as Marseilles, linked by pedestrians ways leading to the town centre.

Le Corbusier’s plan for St. Die in the Vosges, with its eight blocks of flats on the same principles as Marseilles, linked by pedestrians ways leading to the town centre.

This post-war project by Corbusier for rebuilding a small town in the Vosges represents the most recent development of his ideas on urbanism. In the plan, Corbusier shows eight Unites, closely related to broad pedestrian ways leading into and through a series of ‘piazzas’, from which runs another broad pedestrian route across the river to a place d’industrie, the centre of gravity of a group of factories which stretch along the river-bank. All vehicular traffic is isolated on different levels.

The eight Unites form a series of vertical streets within a few minutes’ walk of the town centre, and are set in a landscaped park with schools disposed around them. Then, from this highly concentrated centre (something like 250 people to the acre), long ribbons of low houses run out into the countryside along parkways, which are separated from the main approach roads to the town. These two, the vertical street related to the piazza and the horizontal street radiating into the countryside, are clearly differentiated in the plan, each an imaginative interpretation of a particular way of living.

‘This post-war project by Corbusier for rebuilding a small town in the Vosges represents the most recent development of his ideas on urbanism.’

The only reservation I would make here is that I would like to see a higher proportion of houses-in St. Die the proportion is three persons in flats to every one in the houses, though there seem to be provisional sites for more houses.

Bearing in mind this setting one may discount Thurston Williams’s fear that there would be no incentive for the housewife ever to leave the building. What in fact Corbusier has suggested is that the people living in flats should be given the choice of communal facilities and services both in their own buildings and in the town centre five minutes’ distant. We give them no such choice, but force them always to go out. Corbusier also makes it possible for those who live on the ground to shop or have a drink eight storeys up, whereas the flats we build are inaccessible to non-residents.

General view of the roof looking north. The cafeteria is in the foreground.

General view of the roof looking north. The cafeteria is in the foreground.

Two further points we should study in this exciting and beautiful building- first, the idea of a whole structure, a whole set of components, a whole series of spaces, designed on a system of dimensions all harmonically related, and all related to the human figure. Everyone who has seen the building testifies to the human and domestic quality of the building, contrasting with what Easton has called the heroic scale of the pilotis. To what extent the quality of the building derives from the use of such a geometrical system, or to what extent it is a result of the handling of such a system by a very great artist, we might discuss.

‘Everyone who has seen the building testifies to the human and domestic quality of the building.’

The other idea which seems most relevant to us is the development of the principle of the deep, narrow-frontage flat. The saving in external walling, maintenance cost and heating must be enormous, and if you want to know just how exciting and generous an interior of these proportions can be, I can only advise you to go to Marseilles.

Philip Powell

My immediate reaction is that this is a very lovely building-even the trial colours on the balconies. Some speakers have objected to these, and I would agree that anybody with pretensions to ‘good taste’ would not like them. I found their strength stimulating. (Especially, I remember a very wicked green.)

The poor craftsmanship in the handling of the concrete was very evident-as it happens, most effective in the case of the in-situ work and probably giving an intentionally rough effect. But I am not so sure I agree with Mr. Gooch that the roughness of the precast concrete work is intentionally contrived to avoid monotony.

Axonometric drawings of the Unite d’Habitation.

Axonometric drawings of the Unite d’Habitation.

Incidentally, I tried running round the semicircular end of the running-track. There is no banking at the moment, and the bend is so sharp that unless it is very steep indeed I visualize runners reaching parapet level at full speed and flying off the edge of the building.

But I have been asked to consider how far the Unite has an immediate application to our own housing problem. The principle of the deep slice plan is, in point of fact, traditional to the Victorian terrace-house and can be arranged, as in the Unite, to give good light in any flat. It would be particularly suitable over here for studios. However, I have some doubt about the advisability, in this country, of a bedroom overlooking a living-room except in studios. I would like to see double height flats with double height gardens as opposed to the minimum size box balconies, even if this meant (for financial reasons) the reduction in area of some of the rooms inside the flat. That, of course, means ‘away with the Housing Manual.’

