ArtSeen

Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth

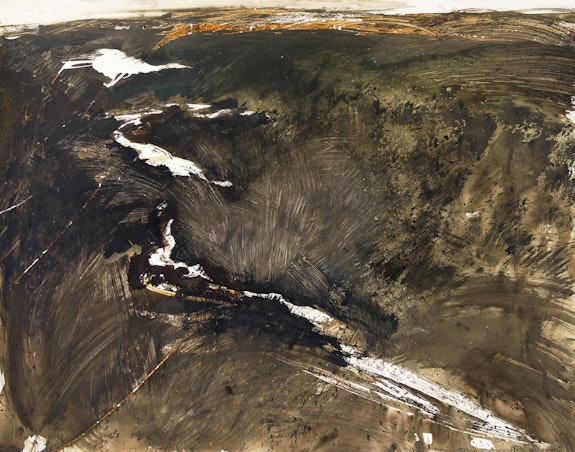

Andrew Wyeth, Untitled, 1948. Watercolor on paper, 21.5 x 29 5/8 inches. Collection of the Wyeth Foundation for American Art. © 2023 Wyeth Foundation for American Art/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

On View

Brandywine Museum Of ArtAbstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth

July 29, 2023–February 18, 2024

Chadds Ford, PA

Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth

April 6–September 8, 2024

Rockland, ME

Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth greets the viewer with a 1965 quotation by the artist: “My struggle is to preserve that abstract flash—like something you caught out of the corner of your eye.” Conceived and curated by Karen Baumgartner, the show follows Wyeth’s dedication to this “abstract flash” in sixty watercolors painted between 1939 and 1996. The show, drawn entirely from the trove of over seven thousand Wyeth paintings and drawings in the new Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection, is divided between the Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. Works Wyeth made in Pennsylvania are on display at the Brandywine and his Maine paintings will open at the Farnsworth in April. (My review will only cover the Pennsylvania side of the show.)

Pennsylvania and Maine defined the narrow compass of Wyeth’s seasonal migrations. He painted in Pennsylvania in the winter and spring, and in Maine in the summer and fall. Both sides of the show are reproduced in a beautiful catalogue (already sold out when I visited the exhibition in December) with essays by Karen Baumgartner, William L. Coleman, and Eric Aho, as well as a foreword by Thomas Padon. All the paintings in Abstract Flash have never been publicly exhibited, and Baumgartner’s astute selection steers clear of the classic views of the Kuerner family farm or the Wyeth home on the Brandywine River. When these locations do appear in paint, we see them from new angles, and the show consequently feels refreshingly unfamiliar.

Wyeth had a thing for painting out of doors. He created a studio every time he set down his palette and painting supplies—on a hillside, in a forest, or in his Jeep. These exteriors compliment the intense psychological portraits, his “interiors,” as it were, that he worked on concurrent with the outdoor paintings. Except for three barn interiors, Abstract Flash is all exteriors. Agnes Mongan, in her 1963 Dry Brush and Pencil Drawings, quotes a 1956 letter Wyeth wrote to close friends which makes his love of painting outside explicit: “This is my time of year and I spend all my time out in it. How I wish I could really get this down in paint.”

The earliest work in the Brandywine show, a 1946 watercolor of a barn and field, does “get this down in paint,” as the lower portion of the study is splattered with rain drops on the half-dry watercolor sheet. In an untitled watercolor from 1948, Wyeth paints a mass of soggy Brandywine River flood debris lodged in a low branch of a sycamore tree. An untitled 1961 painting of the Brandywine River depicts the river flooding banks near the site of the 1948 painting. Indeed, paintings of water—turbulent or still, muddy or crystalline—define the Chadds Ford side of the exhibition. In painting after painting, Wyeth returns to water as if his brushes were divining rods.

A near-abstract 1962 watercolor of a small pond depicts Wyeth’s subject with rapid, wavy black-and-umber brush strokes. The painting is one of scores of works featuring the narrow pond on the Kuerner farm. This work recalls an ink and watercolor drawing Mark Rothko made in the same year. Rothko’s small work is Wyeth-like, with its craggy, circling ink lines and blurry washes. Rothko worked as a watercolorist in the 1940s, and the aqueous transparency of these early works is everywhere in his classic oil paintings. The harmonic convergence of these two 1962 paintings underscores the aesthetics Wyeth shared with abstract artists of the 1950s and ’60s, an affinity that the catalogue essays highlight.

Another such point of contact is found in Wyeth’s well-known admiration of Franz Kline’s paintings. Kline, of course, was a Pennsylvanian, and perhaps in Kline’s thickets of paint Wyeth saw parallels to his own jagged topographies of their shared home state. More surprising was Wyeth’s friendship with color field painter Kenneth Noland. In 1962, Wyeth juried three of Noland’s abstract paintings into a Baltimore exhibition. In an excerpt from a 2009 interview reprinted in the catalogue, Wyeth recalled that most of the figurative paintings submitted to the show were “terrible but the abstract stuff was more interesting, the best work there.” From this early encounter Wyeth and Noland developed a long, if intermittent, friendship, and in the 2009 interview Wyeth expressed appreciation for Noland’s success.

In that same interview Wyeth noted Noland’s strong command of black, perhaps because he himself used copious amounts of black paint in his watercolors. Too much black has always been a no-no in polite watercolor practice. Wyeth never obeyed this rule and had no qualms about unloading tubes of lamp black on his paintings. For this reason (and others) Wyeth’s watercolors are iconoclastic, and I don’t think the medium has ever really recovered from his tornadic painting style.

Recently, Anne Classen Knutson suggested that Wyeth’s 1953 Snow Flurries memorialized the First World War. A 1951 untitled painting included at the Brandywine, perhaps a premonition of Snow Flurries, depicts a slim pathway of snow down a sloping hillside. This bleak painting forcefully recalls the soggy muck and damp of the Great War and seems a perfect demonstration of Knutson’s astute observation.

A 1958 view of a tree line at the edge of a field suggests images of other war zones, like photographs of the American Civil War. Minute leaves detach from a scrubby tree as the wind bends an adjacent sapling toward the center of the painting. When Wyeth raises the focus of his paintings above the horizon line, there are always hints of a breeze in bending boughs, blowing leaves, and gliding birds. Wyeth suffered pulmonary problems from childhood—could this inform the near constant suggestion of wind in his paintings?

Wyeth made his career on the strength of his early, tumultuous Maine watercolors. Spontaneous and rough, these works slowly gave way to the more precise tempera paintings that made Wyeth world famous. The value contrasts and paint handling in Abstract Flash retain the vital spirit of those early watercolors. The viewer tracks dramatic tonal changes from painting to painting, as perfectly articulated leaves and twigs flicker sharply against messy, abstract tangles of dark soil and water. The great strength of Abstract Flash is the confident, direct style of the watercolors. We see the moment of inspiration, the very flash.