What is Bāguà?

Bāguà (Eight Trigrams or Diagrams) describes a set of eight symbols from traditional Chinese culture. They are part of an ancient framework to analyze the natural world based on a set of cosmic principles and express the core philosophical idea of dynamic balance (陰陽 yīn and yánɡ) and acceptance of change.

Tradition has it that the principle of Bāguà originated more than 4,000 years ago with the mythical Sage ruler Fuxi (伏羲). Of course, the historical accuracy of this claim is the subject of considerable debate among scholars. Eventually, these concepts were developed into one of the most important classical texts of Chinese culture, the Book of Changes (易經; Yìjīng, or I-Ching). Sometime around the Zhou Dynasty (1122 – 256 B.C.E.). Today, Bāguà remains a prominent part of Chinese culture, with the symbolic framework being used in fēng shuǐ (風水), divination, martial arts, and traditional Chinese Medicine.

Understanding these models of ancient Chinese philosophy is not necessary for becoming skilled in the practice of martial arts. Today far too much importance is placed on applying these models directly to martial arts practice. This is often done today to create the illusion of depth and mystery in the arts. The practices are already sufficiently deep and do not need these unnecessary layers to obscure the issue. However, learning the basics of these philosophies allows us to more deeply understand the people and cultures that produced the arts we practice.

The following is a good overview of the Eight Diagrams of Daoist Philosophy from The Dao of Taijiquan by Jou Tsung Hwa (page 118-125, published 1981). Selected sections edited by me.

The Eight Trigrams [八卦 Bāguà]

