Madness in great ones must not unwatched go.

I was recently asked the impossible question of who my favorite (non-comedian) male and female studio era actors were. Acknowledging that any answer would at best be a half-truth, I finally resolved on Charles Laughton and Vivien Leigh (1913-67). Other than co-starring in Tim Whelan’s Sidewalks of London (1938), the pair have little if anything in common; I like them each for completely different reasons. Due to illness, early death, and her focus on the stage, Leigh’s cinematic output is frustratingly small, but what there is of it I love a great deal, especially the handful of well-known high water marks. She has intelligence, passion, vulnerability, intensity, and sex appeal. I love a “raw nerve” quality in an actor. Hers clearly bears some relationship to the mental illness that both plagued her and drove her, and it complicates things. Actors are as much works of art as they are artists. As objects of contemplation, they are only partially self-created; the rest comes from God.

Many commentators on Leigh’s career (including herself) decry the fact of her great beauty, claiming that it undermined or distracted from her skill as an actress. But speaking as a defender of the theatrical per se (with a special interest in the variety theatre) I am inclined to see no tension or contradiction there. In theatre and cinema, the aesthetic virtue counts as much as any other. It’s part of the package, at any rate. Personality and charm and a well-turned ankle are their own rationale and in any case do not imply a want of truth in performance. In the example of Vivien Leigh, they do so not at all. She won TWO Best Actress Oscars, and deserved them both.

Leigh (born Vivian Mary Hartley) was inspired to become an actress by the success of her slightly older school chum Maureen O’Sullivan. Leigh had spent her childhood in India, France and Italy as well as England. She studied at RADA, but quit before graduating in 1932 to marry a much older man, a barrister named Leigh Holman (from whom, presumably she took her pseudonymous professional surname). Five years later she became involved with the also married Laurence Olivier while working on the film Fire Over England (1937) and that altered the course of her life completely. The pair sought and attained the status of a great stage and screen couple, though unlike, say Lunt and Fontanne, they were doomed by Leigh’s erratic nature to split eventually. The pair were married from 1940 through 1960.

In 1937, Leigh starred in two Tyrone Guthrie productions: playing Ophelia to Olivier’s Hamlet and Titania to Ralph Richardson’s Bottom. Notable early films include the aformentioned Fire Over England and Sidewalks of London, as well as A Yank at Oxford (1938) with schoolfriend Maureen O’Sullivan, Lionel Barrymore, Edmund Gwenn, and future co-star and fireplace log Robert Taylor.

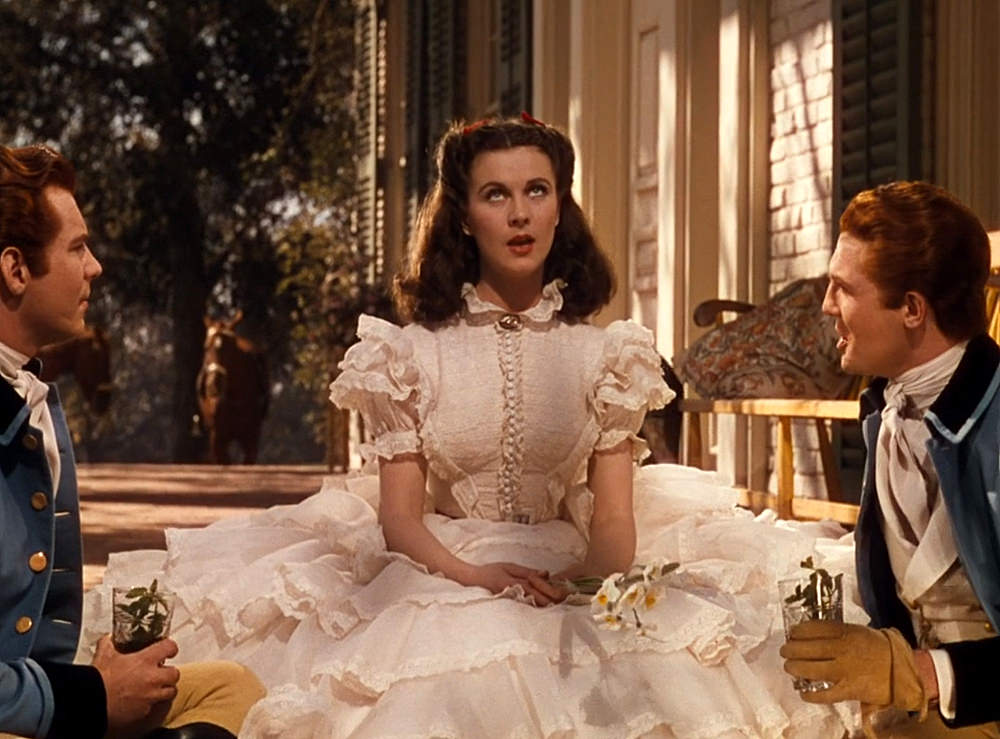

Not to be funny, but with actors it is frequently difficult to distinguish an artistic temperament from genuine mental illness. Leigh suffered from what we now call bipolar disorder (and by extension, so did the people around her). For years, her symptoms registered to her coworkers as her merely being “difficult”. Only later did they come to realize that much of her behavior was due to mental illness as opposed to merely being willful, stubborn, or egotistical. Depending on where she was on the cycle she could be violent, paranoid, terrified, depressed, insufferably upbeat, sexually ravenous, or unresponsive to the point of stupor. And she could swing from one mood to the other without warning on a dime. As it turns out this (combined with her talent and beauty) qualified her enormously for the part of Scarlet O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939). She famously won out over hundreds who wanted the role, and her fiery, mercurial portrayal really does seem to have brought Margaret Mitchell’s literary conception to three dimensional life. The lengthy historical epic might very well have been a bore without her at the center of it. And for one glorious moment, her fame even eclipsed her husband’s.

