Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Taanborsstrandloper |

| Arabic | دريجة برتقالية الصدر |

| Asturian | Mazaricu roxu |

| Basque | Txirri lepagorrizta |

| Bulgarian | Жълтогръд дъждосвирец |

| Catalan | territ rogenc |

| Chinese | 黃胸鷸 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 飾胸鷸 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 饰胸鹬 |

| Croatian | žutonogi žalar |

| Czech | jespák plavý |

| Danish | Prærieløber |

| Dutch | Blonde Ruiter |

| English | Buff-breasted Sandpiper |

| English (United States) | Buff-breasted Sandpiper |

| Faroese | Roðagrælingur |

| Finnish | tundravikla |

| French | Bécasseau roussâtre |

| French (France) | Bécasseau roussâtre |

| French (Guadeloupe) | Bécasseau rousset |

| Galician | Pilro canela |

| German | Grasläufer |

| Greek | Τρυγγίτης |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Bekasin savann |

| Hebrew | חופית זהובת-גחון |

| Hungarian | Cankópartfutó |

| Icelandic | Grastíta |

| Indonesian | Kedidi dada-abu |

| Italian | Piro piro fulvo |

| Japanese | コモンシギ |

| Korean | 누른도요 |

| Lithuanian | Gelsvakrūtis bėgikas |

| Malayalam | ഉണ്ടക്കണ്ണൻ മണലൂതി |

| Mongolian | Ухаа элсэг |

| Norwegian | rustsnipe |

| Polish | biegus płowy |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | maçarico-acanelado |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Pilrito-acanelado |

| Romanian | Fluierar cu piept gălbui |

| Russian | Желтозобик |

| Serbian | Žutogruda sprutka |

| Slovak | pobrežník trávový |

| Slovenian | Zlatar |

| Spanish | Correlimos Canelo |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Playerito Canela |

| Spanish (Chile) | Playero canela |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Praderito Pechianteado |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Zarapico piquicorto |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Playero de Pecho Crema |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Praderito Canelo |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Playero Pecho Ocre |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Playero Ocre |

| Spanish (Panama) | Playero Pechiacanelado |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Playerito canela |

| Spanish (Peru) | Playero Acanelado |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Playero Canelo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Correlimos canelo |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Playerito Canela |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Playerito Dorado |

| Swedish | prärielöpare |

| Turkish | Çayırkoşarı |

| Ukrainian | Жовтоволик |

Calidris subruficollis (Vieillot, 1819)

Definitions

- CALIDRIS

- calidris

- subruficollis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Buff-breasted Sandpiper Calidris subruficollis Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated November 10, 2017

Behavior

Locomotion

Walking, Hopping, Climbing, etc.

Gait described as high-stepping (3, 145); walks or runs between pecking attempts during feeding. Birds often stand on one foot to roost and occasionally hop on one foot (RBL).

Flight

Low, fast, and in tight flock formation (146, 144); rapid flight with many turns and zigzag movements; when near the ground turn frequently to reveal white underparts (description of birds arriving at decoys; Mackay 1892 in 7).

Swimming and Diving

Young or adults not reported to swim or dive.

Self-Maintenance

Preening, Head-Scratching, Stretching, Bathing, Anting, etc.

Species performs all but anting. Males preen extensively on breast and underwings after fighting with other males (see Agonistic Behavior). Extending wings common in males and females. Bathes at water’s edge by dipping head below water and raising to splash water over back. Often accompanies American Golden-Plovers when visiting water sources for bathing in Argentina (66, 67). Visits to wetlands for bathing most common in afternoons during migration (107).

Sleeping, Roosting, Sunbathing

Males on display territories roost (by placing bill and front of head under scapulars), especially during morning (01:00–05:00) and when no females present, for ≥ 30 min. In Argentina, records from the 1970s indicate that birds from broad area arrive in flocks of 5–20 (mean flock size = 16) to form monospecific roosts (600–1,000 birds in 500 x 300 m area) that form shortly before sundown and break up at sunrise. Spaced ≥ 20 cm apart, individuals roost in grass depressions or behind grass tufts (67). Such large roosts have not been recorded in 2000s. During spring migration, birds roost at night in agricultural fields and turf farms. No information on sunbathing.