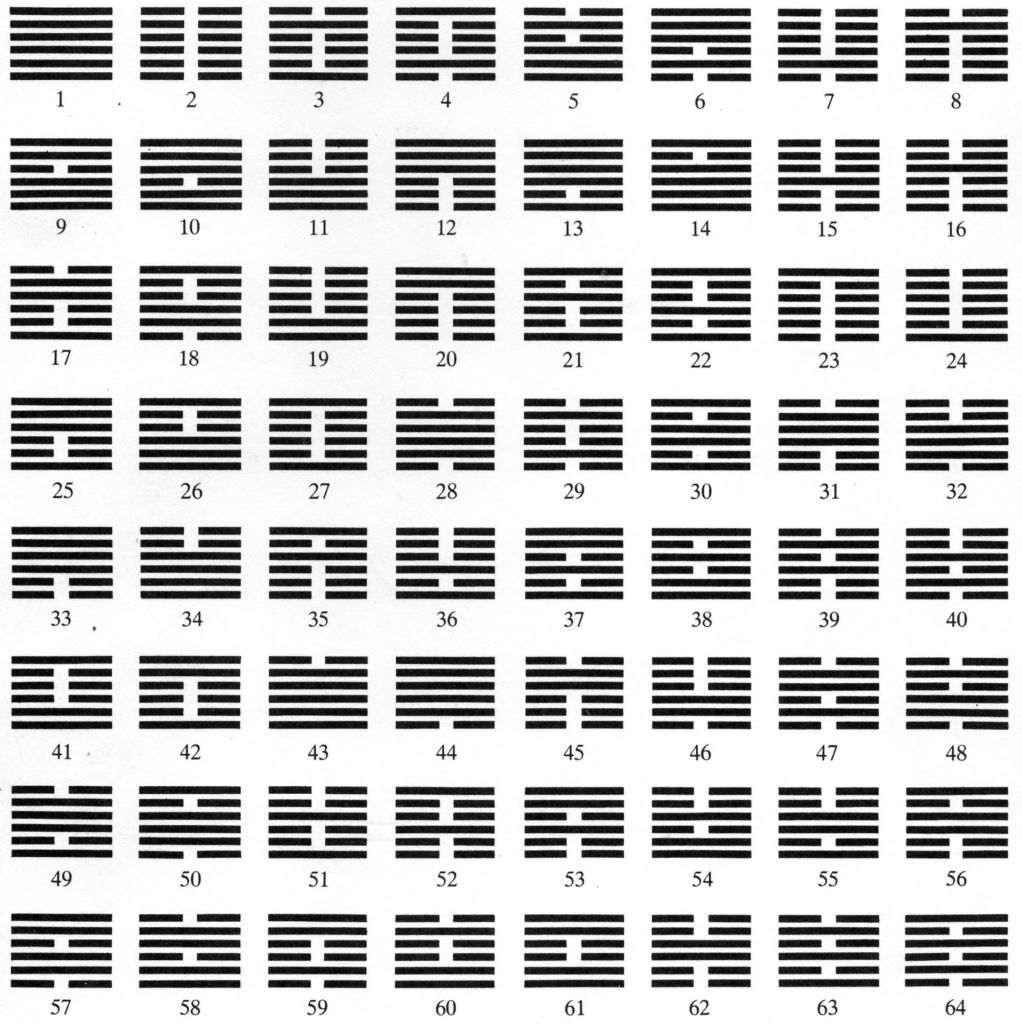

Just as in analytical geometry, in which a graphic method is used to explain equations, three layers of yin/yang symbols are used to represent each category in the taiji system [interplay of yin and yang]. These symbols are called the eight trigrams. They are used to classify all of the phenomena in the universe into eight categories and to analyze natural and social events with a logical method that searches for mutual relationships of their principles, phenomena and quantities. The taiji system can be widely applied and is not limited to the analysis of one particular object or event. Below is an ancient Chinese mnemonic for memorizing the eight trigrams:

Qián 乾 [☰] Three Continuous sanlian 三連

Kūn 坤 [☷] Six Broken liuduan 六斷

Zhèn 震 [☳] Upwards Cup yangbei 仰杯

Gèn 艮 [☶] Overturned Bowl fuwan 覆碗

Lí 離 [☲] Broken Middle zhongduan 中斷

Kǎn 坎 [☵] Full Middle zhongman 中满

Duì 兌 [☱] Deficient Top shangque 上缺

Xùn 巽 [☴] Broken Bottom xiaduan 下斷

These eight trigrams are the maximum number of figures that can be formed from two kinds of lines in groups of three. It was the Emperor Fuxi (伏羲, 2852-2738 BC), the first ruler in Chinese history, who applied the eight trigrams to the taiji diagram in order to demonstrate how yin and yang interact with each other. Fuxi’s circular arrangement of the eight trigrams is called the Fuxi or xiantian eight trigrams (先天八卦) [“before/pre-heaven arrangement”]. Xiantian means “the stage before the universe is created.”

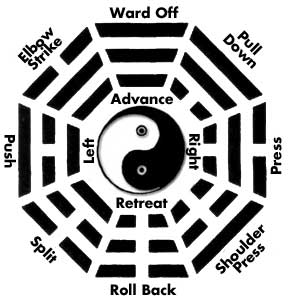

Along with the xiantian eight trigrams just described, there is another method of arrangement called the houtian eight trigrams (後天八卦) [“after/post heaven arrangement”]. According to legend, it was drawn around 1143 BC by Zhouwenwang (周文王) [King Wen of Zhou], the founder of the Zhou Dynasty at about 1143 BC and is based upon the Yijing [Book of Changes] which says:

“The ruler comes forth in zhen to start his creation. He completes everything in sun. He manifests things to see one another in li and causes them to serve each other in kun. He rejoices in dui and battles in qian. He is comforted and takes rest in kan and finishes his work in the year of gen.”

Starting from the east, the order of the houtian eight trigrams is in a clockwise sequence of zhen, sun, li, kun, dui, qian, kan and gen. This sequence is used to explain the principle of the notion of the universe and was the basis for the development of the Chinese calendar.

Formation of the Eight Trigrams

The Yijing tells of the formation of the eight trigrams or bagua (八卦). According to the Dazhuan (大篆):

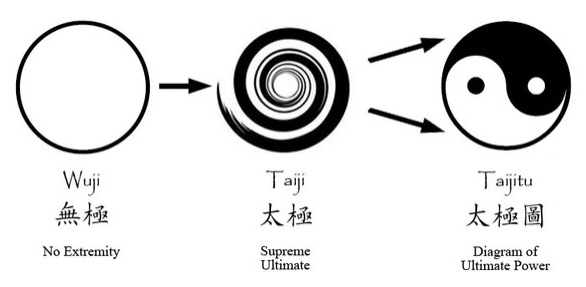

“In the system of the Yijing, there is the Grand Terminus or taiji, which generated the two forms of liangyi (兩儀) [“heaven and earth / yin and yang”]. Those two forms generated four symbols or sixiang (四象) [four divisions (of the twenty-eight constellations 二十八宿 of the sky into groups of seven “mansions”), namely: Azure Dragon 青龍, White Tiger 白虎, Vermilion Bird 朱雀, Black Tortoise 玄武]. Those four symbols divided further to generate the eight trigrams or bagua.”