Leigh and Olivier proved a great stage couple; they were not destined to replicate that on the screen. They only co-starred in films a couple of times, in 21 Days (1940, based on a Galsworthy play), and That Hamilton Woman (1941). I’ve come to know the latter film quite well, because my wife is working on an illustrated book project about Lady Emma Hamilton. It’s nice to see them on screen together, although they both seem miscast in their roles (Lady Emma was zaftig and possessed a rustic accent, Lord Nelson was short-statured and macho). It would have been nice to see her opposite Olivier in Wuthering Heights (1939) but she had bigger fish to fry that year. (Interesting that Wyler cast fellow Anglo-Indian Merle Oberon in the role of Cathy. Seems kind of backwards — it’s Heathcliff that ought to be the one with South Asian roots!) With Leigh’s inarguable superstardom following GWTW you’d think she’d be a shoe-in (as she wanted) to star opposite her husband in Rebecca (1940) or Pride and Prejudice (1940), although granted she’d have been miscast in the former (she was actually much more like the deceased title character than the mousy heroine played by Joan Fontaine. How excellent would it have been, if she had! In a flashback!) Instead Olivier and Leigh next went on to star on stage in Romeo and Juliet in 1940 in several American cities, to mixed reviews. (Might have been an interesting film, but there had been one four years earlier starring GWTW co-star Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer!) It would also have been great to have seen her as Ophelia in Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet film since they had played those roles on stage together a decade earlier, but she was busy starring in Anna Karenina that year. And likewise his 1955 Richard III film (she had played Lady Anne onstage) but she was engaged in The Deep Blue Sea opposite Kenneth More at the time. I’d REALLY love to see the pair of them in a film of The Taming of the Shrew. (Liz and Dick pulled that showy stunt in 1967. Earlier, Taylor had replaced Leigh in Elephant Walk. There are many similarities between the two actresses. But, wow, how the sparks would fly in a performance by Vivien Leigh as Kate).

At any rate, Leigh was fated to make most of her films without Olivier. The next Leigh performance most movie buffs remember is the 1940 remake of Waterloo Bridge co-starring Robert Taylor. It’s fine, though I prefer the grittier pre-code original with Mae Clarke, and it didn’t exactly perpetuate the box office momentum established by her most famous role. But an uninterrupted growth trajectory was not to be her path. In 1942 she co-starred with Cyril Cusack in a West End production of Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma. In 1944 she came down with the tuberculosis that would eventually kill her. Its effects were no doubt exacerbated by the fact that she was a heavy chain smoker (which is often a concommitant of mental illness). She did rebound from this initial bout, though. In 1945, she co-starred with Claude Rains in the film version of Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, which, like Taylor’s later Cleopatra film, was a big budget box office bomb (though it’s a much better movie). The production was marred by an episode of manic depression triggered by a miscarriage. A few years later (1951) she would tour with Olivier in a double bill of Caesar and Cleopatra and Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

1945-46 Leigh played Sabina (the Tallulah Bankhead role) in the London production of Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth (1945-46). In 1948 and ’49 she embarked on a world tour with Olivier playing various classics. In 1949 she co-starred with Bonar Colleano in the London production of A Streetcar Named Desire. In 1951 she revived her role for the Hollywood film version opposite the original Stanley Kowalski, Marlon Brando (replacing the original American Blanche, Jessica Tandy). This of course landed her her second Oscar. And she was aptly cast as the pixilated, sex-starved dreamer. Much theatrical work with Olivier followed through the 1950s, although the pair began to grow apart. In 1953 she began an affair with Peter Finch, her co-star in Elephant Walk (a film from which she was fired due to a nervous breakdown). In 1958, her significant other became minor actor Jack Merivale, who stayed with her until the end of her life. She divorced Olivier in 1960.

In 1961, Leigh undertook her second Tennessee Williams role, as the title character in Jose Quintero’s screen adaptation of The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone opposite a young Warren Beatty in his second film role. I find her extremely moving in this film, as well as her last, Stanley Kramer’s 1965 adaptation of Katherine Ann Porter’s Ship of Fools, with Jose Ferrer, Elizabeth Ashley, Michael Dunn et al. Late theatre work included a 1961-62 tour in which she played Camille (foreshadowing!) among other roles, the 1963 Broadway musical Tovarich (for which she won a Tony), and a 1966 production of Chekhov’s Ivanov with John Gielgud. She had begun rehearsals for a production of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance with Michael Redgrave in 1967 when the TB recurred and took her at age 53 (although the ravages of mind and body made her look a decade or two older).

I wish the screen record were much larger. But, then, it is just like Scarlet O’Hara to leave a dainty foot-print.

You must be logged in to post a comment.