Daily Time Budget

On breeding grounds, resident males are on lek territories throughout day and night, but frequently leave to forage or display elsewhere. Males at leks in northern Alaska spent 15–26% of their time soliciting females (i.e., wing and tail raises directed at females in the male territory), 7–11% attracting females (i.e. flutter-jumps and wing waves), 4% interacting with other males, and the remainder in maintenance activities including feeding and resting (147). See Breeding: Incubation for female attentiveness to nest. During spring migration in Nebraska, birds spent the majority of their time in agricultural fields where they foraged (51%), interacted with conspecifics (8%), rested (16%), performed maintenance behaviors such as preening and bathing (10%), and spent the remainder of their time walking or standing alert. Foraging duration and intensity was higher in the morning and evening, and lower in the afternoon (107). Behavior at wetlands was dominated by maintenance (27%) and resting (31%), with less time spent foraging (21%; 107).

Agonistic Behavior

Physical Interactions

Males defend breeding territories by aerial displays, ground chases and fights, and paired vertical flights (93, 1). In ground fights, males rush at each other with lowered heads, ruffled back feathers, and held-in wings. Birds peck each other on breast and back and hit each other with their feet; fights may last 10 min or more, interrupted by short breaks (RBL). Males in vertical flights fly up together at a 45° angle while fluttering wings and dangling feet, ascend slowly to 10–15 m before flying off in different directions (92). Birds that fly near or into male territories are aerial-chased by territorial owner; also ground-chase each other while holding up one or both wings (127, 67). The intensity of these interactions appears to peak in early June but then remains stable for the remainder of the breeding season (1). Males may chase females that leave nests for incubation breaks. Females mildly defend brood territories. Males and females defend foraging territories during migration and on overwintering grounds (127, 67).

Communicative Interactions

Threat displays. Males erect both wings at territory boundaries (often twice in succession) when alone and occasionally to each other. A similar double wing raise functions in courtship (see Sexual Behavior). Females also raise both wings and Flutter-jump (jump in the air and snap wings downward) when young are approached by humans. Displays are common during spring migration in North America (105, 142, 107) and occasionally on the overwintering grounds (A. Mäder and J. Almeida, personal communication).

Appeasement displays. Territorial neighbors (during migration and on breeding grounds) erect back feathers and depress tail while moving slowly near their mutual boundary; one or both may crouch, oriented parallel to one another and the boundary line for short time (2–3 min) before continuing agonistic encounter. One neighbor eventually flies or walks away (67, RBL).

Attraction displays. Males Flutter-jump (120) and wave one or both wings at conspecifics and heterospecifics (e.g., Pectoral Sandpiper, Semipalmated Sandpiper, Stilt Sandpiper [Calidris himantopus], American Golden-Plover, Black-bellied Plover [Pluvialis squatarola]; 92, 17, 147), landing in or flying over breeding territories. May display to humans. Single wing waves are common during spring migration where the light underwing is visible for long distances and may sometimes be directed towards flying conspecifics (106, JPM). Raised wings and tail solicit female to mating post where courtship begins (148, 147; see Sexual Behavior). Females also Flutter-jump and wave wings at chicks when separated; both behaviors may be used to reunite brood (RBL).

Spacing

Individual Distance

Roosting members maintain minimum of 20 cm on overwintering grounds (67).

Breeding Territoriality

Territories defended by males at leks range from 80–2,000 m2 (120) to over a hectare, though most are less than 200 m2 (93, 1). Leks are typically separated from each other by several km or more (93), with an average lek density of 1.7 leks/km2 observed during a 3-year study at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska (1). Distance to the nearest conspecific nest averaged 160.1 m ± 30.5 SE (n = 15) during single year in which species bred at Barrow, Alaska (46).