The “Two”

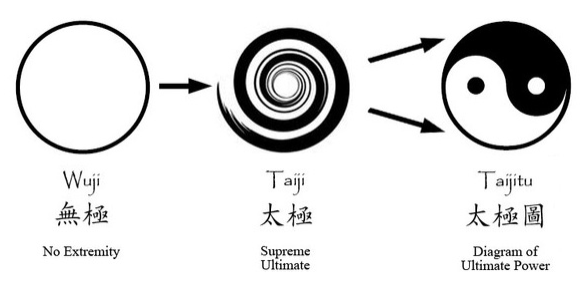

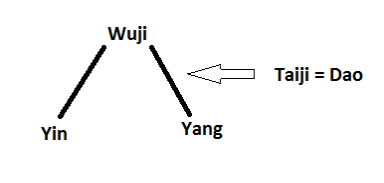

The taiji is the very first dot that emerges from the emptiness of wuji. It contains the moving power of both dynamic and static states and is the source of yin and yang. In the static state, yin and yang are combined to form a whole, but in a state of motion they separate, generating the two forms of liangyi [yin and yang].

Yang is often represented as a line segment or a small white circle. Yin is usually represented by two broken line segments or by a small black circle.

The properties of the two forms can be explained with the use of a straight directional line. Assuming that the point of origin is taiji, yin and yang indicate negative and positive direction. The next figure shows that yang can be represented by the positive direction, and yin by the negative direction.

The “Four”

The four symbols are the result of the combination of the two forms. Two yang symbols placed together, one above the other, are called the great yang (太陽). A yin sign placed above a yang sign is called the lesser yin (少陰). One yin sign placed above another is called the great yin (太陰). A yang sign placed above a yin sign is called the lesser yang (少陽).

The principle of the four symbols can be applied to every object or situation. Based upon its characteristics, principle and quantity, everything can be divided into four mutually related subdivisions…

The “Eight”

Diagrams on the development of the taiji system help to demonstrate how the taiji produced the two forms and the two forms produced the four symbols, which produced the eight trigrams. Three different methods are used to explain this process. One uses a circular form, another uses a rectangular form, and the third uses a tree diagram.

The Yijing…

The text of the Yijing was prepared before 1000 BC, sometime during the last days of the Shang Dynasty (商朝, 1766-1150 BC) and the beginning of the Zhou Dynasty (周朝, 1150-249 BC). It is one of the five classics (五經), edited by Confucius or Kongzi (孔子, 551-475 BC), who is reported to have wished he had fifty more years to study it. The Yijing has still not lost its enormous significance. Representatives from every segment of Chinese society – Confucianists and Daoists, learned literary scholars and street shamans, the official state cult and private individuals – have at one time or another consulted the Yijing.

The Yijing is not a religious book, but rather a book of profound wisdom that describes nature in terms of linear symbols. The method used in the Yijing analyzes every phenomenon into six stages. The symbols of yin and yang indicate the process of change. No matter how complex the event, the Yijing can trace the past, explain the present and predict the future. The Great Treatise or Dazhuan (大篆) describes the wide applicability of the Yijing:

“The use of the Yi is wide and great! If we speak of what is far, no limit can be set to it; if we speak of what is near, it is still and correct; if we speak of what is between heaven and earth, it embraces everything.”

From the above comments, we can see that the domain of the Yijing is as profound and all-encompassing as the universe. Not only does it explain the relationships among people in society, but it also can provide an explanation for the ever-changing phenomena of the natural world. Within the changing processes of the universe, the Yijing searches for the unchanging truth of the entire process of origin, development and outcome.

The Chinese character yi was created by combining symbols for the sun (日) and the moon (月). The sun symbol representing the yang force was placed on top of the moon symbol indicating the yin force. Based on the principles manifested in such natural phenomena, yi has three meanings: the easy, the changing, and the constant.

The book starts with the observation of natural events and daily life. These things are simple and easy to understand, e.g. a decayed willow sprouting flowers. Dazhuan, one of the oldest commentaries on the Yijing, describes the results of following the way of the easy and simple:

“Qian knows through the easy.

Kun does things simply.

What is easy is easy to know.

What is simple is simple to follow.

He who is easy to know makes friends.

He who is simple to follow attains good works.

He who possesses friends can endure forever.

He who performs good works can become great.”