Detail of the balconies and brise-soleil. It is suggested in the accompanying discussion that the rough finish of the pre-cast concrete units is a deliberate attempt to avoid monotony.

Detail of the balconies and brise-soleil. It is suggested in the accompanying discussion that the rough finish of the pre-cast concrete units is a deliberate attempt to avoid monotony.

Most people with families of any size prefer houses with gardens. But the possibility of twenty- or thirtystorey blocks, suggested by the Unite (yet reserved for smaller families) mixed with two- or three-storey compact house- with-garden development, seems to be the only rational approach to high-density planning.

View from the north-west of the building which was intended for the lower paid workers of Marseilles, and is due to be finished this summer. The overall plan dimensions are 460 ft. by 80 ft.

View from the north-west of the building which was intended for the lower paid workers of Marseilles, and is due to be finished this summer. The overall plan dimensions are 460 ft. by 80 ft.

Instead of alternating two- and three-storey houses or flats with five-, six- or even eleven-storey blocks of flats on, for instance, a thirty-acre site, we might divide the site in half, giving one half over to two- and three-storey garden terraces and the other half to, say, two twenty- or thirty-storey blocks of single, two and three room flats, giving, I feel, a happy contrast between the domestic, small-scale effect of the houses with their small enclosed open spaces and the blocks of fiats standing in wide public gardens. Of course the present system of subsidies might artificially make this development, with its increased number of houses, more expensive-in which case, scrap the present subsidies system. And the present by-laws would make a thirty-floor block of flats impossible-therefore scrap the by-laws too.

View below he overhang of the building, showing the patterns left by the rough formwork.

View below he overhang of the building, showing the patterns left by the rough formwork.

SUMMARY

The main observations and criticisms that arose during the subsequent general discussion are incorporated in the following summary of the symposium.

Town planning and social questions

It is a common mistake to criticize the Unite d’Habitation on the grounds that it is isolated by three miles from the true social life of Marseilles. But, as the contractor’s notice board proclaims, this is Unite d’Habitation No.1, and, as both Easton and Howell in particular pointed out, this single building must be considered only in relation to other similar and related buildings. In the absence of an available plan for Marseilles, Howell referred to the project for St. Die to stress the open ‘participating’ nature of each Unite as a counter to the objection made by Williams that the building was too self-contained and introvert (‘the housewife will have little need and less inclination ever to leave the building for days on end’). At the moment, it almost looks as if Le Corbusier had been sent out into the desert to make his experiment ‘in safety.’ The St. Die plan, however, shows five (ultimately eight) Unites disposed in relation to and ‘attracted’ by, a civic centre; and it is hard to suppose that what Easton calls an ‘agora-minded’ population would fail to take advantage of this. And in this context it should be stressed that the segregated level of pedestrian circulation from Unite to piazza provides that trafficless milieu that Venice proves to be so suitable to the Latin temperament and climate.

Plans of a typical flat. The overall dimensions of each flat is 12 ft. by 60 ft., lit at each of the narrow ends, which face east and west, with magnificient views over the mountains and the Mediterranean.

Plans of a typical flat. The overall dimensions of each flat is 12 ft. by 60 ft., lit at each of the narrow ends, which face east and west, with magnificient views over the mountains and the Mediterranean.

‘How much social research was carried out in the neighbourhood before the building was planned?’ Another line of criticism put forward by Cleeve Barr, Oliver Cox and Robin Rockel implied that Corbusier’s approach had been too arbitrary and abstract and too monumental. ‘He is at fault when he suggests that it is the task of architecture to create a new way of life.’ It is suggested that that is ‘imposing conditions’ on the people. And ‘it is interesting that in Moscow Corbusier is accused of Fascist tendencies.’ Philip Powell replied that by putting people in houses at all you are ‘imposing conditions’ on them; ‘these are simply different conditions which, in point of fact, provide better conditions and greater liberties than any other flat developments.’ And as a question of ‘social research,’ Corbusier claims that his concept is precisely the result of twenty-five years of such research.

Two views of the double-height living room.