Overwintering Territoriality

Foraging territories are established gradually during the overwintering period; average size 0.04 ha (SE = 0.002, n = 29). Birds defend territories but flush in unison in loose flock in response to predators and then return to territories (67).

Interspecific Territoriality

May nest close to American Golden-Plover and Black-bellied Plover (149; D. McDonald, personal communication; RBL); these species occasionally chase females but do not elicit aggression.

Dominance Hierarchies

No direct evidence although a few males on each lek receive more female visits and copulations (93, 25). Although dominance is often a function of a male’s ability to acquire and maintain a lek territory in other lekking species (150), females copulated with males on and off leks and with males in peripheral and central territories. Also, males that are reproductively successful were just as likely to be disrupted by neighbors (93).

Sexual Behavior

Mating System

Mating system is variable within populations with the majority of males displaying at leks but others displaying solitarily (1, 147). Only North American shorebird to exhibit true lek behavior (35). Lekking behavior is extremely rare among shorebird species; besides the Buff-breasted Sandpiper, only Great Snipe (Gallinago media) and Ruffs form leks. Referred to as having an exploded-lek mating system because of large size of display territories (see Spacing: Breeding Territoriality, unlike that of the Ruff (1–2 m2; 151). Locations of most leks vary from year to year, with 69% of leks observed in northern Alaska from 1992–1994 being present in only one of three years (1). Within a season, the majority of leks were active for only 3 to 4 days. A small proportion of leks (ca 10%) were active in all three years (1) and these may represent traditional locations, which are typically located in dry, elevated areas along river bends (but not always).

Number and identity of males on leks change daily (even hourly). Leks at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, typically averaged 2.3 to 3.0 males with the most common lek size of 2 males. However, leks with 20 or more males have been observed (93, 1). Some males may remain at a single lek for most of a season while others move among multiple leks and may display several to many kilometers apart on successive days. At Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, 32 of the 56 males observed at leks remained for a day or less, while 9 males remained at a lek for more than 8 days (1).

Males also display in solitary locations away from leks. At Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, about 75% of males displayed at leks at a given time, while the remainder displayed solitarily at sites > 200 m from other males (1). This proportion remained relatively constant through the breeding season and was not correlated with the availability of fertile females. Some males display near active nests and direct displays to laying or incubating females (93, 1). Most females did not respond to males displaying near their nests but copulations did occur on a few occasions (93, 1) and these males were found to sire offspring occasionally (25). Previous suggestions that males may form short-term pair bonds and mate with females nesting inside their territories (152) or that males are waiting for renesting opportunities (93) were not supported by more in-depth study, though variation in mating system across the breeding range should be examined (1).

The variability in male mating tactics (e.g., solitary display, long-term territory holder at one lek, short-term territory holder at multiple leks) was not explained by morphology, behavior, or territory location (147). Males displaying solitarily and at leks were successful in attracting females, copulating, and siring offspring (147).

In contrast to other socially polygynous species where male reproductive success is skewed in favor a small number of males, paternity analyses indicate that male reproductive success has relatively low variance. Paternity of 47 families analyzed was distributed among at least 59 different males (25). Most males fathered between 1 and 4 offspring and only 4 males (6.8%) sired more than 4 young (25).

Recent tracking of males using satellite-transmitters and geolocators indicate they settled at several locations located hundreds of km apart during the breeding season (74, RBL); this suggest the species exhibits “nomadism”, a mating tactic in which males wander widely throughout the breeding range each year and opportunistically display and compate for mates at different sites within one breeding season (153). Further verification of mating behavior at these disparate sites is needed—the results of which may change perceptions of mating success.

Pair Bond

No pair bond established by lekking males. In one study (RBL, Prudhoe Bay, Alaska), females nested an average of 3.4 km ± 2.4 SD (n = 3) from leks where they were captured. Little opportunity for adults to re-pair in subsequent years because of low breeding site fidelity by either sex.