The Yijing also describes the constant and the changing as follows: The wind changes the mirror image of a white cloud reflected in a stream, but the substance (i.e., the white cloud itself) is still unchanged. Although this change appears natural and simple, it is complicated in meaning. In order to understand the concept of change, you must first consider the opposite of change. You might think that the opposite of change is rest or standstill; however, these are but aspects of change. According to Chinese philosophy, the opposite of change is the growth of what ought to decrease, the downfall of what ought to rule. Change, then, is not an external principle that imprints itself upon phenomena; it is an inner tendency by which development naturally takes place. Although the phenomena of the universe are continually changing, underlying their changes is the principle of constancy. For example, if there is lightning, thunder must follow; after the moon is full, it must wane; if a decayed willow produces flowers, they will not last long.

The concepts in the Yijing are based on the taiji, which, as described earlier, develops into the two forms, which led to the four symbols, which precede the eight trigrams. From the eight trigrams, the 64 hexagrams are formed.

Every pair of trigrams has its mutual relationship and purpose; put together the two trigrams become a hexagram and form a logical whole with a unique meaning and developmental process.

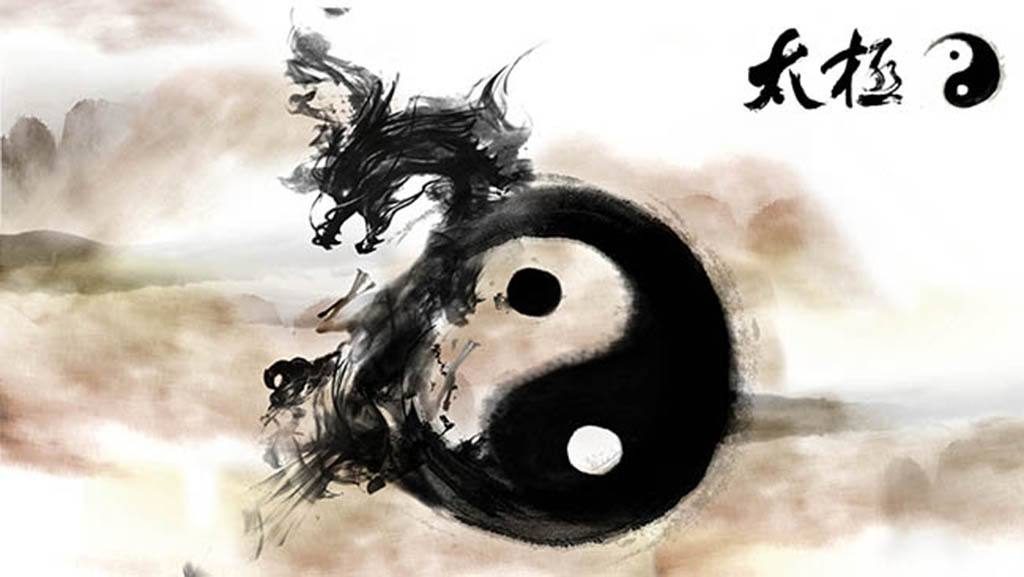

The Taiji Symbol & Taijiquan

The Taiji Symbol & Taijiquan

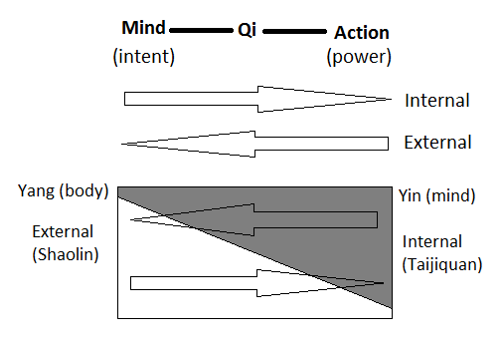

Internal style often teaches the student to develop the mind, then slowly move outward.

Internal style often teaches the student to develop the mind, then slowly move outward.

In the modern context, classical martial arts can be a very effective method for teaching a student the skills of self-defense, given that the practitioner trains in an appropriate and realistic manner. However, since martial art is no longer appropriate for warfare, there are other, even more impactful and compelling reasons to spend our finite time and energy cultivating these ancient practices and methodologies.

In the modern context, classical martial arts can be a very effective method for teaching a student the skills of self-defense, given that the practitioner trains in an appropriate and realistic manner. However, since martial art is no longer appropriate for warfare, there are other, even more impactful and compelling reasons to spend our finite time and energy cultivating these ancient practices and methodologies.