Two views of the double-height living room.

It is unfair to suggest that the Unite is merely an essay in the monumental. In the first place, every speaker testified to the ‘humanity’ of the scale. Secondly, statistics suggest that, in the form of small flat development, it would have a very real application to social requirements. At first sight the rigid grid structure of the plan may suggest a lack of variety in the individual flats; in fact, apart from the combined accommodation of shops, hotel, communal rooms, health centre and recreation area, there are twenty-seven different types of fiat-plan. The richness of this variety combined with the remarkable sense of space achieved within a small area constitute a miracle of organization.

The flat-plan

Criticism of the vertical disposition of deep flats in relation to internal roads centres itself mainly on two issues. The central access corridors artificially lit and ventilated are open to criticism on the counts of climate, hygiene and potential hooliganism of children. The other issue was the difficulties of lighting and ventilating in the centre block caused by the deep section. Set against this the fact that light penetration in the Mediterranean climate is such that it is possible to read a newspaper by natural light in the centre of the blocks, that the lighting and services to the central utility area of the fiats were thoroughly approved by many speakers and have been officially inspected and approved by the local authority at Le Corbusier’s request (in order to quash rumours of uninhabitability); and finally, as Powell pointed out, that the ‘deep’ plan is no more than the traditional terrace-house wedge-plan with central unlit stair and rooms front and back of this.

‘The richness of this variety combined with the remarkable sense of space achieved within a small area constitute a miracle of organization.’

While the east-west ‘through’ orientation of the balconies may be made more desirable both by the intense heat of a southerly aspect and by the splendid views across to the mountains on one side and to the Mediterranean on the other, the actual size of the balconies is somewhat cramped.

Aesthetic

The most remarkable feature of the Unite is that in spite of its size it is completely devoid of any oppressive qualities. It looks human. This is true both of the overall mass (instinctive relation of number of floors and width, light ‘perched’ impression given by the pilotis) and of the subsidiary detail. The use of the Modular has not only ensured the absolute relation of parts to the whole but in so far as the starting-point of its geometrical progressions is that of a typical 6-foot human figure, these relations are not abstract but inherently human; ‘a whole structure, a whole set of components, a whole series of spaces designed on a system of dimensions all harmonically related.’ (Howell.)

A bas-relief of the ‘modulor’ man, on which is based Le Corbusier’s system of proportions. The method has been employed in the design of the Unite d’Habitation, down to the smallest detail.

A bas-relief of the ‘modulor’ man, on which is based Le Corbusier’s system of proportions. The method has been employed in the design of the Unite d’Habitation, down to the smallest detail.

It is particularly important that the real effect of this geometry as well as its practicability and lack of mumbo-jumbo should be stressed. In England lack of geometry during the last 100 years (Regency architecture still lived on the residue of eighteenth century geometry) has given licence to that wholesale reliance upon ‘intuition’ and ‘individual taste’ that contributes so much to the confusion of the day. The Unite is an outstanding vindication of the Modulor both on aesthetic grounds and on the practical coherence it gives to the ordering and relating of prefabricated elements.

Technical and structural

Comments upon site organization covered the various stages of the building during the last eighteen months. General verdict: ‘Medireval.’ Shuttering for the in-situ concrete is ‘quite crude, knocked together from rough timber.’ However, the answer to this may well be, as Max Gooch suggested, that the roughness of finish is an attempt to avoid monotony.

There is a very noticeable contrast between the use of comparatively flimsy materials within the flat itself and the almost indestructible nature of both structure and finish in the public and circulation areas.

One of the staircases leading to the first floor.

One of the staircases leading to the first floor.

Heating of corridors and flats is carried out by plenum; electrical heating elements are placed under windows past which air from the plenum is introduced. And in this respect too insulation is good owing to the great depth of each flat in relation to the short length of external wall.

Finally, the introduction of the Garchey system is nothing less than merciful in a locality where the normal method of refuse disposal is (as most of us who have spent a few nights in Marseilles have found to our cost) to throw it from the window into the street between midnight and 3.00 a.m.

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design