Courtship Displays and Mate Guarding

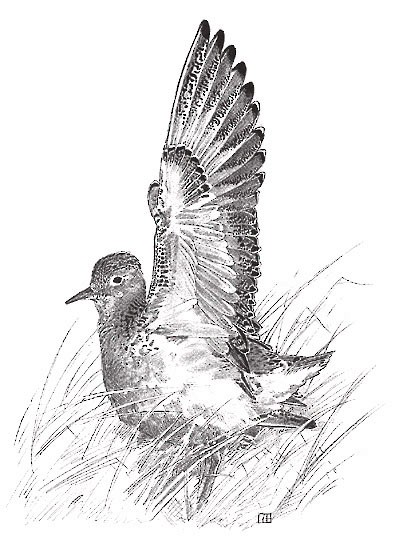

Compared to that of most sandpipers, both more complicated and different. Waving of one or both wings appears to be most important for display (Figure 5; see description in 127, 105, 148); underwings are satiny white with dark carpal patches that give illusion of flashing when wing waved (Figure 5). Males also Flutter-jump (see Threat Displays) and run along ground with erected wing and tail revealing white underside. Pruett-Jones (93) recognized 17 different courtship behaviors. Females that visit male territories are led to slight depressions called mating posts (usually one or two per territory) where precopulation behavior occurs. Females fly or walk on to male territories primarily in groups of 2–5 during the first few days of display and solitarily in later days. Some birds in these groups may be males (94, 147). Courtship behavior is also seen during spring migration (127, 105, 107), on overwintering grounds (67; see Social and Interspecific Behavior), and occasionally during fall migration (K. Karlson, personal communication).

Males regularly disrupt courtship behavior of other males by flying into a neighbor’s territory and scattering females. Alternatively, neighboring territorial males sneak onto a neighbor’s territory by walking through the vegetation with body pressed to the ground. Intruder waits near mating post until resident male has attracted females and then either rushes into disrupt courtship, or mimics female behavior so as to interrupt it when copulation seems imminent (93, 147). Pruett-Jones recorded that 32.2% of 236 visits were disrupted; 93) while Lanctot et al. (147) reported that 43% of 95 female visits were disrupted. The majority of females remained on the original male’s territory after disruption (67.6%), while the remainder either left the male’s territory or the lek altogether (17.1%), followed the disrupting male back to his territory (12.6%), or in a small number of cases copulated with the disrupting male after he inserted himself between the female and the territorial male or the territorial male had left to chase out a different intruder (2.7%; 147). These copulations involved the disrupting male mimicking female behavior (147).

Copulation; Pre- and Postcopulatory Displays

At the mating post, males begin precopulation display by opening wings in parabola shape several times. Females walk into this embrace and appear to inspect the white undersides of the wings (see Figure 6). Males often interrupt this display to fly up and around their territory boundary before returning to resume courtship. With wings outstretched, males finally tip their bill upward, stand on out-stretched toes, shake their entire body so that their wings move up and down vertically, and produce a series of ‘tick’ notes. Copulation is imminent when females open both wings and then turn so their back faces the male (105, 148, 25). Females seem to compete with one another to be closest to the male because only the nearest is mounted. Many times, however, the courtship is broken off when the male either flies up or the female(s) walk away from the male. Males mount females for 5–15 s and both preen after copulation. Copulations were only observed in 13% of female visits (based on observations of 95 visits over 2 year period, 147). As the number of females visiting leks decreases, males increasingly sneak on to neighboring male’s territories and occasionally participate in a homosexual mounting. This usually results when one of the approaching males goes to the backside of the resident male and mounts him. As many as 4 known males have been seen mounting each other (147; J. P. Myers and F. Pitelka, personal communications).