To start, I want to make clear that what follows is my own personal interpretation that has evolved over time from what I have been taught, my own research, practice and teaching. I do not use the term “correct” to imply there is only one way of understanding. Mine is not the only view, and there are certainly alternative opinions and understandings out there, even within the Yang style, much less the greater Taiji and internal martial arts communities in general. Additionally, I expect my understanding to continue to change, possibly dramatically, over time. I always encourage everyone to take what they are told, even from “authorities” and test it in light of their own experience and continuing study.

To start, I want to make clear that what follows is my own personal interpretation that has evolved over time from what I have been taught, my own research, practice and teaching. I do not use the term “correct” to imply there is only one way of understanding. Mine is not the only view, and there are certainly alternative opinions and understandings out there, even within the Yang style, much less the greater Taiji and internal martial arts communities in general. Additionally, I expect my understanding to continue to change, possibly dramatically, over time. I always encourage everyone to take what they are told, even from “authorities” and test it in light of their own experience and continuing study.

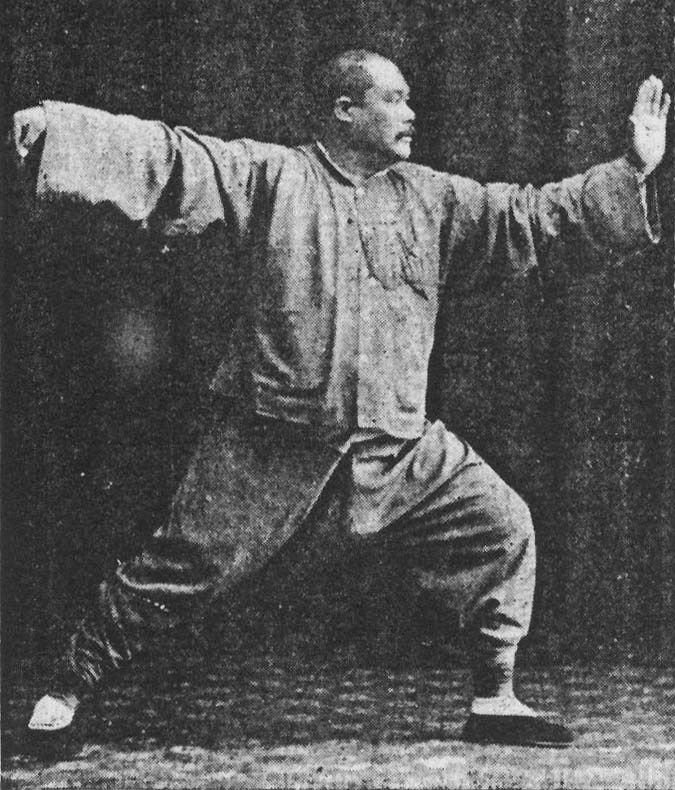

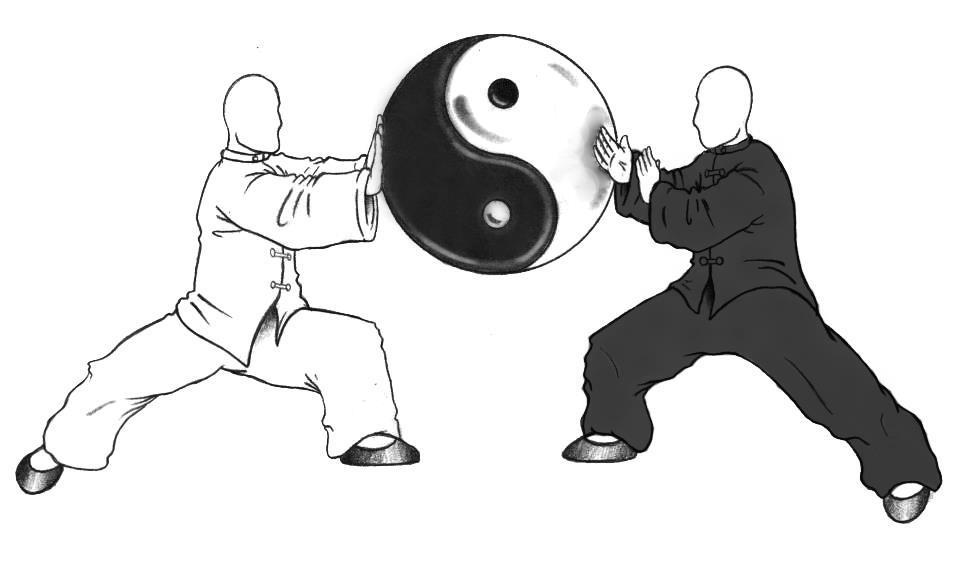

Together, the 10 Essentials and the 13 Kinetic Concepts can be seen as encompassing the totality of Taijiquan practice. The 10 principles govern the movements of Taijiquan. The practice of any of the composed forms of movement is limited. The movements are predetermined and finite. There is no way a form can include all the ways of movement that can be manifested through the principles of Taijiquan. To reach true expertise, the student will have to (at the appropriate point) transcend the limitations of the prescribed forms and drills, and enter the realm of spontaneous and intuitive movement.

Together, the 10 Essentials and the 13 Kinetic Concepts can be seen as encompassing the totality of Taijiquan practice. The 10 principles govern the movements of Taijiquan. The practice of any of the composed forms of movement is limited. The movements are predetermined and finite. There is no way a form can include all the ways of movement that can be manifested through the principles of Taijiquan. To reach true expertise, the student will have to (at the appropriate point) transcend the limitations of the prescribed forms and drills, and enter the realm of spontaneous and intuitive movement.  Although these principles are presented through the lens and framework of the classical teachings of the Yang school of Taijiquan, please do not make the mistake that they apply only to this practice. These principles are broad and general by intent. They do not discuss specific methods of attack and defense, but rather overarching principles that can be found in any high level practice of the martial arts. Any practitioner who endeavors to cultivate these principles, I believe, will experience great benefits in the practice of their specific methods.

Although these principles are presented through the lens and framework of the classical teachings of the Yang school of Taijiquan, please do not make the mistake that they apply only to this practice. These principles are broad and general by intent. They do not discuss specific methods of attack and defense, but rather overarching principles that can be found in any high level practice of the martial arts. Any practitioner who endeavors to cultivate these principles, I believe, will experience great benefits in the practice of their specific methods.

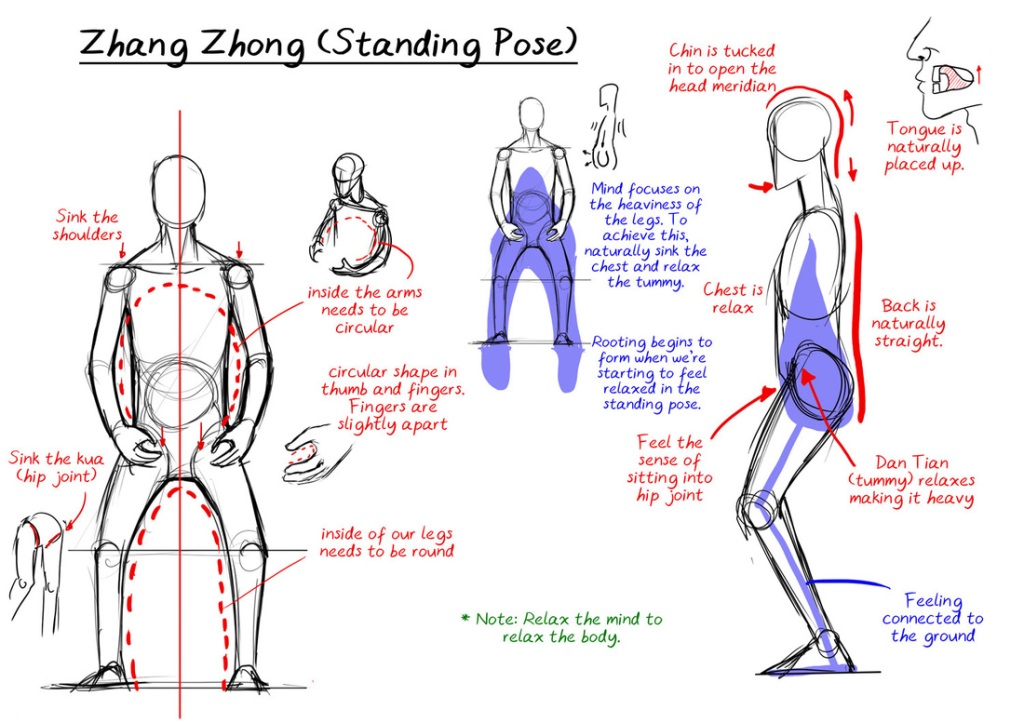

FUNDAMENTAL NINE STANCES

FUNDAMENTAL NINE STANCES