Extra-Pair Mating Behavior

Because no pair bond is formed, extra-pair terminology not pertinent. However, females mate with multiple males and continue to visit leks in middle of egg laying (25; R. Montgomerie, personal communication). Of 47 broods where paternity was analyzed, 19 (40%) included offspring fathered by more than one male and 5 and 14 of these included eggs sired by 3 and 2 distinct males, respectively (25). See Breeding: Eggs: Egg Laying for information on multiple-maternity.

Social and Interspecific Behavior

Degree of Sociality

Males aggregate together to display on breeding grounds (see above). During migration, large flocks occasionally found during day on bare or recently tilled corn and soybean fields (106, 102), and on turf farms (especially when irrigating during a hot dry period, RBL). Aggregations also observed during day on overwintering grounds (70). Large roosts form at night on the overwintering grounds (see Self-Maintenance, and Sleeping, Roosting, and Sunbathing). Groups of 10–50 birds congregate in small (0.01 ha) areas on overwintering grounds where they display toward one another (67). Similar behavior seen in Oklahoma (105), Nebraska, and Alberta (127). Group size in Nebraska averaged 3.7 ± 0.3 SD in 2004 and 4.7 ± 0.6 SD in 2005 (135), though multiple groups often occur in a single field so congregations of dozens to hundreds of birds are not uncommon (106). In South America, flock size averaged 4.8 ± 3.9 SD (range 1–17) in Paraguay (81). Average group size was 9 in Argentina (71). Surveys at overwintering sites detected average cluster size of 2.27 ± 0.22 SD in Argentina, 3.49 ± 0.40 SD in Brazil, and between 5.40 ± 0.75 SD (in 1999) and 5.96 ± 1.26 SD (in 2001) in Uruguay (70).

Play

No information.

Interactions with Members of Other Species

Species is often associated with American Golden-Plover during day and when roosting on overwintering grounds (66, 69, 117), and with Upland Sandpipers (112) and White-rumped Sandpipers (Calidris fuscicollis) during migration and on overwintering grounds (CLD). May nest near Black-bellied Plover (149) and American Golden-Plover (RBL), perhaps taking advantage of their warning calls for protection. American Golden-Plover also provides warning calls to roosting birds on overwintering grounds (RBL).

Predation

Kinds of Predators

Potential predators in Argentina include Cinereous Harrier (Circus cinereus), Long-winged Harrier (C. buffoni), Crested Caracara (Polyborus plancus), Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus), Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni), Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), Aplomado Falcon (F. femoralis), Barn Owl (Tyto alba), Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), canid (Dusicyon sp.), felid (Leopardus colocolo), and humans (67, 154). Peregrine Falcon killed one bird in dense flock of 100 and Merlin (Falco columbarius) found feeding on one during migration in Alberta (155, 156). Unsuccessful attacks on adults at lek by Parasitic Jaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus) and Long-tailed Jaeger (S. longicaudus; 93, RBL).

Potential predators during nesting and brood-rearing include arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes), short-tailed weasel (Mustela erminea), arctic ground squirrel (Citellus parryi), wolverine (Gulo luscus), Common Raven (Corvus corax), gulls (Larus spp.), Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus), Short-eared Owl, jaegers (Stercorarius spp.), Peregrine Falcon, and Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis).

Depredation resulted in loss of > 62% of nests in northern Alaska between 1992–1994 (25). Pruett-Jones (93) reported 61% nest depredation in same location from 1977–1980. Partial clutch loss from 2 of 11 nests from 1977–1980 (93) and from 4 of 24 nests in 1993; in latter case suspected predator was short-tailed weasel (RBL).

Manner of Predation

Arctic and red foxes take entire contents of nest; bowl often destroyed and urine and scat occasionally in or near nest. Short-tailed weasel suspected (based on mesh size of nest enclosures) of taking one egg at a time from nests until female finally abandons (RBL). Jaegers observed diving on adult males at leks (93, RBL). One flying juvenile was swooped on by Long-tailed Jaeger and hit to the ground, but juvenile escaped (RBL). Peregrine Falcons predominately use low surprise attack on foraging adults during migration (155).

Response to Predators

Territorial adults foraging on overwintering grounds flock in response to avian predators and then reestablish territories after predator leaves (some individuals remain crouched on ground). Flocking thought to lower predation risk but not to increase detection of predators (67). Similar flocking observed in Alberta; birds that flush in front of Peregrine Falcon drop to ground or water and take off in different direction (155). Migratory birds are extremely tame; when approached by humans, nearest members of flock either funnel around on the ground or fly up and land on other side of flock (108).

Breeding adults on leks crouch or make short jumps in response to swooping jaegers (RBL). Nesting females crane necks, turn heads, and exhibit alertness when avian predators are at a distance, but sit low and immobile when predators fly overhead or nearby (D. McDonald, personal communication). Response of incubating females to approaching humans varies from sneaking off nests when humans are 100–300 m away to flushing when humans < 1 m. Females commonly fly out of sight and then return and land 30–50 m from the nest, occasionally flying circles around nesting territories and giving quiet calls. During brood-rearing, females are more secretive and do not flush from the ground unless approached directly. When a female’s chicks are approached, she often flies within several meters, circles, and gives shrill, high calls. Females also exhibit typical Rodent Run behavior, spreading wing and tail feathers, ruffling back feathers, while crouched low to the ground. When pursued, females perform short Lead Away flights and run along the ground. Females never seen chasing away predators that approach nest or brood. If chicks captured, females occasionally raise both wings and Flutter-jump (see Courtship Displays). Newly hatched chicks respond to female’s alarm calls by freezing on ground, pre-fledglings run from approaching humans, and volant chicks walk in the open and only fly when approached (RBL).

Bathes at water’s edge by dipping head below water and raising to splash water over back.

In ground fights, males rush at each other with lowered heads, ruffled back feathers, and held-in wings. Birds peck each other on breast and back and hit each other with their feet.

Males defend breeding territories by aerial displays, ground chases and fights, and paired vertical flights. Males in vertical flights fly up together at a 45° angle while fluttering wings and dangling feet, ascend slowly to 10–15 m before flying off in different directions.

Wing-up Display of a Buff-breasted Sandpiper. Used mostly by males to attract females, but also by females to reunite their broods and by males toward intruding conspecifics and heterospecifics. The under-wings are satiny white with dark carpal patches, so when the wing is waved up and down in this display, it appears at a distance to flash on and off. Drawing by D. Otte from photo by J. P. Myers/VIREO.

Used mostly by males to attract females, but also by females to reunite their broods and by males toward intruding conspecifics and heterospecifics.

Males erect both wings at territory boundaries (often twice in succession) when alone and occasionally to each other. A similar double wing raise functions in courtship

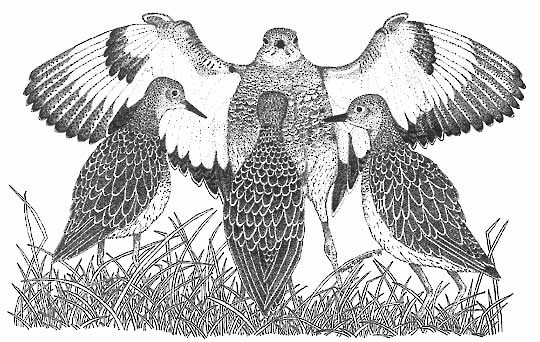

Buff-breasted Sandpipers (presumably males) direct double wing displays to each other on the breeding grounds, as well as during migration as shown here.

Part of the elaborate lek mating behavior of this species. With wings outstretched, such males tip their bill upward, stand on out-stretched toes, shake their entire body so that their wings move up and down vertically, and produce a series of ‘tick’ notes. Females move in close and appear to inspect the undersides of the male’s wings. Drawing by M. Whalen.

At the mating post, males begin precopulation display by opening wings in parabola shape several times. Females walk into this embrace and appear to inspect the white undersides of the wings.

Groups congregate in fields during migration where they display toward one another, using both single wing waves and double wing courtship displays.